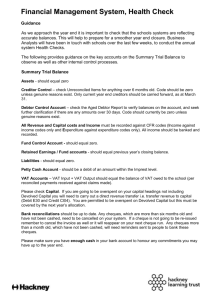

paper - CIRCABC

advertisement