Dora Chi Xu, Class of 2015

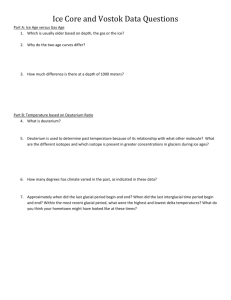

advertisement

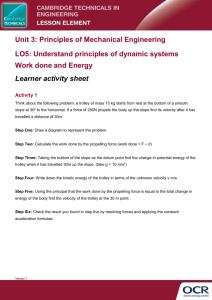

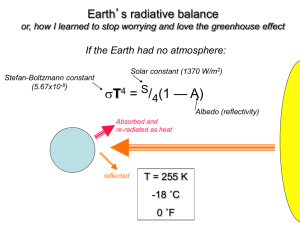

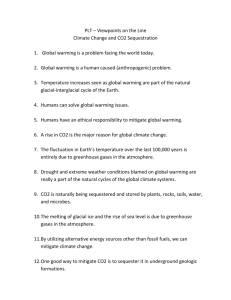

Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Dora Chi Xu, Class of 2015 New College House January 25, 2015 Dora Chi Xu, a geoscience major from China, will work as a post-baccalaureate research associate at the Earth and Environment Department in F&M, before pursuing an MD/PhD degree in geology/engineering. She is passionate about groundwater hydrogeology and hopes that she could eventually contribute to alleviating the global freshwater crisis. She is an explorer, tree-hugger, outdoor enthusiast, cook, painter, and is involved in African drumming and dancing, flamenco, and Bollywood dance. Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Many of you may have already heard about the famous trolley problem: Suppose there is a trolley that goes out of control and is about to kill 5 people tied to the railway ahead. You have the option to pull a lever that can direct the trolley to a sidetrack, where there is only one person. What would you do? Do nothing and let the trolley kill the five people? Or pull the lever to save them by sacrificing one? This moral paradox was first introduced by British philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967, and has been extensively analyzed by numerous psychologists, and neuroscientists (Thomson 1985). Yet, it raises a question that applies as much to human-earth interaction as to the traditional ethical, philosophical and psychological domains that focus on human-human interactions. Please keep the trolley problem in the back of your mind, as we will come back later to this discussion. As we reflect upon our position in human-earth relation, let’s first take a look at what the earth looked like at the beginning of human history. For the last 100,000 years, the temperature on earth has varied incredibly. The last 10 to 12 thousand years, however, have been remarkably stable in terms of temperature—This period is known as the Holocene era in geology. With the biogeochemical and atmospheric parameters fluctuating within a relatively narrow range, the Holocene has been an extraordinary benevolent time for humans, particularly when considered against the background of our planet’s tumultuous past (Dansgaard et al. 1993, Petit et al. 1999, Rioual et al. 2001). It is no coincidence that though human beings have been around for more than 90,000 years, not until Holocene era did we begin agriculture, and did humanity begin to flourish. Indeed, the end of the last ice age and the beginning of the warmer and more stable Holocene era has allowed humans to move freely, and achieve major shift in lifestyle and culture, such as transitioning from hunting and gathering to farming. The history of human civilization is a history of constant modification and manipulation of natural systems for the benefit of mankind. Geologists call this geoengineering. Agriculture, for example, the first and probably the most influential geoengineering, though unplanned in the first place, has been decisive in human evolution. Agriculture has laid the foundation for economically specialized societies, sedentary living, and hence permitting the accumulation of possessions, growing population, and further development of political systems, technology, etc. From an environmental perspective, geoengineering, such as agriculture, has had far-reaching influences on hydrology, vegetation cover, biodiversity, nitrogen cycles, and climate. Early human activities affected the functioning of the earth system. The imprints, however, were limited to local or regional scales (Steffen et al. 2007), because the earth has a capacity to restore equilibrium; nonetheless, that resilience is limited. Since the industrial revolution, humans have become the dominant driver of environmental changes and are now effectively pushing the planet outside the Holocene range of variability for many key earth system processes (Steffen et al. 2007). Indeed, the most essential activities of our society, such as energy and food production, transportation etc., have so thoroughly altered the world that a new geologic era Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma has been recognized and gaining wide acceptance: the Anthropocene, a new epoch of geological time characterized by dramatic planetary changes that are precisely linked to human activities (Crutzen, P. I. and Stoermer, E. F. 2000). Geologists are able to infer the traits of past epochs from the rocks that were deposited during those time intervals, and generally the progression from one epoch to