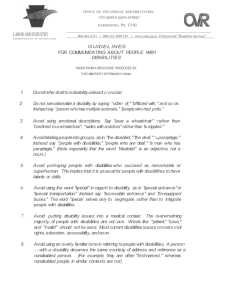

Major hazards and people with disabilities

advertisement