Too much trash and wasted time

advertisement

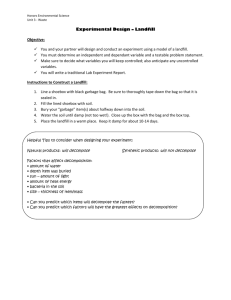

Chase Bennett May 3, 2013 Feature 2,091 words Too much trash and wasted time Sitting atop the highest geographical location in New Massive equipment runs over the trash a minimum of four times. Hanover County, Sam Hawes monitors the progress of the monstrous pieces of machinery. As he navigates the dust-covered pickup across the man-made plateau, the scent invades the trucks cabin; it smells like burnt popcorn and fresh asphalt. Several yards away the stench is similar to that of a chicken coop, and a little further from there the air is sickeningly sweet, like canned peaches A truck dumps its load… and becomes stuck. – rotting, canned peaches. “In another year or two, this cell will be complete.” Hawes, the NHC landfill manager, points to shallow basin at the foot of a steep grade. “We’ll start construction on that one soon so it will be ready in time.” Behind the truck, a bulldozer belts out a long note and an army of birds take off. “Seagull deterrent.” Landfill employees rotate the heavy equipment for cleaning every three days. There’s more to operating a landfill than meets the eye. Site workers must balance weather conditions, regulation and standard adherence, and customer service while performing a longestablished and repetitive routine. But despite all the hard work, the landfill is faced with a growing concern: how much longer will it last? In terms of solid waste management, NHC is years behind The idle WASTEC facility is set to be the drop-off point for hazardous house waste. much of the country, and cooperation from county officials and utilities is a rare event. The landfill, located right at the New Hanover-Pender County border, opened in 1981 amid speculation that New Hanover would condemn land in adjacent counties for the site. At that time, the Wilmington population, the largest contributor of solid waste, was around 44,000. By the time of the 2010 census the population had jumped to over 106,000. In 1984, WASTEC, the first waste-to-energy conversion facility in N.C., was built to offset 200 tons of solid waste per day from the landfill; in 1991 the facility was expanded to 500 tons. Unfortunately, as Wilmington expanded, funding for WASTEC upgrades and maintenance was reallocated for other uses. A combination of constant use, lack of funding for repairs, and contact with the salty air degraded the facility until it was no longer viable to maintain and was put off-line in April 2011. With WASTEC idle, the landfill experiences an average daily intake of 800 tons of solid waste. This influx has reduced the site’s life expectancy to 40-60 years. Such large amounts of waste comes with a multitude of problems, the most worrisome being environmental contamination. Construction and demolition waste is one of the most frequent, and bulkiest, types of waste encountered and poses a threat to the landfill machinery and lining. On average the site has 1,200 pounds of waste per cubic yard. But in 2009, Hawes and his employees were pressured to increase the weight to 1,800 pounds. This added weight and pressure increase the likelihood that construction was will penetrate the liner and allow pollutants to contaminate the ground water. Other dangers include potential fires deep in the landfill which can be caused by leaking chemicals and a number of other factors. These fires, which the NHC site experiences one to two times per year, can be difficult to deal with. The only effective method of extinguishing such fires is to dig up the affected area, one bulldozer shovel at a time, and manually snuff the flames. Of course, this results in lost productivity, money, and increased stress. Weather conditions can also decrease productivity. Any amount of rain forces the site operators to restrict civilian traffic to a small plot of land, but human errors and insufficient machinery can cause delays. A storm at the end of September 2010 brought 28 inches of rain; it took over two years for the site to fully recover. This time, a single night of rain has turned the main staging area into a soupy field. Hawes nods towards a truck dumping its contents into the diminished area. “See how the trash is compacted? He should be able to get out. If he’s stuck, that’s his fault – or the truck isn’t strong enough.” The wheels start spinning but there’s no forward movement. Sigh. “Now he’ll have to sign a waiver; they’ll chain him to a dozer and pull him out. It takes my guys away from their job and backs up the line.” As Hawes talks, two more trucks pull-up to unload. Three miles away, Joe Suleyman, the newly appointed director of the Department of Environmental Management, prepares for an upcoming meeting with the county commissioners. Since his arrival in June of 2012, Suleyman has been tasked with negotiating a contract that would revitalize