Session IV

UNPLUGGED: THE PHYSICS OF A ACOUSTIC GUITAR

James Reber

American University

4400 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, DC. 20016-8058, jr4063a@student.american.edu

Abstract — The acoustic guitar is one of the world’s most

easily recognized instruments. This paper discusses the

physics of the acoustic guitar with a focus on the

soundboard. The paper begins with a discussion of what

sound is and how it travels, focusing on the aspects

important to understanding how a guitar works. The paper

then discusses the most common bracing patterns for nylon

and steel string guitars, and how the final shaping of the

braces affects both the strength and the performance of the

instrument. For the shaping of the braces, this paper

discusses the physics behind the free plate tuning technique.

Furthermore, this paper looks at experimental bracing

techniques and the reasoning behind the different patterns.

Index Terms — Acoustic

soundboard, sound waves,

guitar,

bracing

patterns,

INTRODUCTION & GUITAR DESIGN

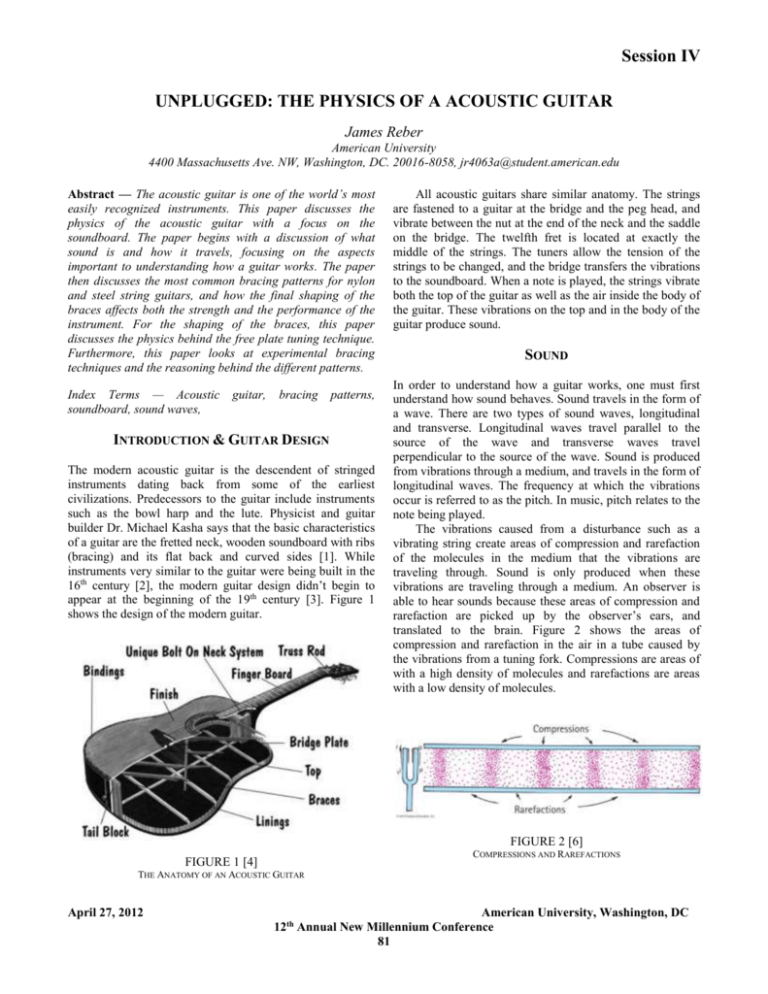

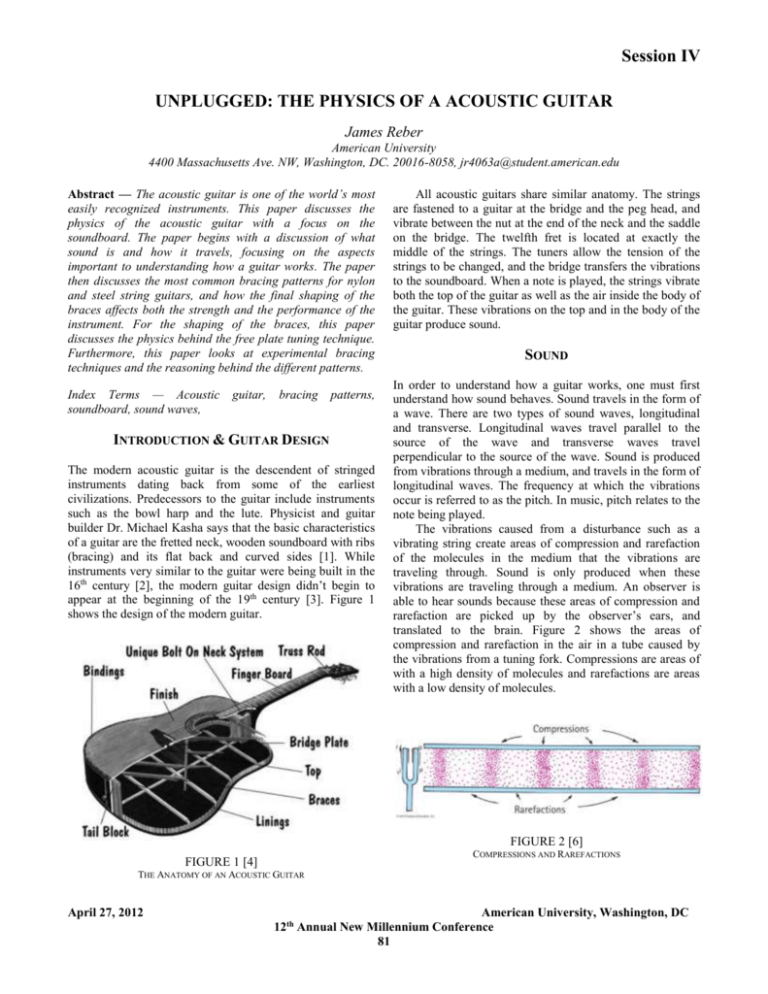

The modern acoustic guitar is the descendent of stringed

instruments dating back from some of the earliest

civilizations. Predecessors to the guitar include instruments

such as the bowl harp and the lute. Physicist and guitar

builder Dr. Michael Kasha says that the basic characteristics

of a guitar are the fretted neck, wooden soundboard with ribs

(bracing) and its flat back and curved sides [1]. While

instruments very similar to the guitar were being built in the

16th century [2], the modern guitar design didn’t begin to

appear at the beginning of the 19th century [3]. Figure 1

shows the design of the modern guitar.

All acoustic guitars share similar anatomy. The strings

are fastened to a guitar at the bridge and the peg head, and

vibrate between the nut at the end of the neck and the saddle

on the bridge. The twelfth fret is located at exactly the

middle of the strings. The tuners allow the tension of the

strings to be changed, and the bridge transfers the vibrations

to the soundboard. When a note is played, the strings vibrate

