Article on A-G fiat Part II

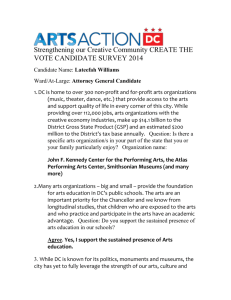

advertisement

The non – reviewability of the Attorney-General’s fiat. Part II : Review of the “role” of the Attorney-General Part Page # --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Round One : the Law Commission Report (1998) 02 Round Two : The Report of the House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Select Committee (2006) 04 Round Three : The Government’s Response (2007) 06 Round Four : The Government produces a Draft Bill (2008) 08 Round Five : The Committee’s Response to the Government’s Response (2008) 10 Round Six: The Government’s Response to the Committee’s Response. (2009) 13 Round Seven: The ‘Joint Committee’ & the Government’s Content Response Conclusions Appendix Chronology of Reports, Responses & Reviews Robert L MANSON for and on the half of Institute for Law, Accountability and Peace. (2008-9) 15 17 Page |2 Having now examined how the courts have hitherto approached the business of determining the status quo of, and to some extent also the justification or at least a rationale for, the nonreviewability of the Attorney-General’s prosecutorial procedural powers ; in Part II, I now propose to go on and examine how, those have fared whose job instead it is to review that position, with a view to recommending necessary changes in that status quo, in the interests of ‘justice, the rule of law, motherhood and apple pie’ as our transatlantic cousins might say. Round One : the Law Commission (1998) At the end of the 1990s, July 1998 to be precise, and therefore relatively shortly after the line of case law authorities considered above had been decided, the Law Commission in its turn decided to launch a full-blown Consultation, followed by a Report with conclusions and recommendations for amendment to the law on the specific topic of “Consents to Prosecutions” – this, of course, is the Law Commission Report 1998 to which I have already made reference.1 Of course, being a Report produced by the judiciary itself it’s not too surprising to find that there was barely any criticism of the state of the established case law either with respect to past controls over the institution and carrying on of so-called “private prosecutions”, or for that matter, more especially, with respect to the specific topic of the non-reviewability of the Attorney-General’s prosecutorial powers in particular. Of particular note perhaps, as illustrative of their position, were the following two recommendations as made by the Commission “Controlling the prosecution of offences which involve the national security or some international element 12 We recommend that prosecution of offences involving the national security or some international element should be restricted by a consent provision. Offences would be regarded as involving some “international element” if they (1) are related to the international obligations of the state; (2) involve measures that were introduced to combat international terrorism; (3) involve measures introducing response to international conflict; or (4) have a bearing on international relations. (paragraph 6.46)” “Offences involving the national security or some international element 16 We recommend that, where a consent is required, it should be that of the DPP except for those offences which require consent because they involve the national security or some international element, that consent should be given by a Law Officer. (paragraph 7.13)” Round Two : The Report of HoC Constitutional Affairs Select Committee In practice therefore, it was really left to Parliament to take up the cudgels of this issue as a matter of principle, as the only remaining fixed oversight body with an established role to do so. In the event, however, it took the aftermath of a further whole series of notorious “political controversies” which occurred during the appropriately named ‘naughties ‘, in which the role of the Attorney-General, as at least potentially giving rise to a reasonable presumption of interference with the administration of criminal justice, but in the true interests of political favour and the protection of political colleagues instead, had arisen before anything happened. 1 Law Commission Report (LC 255) Page |3 Of the three particular “controversies” mentioned below by the House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Select Committee, in its Fifth Report of Session 2006-07 – titled ”Constitutional Role of the Attorney General”2 - the reader will not now be surprised to discover that one of them specifically related to issues of so-called “national defence or security” whilst another was intimately concerned with our “relations with a foreign power”. As if just to prove how true to life were the episode plots of “Yes Minister” ! In the order in which the Committee chose to deal with them, these controversies were as follows: (a) The ‘Cash for Honours’ Investigation (b) Al-Yamamah Saudi Arms Deal / BAE bribes case (c) The 2003 Iraq Invasion and the publication of legal advice In short, and paraphrasing where necessary, the Committee set out the substance of the evidence they had heard on these matters, in sequence, and as follows: “The ‘Cash for Honours’ Investigation 38. In March 2006 it emerged that the Labour Party had been the recipient of a number of secret loans in the run up to the 2005 General Election and that some of the donors had been offered peerages. Angus MacNeil MP wrote to the Metropolitan Police asking them to investigate whether the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act 1925 which banned the sale of honours had been broken. Investigations have also focused on whether the Political Parties Elections and Referendums Act (PPERA) 2000 was breached and whether there had been conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. The case file was handed to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) on 20 April 2007, and on 4 June 2007 the CPS asked the police to “undertake further inquiries”. The possibility that senior Government colleagues or their aides and officials might be prosecuted has raised fundamental questions about a potential conflict of interest for the Attorney General, if faced with a decision of whether or not to pursue a prosecution. …. 41. When giving oral evidence to the Committee, Lord Goldsmith [A-G] gave the following commitment: “…if it is referred to me then my office will appoint independent leading counsel to advise, and, I make clear, in the event that there is not a prosecution then I will make public that advice. That will mean that the public will know openly, it will be transparent, what the reasons are and why” He confirmed that this would mean “the whole of the advice which relates to the decision not to prosecute”. Lord Goldsmith also said that he would be “perfectly content” to consult Opposition parties in an attempt to secure prior agreement on who he would consult and from whom he would seek advice. 