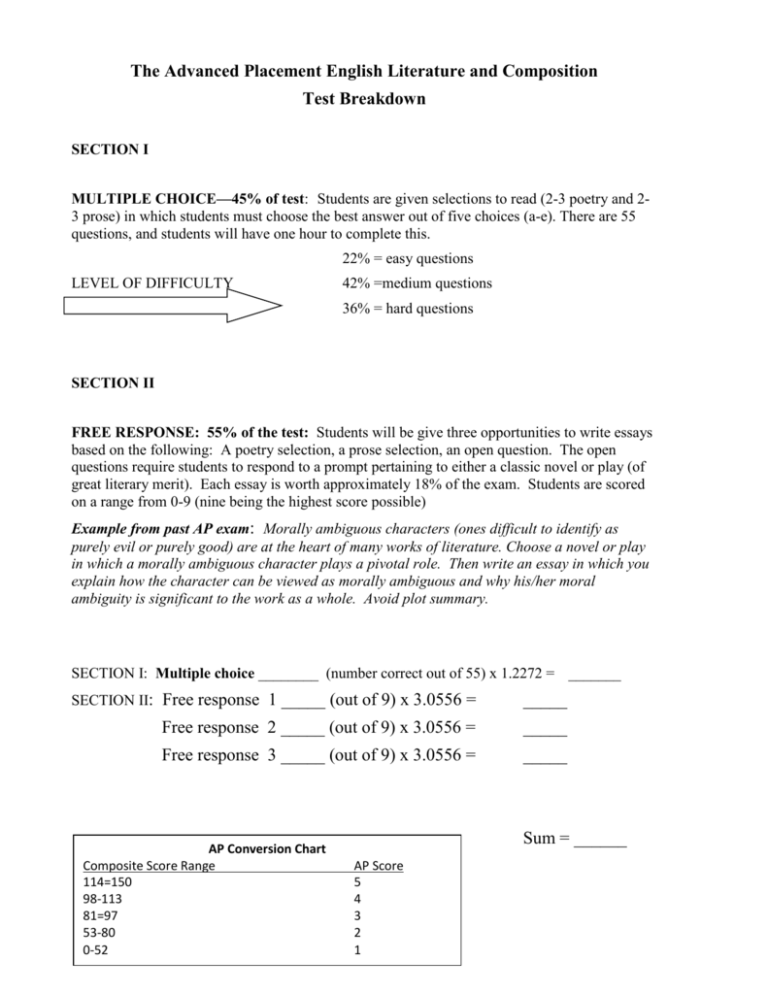

The Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition

Test Breakdown

SECTION I

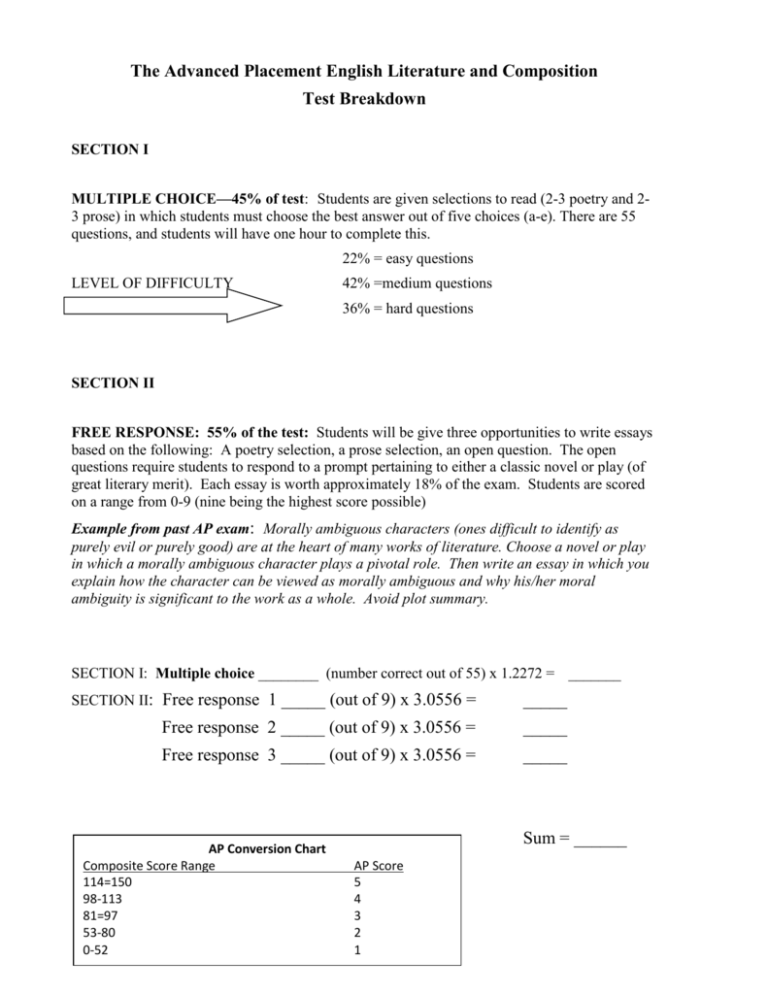

MULTIPLE CHOICE—45% of test: Students are given selections to read (2-3 poetry and 23 prose) in which students must choose the best answer out of five choices (a-e). There are 55

questions, and students will have one hour to complete this.

22% = easy questions

LEVEL OF DIFFICULTY

42% =medium questions

36% = hard questions

SECTION II

FREE RESPONSE: 55% of the test: Students will be give three opportunities to write essays

based on the following: A poetry selection, a prose selection, an open question. The open

questions require students to respond to a prompt pertaining to either a classic novel or play (of

great literary merit). Each essay is worth approximately 18% of the exam. Students are scored

on a range from 0-9 (nine being the highest score possible)

Example from past AP exam: Morally ambiguous characters (ones difficult to identify as

purely evil or purely good) are at the heart of many works of literature. Choose a novel or play

in which a morally ambiguous character plays a pivotal role. Then write an essay in which you

explain how the character can be viewed as morally ambiguous and why his/her moral

ambiguity is significant to the work as a whole. Avoid plot summary.

SECTION I: Multiple choice ________ (number correct out of 55) x 1.2272 = _______

SECTION II: Free response 1 _____ (out of 9) x 3.0556 =

_____

Free response 2 _____ (out of 9) x 3.0556 =

_____

Free response 3 _____ (out of 9) x 3.0556 =

_____

AP Conversion Chart

Composite Score Range

114=150

98-113

1 81=97

53-80

0-52

Sum = ______

AP Score

5

4

3

2

1

Flannerby Barp for Nall”

Nall was so plamper. She was larping to the flannerby with Charkle. She would

grunk a flannerby barp so she could crooch out carples. Charkle lanted her gib out

the nep. “Parps, Charkle,” jibbed Nall plamperly. “Now we can crooch out carples

together!” pifed Charkle trigly.