both the top of the guitar as well as the air inside the body of

the guitar. These vibrations on the top and in the body of the

guitar produce sound.

SOUND

In order to understand how a guitar works, one must first

understand how sound behaves. Sound travels in the form of

a wave. There are two types of sound waves, longitudinal

and transverse. Longitudinal waves travel parallel to the

source of the wave and transverse waves travel

perpendicular to the source of the wave. Sound is produced

from vibrations through a medium, and travels in the form of

longitudinal waves. The frequency at which the vibrations

occur is referred to as the pitch. In music, pitch relates to the

note being played.

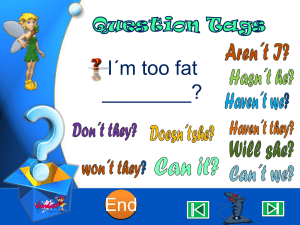

The vibrations caused from a disturbance such as a

vibrating string create areas of compression and rarefaction

of the molecules in the medium that the vibrations are

traveling through. Sound is only produced when these

vibrations are traveling through a medium. An observer is

able to hear sounds because these areas of compression and

rarefaction are picked up by the observer’s ears, and

translated to the brain. Figure 2 shows the areas of

compression and rarefaction in the air in a tube caused by

the vibrations from a tuning fork. Compressions are areas of

with a high density of molecules and rarefactions are areas

with a low density of molecules.

FIGURE 2 [6]

COMPRESSIONS AND RAREFACTIONS

FIGURE 1 [4]

THE ANATOMY OF AN ACOUSTIC GUITAR

April 27, 2012

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

81

Session IV

FORCED VIBRATIONS

(3)

The volume of a sound depends on the amount of air that is

moving due to the vibrations created from the sound source.

When an object that is vibrating is held against another

object, the second object will also vibrate. This is called

forced vibration. If the second object has a larger surface

area, the vibrations will move more air, making the volume

louder. One of the main physics principles that apply to an

acoustic guitar is forced vibrations. Forced vibrations occur

when a vibrating object forces another object to vibrate.