42. We welcome Lord Goldsmith's commitment to publish the whole of the advice that relates to the decision not to prosecute should there be no prosecutions as a result of the Police’s inquiry into allegations of ‘cash for honours’. We also welcome his willingness to consult Opposition parties before deciding who should provide that 2 Published on 19 July 2007 by authority of the House of Commons Page |4 independent advice. We hope that the new Attorney General [Baroness Scotland] will honour these commitments. However, we are concerned that this does not address the fundamental conflict of interest that the new Attorney General may face in deciding whether or not to pursue a prosecution. “ Saudi/BAE case 43. The decision taken to drop a Serious Fraud Office investigation into allegations that Saudi officials were bribed to win an order for a British arms firm (BAe) has attracted significant levels of public scrutiny and controversy. As Attorney General, Lord Goldsmith was at the centre of this controversy which not only led to heavy public criticism64 but also to suggestions that the case could be subject to judicial review. Media speculation has focused on whether the Attorney General changed his mind in his decision of whether or not to prosecute as a direct result of political pressure from Downing Street. Lord Goldsmith himself acknowledged the controversial nature of this case, and stated that “this is the only case in the nearly six years I have been privileged to hold this office that there has been any sustained suggestion that a decision has been politically driven”. …. 45. In oral evidence to the Committee, Lord Goldsmith stressed to us that the decision (not to prosecute) “was taken by the Director of the Serious Fraud Office”, and that while he agreed with that decision, that his view was not based “quite on the same grounds” Lord Goldsmith also corrected any misunderstanding about his comments in respect of balancing the Rule of Law and the public interest. He said: “if anyone takes that as meaning that we … can set aside the Rule of Law for reasons of expediency or general interest, that is absolutely not the position”. He continued: “the Rule of Law does recognise that in all prosecutions the prosecutor will have to take account of two factors, the sufficiency of the evidence and whether the public interest is in favour of prosecuting or not”. In examining the public interest in this case, Lord Goldsmith acknowledged that he had consulted a “number of other Ministers” but maintained that “occasionally there are public interest considerations where it is legitimate to seek the views of other Ministers, not on whether there should be a prosecution but on what the public interest is”. Iraq and the publication of legal advice ? 47. Much of the discussion of the initial decision to invade Iraq was based on the advice given to the Government by Lord Goldsmith as Attorney General as to whether the invasion of Iraq was legal without a second resolution from the UN Security Council. The Government faced calls for the publication of that advice in full. On Tuesday 9 March 2004, Elfyn Llwyd MP tabled a motion for debate that “this House believes that all advice prepared by the Attorney General on the legality of the war in Iraq should be published in full”. While the motion was rejected in the House of Commons by 283 votes to 192, following continuing pressure and increasing media scrutiny, the Attorney General’s full advice on the legality of the war with Iraq was published on 10 Downing Street’s website on 28 April 2005. The document showed that the Attorney General’s advice of 7 March 2003 had examined possible doubts and arguments about the legality of the war. However, none of these concerns had appeared in the published advice of 17 March 2003.This only served to fuel speculation that Lord Goldsmith had changed his mind on the legality of going to war with Iraq in the face of direct political pressure from Downing Street. As a result Page |5 of this case there has been recent debate about whether the Attorney General’s legal advice to Government should be published as a matter of course. …. 49. However, there was little support for this position amongst our witnesses. Lord Goldsmith told the Committee that “the Attorney General is, and must remain, an adviser to the Government and not to Parliament. He or she cannot serve these two clients simultaneously without running into impossible problems of confidentiality and conflict of interest” ….” Having then heard this evidence, and considered these matters within a far wider historical context of the constitutional conventions and practices underpinning the office of the Attorney-General and its wider role and functions, the Committee then came to the following uncompromising conclusions: “ 54. Recent controversial issues including the ‘cash for honours’ investigation, the decision not to prosecute in the BAE Systems case and allegations of political pressure to amend legal advice on the war in Iraq, have compromised or appeared to compromise the position of the Attorney General. The perceptions of a lack of independence and of political bias have risked an erosion of public confidence in the office. 55. We agree that there are inherent tensions in the role of the Attorney General and that this is not a new situation. However, it is time that these issues were addressed. The tensions which have been highlighted by these three controversial cases, alongside the institutional problems identified earlier, point to the need for the reform of the role and responsibilities of the Attorney General. …. 83. The present situation where the Attorney General has both ministerial functions and is responsible for making decisions with regard to prosecutions results in a potential conflict of interest. While separating these two functions would not make difficult decisions any easier to make, it would remove the potential for the allegations of lack of independence and political impropriety. We recommend that the Government separate the policy functions and the prosecutorial functions of the Attorney General. The ‘ministerial’ functions would be more appropriately carried out by a minister within the new Ministry of Justice. This would also allow the Attorney General to be a truly independent superintendent of the prosecution services, responsible for deciding on prosecutions and exercising a propriety and public interest role, except in those cases where he or she was instructed by ministers, in a process which would have to be transparent, that on national security or public interest grounds a prosecution should not proceed. …. Conclusions and recommendations 6. The Attorney General’s responsibility for prosecutions has emerged as one of the most problematic aspects of his or her role. Allegations of political bias, whether justified or not, are almost inevitable given the Attorney General’s seemingly contradictory positions as an independent head of prosecutions, his or her status as a party political Prime Ministerial appointment, and his or her political role in the formulation and delivery of criminal justice policy. This situation is not sustainable.“ (Emphasis added) Page |6 Round Three : The Government’s Response (2007) As any half-decent administrative batsmen knows, when defending a sticky wicket, it is always a good idea to be in the position to answer critics with the stock riposte “the matter is currently under active consideration”. During the course of the Committees enquiry, and shortly prior to the publication of its Report, the Government produced a Green Paper entitled “the Governance of Britain” (published 3 July 2007)3. It said the following with regard to the role of the Attorney-General, as follows: “54. The Government is fully committed to enhancing public confidence and trust in the office of Attorney General and is keen to encourage public debate on how best to ensure this and will listen to the views of all those with an interest. We will therefore publish a consultation document before the summer recess which considers possible ways of alleviating these conflicts (or the appearance of them) and invites comments. The Government looks forward in particular to the report of the Constitutional Affairs Select Committee of the House of Commons, and will study the Committee’s report carefully.” In due course the “Consultative Document” was produced in the late summer of 2007 under the title “A Consultation on the Role of the Attorney General” with a notably user-friendly introduction by the new and first ever lady Attorney-General, Baroness Scotland of Asthal. Before moving on consider in detail the then Government’s understandings on the present issues it is, I believe, somewhat revelatory to pause for a moment and consider what this paper had to say on the especially controversial issue of its understanding as to the Attorney-General’s power to “direct“ the DPP in relation to the exercise of his powers in any particular individual case of prosecution. At the following point in its introduction the paper says as follows: “1.23 The legislation does not expressly provide for the Attorney General’s power of superintendence to include a power to direct the prosecuting authorities to prosecute (or not to prosecute) a particular case, or to take (or not to take) any other form of action. On this, the Glidewell report 4commented as follows: “The effect of the Attorney General’s power of superintendence of the DPP, established by the practice which has been followed both before and after 1985, appears to us to be as follows: …. 