What are probing questions?

Framing Consultancy

Guide to Clarifying & Probing Questions

Making the distinction between clarifying questions and probing questions can be very difficult for people working with protocols. It can also be difficult to make the distinction between probing

questions and recommendations for action. Following are some basic distinctions.

What are clarifying questions?

Clarifying questions are simple questions of fact. They clarify the dilemma and provide the nuts and bolts so that the Consultancy Group can ask good probing questions and provide useful feedback later in the protocol. Clarifying questions are for the participants in the Consultancy Group, and should not go beyond the borders of the presenter’s dilemma. They have brief, factual answers, and don’t provide any

“food for thought” for the presenter. The litmus test for clarifying questions is “Does the presenter have to stop and think before s/he answers the question?” If so, it’s almost certainly a probing question, not a clarifying question.

Some examples of clarifying questions include:

How much time does this project take?

How were students grouped?

What resources did students have available to them?

How many times did you try that particular strategy?

Who has been involved in the project?

What are probing questions?

Probing Questions are intended to help the presenter think more deeply about the issue at hand. If a probing question doesn’t have that effect, it is either a clarifying question or a recommendation for action with an upward inflection at the end. If you find yourself saying “Do you think you should…?” you’ve gone beyond probing questions to a recommendation for action. The presenter often doesn’t have a ready answer for a genuinely probing question.

Effective probing questions:

¶ Are general and widely used

¶ Are fairly brief

¶ Avoid yes/no responses

¶ Don’t place blame or judgment on anyone

¶ Allow for multiple responses

¶ Help create a paradigm shift

¶ Encourage taking a different perspective

¶ Empower the person with the dilemma to solve his/her own problem, rather than deferring to someone else with greater or different expertise

¶ Elicit a slow response/require “think time”

¶ Move thinking from reaction to reflection

Developed by Gene Thompson-Grove, Edorah Frazer, Faith Dunne, and further revised by Edorah Frazer

Framing Consultancy

Guide to Clarifying & Probing Questions

How do I develop probing questions?

Probing questions are hard to create productively and spontaneously. Here are some suggestions for developing probing questions:

¶ Check to see if you have a ‘right” answer in mind for the question. If you do, delete the judgment from the question, or don’t ask it.

¶ Refer to the presenter’s original question/focus point. What did s/he as for help with? Check your probing questions for relevance.

¶ Check to see if your probing question reflects your own agenda. If so, return to the presenter’s agenda.

¶ Sometimes a simple “Why…?” asked as an advocate for the presenter’s success can be very effective, as can asking several “Why…?” questions in a row.

¶ Try using verbs: What do you fear? What do you want? What do you assume? What do you

expect?

¶ Think about concentric circles of comfort, risk and danger. Use these as a barometer. Don’t avoid risk, but don’t push the presenter into the danger zone, either.

Try the following questions and question stems for crafting probing questions. (Note: Some are from

Charlotte Danielson’s work, Pathwise, referred to as mediational questions.)

¶ Why do you think this might be the case?

¶ What would have to change in order to…?

¶ What do you feel is right in your heart?

¶ What does your gut tell you?

¶ What’s your greatest wish?

¶ What’s another way you might…

¶ What would it look like if…

¶ What do you think might happen if…?

¶ How is …different from…

¶ What sort of an impact do you think …?

¶ What criteria did you use to…?

¶ When have you done/experienced something like this before?

¶ What might you see happening in your classroom if you …?

¶ How did you decide/determine/conclude…?

¶ What’s your hunch about…?

¶ What was your intention when you…?

¶ What do you assume to be true about…?

¶ What is the connection between … and…?

What if the opposite were true? Then what?

¶ How might your assumptions about … have influenced your thinking about …?

¶ Why is this such a dilemma for you? What bothers you most about it?