Hewitt uses the example of a tuning fork placed on a table.

The vibrating tuning fork forces the table to vibrate at the

same frequency. The vibrating table moves more air

molecules than the tuning fork alone, and therefore produces

a higher volume [7]. On a guitar, the vibration of the strings

is transferred to the soundboard through the bridge, forcing

the soundboard to vibrate at the same frequency as the

string, which produces sound.

HOW A GUITAR FUNCTIONS

There are two different kinds of guitars: classical and folk.

The main difference between a classical and a folk guitar is

the type of strings used. Classical guitars use nylon strings

and folk guitars use steel strings. Both types of guitars are

tuned to the same frequencies, but the nylon strings have a

much lower density than steel strings, and therefore the

tension on the soundboard of the guitar is much less for a

classical guitar than a folk guitar. The bracing for a steel

string guitar must be much stronger than the bracing of a

classical guitar in order to handle the increased force on the

soundboard due to the steel strings.

When a note is played on the guitar, the string vibrates

back and fourth producing a wave. The frequency of the note

is determined by the velocity of the wave on the string

divided by the wavelength, shown in (1).

(1)

A guitar has six strings, each one of a different thickness and

tuned to a different frequency. The strings must be different

thicknesses because the velocity of a wave on a string

depends on the tension, and the linear mass density of the

string, shown in (2), where is the velocity, is the tension

and is the linear mass density. The thicker strings have a

lower frequency, and the thinner strings have a higher

frequency. This is because thicker strings have a higher

linear mass density, which reduces the velocity of the wave

on the string for a given tension, and the result is a lower

frequency. Linear mass density is expressed in (3), where

is the mass of the string and is the length of the string.

April 27, 2012

Regardless of whether or not a guitar is strung with

nylon or steel strings, the frequency of the open strings, or

the frequency produced when a string is not fretted, is not

changed. Depending on the size of the instrument (and

therefore the wavelength of the string), the velocity will

change. For a given frequency, a long wavelength means a

lower velocity, and a short wavelength means a higher

velocity. The strings on all guitars in standard tuning are

tuned to the same frequencies, despite the length of the

strings. Small guitars are tuned to the same frequencies as

larger guitars. Table 1 shows the pitch as well as the

frequencies of a guitar in standard tuning. The number after

the letter name of the pitch refers to the octave at which the

pitch is heard [8].

TABLE 1

GUITAR STRING NOTES AND FREQUENCIES

String

1

2

3

4

5

6

Pitch

E2

A2

D3

G3

B3

E4

Frequency

82 Hz

110 Hz

147 Hz

196 Hz

243 Hz

330 Hz

The tension on the bridge of the guitar due to the strings

varies depending on the material of the strings due to the

change in the linear mass density. Table 2 compares the

tension of the most common gauge of nylon and steel

strings. The tensions shown in Table 2 are based on the most

common scale length of each style of guitar; 25.6 for nylon,

25.4 for steel.

TABLE 2 [9]

NYLON AND STEEL STRING TENSIONS

String

1st E

2nd A

3rd D

4th G

5th B

6th E

Total

Nylon (Normal Tension)

14 Lbs

15 Lbs

15.6 Lbs

12.1 Lbs

11.6 Lbs

15.3 Lbs

83.6 Lbs

Steel (Light Gauge)

25.1 Lbs

28.4 Lbs

29.5 Lbs

29.4 Lbs

23.3 Lbs

23.3 Lbs

159 Lbs

In order to change the note being played, the player

changes the wavelength of the string by shortening the

length of the string with their fingers. The velocity of the

wave on the string remains constant, and by shortening the

length of the string the frequency increases [10].

The wavelength for a string on a guitar depends on the

(2)

scale length of a guitar, or the distance from the nut near the

headstock of the guitar to the saddle on the bridge, with the

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

82

Session IV

twelfth fret being in the middle. The first harmonic, or the

fundamental, shown in Figure 3 shows the motion of a

plucked open string (vibrating between the nut and the

saddle), which is half the wavelength of the wave on the

string. This is known as the first harmonic. Harmonics are

whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency. The

second harmonic is formed on a guitar by creating a node at

the twelfth fret and is twice the frequency of the open string.