3 “the Governance of Britain” (a Green Paper) Ministry of Justice - 3 July 2007 Cm 7170 4 “A Review of the work of the Crown Prosecution Service” ; carried out by Lord justice Glidewell in 1998 (Command 3960) Page |7 ii) Although there may be some doubt whether in theory the Attorney General does have the ultimate power to direct the DPP to prosecute or not to prosecute in a particular case, it seems that in practice all holders of both offices have accepted that the Attorney General’s power of superintendence of the DPP is such that, in the event of a stark disagreement, the Attorney General’s view would prevail. However, we find it difficult to believe that, in such a situation, an accommodation between the differing views would not be reached without a formal direction.” 1.24 In practice the point has never been settled definitively and successive Attorneys General have not sought to give formal directions to the prosecuting authorities.” The reader is, of course, now in a position to compare this verbiage both with (a) the quite uncompromising position as set out by Viscount Dilhorne - nee Sir Reginald ManninghamBuller PC, himself a former Attorney-General (1954-62) in his opinion in Gouriet’s case (as above) in which he maintained quite unabashedly, albeit prior to the introduction of the PoA 1985, that the A-G can both direct the institution of, and ban the continuation of, a criminal prosecution by the DPP – and in either case he is immune to “control and supervision by the courts” – and for that matter also compare it subsequently with (b) the new “Protocol between the Attorney-General and the Prosecuting Departments” as introduced in pretty quick order by the learned Baroness, just two years later (in July 2009) and in Paragraph 4(b)1 of which we now recall the new Attorney-General formally sets out her power to specifically so “direct” the DPP, at least in cases where ‘in her view’ issues of “national defence and security” are involved. My only observation being, I would suggest perhaps inevitably, that where one holds such great powers in the sure and certain knowledge that one’s exercise thereof can never be even examined , let alone judged, by others, then the overwhelming temptation, when asked how extensive those powers are, is obviously ‘to make it up as you go along’ ! Before then going on to ask the ‘consultative question’ as to what contributors thought ought to be the proper constitutional role of the A-G in relation to the conduct of criminal prosecutions, the Government set out its own understandings as follows: “Legitimate role of Government in relation to criminal prosecutions 3.16 It is important to recognise that “the public interest” is not just a legal concept, completely detached from wider policy considerations. On highly sensitive cases, for example those involving national security, the Government has an obligation to decide where the public interest lies. Completely removing any relationship between the Government and the prosecutors on individual prosecution decisions would prevent the Government from providing any input on national security issues (or any other public interest issues), by that direct route. 3.17 Currently prosecutions are conducted under the superintendence of an Attorney General who is a member of the Government and can be expected to be sensitive to the wider public interest considerations, and is in a position to consult Ministerial colleagues about them (through the well-established Page |8 mechanism of a “Shawcross” exercise22) and then to be held accountable by Parliament. 3.18 The legitimacy of the involvement of a Minister of the Crown in decisions where national security or an international element is at issue was recognised by the Law Commission as part of its Report on Consents to Prosecution. “ Round Four : The Government produces a Draft Bill ! (2008) In response to the formal Consultation process, the Government produced an Analysis of Consultation document the following year (25 March 2008). At the same time, and following the theory that once you’ve started on a strategy of obfuscation the best policy is always to double-down, it also produced a further White Paper this time titled “The Governance of Britain: Constitutional Renewal” and this time together with a so-called draft Bill, the “Constitutional Renewal Bill”, accompanied by Explanatory Notes. The “Draft Bill procedure” being a relatively new innovation in the Parliamentary “long grass” landscape, whereby a specialist pre-legislative joint review Committee of both Houses of Parliament, subject to fresh appointments determined principally by the will of the Governing Party, is set up to examine and report on the draft Bill in detail, even before its first reading on the floor. However, in the interests of not leaving any tree left standing, the Government also produced its own further dedicated Response to the Constitutional Affairs Committee’s Report. 5 On the topic of reducing the number of instances whereby the specific consent of the Attorney-General is required by statute to institute a prosecution, it had this to say: “21. The Government proposes to legislate to provide that the Attorney General should cease to have the statutory function of giving consent to prosecutions except in relation to a small category of offences which are considered to have a high policy/public interest element (for example, prosecutions under the key provisions of the Official Secrets Acts). In other cases the requirement for consent should transfer to the Director of Public Prosecutions (or in certain cases the Director of another prosecuting authority) or, in relation to certain offences, be removed altogether.” Although, on the more controversial topic of the A-G’s powers to direct the DPP in relation to the termination of any particular criminal prosecution, including in the case of individual private prosecution, it had this to say: “41. The Government has also accepted that there is merit in clarifying and limiting the role of the Attorney in relation to individual criminal cases. This is appropriate both to ensure that decisions in individual cases are taken independently, and to promote public confidence in the operation of the criminal justice system. 