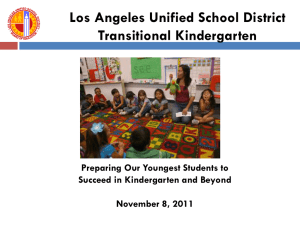

Kindergarten Learning Experiences

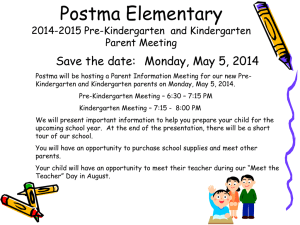

advertisement