Name: Jacob Archambault Phil 1000—Philosophy of Human Nature

advertisement

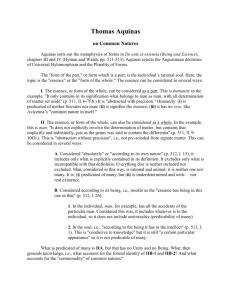

Name: Jacob Archambault Thomistic article analysis: Ia, q. 12, art. 10 Phil 1000—Philosophy of Human Nature Prof. Archambault Q.12, art. 10: Whether those who see God in his essence see all things they see in him together. I. None who sees God in his essence sees all things together (Modus Ponens) A. If what is seen in God is not many, then who sees God in his essence does not see all things in him together. B. What is seen in God is not many (Celarent) i. Nothing that is one is many1 ii. What is seen in God is one (Barbara) A. What is understood is one B. Those things seen in God are understood (Modus Ponens) 1. If God is seen by understanding, then what is seen in God is understood 2. God is seen by understanding II. No one who sees God sees all things in him together (Celarent) A. Nothing that understands and is affected successively sees all things in God together2 B. Whoever sees God understands and is affected successively (Modus ponens) i. If some seeing God (angels) understand and are affected successively, then all do ii. Some seeing God (i.e. angels) understand and are affected successively (Darii) A. Whoever is moved by understanding and affection is so successively B. Some who see God are moved by understanding and affection (Datisi) 1. Every spiritual creature is moved by understanding and affection (=Out) i. Every spiritual creature is moved by time ii. time = understanding and affection 2. spiritual creatures see God (=Out) i. an angel sees God ii. spiritual creature = angel Summary Aquinas states that what is seen in God (more specifically, in the Word of God) is seen as one (simul)3 and not successively. In support of this thesis, Aquinas does three things: first he pinpoints the cause of the lack of unity in the understanding of terrestrial humans; next, he shows that unified intuition is possible in a limited way in our present experience; third, he reminds his reader that the cause of the failure of intellectual unity is not present in the beatific vision, which, Aquinas thinks, entails the conclusion that what is seen in God is seen as at once. Before beginning, it is worth taking a minute to figure out exactly what is at stake in this question. The sed contra gives us a hint: Aquinas approvingly cites Augustine's statement that our thoughts in the afterlife will not be “going out and returning from some things to others.” In other words, what is at issue is whether, in the beatific vision, intellection is discursive. Aquinas presumes that this kind of understanding is imperfect. Given that imperfections are removed in the beatific vision, it is natural for him to hold that not it, but its contrary – unified understanding – is the norm for seeing 1 What is understood is one in that it is one species. But what is understood as one species may be a multitude in other respects: a house is one, but has several walls; a human is one, but precisely by being one human, is both rational and animal together. 2 According to Aquinas, angels understand both successively and simultaneously: the former occurs when they survey objects according to their natural powers; the latter, when they see these same objects as one in God. Hence, there is incompatibility between these two ways of seeing being in the same creature. 3 Throughout this exposition, I have refrained from translating simul as “simultaneously.” The structure of both the objections and Aquinas' respondeo make clear that what is at issue here is in fact a much thicker notion than that which we commonly associate with simultaneity, though this latter notion is certainly a part of the concept at hand. God. According to Aquinas, the cause of the multiplicity of our acts of intellection is the multiplicity of its objects. Our minds are directed both towards diverse images corresponding to different things: sometimes we think about beauty, sometimes about death, etc. But we can't think of things genuinely distinct as one any more than we can simultaneously focus our vision on two objects, or any more than a single lump of clay can simultaneously take on different shapes. But even in our earthly life we do, to a limited extent, view things which otherwise could be divergent as a unity: I hear a melody as such, and not merely as a discrete series of notes; when I look at a house, though I do not specifically attend to its various parts (e..g its roof and walls), I still see them as part of the more unifying notion house. In short, I understand things as one – a lecture, a window, the state – when I see it under one unifying aspect or form. By contrast, as long as I understand things under separate notions, I can only understand them successively. But in the beatific vision, as Aquinas argued in article 9, diverse objects are not understood by their proper forms, but in their higher unity in the being of God. Therefore, since diversity of images is a necessary condition for diversified intellection, its removal is sufficient to ensure that what is seen in God is seen in a unity – specifically, in the unity of the divine life.