Pop Quiz

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Who are the characters in this story?

What do we know about Nall?

Why did she want to grunk a flannerby barp?

Where did Charkle lant her gib?

Why was Charkle so excited?

.

ANALYSIS

The process of analysis involves breaking something into its component parts, examining those

parts, and through such an examination, coming to a better understanding of the whole. In

literature it is asking what something means and how that meaning is constructed. Analysis is

one of the most common human activities, and is the sort of thinking one is asked to do most

often in school, work, and in life. Essentially, there are five steps to analysis:

1.

SUSPEND JUDGMENT: Avoid either or thinking. Do not oversimplify. For example,

when people walk out of a theater after having seen a movie, they will state that they

liked the movie or that they didn’t. Such comments are emotional, personal reactions

and do not say much that is significant because they are so general. The above

judgment says more about a person’s tastes, preferences, biases, and experiences than

about the movie and its qualities. Many people base their judgment of a work of

literature on their personal reactions to it rather than its intrinsic qualities. In reading a

student must go beyond “what it says” to “what it means.” Seek to understand the

subject he/she is analyzing before moving to a judgment about it.

2.

MAKE THE IMPLICIT EXPLICIT: Look beyond the surface. For example, instead of

merely looking at a magazine ad, ask yourself not what is in it, but what is it really

about. “Why” is an essential question to keep in mind? Why did the advertiser choose

this particular image or set of images? What was his purpose and what results did he

hope to achieve? Now you are making inferences.

3.

DEFINE SIGNIFICANT PARTS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIPS: When analyzing

literature, divide it into its various parts, elements, or strategies. Consider how these

parts are related not only to each other but also to the whole. The idea is not only to

examine the parts but also to understand how they give it life, meaning, style, etc.

2

4.

LOOK FOR PATTERNS: Patterns may come in such forms as repetition or

resemblance of words, constructions, or ideas; shifts in time or tense; a change in point

of view; a move from general to specific or vice versa; a repeated use of imagery;

and/or patterns in diction or syntax.

KEEP REFORMULATING QUESTIONS AND EXPLANATIONS: What details seem

significant? Why? What is the significance of that detail? What does it mean on a

literal level? A metaphorical level? What else might it mean? How do the details fit

together? What do they have in common? How do they differ? What might a certain

pattern of details indicate? What else might this same pattern of details mean? What

ideas might the author be attempting to convey? What details do not seem to fit?

5.

Steps to Close Reading

An explication of text: means to unfold, to fold out, or to make clear the meaning. This is a finely

detailed, very specific examination of a short poem or short selected passage from a longer work, in

order to find the focus or design of the work, either in its entirety in the case of the shorter poem or, in the

case of the selected passage (the longer work of which it is a part). To this end "close" reading calls

attention to all dynamic tensions, polarities, or problems in the imagery, style, literal content, diction, etc.

Close Reading or Explication operates on the premise that literature, as artifice, will be more fully

understood and appreciated to the extent that the nature and interrelations of its parts are perceived, and

that that understanding will take the form of insight into the theme of the work in question. This kind of

work must be done before you can begin to appropriate any theoretical or specific literary approach.

Follow these steps before you begin writing. These are pre-writing steps,

procedures to follow, questions to consider before you commence actual writing.

In selecting one passage from a short story, poem, or novel, limit your selection to a short paragraph (4-5

sentences), but certainly no more than one paragraph. When one passage, scene, or chapter of a larger

work is the subject for explication, that explication will show how its focused-upon subject serves as a

macrocosm of the entire work—a means of finding in a small sample patterns which fit the whole work.

If you follow these steps to literary awareness, you will find a new and exciting

world. Do not be concerned if you do not have all the answers to the questions in this section. Keep

asking questions; keep your intellectual eyes open to new possibilities.

1. Figurative Language. Examine the passage carefully for similes, images, metaphors, and

2.

3.

3

symbols. Identify any and all. List implications and suggested meanings as well as denotations.

What visual insights does each word give? Look for mutiple meanings and overlapping of

meaning. Look for repetitions, for oppositions.

Diction. This section is closely connected with the section above. Diction, with its emphasis on

words, provides the crux of the explication. The dictionary will illuminate new connotations and

new denotations of a word. Look at all the meanings of the key words. Look up the etymology of

the words. How have they changed? The words will begin to take on various meanings. Be

careful to always check back to the text, keeping meaning contextually sound. Do not assume

you know the depth or complexity of meaning at first glance. Rely on the dictionary.

Literal content: this should be done as succinctly as possible. Briefly describe the sketetal

contents of the passage in one or two sentences. Answer the journalist's questions (Who? What?

When? Where? Why?) in order to establish character/s, plot, and setting as it relates to this

passage. What is the context for this passage?

4. Structure. Divide the passage into the more obvious sections (stages of argument, discussion,

or action). What is the interrelation of these units? How do they develop? Again, what can you

postulate regarding a controlling design for the work at this point? If the work is a poem, identify

the poetic structure and note the variations within that structure.

5. Style. Look for any significant aspects of style—parallel constructions, antithesis, etc. Look for

patterns, polarities, and problems. Periodic sentences, clause structures? Polysyndeton etc.?

And reexamine all postulates, adding any new ones that occur to you. Look for alliteration,

internal rhymes and other such poetic devices which are often used in prose as well as in poetry. .

6. Characterization. What insight does this passage now give into specific characters as they

develop through the work? Is there a persona in this passage? Any allusions to other literary

characters? To other literary works that might suggest a perspective. Look for a pattern of

metaphoric language to give added insight into their motives and feelings which are not

verbalized.

7. Tone. What is the tone of the passage? How does it elucidate the entire passage? Is the tone

one of irony? Sentimental? Serious? Humorous? Ironic?

8. Assessment. This step is not to suggest a reduction; rather, a "close reading" or explication

should enable you to problematize and expand your understanding of the text. Ask what insight

the passage gives into the work as a whole. How does it relate to themes, ideas, larger actions in

other parts of the work?

9. Context: If your text is part of a larger whole, make brief reference to its position in the whole; if it

is a short work, say, a poem, refer it to other works in its author's canon, perhaps chronologically,

but also thematically. Do this expeditiously.