WATEC. The main target has been Covanta, a New Jersey-based company that specializes in waste-to-energy technologies. Bringing WASTEC back online would be a major step-in dealing with NHC’s solid waste, and the Covanta contract was essential for this to occur. However, only one out of five county commissioners approved of the proposed deal in late 2012. All three of the newly elected commissioners actively campaigned against the revival of WASTEC and the contract was officially declined at the end of January. As of February, the facility was set to be partially deconstructed. The benefits of WASTEC would have been substantial. By converting 500 tons of the daily intake into energy via incineration, the landfills life expectancy would have increased anywhere from six to nearly a hundred years. The resulting ash could have been used as a substitute for the $200,000 of “clean dirt” the landfill uses annually for cover. Hawes believes that private enterprises may have greatly influenced the commissioners’ decisions since the original referendum to build the facility was approved by citizens on a 13:1 ratio. The loss of the Covanta contract sets the Dept. of Environmental Management back, but there are still options available. Suleyman will present various policy options to the commissioners, some of which are already underway and others that will be only marginally effective. One such option is the hazardous house waste drop-off site that will open May 15 in the WASTEC facility; this program will prevent dangerous chemicals from entering the landfill and ensure the recycling of reusable items. Another promising option is a proposed curbside yard waste collection service. It is estimated that 8.3% of the daily intake is vegetative debris — items that should not be headed to the landfill. The debris collected can be put to use as mulch, boiler fuel, and daily cover in place of dirt. Also, given the amount and type of debris received, this service has the potential to expand to collect food waste which could be used to start a composting service, the product of which being sold for profit or used in county landscaping. However, this is not to say that Wilmington residents haven’t been trying. Stan Harts, director of Environmental Safety and co-chair of the UNC Wilmington Sustainability Committee, had put in a bid to test ORCA food digesters at campus dining locations. Unfortunately, Cape Fear Public Utilities refused to issue the permit based on potential fats and biological oxygen demand. According to Harts, “We were willing to prove that they were below acceptable levels.” Although their analytical data proved that neither fats nor BOD would be an issue, CFPU still refused. “It could have been overturned but would have cost a significant amount is design and analytical fees. “ A third highly possible and effective option is a construction and demolition recycling facility. This debris is already separated at the landfill, but only by one employee and only if it has been properly disposed of. Construction debris improperly discarded is compacted with the rest of the incoming trash. This poses a threat to the landfill lining and the machinery, which is very expensive and vital to the day-to-day operations of the site. Suleyman has one “last resort” option thrown into the mix: a transfer station. In the event that more effective projects are not approved, this station would become the default option and would open the door to the end-all scenario. It is unlikely that an additional landfill could be established given the current regulations and zoning restrictions. Once the landfill reaches capacity trash must be shipped to waste disposal facilities in other counties if alternate options haven’t been adopted, an idea that Suleyman dislikes. “It’s a mentality of ‘ship it off, not my problem anymore.’ And I don’t believe in that.” Not only is the process of shipping waste to other counties a sign of noncooperation, it’s also a costly. The price per ton to ship solid waste out-of-county is determined by a transfer station fee, a hauling charge, and a transportation fuel surcharge. At current conditions this price is expected to be $14-16 per ton; this may not seem like much but given that NHC creates 800 tons of waste per day the annual transportation costs could easily exceed $3 million; this is assuming that the final destination is within 100 miles of the county. Although labor costs are included in the hauling charge, the increase in labor needed would likely be too much for the current budget to handle; the landfill has experienced a 50% staff-cut in the past 6 years. Alternative solutions are also on the horizon but are still just out of reach, such as “waste plasma arch gasification;” as much fun to say as it is difficult to comprehend. Essentially, garbage is pressurized and heated to temperatures high enough