My Directed Self-Placement Essay

advertisement

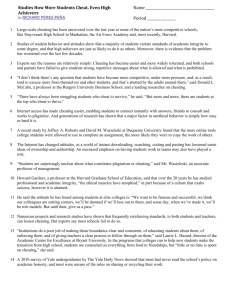

In today’s competitive educational setting, cheating is becoming more and more prevalent. In the New York Magazine article, “Cheating Upwards,” Robert Kolker takes a whack at revealing some of the motivation that students have to making attempts to cheat. I feel that many of the explanations of why students cheat all point back to the same two motivators; success and efficiency. The main instance of cheating described in this article was the case at Stuyvesant, an extremely competitive and renowned high school in New York. A student, blanketed by the pressures of success and placed in a high pressure testing situation, felt a heavy weight to succeed. He was also feeling sympathetic to his peers, and knowing that they also placed great stress on this test, had a desire to help them. He had also arranged for a little extra assistance on future examinations in his weaker subjects. He barely had to put out any extra effort and received a benefit from it as well. It seemed to be a win-win situation, and, to him, was worth the risk. By arranging the answer sharing network and putting the tactics into place, he completed his examination then sought out to supplying his peers with the answers. It was a chain reaction. By increasing their test scores, they could also increase their grades, increasing their GPAs, giving them a competitive edge. This competitive edge could ultimately increase their opportunities of being accepted into better universities, not to mention making their high school look good. Students also believe, the better the university, the better the job placement and the higher the chance of success. At a certain point, some students are willing to do whatever it takes to sharpen their competitive edge. But at what point does it become too much? Students consider many things when carrying the pressure to succeed on their backs. If success is attained, does anyone care what it took to get there? What difference does it make if I follow my set of morals or just make compromises along the way? When teens are so easily swayed by the opinions of others and have only dreams set in their spotlights, it is critical that they are reminded of what is truly right, before they compromise what truly matters for temporary shortcuts. Eric Anderman, a professor of educational psychology at Ohio State University also commented on the pressure to succeed. There is an increasing temptation to cheat with the enlarging emphasis placed on testing importance. He stated that large tests can determine your acceptance into colleges, which, in a competitive and globalized world, can stem to success. School becomes more of a place to demonstrate your intelligence based on numbers rather than being seen as a place to learn. He also said, “If everything is always high-stakes, you’re going to create an environment conductive to cheating.” Students feel a struggle to stay on top in order to succeed and are sometimes willing to compromise their integrity to do so. In many cases, students are eager and willing to sacrifice their integrity out of laziness. They think it is much easier and more desirable to slack off and look for the easiest way and cheat whenever possible versus putting in ample amounts of effort to insure success. High school is a time where people are obviously susceptible to peer pressure. Just like competing towards success academically, teens also want to compete to become more popular. From personal experiences, I have witnessed situations in which teenagers are encouraged by their peers to attempt stunts that are totally against their set of morals. But they attempt anyways, despite what their conscious has to say. They are willing to compromise what they truly believe is right to gain attention and an upper hand in the social scene. They’d be willing to try the bigger jump on their ATVs, order the spiciest buffalo wings on the menu, throw parties when their parents are out of town, all in attempt to become “top dog” and impress their peers. Competing towards popularity is just another instance in which success has a prominent force. Dan Ariely, a Duke social scientist, has also started to cracking down into the reason behind teens’ impulse to cheat. Ariely stated that the ventral stratium and obiofrontal cortex, developed after puberty, tend to be more dominate over the lateral prefrontal cortex, which may not completely develop until early adulthood. This would explain why teenagers would be willing to take the risk and seek out the sensations that come with cheating rather than controlling their impulses and doing what is ethically and morally just. Ariely stated,”There is right and wrong, and there is what people around us tell us is right and wrong. The people around are often more powerful.” Students have also never been as well equipped to cheat on examinations as they are now. Cell phones with access to texting, networking, and emailing make communication a breeze, whether it is for the right or wrong reasons. Also, many standardized tests are multiple choice, and offer no variance to having the correct or incorrect answers. It’s black or white, you either you select the right answer or the wrong one. Even though it is easier to grade large numbers of multiple choice tests, it can also be easier, and more efficient to share a large number of answers on a large number of these tests, as compared to tests with short answer or essay style questions. Cheating is very tempting to risk taking teens. It seems more effective and efficient to simply have one person spend time studying than for everyone to put in the hours. As long as one person knows the correct answers, why wouldn’t they want to share with everyone? The only goal in mind is success. Integrity seems very distant and unimportant, and they just want to reap the benefits of here and now instead of sowing the seeds. They prefer seeking instant satisfaction, not realizing the growing worth of investments. Robert Kolker does a sufficient job in trying to explain the drive behind cheating, everything rooting back to their desire for efficiency and success.