another is marked by distinguishable, global stratigraphic events, such as bulk change in rock composition or mass extinction. Many scientific studies inferred that our activities have created a biological, geochemical or sediment signal that will be sufficiently different from that of the Holocene epoch, and will be preserved as a rock record for millions of years (Syvitski, 2012). In order to keep earth as a habitable planet, there are non-negotiable lines that we must not cross. Ample scientific studies enabled 9 planetary boundaries to be identified, delineating safe operating space for humanity. Transgression of the thresholds may trigger catastrophic, irreversible consequences within the continental to planetary scale system. These boundaries involve climate change, ocean acidification, stratospheric ozone, the nitrogen and phosphorus cycle, global freshwater use, biodiversity loss, chemical pollution and atmospheric aerosol loading (Rockström et al. 2009). These processes are deeply interconnected, and thus violating one boundary may dramatically affect the position of another. So, where are we at today? The first estimate on a global scale shows that for at least three of them, we have already broken through the environmental ceiling: 1) Too much green house gas has been released into the atmosphere, which indicates that we are on the verge of triggering catastrophic climate change. 2) We have created three times more reactive nitrogen than the planet can sustain. The disturbance of natural nitrogen cycle has a series of cascading effects from acid rain to soil, stream and groundwater contamination, costal eutrophication, and decreasing biodiversity. 3) Biodiversity is plummeting rapidly due to habitat loss, climate change, invasive species, overexploitation, and pollution, which would affect our food and energy security, and increase our vulnerability to natural disasters (Rockström et al. 2009). Undoubtedly, such proposed boundaries are preliminary estimates, whose accuracies are limited by uncertainties and knowledge gaps. However, our actions and choices will to a large degree determine how close we are to the critical thresholds, or whether we have crossed them. Instead of offering a roadmap, delineating planetary boundaries merely represents the first step to identify the directions to which we have the flexibility to choose a myriad of pathways to respond. If we can keep humanity pressure on the planet within these limits, then we may avoid pushing ourselves over the edge. Let’s take a look at climate change as an example. Methane (CH4) and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) are the major culprits of global warming; in fact, CH4 is 20 times more potent a greenhouse gas than CO2. The earth has a built in system, called orbital oscillation, which helps to control the rhythm of periodic variations of CH4 level in the atmosphere. According to the studies on ice cores in Greenland and Antarctica, 16 CH4 cycles recorded are in close correlation with orbital variations for the past 350,000 years (Rhodes et al. 2013). However, the last 8000 years show a widening divergence of CH4 from orbital oscillation, with insolation (i.e. solar radiation) going down and CH4 going up. Moreover, pollen and lake sediment functions as another independent proxy for climate. For instance, if the climate became colder, more water would be locked in the polar ice, and less would be evaporated from the ocean and transported to the land. Thus, the aridity would cause the forests to die off and give way to dry grassland. The seeds preserved in the sediment thus enabled scientists to reconstruct the paleoclimate. The overall drying of mid-latitude climate shown by pollen and Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma lake data indicates that CH4 should be lower, which means decreased global temperature (Marcia et al. 2003). That is to say, if the climate followed its regular path, we should have been in the ice age right now. So what happened to the 17th cycle? The answer is agriculture. The deviation of CH4 concentration from the projected pattern roughly corresponds to the first cultivation of rice and other grains (Crutzen, P. I. and Stoermer, E. F.: 2000). Surprisingly, inefficient early farming practices created a larger carbon footprint than we do today. CO2 also shows a similar divergence from natural patterns around 8000 years BP, which matches the anomaly of CH4. Early Anthropogenic hypothesis proposed that preindustrial forest clearance, farming and irrigation in Eurasia are more responsible for current global warming, since they emitted approximately 300 Giga Tons of Carbon (GTC), two times more than the commonly cited industrial