to liquefy it. This resulting liquid can then be used as fuel. However, the energy demands of this process are very high and current technology limits it to 300 tons per day. Foreign technologies are still being evaluated but may one day find a place in the U.S. For all the difficulties faced, the employees of the Dept. of Environmental Management have a lot to be proud of. New Hanover County saw the first waste-to-energy conversion in the state, however brief a time, as well as the first lined landfill – several years before policy was adopted to require it. The site is also a drop-off location for oyster shells, which are collected by the Division of Marine Fisheries and used to rebuild reefs and create suitable locations for oyster stocks. The pinnacle of the department’s success is seen in the creation of an artificial wetland. Wetlands are vital to the local geography as they provide water filtering services and act as a buffer for run-off and flooding. At the landfill, the wetlands take on the additional duty of filtering the leachate, any number of dissolved solids and fluids that act as pollutants, secreted by the capped and still-filling cells. The wetland is of simple design; two rows are filled with alternating bands of swamp grasses and pools. Pipes carry the leachate from the collection site beneath the cells to the pools between the grasses. The site has been quite a success, with filtered leachate being used a fertilizer for closed cells and the wetland now in its tenth year; typically, man-made wetlands fail within three to five years of creation. This site has also become popular with local wildlife. As the truck rounded a curve, multiple species of birds erupted from the grasses. Dozens of turtles can be seen sticking their heads out of the murky waters. Hawes states that there have even been claims of a visiting alligator and proof of a nesting bald eagle. Surprisingly, no one has come forward to The man made wetlands filter leachate and provide habitat for small wildlife species. take stock of the wildlife. “We’d love to have someone come out and do a species index. We’ve opened it up to the UNCW Biology Dept. but no one has shown interest.” Strangely, one row of the wetland has shown a considerable decline in productivity; many of the grasses are dead. Hawes has several theories as to what is happening. One possibility is that the row received an overload of leachate and is currently shocked. Another possibility is the unusually wet conditions seen at the landfill over the past several months; the rows location may be inhibiting the drainage of excess water and the plants have just drowned. More plants can be added to correct the balance but Hawes believes he’s seeing some improvement. “It may just take a little time to correct itself.” In general, NHC, and the U.S. in general is behind many other countries in terms of waste disposal and management. Part of this is due to different circumstances; the U.S. is not as stressed for space. However, NHC could benefit from the technologies of smaller, crowded countries such as France and the U.K. Although, the key to fixing the current situations is more cooperation from county entities and program involvement on the behalf of residents. Source List Beth Dawson — No response (910) 798-7260 bdawson@nhcgov.com Joe Suleyman (910) 798-4403 jsuleyman@nhcgov.com Jonathan Barfield, Jr. – No response (910) 233-8780 jbarfield@nhcgov.com Sam Hawes (910) 798-4454 shawes@nhcgov.com Stan H. Harts (910) 962-3108 hartss@uncw.edu Ashley Withers. “County officials say Covanta contract officially off the table.” StarNews Online. January 30, 2013. Retrieved from http://watchdogs.blogs.starnewsonline.com/22521/countyofficials-say-covanta-contract-officially-off-the-table/?tc=ar Ashley Withers. “Former WASTEC facility soon to disappear from landscape.” StarNews Online. February 20, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.starnewsonline.com/article/20130220/ARTICLES/130229980?p=1&tc=pg&tc=ar Gareth McGrath. “Filtering landfill juice.” Wilmington Star News. June 10, 2003. Retrieved from http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1454&dat=20030610&id=kRhPAAAAIBAJ&sjid=pR8 EAAAAIBAJ&pg=3557,2242233 John Meyer. “Law paves way for landfill outside county.” Wilmington Morning Star. January 9, 1981. Retrieved from http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1454&dat=19810109&id=iMEsAAAAIBAJ&sjid=tSY EAAAAIBAJ&pg=6201,1975322 Jonathan Spiers. “Landfill decided, but trash debate remains.” Port City Daily. January 22, 2013. Retrieved from http://portcitydaily.com/2013/01/22/landfill-decided-but-trash-disposal-debateremains/ Matt Soberg. “NC municipality plans to refurbish idled WtE facility.” Biomass Magazine. September 20, 2011. Retrieved from http://biomassmagazine.com/articles/5821/nc-municipality-plans-torefurbish-idled-wte-facility