42. This is why we have proposed legislation which provides that the Attorney may not give a direction in relation to an individual case. 43. A very limited exception is to be made in cases giving rise to a risk to national 5 The Government’s response to the Constitutional Affairs Select Committee Report on the Constitutional Role of the Attorney General - April 2008 - Cm 7355 Page |9 security. As the Committee recognised, the Government does have a legitimate role in assessing whether a prosecution which poses a serious threat to national security should proceed. The Government takes the view that in such cases, the Attorney should be able to have the final say as to whether such a prosecution proceeds. But in such a case, it should be made clear who has made that decision – and who should be held accountable for it. This reflects the views of a number of respondents (including the Criminal Bar Association), albeit other respondents took a different view. 44. The Government notes that neither the Committee nor the vast majority of respondents considered that any Attorney General had in recent years actually exercised his or her functions in an improper or partisan manner. The Government agrees with those respondents who took the view that “mistaken perception is a weak foundation on which to base reform.” (Lord Lloyd of Berwick)” (emphasis by way of underlining added) This is a classic example of how one needs to be especially wary when one’s government starts to legislate in a specially appointed Committee on a draft only Bill. When the Draft Bill was introduced in the Commons (March 2008), Clause 12 setting out the powers of the Attorney-General in relation to this matter, arguably appeared consistent with the above quoted intentions. Then again, in or about the same time (March 2008 – published 18 April 2008), the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution6 produced its own Report on “Reform of the Office of the Attorney-General”. However, presumably in keeping with its own sense of its own role in the constitutional conventional construction, as a reviewing chamber alone, whilst it doubtless spent a small fortune of public money in taking formal evidence (both written and orally), and in then reporting on its own ‘review’ and ‘analysis’ of the competing arguments raised, it actually concluded or recommended nothing whatever. Instead, it described its function in producing the Report as, “We trust that this Report will prove useful as a ‘handbook’ to guide members of the House through the continuing debate on the role of the Attorney.” Worryingly, however, a year later by the time the Bill actually came up for its first reading in their Lordships’ House (March 2009) Clause 12, as above, had then become Clause 15 instead, and its language had changed notably dramatically, as follows: Cl.15 titled “Duty to intervene on ministerial certificate concerning national security” began, as follows: “ (1) This section applies where the Attorney General receives a certificate signed by a Minister of the Crown stating that the Minister is satisfied that— (a) the carrying out of an investigation of specified matters, or (b) the institution or continuation of proceedings for a specified offence, is likely to prejudice national security. 6 The House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution Seventh Report of Session 2007–08, Titled "Reform of the Office of Attorney General" Published in April 2008 - HL Paper 93 P a g e | 10 (2) The Attorney General must give such of the following directions as appear to the Attorney General to be necessary for the purpose of avoiding the prejudice to national security referred to in the certificate— (a) a direction to the Director of the Serious Fraud Office that no investigation of specified matters is to take place in England and Wales; (b) a direction to any prosecutor, in relation to an investigation of specified matters, that no proceedings for an offence are to be instituted in England and Wales in respect of those matters; (c) a direction to any prosecutor that proceedings for a specified offence which are being conducted in England and Wales against a specified person are not to be continued.” (emphasis by way of underlining added) “Specified offence” by the way means no more than an offence “specified” by the Minister in his Certificate7. The idea that this statutory language gives the Attorney-General the “final say”, as to whether any individual prosecution proceeds or is quashed instead is a manifest nonsense. Under this language the A-G is reduced to a mere functionary, whose purpose is simply to determine under which of the three broad categories of intervention as listed, the stated will of the Minister to avoid his proclaimed apprehension that such a prosecution is “likely to prejudice national security”, need to be invoked in order to pander to that apprehension. It is entirely for the Minister’s discretion, and his alone, as to whether any such genuine “prejudice to national security” actually exists or not, and thus whether the prosecution concerned proceeds or not. The real effect is merely that the Minister concerned, putatively the Secretary of State for Defence, also now gets to hide behind the Attorney-General’s ‘cloak of invisibility’, when it comes to the judicial review powers of the judiciary. Consequently, the effect of this provision, were it to have become law, would have been to actually completely and utterly “politicise” the whole process of terminating criminal prosecutions of this character , in place of the reverse, whenever an especially un-welcomed prospective prosecution was in contemplation as determined by the view of the Government Minister of the day alone. Round Five : The Committee’s Response to the Government’s Response (2008) First of all it’s worth noting in passing, the work of the House of Commons Public Affairs Select Committee, which took on the role of analysing and reviewing much of the Government’s proposals in the Draft Bill8, on wider constitutional and public confidence issues, but which then deliberately avoided specific comment on the Role of the Office of the Attorney-General, as well ; leaving this latter instead to the newly created House of 7 8 As to which see @ Cl.15(4) in the Bill (HL). HoC Public Administration Select Committee, Tenth Report of Session 2007-08, Constitutional Renewal: Draft Bill and White Paper, HC 499 - Published 4 June 2008 P a g e | 11 Commons Justice Committee – and which took on the role of, and effectively replaced, the former Constitutional Affairs Select Committee. This Committee was determined not to be ’side-lined’ by the creation of the new Joint Committee on the Draft Bill, but instead determined to go ahead and create its own Report on the Draft Bill and associated publications9 at least as they applied in relation to the role of the Attorney-General, and in addition to the prospective product of the specific Joint Committee as well. Indeed, the Justice Committee specifically took the opportunity to highlight and concur with the recent conclusions of the Liaison Committee, in openly criticising the Government’s view that, when deciding between review of a Draft Bill by existing Select Committees or the creation of a specific Joint Committee on the new Draft Bill instead, the assumption was not that “the Government should decide the means by which Draft Bills are scrutinised.”10 The Report begins with a specific recollection of the thrust of the Report of the Committee’s predecessor, as follows: “26. Our predecessor Committee's Report on the Constitutional Role of the Attorney General recommended separation of the ministerial functions from the responsibility for prosecutions. It said that depoliticising the prosecution role should be one of the central purposes of reform, not least in order to restore public confidence in the role of Attorney-General.” The new Justice Committee heard principally from two of the country’s leading administrative and constitutional law academics & practitioners 11 who took predictably competing views on the core issue of the potential for “politicisation” of the quasi-judicial roles of the AttorneyGeneral. The Committee appears to have favoured the pro-reform position posited by Prof Jowell, as follows: “ 51. Professor Jowell in his evidence argued that sections 12 and 13 of the Draft Bill (powers to halt prosecutions or investigations) “fly in the face of the fundamental constitutional principles of the rule of law and separation of powers”. He also points out that the provision provides a very broad discretion to the Attorney General (who will act “if satisfied” of the need to do so). Clause 13 (5) (a) seeks to prevent any possibility of judicial review by providing that a certificate signed by a Minister of the Crown certifying that the Attorney’s direction was “necessary for that purpose” (i.e. to safeguard national security) shall be “final and conclusive”. Taken together, these powers allow the Attorney General to make a decision which is excluded from examination by the courts. Clause 13 (5) (a) is effectively an “ouster” clause, which in practical terms sets aside the jurisdiction of the courts. Professor Jowell says: “These provisions brazenly seek to evade … recent developments of constitutional principle.” We see no case for the inclusion of the ouster clause.” 