emissions (Crutzen, P. I. and Stoermer, E. F.: 2000). Thus the question becomes: why did the atmospheric CO2 concentration stay at a relatively stable level during pre-industrial time and did not show significant increase until recently? The main reason lies in the long-term buffering effect of the ocean, which had absorbed most of the pre-industrial CO2 until the ocean reaches its capacity (Ruddiman,2003). If this hypothesis is true, the advent of agriculture by ancient people may be the true cause of anthropogenic climate change. Since there is a lag time between carbon emission and global warming, the bitter fruit that we are chewing today was actually planted 8000 years ago, by our ancestors. Does this news give you a chill creeping down the back? The CO2 that we pumped into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels has not really shown its power yet, but the storm is coming soon, and this time the ocean can no longer act as our protecting umbrella. Bombarded by the terrible things humans have done that may ultimately poison us into extinction, I’m sure that many of you, like myself, have been tired of hearing how severe the problem is, and are eager to learn about solutions to fix it. Let’s revisit the trolley problem. So the trolley is barreling down the rail, threatening to kill the five people. The first thing to ask is, how on earth were these five people on the tracks in the first place? There are plenty of safe places out there to walk and play. In the case of climate change, we tied ourselves to the deadly track, but it is not fair to simply put the blame on our ancestors. At the time when there were bountiful resources and a limited population, a slash-and-burn farmer could easily cut down the forests next door whenever his own field lost fertility. It seems difficult for them to have come across the idea of conservation, or contemplated what consequences their actions would have thousands of years later, when the world’s resources be depleted by a gigantic population. The most effective way, obviously, is to stop the trolley, but is it stoppable? Maybe not. With the exploding population and the economic growth of developing countries, our emissions are increasing exponentially. The projection of the CO2 emission has been heavily debated, and skeptics argued that environmentalists overestimated the emission just to make it look as bad as possible. However, emission levels of CO2 are now growing even faster than what we thought was the worst scenario just a few years ago. In fact, we have already crossed the CO2 concentration of 350 ppm, deemed one of the threshold, which has triggered a series of irreversible reactions in other systems (Rockström et al. 2009). For example, the warming climate has given rise to the melting of permafrost on the Tibetan plateau and high latitude areas such as the Arctic. This releases large quantities of CH4 that was frozen in the soil, which feeds the cycle of more warming and more melting. Similarly, the glacier retreat also exhibits such positive feedback: the melting of glaciers exposes more dark bare rock, which absorbs more solar radiation than the reflective ice does, and thus leads to more melting. In this regard, the trolley is ever accelerating. Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma What fuels the engine of the trolley? We have a global economy and civilization that is built on fossil fuels, and until we shift to a healthy mix of energy resources with the corresponding infrastructure, the world still runs on oil and gas. The struggle for petroleum has shaken the world economy, dictated the outcome of wars, and profoundly shaped the way we lead our daily lives. For example, at current technology level, we cannot find a substitute for airplane diesel fuel, because no other resources have the equivalent energy density. As the easy oil comes to an end, people are digging deeper and harder in the realm of unconventional petroleum. The heatedly debated Keystone XL pipeline and the explosion of shale gas drilling in Pennsylvania are two examples. Advocates claim that the unconventional petroleum is a “game changer”, since it contains 200 times the reserves than conventional oil and gas (Mackenzie, 2012), and the breakthrough in technology has transformed the U.S. from an energy-importer to an exporter. Besides achieving energy independence, the boom in unconventional petroleum industry is a strong economic stimulus and creates massive employment (Sander, Katie, 2014). However, the benefits that the unconventional petroleum brings cannot outweigh the trouble that it causes. First, the recovery of shale gas requires a technology called hydraulic fracturing. It demands energy to pump a