Creating a node at the fifth or seventeenth fret forms the

third harmonic and the frequency is three times higher than

the open string [11].

vibration of the air inside the body of the guitar as well as

the high frequencies projected from the vibration of the

soundboard gives the guitar its unique sound.

THE OVERTONE SERIES

Every instrument’s sound quality or timbre is different due

to the instrument’s unique overtone series. When a note is

played on a guitar, the pitch that is heard is the fundamental

frequency. There is also a combination of other frequencies,

known as partial tones or harmonics, which are emitted

along with the fundamental frequency. The volumes of these

partial tones affect the timbre or tone of the instrument. The

amount of partial tones and the volume of each partial tone

for a note make every instrument sound different. The

combination of these partial tones is known as the overtone

series [14]. Figure 4 shows an example of the amplitude of

the different frequencies produced from a single note played

on a guitar, with the first peak being the fundamental

frequency. The x-axis shows the frequency of each overtone

and the y-axis shows the intensity of each of those

frequencies.

FIGURE 3 [12]

WAVES ON A GUITAR STRING

There are two different phenomena that make the

conversion of the mechanical energy from the player

plucking a string to sound energy more efficient, and

therefore louder. Dr. Wolfe notes that a guitar does not

amplify the sound from the vibrations of the strings. First,

when the string vibrates above the sound hole of the guitar,

the vibrations of the strings create areas of compressions and

rarefaction in the air around the sound hole. These vibrations

compress the air inside the body of the guitar, which raises

the internal pressure. The air is then forced out due to the

high pressure. This is referred to as Helmholtz resonance.

The vibration of the air inside the body of a guitar mostly

affects the lower frequencies, so a guitar with a smaller body

would produce softer low frequencies. This becomes

apparent when looking at the violin family of instruments.

The lower pitched instruments such as the cello or bass have

larger bodies than the violin of viola.

The other way that a guitar converts the mechanical

energy to sound energy is through the vibration of the top of

the guitar. The top or soundboard is designed to vibrate, and

because of its large surface area, the vibrations move more

air than the string alone could. The vibrating soundboard is

an example of forced vibrations. The strings vibrate against

the bridge, which forces the soundboard to vibrate. The

soundboard projects the higher frequencies of a guitar into

the air around the guitar. The more surface area of the

soundboard, the louder the produced frequencies are [13].

The combination of the low frequencies projected from the

April 27, 2012

FIGURE 4 [15]

GUITAR OVERTONE SERIES

The overtone series is unique for not only every

instrument, but also every guitar. There are several

components that affect the overtone series of a guitar, from

the woods used for the instrument to how the strings are

plucked. Arguably the leading factor that affects the

overtone series of a guitar is the bracing on the underside of

the soundboard.

SOUNDBOARD BRACING

The purpose of the bracing of a guitar is to both provide

support against the soundboard warping due to the tension of

the strings as well as help transfer the vibrations of the

strings to the soundboard. Ideally, the bracing transfers the

vibration of the strings to the entire soundboard of the

instrument.

In about 1850 Antonio Torres of Spain introduced a

fanned bracing pattern on his nylon string guitars. His

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

83

Session IV

bracing pattern provided sufficient strength to the

soundboard of the guitar as well as enhanced the tone of the

instrument. This pattern has remained one of the most

common bracing techniques used for classical guitars to this

day [15]. Figure 5 shows the Torres bracing pattern.

FIGURE 5 [16]

TORRES BRACING PATTERN

Steel guitar strings began to become available by the

early 20th century and proved to provide louder volumes than

nylon strings. While Torres’ pattern was sufficient for nylon

strings, the increased tension of the steel strings was too high

and caused the soundboard to warp. To compensate for this,

guitar builders began using an X bracing pattern, which

provided more support for the soundboard. Christian Martin

who founded C.F. Martin guitars in the 1830’s was an

innovator of the X bracing pattern [17]. Figure 6 shows

Martin’s X bracing pattern.

soundboard with bracing because the soundboard would be

free to vibrate, but the tension of the strings would cause the

wood to warp, making the instrument unplayable. Guitar

builder Bert Eendebak explains that the structural

requirements of a guitar harm the musical quality of the

instrument [18].

The soundboard of a guitar oscillates in different

patterns depending on the frequency of the note being

played. One way to visualize these patterns is with Chladni

figures. Chladni figures provide a visual reference for where

the nodes are located. When the soundboard is vibrating at a

certain frequency, there are areas that on the soundboard that

do not vibrate due to standing waves, or stationary waves.