10. Theme: A theme is not to be confused with thesis; the theme or more properly themes of a work

of literature is its broadest, most pervasive concern, and it is contained in a complex combination

of elements. In contrast to a thesis, which is usually expressed in a single, arugumentative,

declarative sentence and is characteristic of expository prose rather than creative literature, a

theme is not a statement; rather, it often is expressed in a single word or a phrase, such as

"love," "illusion versus reality," or "the tyranny of circumstance." Generally, the theme of a work is

never "right" or "wrong." There can be virtually as many themes as there are readers, for

essentially the concept of theme refers to the emotion and insight which results from the

experience of reading a work of literature.

Everything you say about the theme must be supported by the brief quotations from the text.Your

argument and proof must be convincing. And that, finally, is what explication is about:

marshaling the elements of a work of literature in such a way as to be convincing. Your

approach must adhere to the elements of ideas, concepts, and language inherent in the work

itself. Remember to avoid phrases and thinking which are expressed in the statement, "what I

got out of it was. . . ."

11. Thesis: Do not try to write your thesis until you have finished all 12 steps. The thesis should take

the form, of course, of an assertion about the meaning and function of the text which is your

subject. It must be something which you can argue for and prove in your essay.

Whenever reading a passage, a poem, an essay, etc. it is important to annotate (take notes,

highlight, comment, etc.) I will provide you with an example of an annotation.

Closely read “Independence” and annotate before the class discussion.

Chuang Tzu was one day fishing, when the Prince of Ch’u sent two high officials to interview

him, saying that his Highness would be glad of Chuang Tzu’s assistance in the administration of his

government. The latter quietly fished on, and without looking round, replied, “I have heard that in the

State of Ch’u there is a sacred tortoise, which has been dead three thousand years, and which the prince

keeps packed up in a box on the altar in his ancestral shrine. Now do you think that tortoise would rather

be dead and have its remains thus honoured, or be alive and wagging its tail in the mud? The two

officials answered that no doubt it would rather be alive and wagging its tail in the mud; whereupon

Chuang Tzu cried out, “Begone! I too elect to remain wagging my tail in the mud!”

4

Introductory Lessons: AP Lit and Comp

Approaching Literature

There are many specific strategies to approaching a literary text and writing about it. Some of

these strategies we will discuss in detail, and I will be recommending different strategies for you

as this class goes on. We want to start, though, by suggesting a straightforward three-step

approach that will give you a way into any written text:

Experience

When we experience literature, we respond to it subjectively, personally, emotionally. We bring

to it our own life experiences and knowledge.

Analysis

Here, you move from feeling to thinking. The key is observation: No detail is unimportant, so

notice, notice, notice. What about language and structure? What connections or patterns emerge?

What inferences might you draw from these connections?

Extension

At this point, you have arrived at an interpretation. Sometimes that is all you will need to do. But

sometimes you will be able to extend your interpretation from the world of the poem to the real

world. This type of extension may involve examination of the background of the author, research

into the historical context of the work, or application of the ideas in the piece to life in general.

Read the poem first (next page) then revisit the next categories.

Experience:

A fairly grisly scene: boy cutting wood, the saw slips, and he cuts his hand-despite the

doctor's efforts the boy dies-everyone goes back to work-end of story

Might think people in the poem are heartless and cold-might remind you of something

you've read about or even experienced

Live in the city-might feel far removed from rural Vermont-spent time on the farmmight have a more familiar ring

But even at this first step, you cannot help but notice the language and details. YOU'VE

ENTERED THE WORLD OF THE POEM!

5

Analysis:

Now move from feeling to thinking. The key is observation. No detail is unimportant.

What do you notice about the language and structure of the poem? What connections

or patterns emerge? What inferences might you draw from these connections? Is

something stands out from the rest of the poem, you probably want to ask why. You

ARE reading between the lines-what is indirectly expressed through figurative

language and other poetic techniques.

6

Buzz saw-an animal that "snarled and rattled," a description repeated three times

before the saw "leaped out at the boy's hand, or seemed to leap" (I. 16). This

personification suggests that it wasn't an accident, that the saw was a predator

intending to hurt the boy. Then Frost gives us a description of the natural beauty of the

landscape-the mountain ranges and the sunset. Why would Frost juxtapose idea of

the saw being a vicious animal with the beauty of the countryside. Maybe he is saying

that nature has two sides, violent and peaceful, predatory and nourishing? What do you

think?

Notice the third-person point of view, except in line 10 when the speaker says that he

wishes they would have "called it a day" and given the boy a half hour away from his

work. Why shift perspective here? Was it Frost's way of anticipating the accident to

come? Maybe they give the poem a bit of soul, express some regret, or temper the cold

practicality of the final lines.

"Out, Out--," by Robert Frost

The buzz-saw snarled and rattled in the yard

And made dust and dropped stove-length sticks of wood,

Sweet-scented stuff when the breeze drew across it.

And from there those that lifted eyes could count

Five mountain ranges one behind the other

Under the sunset far into Vermont.

And the saw snarled and rattled, snarled and rattled,

As it ran light, or had to bear a load.

And nothing happened: day was all but done.

Call it a day, I wish they might have said

To please the boy by giving him the half hour

That a boy counts so much when saved from work.

His sister stood beside them in her apron

To tell them "Supper." At that word, the saw,

As if to prove saws knew what supper meant,

Leaped out at the boy's hand, or seemed to leap He must have given the hand. However it was,

Neither refused the meeting. But the hand!

The boy's first outcry was a rueful laugh,

As he swung toward them holding up the hand

Half in appeal, but half as if to keep

The life from spilling. Then the boy sawall Since he was old enough to know, big boy

Doing a man's work, though a child at heart He saw all spoileds''Don't let him cut my hand off"The doctor, when he comes. Don't let him, sister!"

So. But the hand was gone already.

The doctor put him in the dark of ether.

He lay and puffed his lips out with his breath.

And then - the watcher at his pulse took fright.

No one believed. They listened at his heart.

Little - less - nothing! - and that ended it.

No more to build on there. And they, since they

Were not the one dead, turned to their affairs.

7

The Writer's Craft-Close Reading-The Elements of Style

The point of close reading is to go beyond merely summarizing a work to figuring out how a writer's stylistic choices

convey the work's message or meaning. Once you begin to analyze literature closely, you will see how all ofthe parts of

a piece of literature work together, from the structure of the piece down to individual word choices. The following is a

brief introduction to the essential elements of style. Understanding these terms and concepts will give you things to be

on the lookout for as you close-read, as well as vocabulary to help you describe what you see. Most of these terms are

not new to you, but the following will serve to refresh your memory. If you need more explanation or examples, they

are available in the back of your Bedford text and always, of course, in many on-line sources.