large amount of water, mixed with toxic chemicals, to crack the shale open, artificially enlarging the permeability so that gas can flow out. It has raised serious environmental problems, such as water usage, pollution, public health issues, and human-induced earthquakes, to name a few. TransCanada spokesman claimed that the construction of Keystone XL pipeline will create 42,000 jobs, directed or undirected. However, such effect is only temporary. After the 2-year construction, the pipeline would employ about 50 people, primarily for maintenance (Sander, Katie, 2014). Furthermore, the same fossil fuel interests pushing the pipeline have been cutting, not creating jobs: the top 5 oil companies have reduced their U.S workforce by 11,200 employees between 2005 and 2010, in spite of earning $546 billion profit. Do those who survived the laid-off and working for the industry get paid higher wages? It turns out that 40% of the U.S. oil industry jobs consist of minimum wage work at gas stations. Another claimed benefit is to lower local natural gas price, but low domestic price means better markets elsewhere. Most of the pipelines in Pennsylvania converge at the port cities in Delaware or Maryland, which allows for easy export of the natural gas for fast-growing countries like China and India, and even post-Fukushima Japan. Above all, the most fundamental problem is that unconventional petroleum is not necessarily an energy resource, because its payback ratio is close to one. In other words, to get the energy out, we need to drill the well, pump the water and chemicals in, blow open the tight shale, extract the oil or gas out, refine it into usable form, and distribute it to where the demands are high…all of which requires energy from the almost depleted easy oil. Then how does the petroleum industry make profit? They can make money out of an energy sink thanks to the heavy subsidy from the government. Why are the renewable energy solutions less economical compared to petroleum? The renewables will be much more competitive if the petroleum was not as heavily funded; they will be more popular if they receive more subsidies and favorable policies. Unfortunately, the tangled relationship between the U.S. government and the petroleum industry is complicated and involves multiple layers of bureaucratic and legal ambiguity, making commitment to transforming current energy structure potentially difficult. The dominance of money in modern U.S. politics has now led to what termed as “quarterly democracy”, where officeholders running for reelection are required to publicly report their fundraising every three months. Even though we have the Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma capacity for long-term planning, such constant systematic stress has forced elected officials to focus intently on short-term horizons. This is especially precarious during a period of rapid change. Not all changes happen in gradual, linear fashion; sometimes the potential pressure can build up without visibly manifested until the critical threshold is reached. It’s as if we are all passengers of an airplane, whose pilot is steering without a reliable navigational instruments, and is instead pushing random buttons, hoping that we can somehow miraculously wind up landing in New York City. To quote Al Gore, the author of An Inconvenient Truth: “By tolerating the routine use of wealth to distort, degrade, and corrupt the process of democracy, we are depriving ourselves of the opportunity to use the” last best hope” to find a sustainable path for humanity.” The world’s need for intelligent, clear, valuesbased leadership is greater now than ever before-and the absence of any suitable alternative is clearer now than ever before. Even as we work our way to build a low-carbon economy, petroleum yet plays an indispensible role. Take solar energy development in Arizona for example, with more than 300 days of sunshine each year, and sizable wide-open, flat landscape that is ideal to install large-scale solar panels, the potential of solar power harvesting is enormous. According to a report by National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Arizona has the capacity to produce as much electricity from Solar Energy as the state consumes each year. Nevertheless, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. First of all, such estimate does not take into account of input energy and associated environmental impacts. Panel manufacturing requires Rare Earth Element, most of which currently come from China, and has already caused ecological degradation problems associated with mining. It also demands energy to transport the necessary raw material, to melt the glass, and to make the