Standing waves occur when two opposing waves of the same

wavelength and amplitude meet and cancel. When a material

such as sand or some kind of power is placed on a plate (or

soundboard) that is vibrating at a certain frequency, it is

attracted to the areas that are not moving, or nodes [19].

Figure 7 shows and example of two nodes marked “N”.

FIGURE 7 [20]

NODES

The nodes are formed on a guitar soundboard when

waves encounter each other and cancel. Even if one note is

plucked on a guitar string, the interference of the vibrations

on the soundboard still form nodes. Figure 8 shows how the

interference between waves of the same wavelength forms

nodes. The green and blue lines represent two interfering

waves and the red line shows the amplitude of the resulting

waveform.

FIGURE 6 [18]

MARTIN X BRACING

Martin’s X bracing pattern has remained the standard

for steel string guitar bracing while Torres’ fan bracing

pattern has remained the standard for nylon string guitars.

VIBRATIONS ON THE SOUNDBOARD OF A GUITAR

The soundboard of a guitar is designed to oscillate due to the

vibrations of the strings. The more that the soundboard is

able to flex, the more volume the instrument produces

because of the higher amount of air being vibrated. A

soundboard with no bracing would be much louder than a

April 27, 2012

FIGURE 8 [21]

NODES FORMED BY WAVE INTERFERENCE

Figure 8 shows nodes created from waves traveling in one

dimension. Waves on the soundboard of a guitar travel in

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

84

Session IV

two dimensions. Figure 9 shows the pattern of the nodes

formed on a guitar soundboard at 77 Hz, 375 Hz and 511

Hz. These patterns are examples of Chladni patterns on the

soundboard of a guitar. The black lines show the areas of no

vibration or the nodes on the soundboard.

Once the frequency that forms the ring-and-a-half

pattern is found, the braces on the soundboard can be shaped

to improve the pattern. The goal is to have a perfect circle

below the sound hole where the bridge is attached as well as

a perfectly curved line above the sound hole [25]. By

changing the height and width of the braces, the resistance

against flexing is changed. A thinner brace will flex more

than a thick brace. Equation (4) shows the relationship of

how height and width of a brace affects the resistance

against bowing, where is the resistance,

is the width of

the brace and is the height of the brace [26].

(4)

FIGURE 9 [22]

NODES ON A GUITAR

Chladni figures can be helpful in guitar construction.

Guitar builders can use the patterns to determine how the

bracing on the soundboard needs to be altered. Altering the

bracing on the soundboard until a desired chladni pattern is

found is referred to as free plate tuning.

FREE PLATE TUNING

While the patterns formed on the soundboard depend on the

shape and material of the soundboard, the patterns can be

useful for the final shaping of the braces. While the main

purpose of the braces is to provide structural support for the

soundboard, they also help transmit the vibration of the

strings to the entire soundboard. The braces must be shaped

in such a way that the stiffness to mass ratio of the

soundboard is the same in all directions.

One method of ensuring that the stiffness to mass ratio

is consistent along the soundboard is by using the ring-anda-half method. In order to use this method, the soundboard is

vibrated at different frequencies until a Chladni figure forms

where the nodes form a ring below the sound hole, and half a

ring above the sound hole. The frequency at which this

pattern occurs varies depending on the soundboard being

tested [23]. Figure 10 shows a pattern very close to the ringand-a-half pattern.

When constructing the soundboard for a guitar, the

braces are shaved down, reducing the resistance against flex,

until the ring-and-a-half pattern is perfect. When the ringand-a-half pattern is perfect, the stiffness to mass ratio of the

soundboard is isotropic, or consistent across the entire

soundboard [27]. The thickness of the bracing also has effect

on the tone or timbre of a guitar. Guitars with heavy bracing

have better tone, but less volume. This is due to the fact that

the heavy bracing doesn’t allow the soundboard to vibrate as

well, therefore moving less air. Lighter bracing does not

transmit the vibration of the strings to the soundboard as

efficiently as thick bracing, but it allows the soundboard to

vibrate more because it is less stiff, producing more volume

[28].

EXPERIMENTAL BRACING PATTERNS

While the X bracing pattern for steel string guitars and the

fan-bracing pattern for nylon string guitars have been the

most commonly practiced bracing techniques, some guitar

builders have experimented with alternative bracing patterns.

One of these alternative patterns is the Kasha bracing pattern

for nylon string or classical guitars. In the 1960’s, Dr.