Diction

Authors choose their words carefully to convey precise meanings. We call these word choices the author's diction. A

word can have more than one dictionary definition, or denotation, so when you analyze diction, you must consider all of

a word's possible meanings. If the words have meanings or associations beyond the dictionary definitions, their

connotations, you should ask how those relate to meaning. Sometimes a word's connotations will reveal another layer

of meaning; sometimes they will affect the tone, as in the case of formal or informal diction, which is sometimes called

slang, or colloquia" language. Diction can also be abstract or concrete. Let's look at an example of diction from the

third stanza of Housman's poem "To an Athlete Dying Young":

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory

does not stay

And early though the

laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

In the third line, Housman plays with the multiple denotations of the word laurel, which is both a small evergreen tree,

and an honor or accolade. Housman is using these multiple denotations to establish a paradox. Though the laurel that

represents fame is evergreen, fame itself is fleeting, even more fleeting than the rosy bloom of youth.

Figurative Language

Language that is not literal is called figurative, as in a figure of speech. Sometimes this kind of language is called

metaphorical because it explains or expands on an idea by comparing it to something else. The comparison can be

explicit, as in the case of a simile, which makes a comparison using like or as; or it can be an implied comparison, as

in the case of a metaphor. Personification is a figure of speech in which an object or animal is given human

characteristics. An analogy is a figure of speech that usually helps explain something unfamiliar or complicated by

comparing it to something familiar or simple.

8

When a metaphor is extended over several lines in a work, it's called an extended metaphor; a conceit (or metaphysical

conceit) denotes a fairly elaborate figure of speech, especially an extended comparison involving unlikely metaphors,

similes, imagery, hyperbole, and oxymora. Other forms of figurative language include overstatement (or hyperbole),

understatement, paradox (a statement that seems contradictory but actually reveals a surprising truth), and irony.

There are a few different types of irony, but verbal irony is the most common. It occurs when a speaker says one thing

but really means something else, or when there is a noticeable incongruity between what is expected and what is said.

Imagery

Imagery is the verbal expression of a sensory experience and can appeal to any of the five senses. Sometimes

imagery depends on very concrete language-that is, descriptions of how things look, feel, sound, smell, or taste.

In considering imagery, look carefully at how the sense impressions are created. Also pay attention to patterns of

images that are repeated throughout a work. Often writers use figurative language to make their descriptions

even more vivid. Look at this description passage from Willa Cather's My Antonia:

Queer little red bugs came out and moved in slow squadrons around me. Their backs were

polished vermilion, with black spots.

The imagery tells us that these are little red bugs with black spots, but consider what is added with the

words "squadrons" and "vermilion," both figurative descriptions.

Syntax

Syntax is the arrangement of words into phrases, clauses, and sentences. When we read closely, we consider

whether the sentences in a work are long, or short, simple or complex. The sentence might be cumulative,

beginning with an independent clause and followed by subordinate clauses or phrases that add detail; or

periodic, beginning with subordinate clauses or phrases that build toward the main clause. The word order can

be the traditional subject-verb- object order or inverted (e.g., verb-subject-object or object-subject-verb). You

might also look at syntactic patterns, such as several long sentences followed by a short sentence. Housman

uses inversion in several places in his poem, perhaps to ensure the rhyme scheme but also to emphasize a

point. When he writes, "And home we brought you shoulder-high," the shift in expected word order ("We brought

you home") emphasizes "home," a word emphasized more than once in the poem.

Tone and Mood

Tone reflects the speaker's attitude toward the subject of the work. Mood is the feeling the reader experiences as

a result of the tone. Tone and mood provide the emotional coloring of a work and are created by the writer's

stylistic choices. When you describe the tone and mood of a work, try to use at least two precise words, rather

than words that are vague and general, such as happy, sad, or different. What is most important is that you

consider the style elements that went into creating the tone. (I will also supply you with a tone word list-soon!)

9

Questions for Close Reading of Text-The Elements of Style

Diction

Which of the important words (verbs, nouns, adjectives, and adverbs) in the

poem or

passage are general and abstract, and which are specific and concrete?

Are the important words formal, informal, colloquial, or slang?

Are there words with strong connotations, words we might refer to as "loaded"?

Figurative Language

Are some words not literal but figurative, creating figures of speech such as

metaphors, similes, and personification?

Imagery

Are the images-the parts of the passage we experience with our five sensesconcrete, or do they depend on figurative language to come alive?

Syntax

What is the order of the words in the sentences? Are they in the usual subject-verbobject order, or are they inverted?

Which is more prevalent in the passage, nouns or verbs?

What are the sentences like? Do their meanings build periodically or cumulatively?

How do the sentences connect their words, phrases, and clauses?

How is the poem or passage organized? Is it chronological? Does it move from

concrete to abstract or vice versa? Or does it follow some other pattern?

10

Exercise 1

Read Housman's "To an Athlete Dying Young" and working with a partner, analyze the poem by applying the

preceding list of questions to the poem. Be sure to address each question. Be prepared to present your findings to

the class.

To An Athlete Dying Young-A. E. Housman

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

To-day, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay,

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.

And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strength less dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl's.

11

Exercise 2

Read this passage from Eudora Welty's short story "Old Mr. Marblehall," and using the preceding list of

questions for analysis, prepare a response for our next class meeting. You do not have to type this

response.

There is Mr. Marblehall's ancestral home. It's not so wonderfully large-it has only four columns-but you

always look toward it, the way you always glance into tunnels and see nothing. The river is after it now,

and the little black garden has assuredly crumbled away, but the box maze is there on the edge like a

trap, to confound the Mississippi River. Deep in the red wall waits the front door-it weighs such a lot, it

is perfectly solid, all one piece, black mahogany .... And you see-one of them is always going in it.

There is a knocker shaped like a gasping fish on the door. You have every reason in the world to

imagine the inside is dark, with old things about. There's many a big, deathly-looking tapestry, wrinkling

and thin, many a sofa shaped like an S. Brocades as tall as the wicked queens in Italian tales stand

gathered before the windows. Everything is

draped and hooded and shaded, of course, unaffectionate but close. Such rosy lamps! The only sound

would

be a breath against the prisms, a stirring of the chandelier. It's like old eyelids, the house with one of its

shutters, in careful working order, slowly opening outward.

Place Response Below: _____________________________________________________________________________ _

12

Purpose: It seems that almost everything on the AP exam is motivated by purpose. That is,

why did the author choose the point of view, tone, rhetorical strategies, stylistic devices, etc.?

Basically, these choices are the ones that allow the author to achieve his purpose.

To move from gaining in-depth insight, providing apt and specific support, and finally to discussing

purpose, effect, or reason for strategies used by an author, many students can manage the first and

the second but falter when it comes to the last concept. Here are some phrases that may help

students move to the higher level of purpose. Hint: Usually the purpose can be indicated as the

“VERB” indicating what the author or the speaker does.

