introduction - Academic Commons

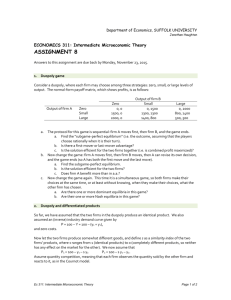

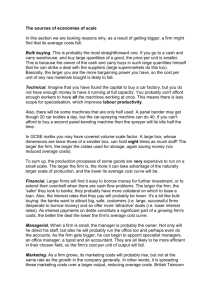

advertisement