panels, which has a finite life span. Another factor to consider is the energy loss on the current inefficient transmission gridlines. According to the 2005 data from the Energy Information Administration, the US lost $19.5 billion on energy distribution (EIA, 2005). Other concerns revolve around the disturbance (such as the shading effect) on local ecological systems, potential vandalism problems, etc. Therefore, when taking a cradle to grave analysis, for every single form of renewable resources, we need to explore it, confirm it, recover it, convert it into usable form, distribute it, and dispose its waste after its lifetime, all of which requires energy that currently come from oil or gas. With the low-hanging fruit having already been picked, our energy future depends on how do we make the most out of the remaining fossil fuels. We can either invest them in transforming our energy structure to a self-sustaining one, or use them to tap into the unconventional petroleum, which is an energy black hole-- until the point that we do not have any energy to get more energy out. Are there other solutions to slow down the trolley or direct it into different directions? Some geo-engineering ideas have been proposed, many of which seemed crazy at first glance, but have recently attracted more attentions, as international efforts to limit carbon emissions have failed. I will briefly discuss two most popular ones. The first solution involves pumping seawater into the atmosphere to create clouds that reflect more sunlight. Stephen Salter from the University of Edinburgh and John Latham from the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado are the major promoters of this project. Their research shows that an increase in the albedo, that is, the reflectivity of the clouds by just 3% could offset previous human’s contributions to global warming (Salter, Sortino, and Latham 2008). According to Salter and Latham, the method will calls for a fleet of 1500 boats that spray 50 m3/s of seawater into the atmosphere. This might seem like a promising and simple method, but it begs the following questions: From where will the energy to run the ship and pump the water originate? How would the clouding effect influence the monsoon cycle, on which Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma millions of people rely for living? How about its impact on the aquatic system? Still, others argue that this is just a Band-Aid to the problem, since no one knows for sure how long the effects of the clouds would linger, and it does not lower the actual atmospheric CO2 levels at all. In fact, even if we stop pumping CO2 now, it will still take the earth about 200 years to absorb all the CO2 that is already out there. What about carbon capturing? Current carbon sequestering technology is very expensive, and involves injecting fluid CO2 into subterranean cavities, which have the risk of triggering earthquakes if the CO2 push open pre-existing faults. Yale scientists have presented another model showing that storage of CO2 in mafic rock- namely Magnesium (Mg) and Iron (Fe) rich rock-may be among the safest options (Viktoriya et al., 2013). Their theory is simple: weathering of mafic rock (e.g. basalt in Hawaii), the most ubiquitous on earth surface, consumes CO2. How do we know this will work? Earth’s history proved so. About 440 million years ago, the collision between offshore volcanic islands and the ancient North American continent, formed a series of mountain ranges, which constitute the current Appalachian Mountains. Such a mountainbuilding event, called the Taconic orogeny, plunged Earth into an ice age (Phil Berardelli, 2014). Why? Because the igneous rock created by the collision and volcanic activities, quickly reacted with CO2 in the atmosphere, which caused the earth to cool and the last ice age to begin. Can we mimic the result of the Taconic orogeny and fix the global warming problem? At the current rate, about 10 Giga tons (Gt) of carbon is produced annually, most of which come from burning fossil fuels and deforestation. Is it feasible to offset 10 Gt of Carbon per year by weathering mafic rock? Let’s do a mass and energy balance calculation: Natural weathering can remove about 0.1 Gt C/yr (Cotton et al., 2013). Although warmer temperature increases this rate, natural carbon sequestering is still vanishingly small. However, we can speed up the process by crushing mafic rocks and spreading them to expose to water and atmosphere. Theoretically, it will take 15 Gt of mafic silicate to remove 10 Gt of CO2 (IEA, 2009). What does this figure mean? Comparing to coal mining, which has an annual production of 8 Gt, it requires a mafic rock mining industry about 2 times the