9 House of Commons : Justice Committee Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill (provisions relating to the Attorney General) Fourth Report of Session 2007–08 Report, printed 17 June 2008, published 24 June 2008 - HC 698 10 11 see in particular @ paras10-12 in the Report (ibid ftn.19) above Professor Jeffrey Jowell QC and Professor Anthony Bradley P a g e | 12 52. Our predecessor Committee concluded in its Report on the Constitutional Role of the Attorney General that there should be power to give directions to end prosecutions in the national interest; there is a clear case for such a power, whether it is exercised by the Directors or by the Attorney General. However, the provisions relating to giving directions to halt proceedings or investigations by the SFO give rise to particular concerns: • The scope of the powers is too broad, since they are based on the Attorney General being "satisfied" which, in conjunction with the power to issue a certificate which is conclusive evidence of the need to make the direction, allows the Attorney General (and the Government on whose behalf the Attorney General acts) to take action in a controversial area without accountability in the courts. • The accountability to Parliament cannot be a sufficient safeguard since the Reports to Parliament are unlikely to contain all the information relating to making the decision to halt proceedings or an investigation.” As I trust, for reasons that the reader will now appreciate, the most concerning aspect of this part of the Report for me, is the apparent complete misapprehension under which this allimportant Parliamentary Committee was labouring when it thought that, an effect of a specific proposed statutory language, then in the Draft Bill, would be to effectively ‘oust’ the judicial review jurisdiction of the Courts ! It simply appeared to be unaware that, in relation to judicial review of the prosecutorial procedural powers of the Attorney-General, the Courts have already ‘banned themselves’, as it were, from the exercise of any such jurisdiction a long time since. Something which, with the benefit of such expert advice and testimony, one should surely be forgiven for hoping this Committee would have been well aware? Having thus set out its stall, the Committee’s conclusions as to the overall effectiveness of the Draft Bill, in achieving the stated objectives, were then as equally predictably forthright and uncompromising, as had been the case with the previous Constitutional Affairs Committee Report, as follows: “ 92. The functions of the Attorney General in relation to safeguarding the public interest in individual cases, e.g. the power to bring proceedings for contempt of court, power to bring proceedings to restrain vexatious litigants, power to bring or intervene in certain family law and charity proceedings and, most importantly, the power to bring or intervene in other legal proceedings in the public interest functions could be better performed by a non-political office holder. …. 105. The Prime Minister’s stated aims in respect of his constitutional reforms (as noted above in paragraph 4) are ambitious. His intention to forge a new relationship between Government and the citizen and to start a journey towards a new constitutional settlement which entrusts Parliament and people with more power is not likely to be assisted by the provisions in the Draft Bill relating to the Attorney General. 106. The Draft Bill fails to achieve the purpose given to constitutional reform by the Prime Minister: it gives greater power to the Executive and it does not sufficiently increase transparency.” P a g e | 13 Round Six: The Government’s Response to the Committee’s Response. (2009) It took the Government more than a year (July 2009) to respond to the Justice Committee’s Report (as above June 2008) by which time, of course, the Joint Committee on the Draft Bill had itself naturally completed its enquiries and reported (end of July 2008). However, in the interests of keeping the Reader’s focus, it seems appropriate to set out – at least in brief – the salient points of that Response, next in order. The formal Response12 begins with effusive thanks to the Justice Committee for its “commitment and contribution” to the debate, followed by profuse apologies for the Government’s delayed response – in short, the worst possible beginning ! The document then formally summarises the Government’s Response, as follows: “Summary The Government’s settled view is that the Attorney General should remain the Government’s chief legal adviser, a Minister and member of one of the Houses of Parliament, and that the Attorney General should continue as the Minister responsible for superintending the prosecuting authorities. That is not to say that important changes are not needed; the Government is clear that reform is required to clarify the Attorney General’s role and make it more transparent, with the result that public confidence in the role will be enhanced. To that end certain changes have been, or will be, made principally in relation to the Attorney General’s role as superintending Minister of the prosecution authorities As no change in the law is required to bring about these significant reforms the Government has decided not to bring forward any legislation relating to the Attorney General.” (emphasis by way of underlining added) So there we have it – after not just months but years of detailed analysis and deliberation, Government papers both Green and White, consultations and formal evidence sessions, etc., etc. all costing frankly millions – the end legislative product as a result … precisely nothing ! So far as concerned meaningful and permanent legislative reform of the role of the Office of the Attorney-General - forget it. With respect to the specific Justice Committee’s recommendations for legislative change the following extracts give a fair sample of the Government’s Response both to the detail, and indeed the overall critical analysis, which the Committee’s Report, had offered, as follows: “Recommendation 5 There has been doubt as to the meaning and extent of the power of superintendence in relation to individual prosecutions and the Government acknowledges that there needs to be particular clarity about the Attorney’s role in individual prosecutions. The Attorney General announced in 2007 that while the Government consulted on reform of the role she would not make key prosecution decisions in individual criminal cases except if the law or national security requires it. The Attorney General intends to continue with this practice. 