Michael Kasha created an asymmetrical bracing pattern that

he based on Chladni figures for circular plates. His goal was

to create a guitar that produced more volume and better tone

than classical guitars with the traditional fan bracing. Figure

11 shows Kasha’s bracing pattern.

FIGURE 11 [29]

FIGURE 10 [24]

THE KASHA SOUNDBOARD

RING-AND-A-HALF PATTERN

April 27, 2012

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

85

Session IV

Kasha’s design addressed the issue of heavy bracing

producing good tone but low volume and light bracing

producing high volume but poor tone. The lower notes on a

guitar have more amplitude due to their increased mass, and

therefore force the soundboard to vibrate more than the

higher notes make it vibrate. Kasha’s bracing pattern

simultaneously achieves the ideal conditions of heavy

bracing for low notes and light bracing for high notes [30].

SUMMARY

There are many elements that go into producing a quality

guitar. Both classical and folk guitar builders strive to

produce instruments with good tone as well as powerful

volume. While there is a lot to be said about the materials

used in constructing a guitar, one can argue that the bracing

is one of the most important aspects. Guitar builders, also

known as luthiers, are constantly making adjustments to the

standard X bracing and fan-bracing patterns in order to

create an instrument that creates ideal conditions for sound

to travel. The design of a guitar is based on several physics

concepts that can be utilized to produce an instrument of the

highest quality.

[21] Ref. 19.

[22] Ref. 19.

[23] Johnston, J. E. "The Theory Behind Free Plate Tuning Using

Chladni

Mode Patterns." Jack Johnston Guitar Maker. 27 Feb. 2011.

Web. 01

Mar.

2012.

<http://jackjohnstonguitarmaker.com/TheTheoryBehindFreePlat

eTuni

ngUsingChladniModePatterns.aspx>.

[24] Ref. 19.

[25] Ref. 23.

[26] Ref. 19.

[27] Ref. 23.

[28] Perlmeter, A, "Redesigning the Guitar." Science News 98.8/9

(1970):

180-81. JSTOR. Web. 15 Feb. 2012.

[29] Ref. 28.

[30] Ref. 28.

REFERENCES

[1] Kasha, M, "A New Look at The History of the Classic Guitar",

Guitar

Review, 30 Aug., 1968, pp.3-12.

[2] Tyler, J, “The Renaissance Guitar 1500-1600” Early Music, Vol. 3,

No.

4, Oct., 1975, pp. 341-347

[3] Guy, P, "A Brief History of the Guitar." Guitar Handbook. Paul

Guy

Guitars, 2001. Web. 27 Feb.

2012.

<http://www.guyguitars.com/eng/handbook/BriefHistory.html>.

[4] Wolfe, J, "How Does a Guitar Work?" How a Guitar Works.

University

New South Whales. Web. 29 Feb.

2012.

<http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/music/guitar/guitarintro.html>.

[5] Ref. 4

[6] Hewitt, Paul G, Conceptual Physics, 11th ed. San Francisco:

Pearson

Addison Wesley, 2010.

[7] Ref. 6.

[8] Parker, B. R, Good Vibrations: The Physics of Music.

Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins UP, 2009. pp. 160-163

[9] Just Strings, Web. 29 Feb. 2012. <http://www.juststrings.com>.

[10] Ref. 8.

[11] Ref. 6.

[12] Ref. 6.

[13] Ref. 4.

[14] Ref. 6.

[15] Hokin, S. "The Physics of Everyday Stuff: The Guitar."

Bsharp.org.

2012. Web. 29 Feb. 2012.

<http://www.bsharp.org/physics/guitar>.

[15] Ref. 3.

[16] Usher, T. "The Spanish Guitar in the Nineteenth and

Twentieth

Centuries." The Galpin Society Journal 9 (1956): 5-36.

JSTOR. Web.

15 Feb. 2012.

[17] Ref. 3.

[18] Eendebak, B, "The Soundboard." Design of a Classical

Guitar.

2011. Web. 01 Mar.

2012.

<http://www.designofaclassicalguitar.com/soundboard.php>.

[19] Wolfe, J, "How Does a Guitar Work?" Chladni Patterns for

Guitar

Plates. University New South Whales. Web. 29 Feb.

2012.

<http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/music/guitar/guitarintro.html>.

[20] Ref. 19.

April 27, 2012

American University, Washington, DC

12th Annual New Millennium Conference

86