For example, in The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne’s use of symbols, allows him to convey the

contradictions and hypocrisy inherent in Puritan society (Do as I say, not as I do). The letter itself is

meant to be a symbol of shame, but instead it becomes a powerful symbol of identity to Hester. The

letter’s meaning shifts as time passes. Originally intended to mark Hester as an adulterer, the “A”

eventually comes to stand for “Able

PURPOSE WORDS!

--- serves to

--- infers

--- adds to

-- translates to

--- enriches the

--- proposes

--- shows

--- reflects

--- demonstrates

--- contributes to

--- suggests

--- lets the reader know

--- illustrates

--- employs

--- emphasizes

--- foreshadows

--- reveals

--- allows the reader

--- portrays

--- stresses the

--- exemplifies

--- is supported by

--- explains

---completes the

--- elaborates

--- characterizes

--- conveys

--- implies

13

“Storm Warnings” – Adrienne Rich

The glass has been falling all the afternoon,

And knowing better than the instrument

What winds are walking overhead, what zone

Of gray unrest is moving across the land,

5

I leave the book upon a pillowed chair

And walk from window to closed window, watching Boughs strain against the sky.

And think again, as often when the air

Moves inward toward a silent core of waiting,

10

How with a single purpose time has traveled

By secret currents of the undiscerned

Into this polar realm. Weather abroad

And weather in the heart alike come on

What seems to be the overall

purpose of the vivid imagery

the poet is using?

Regardless of prediction.

15

Between foreseeing and averting change

Lies all the mastery of elements which

clocks and weatherglasses cannot alter.

Time in the hand is not control of time,

Nor shattered fragments of an instrument

20

A proof against the wind; the wind will rise,

We can only close the shutters.

I draw the curtains as the sky goes black

And set a match to candles sheathed in glass

Against the keyhole draught, the insistent whine of weather through the unsealed aperture. Ths is

our sole defense against the

Season; These are the things we have learned

to do who live in troubled regions.

14

Elements of VOICE

Voice is the characteristic speech and thought patterns of a first-person narrator; a persona.

Voice is the sum of all a writer becomes on the page. It is the concerns and themes that most

occupy a writer. It allows for a breadth of vision. It consists of Style / Language / Syntax

/Imagery / Authority / Paragraphs / Point of View / Tone / Attitude and Register. Voice is the

author’s style, the quality that makes his or her writing unique, and which conveys the author’s

attitude, personality, and character; or Voice is the characteristic speech and thought patterns

of a first-person narrator; a persona.

Because voice has so much to do with the reader's experience of a work of literature, it is one

of the most important elements of a piece of writing.

Make a list of the characteristics of writing that indicate strong voice.

It shows the writer's personality

It sounds different from everyone else's

It contains feelings and emotions

The words come to life

It comes from the heart

There are many examples of strong voice in literature. Some of these are:

Huck Finn in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

Nick in The Great Gatsby

Lemuel Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels

The Mother in “Everyday Use”

Nora in A Doll House

Antigone and Creon in Antigone

ACTIVITY: Think about the story of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” then write an

autobiographical account of the event in the voice of one of the following characters: Homer

Simpson, Snow White (or any Disney princess), Sponge Bob, Squidward, Jack Sparrow, Forrest

Gump, Austin Powers, Dora the Explorer

15

“Catch Her in the Oatmeal”

If you actually want to hear about it, what I'd better do is I'd better warn you right now that you aren't

going to believe it. I mean it's a true story and all, but it still sounds sort of phony.

Anyway, my name is Goldie Lox. It's sort of a boring name, but my parents said that when I was born I

had this very blonde hair and all. Actually I was born bald. I mean how many babies get born with blonde

hair? None. I mean I've seen them and they're all wrinkled and red and slimy and everything. And bald.

And then all the phonies have to come around and tell you he's as cute as a bug's ear. A bug's ear, boy,

that really kills me. You ever seen a bug's ear? What's cute about a bug's ear? For Chrissake! Nothing,

that's what.

So, like I was saying, I always seem to be getting into these very stupid situations. Like this time I was

telling you about. Anyway, I was walking through the forest and all when I see this very interesting

house. A house. You wouldn't think anybody would be living way the hell out in the goddam forest, but

they were. No one was home or anything and the door was open, so I walked in. I figured what I'd do is

I'd probably horse around until the guys that lived there came home and maybe asked me to stay for

dinner or something. Some people think they have to ask you to stay for dinner even if they hate you.

Also I didn't exactly feel like going home and getting asked a lot of lousy questions. I mean that's all I

ever seem to do.

Anyway, while I was waiting I sort of sampled some of this stuff they had on the table that tasted like

oatmeal. Oatmeal. It would have made you puke, I mean it. Then something very spooky started

happening. I started getting dizzier than hell. I figured I'd feel better if I could just rest for a while.

Sometimes if you eat something like lousy oatmeal you can feel better if you just rest for a while, so I sat

down. That's when the goddam chair breaks in half. No kidding, you start feeling lousy and some stupid

chair is going to break on you every time. I'm not kidding. Anyway I finally found the crummy bedroom

and I lay down on this very tiny bed. I was really depressed.

I don't know how long I was asleep or anything but all of a sudden I hear this very strange voice say,

"Someone's been sleeping in my sack, for Chrissake, and there she is!" So I open my eyes and here at the

foot of the bed are these three crummy bears. Bears! I swear to God. By that time I was really feeling

depressed. There's nothing more depressing than waking up and finding three bears talking to you, I

mean.

So I didn't stay around and shoot the breeze with them or anything. If you want to know the truth, I sort of

ran out of there like a madman or something. I do that quite a little when I'm depressed like that.

On the way home, though, I got to figuring. What probably happened is these bears wandered in when

they smelled this oatmeal and all. Probably bears like oatmeal, I don't know and the voice I heard when I

woke up was probably something I dreamt.

So that's the story.

I wrote it all up once as a theme in school, but my crummy teacher said it was too whimsical. Whimsical.

That killed me. You got to meet her sometime, boy. She's a real queen.

16

Dan Greenberg, "Three Bears in Search of an Author," Esquire, Feb 1958, pp. 46-47.

A central concern in fiction is the concept of point of view which essentially involves the relationship of

the storyteller to the story or from whose perspective the story is told. In its simplest form, the point of view is that

of the author; however, many authors adopt a persona or mask--they select a voice through which they present the

work. The "I" of a quotation may be the writer, but it is more likely, in a complex short story, to be some other

personality. The difference between an author's attitudes and those of the narrator, a persona, is an important one.