12 The Government’s Response to the Justice Committee Report on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill (provisions relating to the Attorney General) Presented to Parliament by the Attorney General - July 2009 - Cm 7689 P a g e | 14 The Government does not believe that it will be necessary to make any legislative changes in this area. The Government believes that, through the protocol between the Attorney General and the directors of the prosecution authorities, the meaning of superintendence will be better understood. This will also bring greater clarity between oversight of the system and decisions in individual prosecutions. …. Recommendation 12 We are uncertain of the utility of the proposed abolition of the nolle prosequi, given that it is not clear by what it will be replaced. This reform is of little practical importance, given that it is so infrequently used, but it will in a small way remove some power over prosecutions from the Attorney General. (Paragraph 69) The Government has further considered the power to enter a nolle prosequi and come to the conclusion that it should be retained. The power is not used very often, indeed very sparingly, and usually only in a case where a defendant is ill and there is no other way of bringing the proceedings to an end. The Government has decided that the power serves a useful purpose and so does not intend to abolish it. …. Recommendation 18 The functions of the Attorney General in relation to safeguarding the public interest in individual cases, e.g. the power to bring proceedings for contempt of court, power to bring proceedings to restrain vexatious litigants, power to bring or intervene in certain family law and charity proceedings and, most importantly, the power to bring or intervene in other legal proceedings in the public interest functions could be better performed by a non-political office holder. (Paragraph 92) The Government considers that through combining the roles of the Attorney General, legal adviser, Minister, guardian of the public interest, each is strengthened. To move the public interest functions to a non-political office holder could diminish the importance of those functions, and remove accountability. …. Recommendation 21 The Draft Bill fails to achieve the purpose given to constitutional reform by the Prime Minister: it gives greater power to the Executive and it does not sufficiently increase transparency. (Paragraph 106) The changes to the role of the Attorney General that the Government proposes do not give greater power to the executive, but greatly enhance transparency and accountability. The Government’s intention in looking at the role of the Attorney General was to address those areas where there was potential for conflict while enhancing the administration of justice, the maintenance of the rule of law and the protection of the public interest.” Overall, the Government repeatedly falls back on the reference to the fact that, now it has been “determined” unnecessary to enact specific legislation, in order to achieve the requisite ‘desired reform’, the further improvements to accountability, clarity and public confidence can all be satisfactorily achieved as necessary piecemeal by various sub-legislative methods instead. P a g e | 15 Round Seven: The ‘Joint Committee’ & the Government’s Content Response (2008-9) Whilst, we have now just seen that the ultimate denouement for this Parliamentary versus Government game of constitutional amendment ping-pong, was the Government’s effective renunciation of legislative reform in its entirety, squishing its own ball, in a fit of constitutional pique - it is nonetheless, I believe, most instructive to examine the principal conclusions and recommendations of the parallel “Joint Committee on the Draft Bill”, and the all too predictable Government Responses thereto, if only so as to examine in a practical comparative acid test, what Sir Humphrey Appleby might doubtless have referred to as the administrative imperative of appointing the “right” people to a Committee ! I do not say for a moment that this Committee was simply an abundance of “place men” from top to bottom – take for instance the mixed qualifications of the Committee Chairman himself, the short lived Michael Foster MP (Hastings and Rye)13. On the one hand a holder of the ‘badge of maverick honour’, in that in 2003 he resigned from Government Office over his view that the Iraq invasion was illegal, without benefit of a second UN Security Council Resolution. Although, on the other hand, the Office from which he resigned was that of Parliamentary Private Secretary to the very Attorney-General who gave the legal ‘green-light’ to that international war crime, and that was an office to which, in short order, he found he was duly able to return after but a short interlude in a ‘moral martyr’s purdah’ !! However, when one also considers that the ‘leading lights’ in their ranks, on their Lordship’s side, included the likes of Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, a former Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Home Civil Service; and on the Commons side, Sir George Young (baronet) MP, later a Tory Government Chief Whip and Lord Privy Seal – the fact that their Report14 would be highly distinguishable from that of the House of Commons Justice Committee (and that of its predecessor the Constitutional Affairs Select Committee) was perhaps not merely predictable but frankly inevitable. Once again, analysis of both the “learned” evidence received from expert witnesses15, and the Committee Members own debate on the same, reveals that, as with the Justice Committee before it, this Committee also laboured under the apparent misapprehension that the relevant provisions in the Draft Bill dealing with the proposed powers of the AttorneyGeneral to close down individual criminal prosecutions on grounds of national security 16, would have the effect of an ‘ouster’ of the judicial review power of the Courts, without their apparently appreciating that the Courts themselves had long since declared they had no such power. As to the Joint Committee’s principal conclusions and recommendations, here are the selected highlights, most relevant to the topics presently under consideration: 13 14 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Jabez_Foster Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill : Session 2007–08 Volume I: Report printed 22 July 2008 and published 31 July 2008 HL Paper 166-I HC Paper 551-I 15 16 see in particular paragraph 112 of the Report. see in particular the then Clause 13 (5) of the Draft Bill. March 2008 - Cm 7342-II P a g e | 16 “ 84. We have carefully considered the evidence we have received and the recommendation of the House of Commons Justice Committee. We recognise that there are different and strongly held views on this issue. On balance, however, we are not persuaded of the case for separating the Attorney General’s legal and political functions. We therefore support the current arrangement which combines these functions, and support the retention of the Attorney’s present status as a Government Minister. …. 114. We sympathise with the Government’s concern to ensure operational independence for the prosecutorial authorities, but we are not convinced that removing the Attorney General’s power to give a prosecution direction is an appropriate route for achieving this. We were impressed by the strength of the evidence we received that the “nuclear option” of being able to stop a prosecution must be retained, and that the most appropriate person to exercise it is the Attorney General, as she is directly accountable for its exercise to Parliament. Removing this power would mean that the Attorney would have responsibility without power. We recommend that the Attorney General should retain the power to give a direction in relation to any individual case, including cases relating to national security. This should continue to be on a non-statutory basis. We see merit in the Attorney General reporting to Parliament if she gives a direction in relation to an individual case and we recommend that the Government establishes a procedure for the Attorney to do so. If, however, the Government removes the Attorney’s power to give a direction in an individual case, we agree that the Attorney should retain the power to intervene for the purpose of safeguarding national security, subject to the requirement to report to Parliament. …. 