Developed by Gene Thompson-Grove, Edorah Frazer, Faith Dunne, and further revised by Edorah Frazer

Framing Consultancy

Guide to Clarifying & Probing Questions

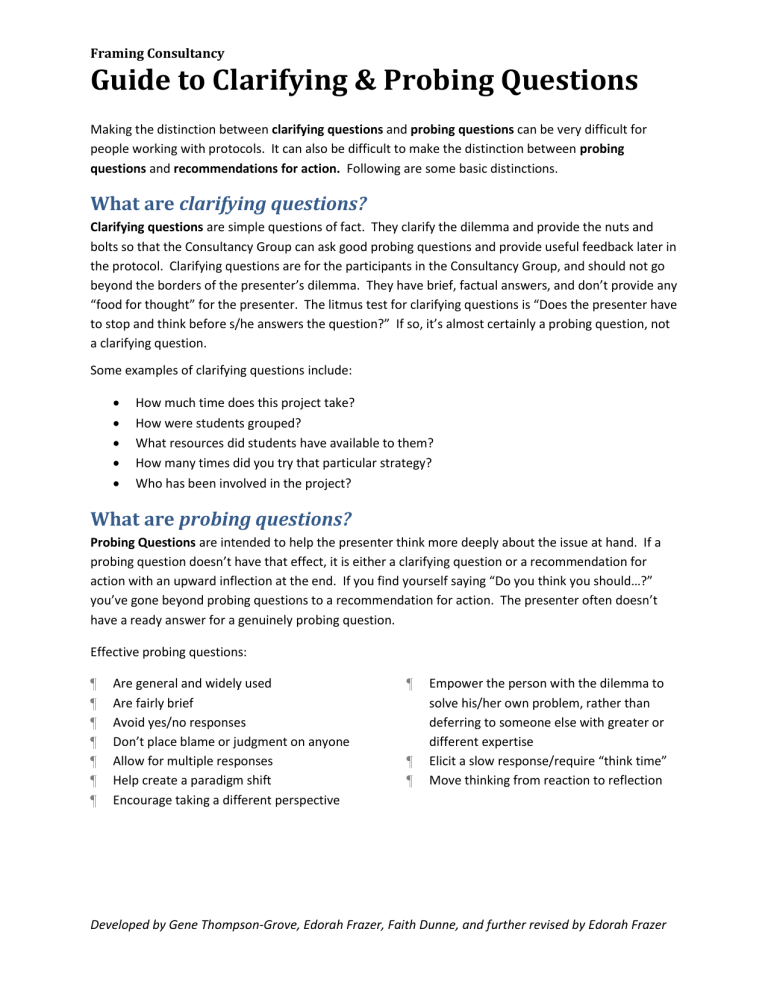

Example of probing questions in a Consultancy

Think of probing questions as being on a continuum, from recommendation to action to most effective

probing question. For example, consider these questions from an actual Consultancy:

The presenter is trying to figure out why the strongest math students in her class weren’t buying into and doing their best work on what she considered to be interesting math problems of the week.

Avoid!

Recommendation for action posing as a question!

What might happen if students used the rubric to assess their own work?

Good Better!

General probing question related to dilemma

Probing question, more precise to the presenter’s dilemma

What do the students think is an interesting math problem?

What would have to change to have students work more for themselves and buy into math problems?

Other examples of probing questions from the Consultancy on students buying into math problems:

¶ How might your own comfort level with the material influence your choice of instructional strategies?

¶ How would students describe “high quality work?”

¶ You’ve said that this student’s work lacks focus. What makes you say that?

¶ How do you think the students involved see this issue?

¶ How have your perspectives on students’ behavior in the past influenced how you structured the activity?

¶ What might happen if you involved teachers from other departments in planning this unit?

¶ What would understanding of this mathematical concept look like? How would you know that students “get it?”

¶ What bothers you about allowing students to create their own study questions?

¶ Why do you think that parents might have been unclear or confused about the expected outcomes of this unit?

¶ What was your intention when you asked the students to oversee the group activity in this lesson?

¶ What evidence do you see in student work that they are getting better at reaching substantiated conclusions?

¶ How might your expectations for students have influenced their work on this assignment?

Developed by Gene Thompson-Grove, Edorah Frazer, Faith Dunne, and further revised by Edorah Frazer