In Swift's "A Modest Proposal" the attitude of the author is not the same as the narrator's. Swift has created a

narrator who advocates cannibalism of young children by the impoverished Irish as a remedy for overpopulation and

starvation. However, Swift was an Anglican minister who wrote the essay for humanitarian reasons. It is the job of

the good reader to determine what this extra distance between author and reader contributes to the story. Because

stories consist basically of incidents and characters, the point of view is the angle of vision, speaker’s perspective, or

narrative stance from which the reader observes these incidents and characters. The point of view affects how the

author reports information; narrates action; describes characters, setting, objects and emotions; or even interprets or

judges these elements. Additionally, it can affect or establish the tone of the work. The possibilities for point of

view can range from one end of the spectrum where the narrator is physically and emotionally detached and reports

only the facts of the story, to the other end of the spectrum where the narrator sees all, knows, all, and tells all. At

times, the narrator may be emotionally involved and may even attempt to influence the reader.

The narrator may be one of two specific kinds; a first person or a third person, and the type of narration

used may be identified by the personal pronouns used which are either first person pronouns (I, me, we, us, or they)

for first person narration, or third person pronouns (she, he, our, or their) for third person narration. The way the

story is told and the voice that tells the story are integral parts of the story. The narrator is an individual who is

participating in the process of fictional life just as the reader participates in real life. He is conscious of objects,

events, and people, just as is the reader. The colors and tones of the narrator's consciousness are in a sense projected

into the external world of the story, and thus the reader is able to experience both an objective world that is beyond

his physical limits and a subjective world informed by a consciousness quite different from his own. Joseph

Conrad's narration in Heart of Darkness echoes the word "darkness" throughout the story in order to suggest not

only a surface tone of darkness in describing his descent into Africa but also a substantial quality of darkness in all

existing things. Therefore, the objective world and the subjective world are harmonious in the darkness of Marlow's

consciousness.

Functions of Narrator

In a story or novel the narrator serves three general functions:

1.

He provides a consciousness that unifies the disparate elements of the story.

2.

He is a figure of authority whose degree of truth or falsity must be established so that the reader may

decide how much of the story he can believe.

3.

He organizes and operates in his fictional world with his own set of values - religious, philosophical,

ethical, epistemological, etc. These values have truth insofar as they are consistent, coherent, and

logical.

Kinds of Narrators

1.

The first-person central- - Here the narrator disappears behind the mask of a main character in the story.

The characteristics of this method are, first, that the observed action is limited to that which the narrator can relate

from his own perspective; and second, that the thoughts of the other characters are not revealed except as the

narrator knows them or can infer them. Edgar Allan Poe in his horror stories uses his main character as his first

person narrator so that the reader may participate more intimately with the narrator's fears, horrors, and near brushes

with death. In "The Pit and the Pendulum" the reader is on the table with the protagonist as the swinging blade

slowly descends. As the helpless man watches the alternating blade, the reader experiences his fears and tenseness,

feels the dampness of his nervous perspiration, and hears the swish and smells the pungent steel of the blade as it

makes its rhythmic swing back and forth. First person central perspective allows closeness with the main character

17

and provides the reader with insights that other characters in the narrative may not have; however it may lack the

reliability and

2.

First-person peripheral - This point of view is so closely related to the preceding one that only a few

distinguishing characteristics may be put forth. The chief difference is that the narrator who tells the story is often

an observer rather than a participant in the events of the narrative; however, the narrator may be a minor figure,

usually someone within the protagonist's group. Again the observed action and the interpretation are limited to what

the narrator can know or infer. In The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Nick Carroway can relate information

about the characters, Gatsby, Tom, and Daisy, only in terms of what he sees and hears. Nick says of Tom and

Daisy, "Why they came East I don't know. They had spent a year in France for no particular reason and then drifted

here and there unrestfully wherever people played polo and were rich together." One disadvantage of this

perspective is that the narrator may offer a narrative that is a bit too subjective, thus not as reliable as a third person

perspective.

3.

Third-person omniscient - Standing above and beyond the world of his or her story, the omniscient

narrator is an objective observer, not a participant or personally involved in what happens. This position allows for

more objectivity, hence more reliability. Here an omniscient narrator speaks in third person but does necessarily

restrict himself to the point of view of one character. As the term omniscient suggests, the author is all knowing.

Not only can he relate what the figures in the story say and do: he also can reveal what they think and how they feel.

It is as though the narrator can read the character's minds, interpret their actions, and even editorialize on their

significance to the story. In Jack London's "To Build a Fire," the narrator steps out of character and editorializes on

the character flaw of the "traveler" in the Yukon. "The trouble with him [the traveler] was that he was without

imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significances."

London, Jack

The omniscient point of view gives the narrator more freedom. He can report the thoughts and feelings of

the characters as if he has some kind of direct intuition. Additionally, his comments on the events of the narrative

are never oblique because he sees the action without the limitations or distortions of one angle of vision. An author

using third-person omniscient narrative stance becomes an almost godlike creature who, from his vantage point high

above the limited perspective of the characters, has complete control over the domain that he has created.

4.

Third-person limited - In this point of view the narrator is outside the action of the story and relates the

narrative as an observer rather than a participant. This method has the double advantage of appearing to give

objectivity to the story, and, at the same time, allowing the reader to identify more strongly with a single character.

The narrator's omniscience may be limited to one character.

However, since the narrator himself stands outside the actions, he sometimes implicitly judges the action

he is reporting. The narrator may pass judgment on the action or characters by the tone of his words and the style of

his sentences. In John Updike's story, "A Sense of Shelter," the narrator says, “Snow fell against the high school all

day, wet big-flaked snow that did not accumulate well." The word "against" seems to suggest an assault on the high

school that is persistent ("all day"). When the high school becomes a symbol of isolation, the assault of the snow

becomes an assault on isolation.

When the story is built around the experiences of one, rather than several people, it stands to gain unity.

However, because the story is limited to the observations of one character, the perspective may be limited.

5.

Third-person objective point of view is achieved through reporting factual detail, only that which can be

perceived by the senses. There is no access to the mind in any way. This perspective is sometimes confused with

the dramatic or stream of consciousness point of view, but it is different. Objective narrators never intrude to

evaluate, interpret or judge characters and their actions. In Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery," the narrator reports in a

very matter-of-fact manner the events of what at first seems a village celebration. The emotionless narrator reports

the events and provides background information. And even when the villagers prepare to stone the main character,

Tessie Hutchinson, to death, the narrator remains uninvolved and detached. The shocked reader is left to infer the

horror and betrayal Tessie feels. "It isn't fair, it isn't right." Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon

her."

6.