120. …. In response to these comments, the Attorney General conceded that the proposal to abolish the nolle prosequi power risked creating a “gap” in which neither the prosecuting authority nor the Attorney would be able to stop a prosecution. “For this reason we are considering whether it is appropriate to modify the powers of the main prosecuting authorities to discontinue proceedings [but t]his in turn raises difficult issues.” (Ev76) 121. In line with our recommendation in paragraph 114 that the Attorney should retain a power to direct, we recommend that the power to halt a trial on indictment (nolle prosequi) should be retained. We invite the Government to investigate how greater Parliamentary accountability for its use might be provided.” The reader will hopefully now no longer be surprised to learn that predictably the tone of the Government’s Response to these Recommendations, was to receive them with a very great deal more warmth than in respect to the very contrary views, as previously expressed by the Justice Committee. The Government saw fit to effectively concur with and welcome each and every one of this Committee’s recommendations instead17 ! Even going so far as to suggest at one point that perhaps this Committee was being too permissive of the AttorneyGeneral’s powers, stipulating that the AG’s hitherto “self-imposed” injunction on not 17 Government Response to the Report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty the Queen - July 2009 - Cm 7690 P a g e | 17 interfering with individual criminal prosecutions, unless required to do so by “the law or where national security requires it” would be continued – being careful to conclude, however, by saying that “the Government does not believe that it will be necessary to make legislative changes in this area.” 18 That, of course, remained the common theme, whereby the two paragraphs as quoted above, in the Summary of the Government’s Response to the Justice Committee’s Report, setting out its belief that the triplicate departmental political, government legal advisory and quasi-judicial prosecutorial superintendence functions, position and role of the Office of the Attorney-General, as it had been exercised to-date should continue, as before, unaffected, were repeated word for word19 ; inclusive of the devastatingly extraordinary conclusion that, in consequence thereof, the Government also now no longer saw the need for, and therefore did not now propose to make, any legislative reforms with regard to the same. The so-called “Protocol between the Attorney General and the Prosecuting Departments” (July 2009), with its explicit reference to the AG’s power to direct the DPP to not commence, or where already started discontinue or otherwise stop, a particular criminal prosecution wherever “ the Attorney General is satisfied that it is necessary to do so for the purpose of safeguarding national security”20 was published just a few days later. Finally, the Constitutional Reform & Governance Act, as it was ultimately styled, was passed and received the Royal assent on 8 April the following year – 2010 – just under one month before the General Election. It made provision in regards to management of the Civil Service, the ratification of international treaties, Parliamentary standards and the tax status of MPs and Lords, and minor amendments in relation to public records and freedom of information. The term “Attorney-General” does not appear in the Act from beginning to end and not a single word about any duty, function, role or power of the same occurs anywhere in it. Conclusions I said above in commencing Part II of this article that I was going to examine the performance of those whose duty it was to recommend necessary changes in the status quo, in the interests of ‘justice, the rule of law, motherhood and apple pie’ as our transatlantic cousins might say. Although, and openly facetious comment, I do believe it is apposite for the reader to here be reminded just how obviously and directly the issue of the reviewability of the Attorney-General’s powers is to the notion or principle of “government subject to the rule of law”. That general proposition was, of course, never so forcefully put as by Professor A.V. Dicey in his seminal work “Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution” (1885) wherein on the subject of “the Rule of Law” he holds : 18 see at paragraph 77 (P.17) of the Response. as to which see now paragraphs 17 and 18 in the Government's Response. 20 Per Ft.Nt. 5 above 19 P a g e | 18 “ It means in the first place, the absolute supremacy or predominance of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power, and excludes the existence of arbitrariness, of prerogative, or even of wide discretionary authority on the part of the government. Englishmen are ruled by law, and law alone; a man may with us be punished for a breach of the law, but he can be punished for nothing else. We mean in the second place, .... not only that with us no man is above the law, but (what is a different thing) that here every man, whatever his rank or condition, is subject to the ordinary law of the realm and amenable to the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals. ... With us every official, from the Prime Minister down to a constable or a collector of taxes, is under the same responsibility for every act done without legal justification as any other citizen. A Colonial Governor, a Secretary of State, a military officer, and all subordinates, though carrying out the commands of their official superiors, are as responsible for any act which the law does not authorise as is any private or unofficial person ... The ‘rule of law’, lastly, may be used as a formula for expressing the fact that with us the law of the constitution, the rules which in foreign countries naturally form part of a constitutional code, are not the source but the consequence of the rights of individuals, as defined and enforced by the courts ; that, in short, the principles of private law have with us been by the action of the courts and Parliament so extended as to determine the position of the Crown and of its servants; thus the constitution is the result of the ordinary law of the Land. “ Prof. AlbertVenn Dicey “Introduction to the Law of the Constitution” (1885) 10th. edn., London 1959, p.202-203 Perhaps in a more contemporary vein it would be equally valuable to compare this perspective with a modern day international declaration. Take for instance the following from the Secretary-General of the United Nations no less: “For the UN, the Secretary-General defines the rule of law as “a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal transparency." (Report of the Secretary-General: The rule of law and transitional justice in conflict and post-conflict societies” (2004)) It is not as if for instance, those engaged in our own system, at the practical end of prosecutorial discretion wielding, are unaware of the tremendous importance and significance of the power they wield with respect to the real world application of this principle in practice. See for instance, the