size of global coal mining industry. The required energy is about 4.7 to 9.4 Quadrillion Btu per year, about 0.8% of the world total primary energy consumption, at a cost of 0.01% of GDP. If we take the energy input and emission generated from mining, crushing, and transportation into consideration, and subtract that from the CO2 sequestered, we can calculate the offset efficiency: 90%. So, should we do it? The efficiency is favorable, and the method is energetically possible. Is it economically viable? There is yet no profit in the silicate mining industry, unless we achieve an international treaty to make it a lucrative commodity. Who will pay for it? Are there any other environmental impacts? How do we anticipate and quantify them? To acquire mafic rock in such large quantities, we might need to grind up 1/3 of Australia (which has the world richest Fe-Mg rich minerals, the Australians wouldn’t be happy though). Even if we sacrifice 1/3 of Australia, would it be enough to reverse global warming? Since the world economy continues to grow, and the carbon emission is increasing exponentially, what if we eventually run out of mafic rock? “Well, don’t worry,” as my geology professor Tim Bechtel remarked sarcastically, “humans are good at finding engineering solutions, the moon is full of mafic basalt.” To fix a problem we came up with an engineering solution, which triggered unintended consequences; to fix the unintended consequences, we found a new engineering solutions to it, which, of course, can give birth to even more unintended consequences…Does our interaction with earth bear a striking resemblance with the old nursery song: There was an old lady who swallowed a fly, to catch the fly she swallowed a spider, to catch the spider she swallowed a bird, then a cat, a dog, a cow, and a horse…she’s dead in the end, of course! Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Nevertheless, it is important to think seriously about geo-engineering because we may need to use it as a fast and temporary risk control but not as a substitute for long-term action. This is due to the enormous amount of leverage that geo-engineering can bring, and there are times that we may want a fast solution to bring the fever down. Opponents argue that the knowledge that geo-engineering is possible makes climate change less fearsome, and therefore a weaker commitment to cutting emissions today (Bunzl, 2008). That is what David Keith, a Canadian environmental scientist, called a moral hazard, and that is one of the underlying reasons why it is so politically hard to talk about this. But you do not make better policies by hiding things in a drawer. Now we shall return to the trolley problem that I posed in the beginning of the paper. The trolley is unstoppable. Do we have a moral obligation to prevent a disaster from happening? No matter which way we choose, there are always trade-offs. Who should decide? Based on what criteria? Would the greater good always outweigh the minority? How do we know whether or not our good-intended actions could lead to even more disasters? There are always doubts in science, and the intrinsic uncertainty lies in how complex the system will behave, such as its feedback mechanisms and the interactions among variables. In other words, we may possess dots of knowledge, but we do not fully understand how the dots are connected and how exactly they interact with one another. One single action may trigger a chain of reaction, producing cascading, irreversible consequences. To phrase the question another way: How do we do what we do, without knowing that we don’t know? Should we wait? Can we afford to wait? These are complicated questions and have no clear-cut answers, but the science necessary to make consequential decisions, should come from our generation. From a socioeconomic perspective, it is hard to put a brake on this very high inertia fossilfuel based-economy, because simply finding out a better, more powerful way to do things does not necessarily guarantee readily acceptance. The problem could be absolutely soluble in terms of science and engineering, but it is politically hard because there are always winners and losers. We need a broader debate, a debate that involves industry leaders, scientists, engineers, politicians, economists, philosophers, writers, and general public. It is time that we think clearly about the obvious trend that are ever gaining momentum; it is time that we reason together and attend to the powerful changes that are now underway. Why should we care? German pastor Martin Niemöller has a famous poem:” First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionist, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.” The cowardice and lament for the 20th Century German Holocaust applies as much to today’s apathy toward global warming and other issues confronted by the entire human race. Is climate change merely a threat for lowlying countries like Bangladesh or the Maldives? Why do we need to care whether the Greenland’s ice melting would wipe out some of the largest cities from the world map? Should we always consider us in the position of pulling the lever? Or are we actually the one on the track? The following Native American proverb put it succinctly:” We do not inherit the land from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.” We are the children. Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Acknowledgement I’m grateful to professor Suzanna Richter, who introduced me to the Marcellus Shale controversy in first year seminar and opened my eyes to a whole range of environmental issues. I’m deeply indebted to professor Tim Bechtel, who taught me everything from introductory geology, unconventional petroleum, to geo-engineering and karst hydrogeology. Thanks also to my dear friends Cinthia Liu, Lydia Baird, Andy Foley, and Aaron Blair for proofreading my paper and offering their valuable insights. Bibliography Berardelli Phil,2009. “The mountains that froze the world”. Science AAAS Bunzl M. 2008. “An Ethical Assessment of Geo-engineering.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 64(2):18-18. Crutzen, P. I. and Stoermer, E. F., 2000. "The Anthropocene", 2000. IGBP’s Global Change magazine (Newsletter 41) Cotton, Jennifer M., M. Louise Jeffery, and Nathan D. Sheldon. 2013. “Climate Controls on Soil Respired CO2 in the United States: Implications for 21st Century Chemical Weathering Rates in Temperate and Arid Ecosystems.” Chemical Geology 358 (November): 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.08.048. Dansgaard, W., S. J. Johnsen, H. B. Clausen, D. Dahl-Jensen, N. S. Gundestrup, C. U. Hammer, C. S. Hvidberg, J. P. Steffensen, and A. E. Sveinbjörnsdottir. 1993. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record. Nature 364:218–220. Mackenzie et al., 2012. "access to gas-revisiting the LNG industry's big challenge". Edinburg and London, UK. Marcia. Phillips, Sarah M. Springman, and Lukas U. Arenson. 2003. International Conference on Permafrost, Permafrost: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Permafrost, 21-25 July 2003, Zurich, Switzerland. Rotterdam; London: A.A. Balkema ; Momenta. Petit, J. R., J. Jouzel, D. Raynaud, N. I. Barkov, J.-M. Barnola, I. Basile, M. Bender, J. Chappellaz, M. Davis, G. Delaygue, M. Delmotte, V. M. Kotlyakov, M. Legrand, V. Earth, Humans, and the Trolley Dilemma Y. Lipenkov, C. Lorius, L. Pépin, C. Ritz, E. Saltzman, and M. Stievenard. 1999. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420 000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antartica. Nature 399:429–436. Rioual, P., V. Andrieu-Ponel, M. Rietti-Shati, R. W. Battarbee, J. L. de Beaulieu, R. Cheddadi, M. Reille, H. Svobodova, and A. Shemesh. 2001. Rhodes, Rachael H., Xavier Faïn, Christopher Stowasser, Thomas Blunier, Jérôme Chappellaz, Joseph R. McConnell, Daniele Romanini, Logan E. Mitchell, and Edward J. Brook. 2013. “Continuous Methane Measurements from a Late Holocene Greenland Ice Core: Atmospheric and in-Situ Signals.” Earth and Planetary Science Letters 368 (April): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.02.034. Rockström, Johan, W. L. Steffen, Kevin Noone, \AAsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin III, Eric Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton, et al. 2009. “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/iss_pub/64/. Ruddiman, W. F. (2003), The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago, Clim. Change, 61, 261 – 293. Salter, Stephen, Graham Sortino, and John Latham. 2008. “Sea-Going Hardware for the Cloud Albedo Method of Reversing Global Warming.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 366 (1882): 3989–4006. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0136. Sander, Katie, 2014 " TransCanada CEO says 42,000 Keystone XL pipeline jobs are 'ongoing, enduring' New York Times Steffen, W., P. J. Crutzen, and J. R. McNeill. 2007. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of Nature? Ambio 36:614–621. Syvitski J P M and Kettner A J (2011). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 369: 957-975 Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1985. “The Trolley Problem.” The Yale Law Journal 94 (6): 1395. doi:10.2307/796133. Viktoriya M. Yarushina* and David Bercovici,2013. "Mineral carbon sequestration and induced seismicity". Geophysical Research Letters Volume 40, Issue 5, pages 814– 818, 16 March 2013