Stream of Consciousness point of view - This is one of the most popular of modern narrative stances. It is

also known as the central intelligence or dramatic point of view. This angle of vision is third person but is limited to

the mind of a single character through whose consciousness the action of the story reaches the reader. This is a

technique that seeks to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings, which pass through the mind. With this

technique as in a play, the author builds his story chiefly around dialogue. The voice is that of third person, but now

18

the author does not comment (or comments as little as possible), nor does he evaluate or editorialize.

Writing About Point of View

1.

What is the dominant point of view from which the story is told, and, more importantly, what was the

author’s purpose in choosing this method?

2.

Is the narrator of the story a participant in the story or just a witness?

3.

Does the story's point of view create irony?

4.

If the story has a first person narrator, is the narrator reliable? Are there any inconsistencies in the

narrator's presentation of the story?

5.

If the story has a third person narrator, is he or she omniscient? Does he or she have limited omniscience?

Is he or she objective? What was the author’s purpose for selecting this particular point of view?

6.

Does the point of view remain constant throughout the story, or does it shift? If it does shift, how and why

is this done, and what is the purpose for the shift?

Read “My Papa’s Waltz” and “Those Winter Sundays,” annotate, and discuss point of view based on the questions .

Those Winter Sundays

BY ROBERT HAYDEN

i·~·,~~:~'i<~··:··.·.·.··~······.-j(}····O·-·· - ....•..•................ , .. ,

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in' the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

oflove's austere and lonely offices?

My Papa’s Waltz

Theodore Roethke

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother's countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

19

AP lit & Comp-Unit t-Comparison and Contrast-"My Papa's Waltz" and "Those Winter Sundays"

Directions: The following questions are to guide you in annotating the poems. Briefly answer them on this

handout, and be prepared to thoroughly discuss them in large- and small-group discussion. (Read the poems

several times!)

1.

How would you characterize the relationship between father and son in this poem?

Consider the two figures of speech in the poem: the simile of "hung on like death" (I. 3) and the

metaphor of "waltzing" throughout the poem.

What do they add to the story line of the poem? Imagine, for instance, if the title were changed to "My Papa"

or "Dancing with My Father." How do you interpret the lines "My mother's countenance / Could not

unfrown itself" (II. 7-8)? Is she angry? jealous? worried? frightened? disapproving? Why doesn't she take

action or step in? Some interpret this poem to be about an abusive father-son relationship, while others read

it quite differently.

How do you interpret it? Use textual evidence from the poem to explain your reading.

Exploring the Text: "Those Winter Sundays"

What are the different time frames ofthe poem, and when does the poem shift from flashback to present day?

How does Hayden keep this shift from seeming abrupt?

What does the line "fearing the chronic angers of that house" (I. 9) suggest about the son's relationship with

his father and the kind of home he grew up in?

What is the meaning of "love's austere and lonely offices" (I. 14)? What effect does Hayden achieve by

choosing such an uncommon, somewhat archaic term as "offices"?

What is the tone of this poem? How do the specific details of the setting the speaker describes contribute to

that tone? Consider also how the literal descriptions act as metaphors. What, for instance, is "blueblack

cold"

20

21

Scoring Guide: AP English Literature, Question 2 (1997)

GENERAL DIRECTIONS: This scoring guide will be useful for most of the essays that you read; but for cases in

which it seems problematic or inapplicable, please consult your Table Leader. The score you assign should reflect

your judgement of the quality of the essay as a whole—its content, its style, its mechanics. Reward the writers for

what they do well. The score for an exceptionally well-written essay may be raised one point from the score

otherwise appropriate. In no case may a poorly written essay be scored higher than 3.

9-8: With apt and specific references to the excerpt, these well-organized and well-written essays persuasively analyze

how the changes in perspective and style reveal the narrator’s complex attitude towards the past. These essays identify

the complexity of that attitude and contrast the literary strategies that create complexity in the different sections of the

passage. Although not without flaws, these papers demonstrate an understanding of the text as well as consistent control

over the elements of effective composition. These writer’s read with insight and express their ideas with skill and clarity.

The 9 essays may be especially precise in the diction used in literary analysis.

7-6 These essays also analyze the narrator’s complex attitude but are less incisive, developed, or aptly supported than

papers in the highest range. They identify accurately some literary techniques by which Kogawa conveys the

complexities of that attitude, but they are less effective or less thorough in their analysis than are 9-8 papers. These

essays demonstrate the writer's ability to express ideas clearly, but they do so with less maturity and precision than the

best papers. Generally, 7 papers present a more developed analysis and a more consistent command of the elements of

effective college-level composition.

5 Although these essays describe the narrator's attitude toward the past, they may not convey significant understanding of

that attitude's complexity. Their analysis of how literary devices are deliberately employed to convey the narrator's

attitude is perfunctory or superficial. Often this analysis is vague, mechanical, or overly generalized. Although this

writing is adequate to convey the writer's thoughts and is without important errors in composition, these essays are

typically pedestrian, not as well conceived, organized, or developed as upper-half papers. Usually, they reveal simplistic

thinking and/or immature writing.

22

4-3 These lower-half papers address the task but reflect an incomplete or oversimplified understanding of the narrator's

attitude and/or fail to connect the use of literary devices to the construction and communication of that attitude. The

discussion may be inaccurate, unclear, misguided, or undeveloped. These papers may paraphrase rather than analyze.

They may not contrast literary strategies used in the different sections of the passage. The analysis of technique will

likely be meager and unconvincing; the essays typically lack persuasive reference to the text. Generally the writing

demonstrates limited control of diction organization, syntax, or grammar.

2-1 These essays compound the weaknesses of the papers in the 4-3 range. They may seriously misunderstand the

DDD

The excerpt from Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan is replete with striking images and sentiments of poverty,

weariness, and perseverance. Kogawa utilizes such techniques as shifts in point of view (and storytelling method) to

convey her theme to readers. She skillfully manipulates language, tone, and images, appropriately inserting relevant

Japanese words to emphasize the beauty and the values of the culture.