following paragraph, again taken from the Attorney-General’s and Prosecutors Protocol (2009)21, as follows: 21 Ibid.Ft.nt.5 P a g e | 19 “4.1. The decision whether or not to prosecute, (or in the case of the SFO, to investigate and prosecute) and, if so, for what offence, or whether to use an out of court disposal, is a quasi-judicial function which requires the evaluation of the strength of the evidence and also a judgment about whether an investigation and/or prosecution is needed in the public interest. Prosecutors take such decisions in a fair and impartial way, acting at all times in accordance with the highest ethical standards and in the best interests of justice. In this way, prosecutors are central to the maintenance of a just, democratic and fair society based on a scrupulous adherence to the rule of law. “ And yet how are we, the mean and lowly subjects of the Crown, to be assured that this most worthy sounding appreciation, by our prosecutorial masters, of their pivotal role in the “maintenance of a just, democratic and fair society” is in practical reality “based on a scrupulous adherence to the rule of law”, and will be so scrupulously exercised on each and every occasion ? When, in practice, the most senior Officer of the Crown, who alone wields the greatest powers in this respect, is not only completely immune from examination by the courts for his or her decision-making, but moreover, is not even required to offer anyone any explanation or justification whatsoever for their prosecutorial decisions. Including, to be sure, so long as they continue to enjoy the confidence of their Cabinet colleagues – especially, of course the Prime Minister – in reality neither are they in truth answerable to Parliament, in any practical manner , and as respects any particular given decision instance. It is, of course, proudly asserted that, in the exercise of his or her enormous discretionary powers, the Attorney-General also acts in every way subject to the very same basic two-stage practical tests, as applies to all other Crown Prosecutors, as well22. Namely, as that is set out in the Code for Crown Prosecutors23 - with respect to (a) firstly the “Evidentiary sufficiency” test, followed then where necessary by (b) the “Public Interest” test. Yet, where it is their practice not to ever give grounds for their decisions, how are we expected to be so assured, that this practice has in each and every instance been so scrupulously followed? Is it simply that we are to take it always on trust? With respect, that is no way to run a private business, yet alone a constitutional monarchy. As a practical example, as to why only an idiot would take such matters on trust, take for instance this instructive exchange that occurred across the floor of the House of Commons in December 1999 – “ Nuclear Deterrence Policy HC Deb 13 December 1999 vol 341 cc39-40W 39W § Mr. Tony Benn To ask the Solicitor-General what advice he has sought on the legality of British nuclear deterrence policy. [102132] The Solicitor-General (Mr Ross Cranston). As a matter of convention (observed by successive Governments) neither the substance of the Law Officers' advice on a question, nor the fact that they have been 22 23 See esp. para 4(a)(2) of the Protocol (as above). as produced by the DPP pursuant to powers unders.10 of the PoA, 1985. P a g e | 20 consulted, is disclosed outside Government, other than in exceptional circumstances. I can however confirm that legal considerations are always taken fully into account in the formulation and application of defence policy. The Government are confident that Britain's nuclear policy and posture, as set out most recently in the Strategic Defence Review, are entirely compatible with our obligations under international law. § Mr. Tony Benn To ask the Solicitor-General what representations he has received about permission for a private prosecution of those responsible within [40W] Government for infringements of international humanitarian law based on the Government's nuclear deterrence policy. [102131] The Solicitor-General (Mr Ross Cranston). My office receives letters from the public from time to time on the Government's nuclear deterrence policy. A request for permission for a private prosecution under the Geneva Conventions Act 1957 was received last year. However, the Law Officers take the view that the application of the Government's nuclear deterrence policy does not involve an infringement of either domestic or international law, and accordingly permission was not given.” (emphasis by way of underlining added) “The law officers take the view that the application of the Government’s nuclear deterrence policy does not involve an infringement of either domestic or international law”!! Undeniably that at least has the merit of saving a very considerable sum in court costs ! But no pretense here then of this conclusion being a matter about which the Law Officers advice must remain confidential. No hint either that the “evidentiary sufficiency” test, nor even the “public interest” prosecutorial code tests, have been properly and scrupulously applied. Rather, a simple, bald and bare-faced statement that ‘we the Law Officers’ say that, in our considered view, the Government’s nuclear defence policy is ‘lawful, under both domestic and international law ‘– end of story. However, with the greatest respect, that is an example of Government will exercised by the law of force, and rests upon considerations particularly familiar to all manner of night-club bouncers up and down this land, and lies a million miles away from any notion of government subject to the rule, let alone force, of law instead. In light of these kinds of attitudes, I submit, it is no longer in the least surprising that the Appeals Committee of the House of Lords (as in Gouriet’s Case), in respect to the Attorney-General’s exorbitant discretion to control all access to the royal courts for the purpose of obtaining simple justice under public law - rejects even the limited notion of applying the principle of a jurisdiction for the judicial review of the excessive exercise of executive power, as an essential underpinning of the principle of government subject to the rule of law. Nor for that matter either, to observe an executive administration, in such an act of constitutional pique, as to revoke its own prior commitment to legislative reform, when faced with a commonsensical Commons Committee, committed to seeing genuine and meaningful political constitutional reform instead. P a g e | 21 So if then the Law Officers are to be held immune to judicial review, where then lies a practical solution to secure the ends for the rule of law ? “Mercifully our Constitution has, I believe, provided a remedy. It is what I have said already. If the Attorney-General refuses to give his consent to the enforcement of the criminal law, then any citizen in the land can come to the courts and ask that the law be enforced. This is an essential safeguard; for were it not so, the Attorney-General could, by his veto, saying ‘I do not consent’, make the criminal law of no effect. Confronted with a powerful subject whom he feared to offend, he could refuse consent time and time again. Then that subject could disregard the law with impunity. It would indeed be above the law. This cannot be permitted. To every subject in this land, no matter how powerful, I would use Thomas Fuller’s words over 300 years ago:’ Be you never so high, the law is above you’ 24 ‘tis a consummation devoutly to be wished. Robert L MANSON for and on the half of Institute for Law, Accountability and Peace. Fiat iustitia ruat cœlum 24 Denning MR in Gouriet’s Case (as above) in the Court of Appeal Gouriet v Union of Post Office Workers [1977] 1 AllER 696 (CA)