In the 1st paragraph, Kogawa’s perspective reflects the general experience of all the persecuted JapaneseCanadians during WWII. Her descriptions and limited omniscient point of view, (beginning with “We”) convey a

sense of overall suffering, endurance, and-nevertheless-cultural unity. Her images can be felt, as the everpresent

moisture of “rain, cloud, mist” (line 2) and tears. Here Kogawa successfully juxtaposes the 2 images of atmosphere

and emotion, describing the “air overladen with weeping” (line 2) and the [tear] – “salty sea” full of “drowning

speeches of memory - …small waterlogged eulogies” (4-5). It is through sentiments such as these that the author

gives life to her story and garners the sympathy of readers. The structure of these descriptions is conventional, full

of long sentences that accurately describe the experiences of a large group. Her language is grand, sensitive, utterly

incisive and melancholy. Kogawa selects detail that speak in images as well as emotions, comparing the wronged

subjects to “fragments of fragments” (line 11) and the “silences that speak from stone” (line 13). Yet, though

Kogawa explains they are “the despised rendered voiceless” (line 14), we realize that stories such as hers give these

martyrs (survivors and deceased) a voice. Her nostalgia conveys helplessness, sadness, and injustice, but the

overriding theme insists that the strong will prevail-to keep the culture and its memories alive. Kogawa also

employs various forms of figurative language – bounteous metaphors (“We are hammers and chisels” –line 9),

allusions (“We are the man in the Gospel of John” –line 17) to Christian Suffering/ subsequent resurrection, and

personification (“the sleeping mountain” –line 10) – to convoy an epic tale and vast expanse of suffering palpable by

all creatures and all of nature. This general, wide scope details the experience of the Japanese-Canadians without

separating them from the rest of the world. Kogawa utilizes this technique of universality and consistency well,

returning to her introductory images in the final line of paragraph 1. Here, she speaks of her people as

“undemanding as dew” (line 28), again emphasizing the image of tears and the theme of overall suffering endured

nobly.

In the 2nd paragraph of this excerpt, Kogawa shifts her perspective and style quite perceptibly. She now

uses a 1st person perspective in order to transform the experience (and its impact on readers) into a specific one.

Though we sympathized before, now we readers will be able to identify with individuals. Consistent with her

alternation in point-of-view, Kogawa’s diction also reflects the evolution from general to specific. As the narrator

retells these memories from the point of view of a child, her language is tense, simple, concrete. These “dream

images” (29) are disjointed at first, then solidify into definite memories of 1 specific event on the train. Sentences

gradually become more conventional (and complete) as the “dream” unwinds. The narrator of the future takes over,

describing things from the child’s vivid senses – eyes, ears, smell – whilst subtly implying a more mature

perspective. In this way, a more significant (but still easily understandable) meaning is given to the words. The

23

details are exact, colorful, honest – as a child would describe her situation. Throughout, the author includes

Japanese words such as “ojidan” and “Kavaiso” to reinforce the importance of her culture and its values over the

child and her acquiantances. These words are examples of beauty and sensitivity, also attempting to convey the

sense of family and intimacy felt by those on the train toward each other. They are all connected, suffering together,

trying to help each other glean some sort of peace from the sorrow and poverty. The girl’s umbrella is like “an

exotic bird” (53); such a simile describes the narrator’s childish hopefulness and attempts to make the situation

somewhat exciting – or, at least, better than it is. Kogawa ends the passage with an encounter between the narrator

(and her aunt) and a destitute woman with a baby. The former pair tries to empathize with the woman by sharing

their food. Though the child, naturally, is sensitive but still too shy and afraid to approach the woman, the aunt takes

the initiative. Her gesture is one of beauty and kindness, emphasizing the importance of sharing and selfishness

over charity that binds and obligates its objects. The woman’s reluctance to take charity is conveyed fully, her need

pride visible, as she looks down while accepting the orange. Yet, Kogawa insists, the appreciation and respect are

there, as the woman politely bows and takes the offering of kinship and comprehension.

GG

In the passage from Joy Kogawa’s Obasan the author uses changes in perspective and style to reflect the

narrator’s complex attitude toward the past. The author uses such literary elements as point of view, structure,

selection of detail and figurative language to accomplish this change.

In the opening of the passage the point of view is that of a mature adult. This adult has a sort of bitter

outlook let’s the readers know how the narrator feels about the events that she remembers. The “picture” in this

frame story is from the perspective of a young girl. The memories are those that a child would notice, but probably

not realizing what was really happening.

The structure of this poem is that of a frame story. The narrator explains her feelings toward the past, then

she tells the story of how she came to feel this way. This adds a mysterious and interested element to the reader’s

understanding of the narrator’s feelings.

The selection of detail in the passage shows the narrator’s experience with maturing. As a younger child

the narrator remembers the physical details of herself and those around her. She remembers things that were said

and what possessions she had with her. This shows the innocence of the child. As an adult detail is shown in

feelings. The narrator now sees in detail what is really happening and how the past events have changed her attitude

toward life itself.

Figurative language is used more when the narrator is speaking from an adult point of view. To the

narrator the sea is just a place to cast your hopes and wishes into. Her family and friends are faceless masses. As a

child the facts are the only thing the narrator recalls.

Point of view, structure, selection of detail and figurative language are important elements that help to

reflex the narrator’s attitude toward the past and how it changed through time.

R

The first three paragraphs of the passage serve as the author’s overview of the situation. They are written

from the point of view of the Japanese Canadians collectively, with no reference made to any individual or specific

incident. Broad generalizations are made about the situation, state, and qualities of these Japanese Canadians, all in

sentences virtually identical in syntax. The repetition of “We are…” presents the declarations as mere observations,

without attempt to persuade but with full conviction. The statements are all metaphors, commentary, or idealization

all are subjective in some degree, yet are presented as undisputable. The overall effect of this first section is to

provide the scenario for specific events and show what experiences and circumstances the participants have in

common.

The rest of the passage is in stark context to the opening. Presented in first person-but singular-style, it tells

of an individual narrator’s recollection of events. The first paragraph begins with, “The memories are dream

images,” followed by several sentence fragments depicting such partial images. The narrator then explains the time

frame in relation to herself, and goes immediately into detail about her clothing. Although unimportant, this is

24

realistic as a recollection of childhood and points out the personal significance of the passage rather than the

impersonal tone of the earlier section. The entire narration has such detail, especially in relation to other people: the

narrator, Stephan, the boy with the kitten, and Kuniko-san. All of the details are matter-of-fact; noting is compared

and there is no metaphor or allusion to greater significance. The scenario of the mother with nothing to give her

child is given to show the personal struggles of the Issei Nisei, and Sansei, even within the context of their collective

struggle.

F

Have you ever been to a place as a child and then later returned as an adult to find everything changed?

Yet on closer inspection, you percieve that the area itself has not changed, only your perspective of it has. Our age

often affects how we view events in life. In Joy Kogawa’s Obasan, the speaker is looking back over her life. Her

perspective and attitude towards life changes from when she was a child to when she was an adult.

As a child, she had a much simpler outlook on life. She realizes that something is happening (they are in a

train going away from home) but does not dwell on the reasons for moving. Rather, she is concerned with her

present surroundings as a young child is apt to be. Kogawa centers on a child’s point of view. She mentions only

the things that would catch a little girl’s interest; her new buttons, for example, or the kitten nearby. She centers on

small details, the black soot, the noise. We see the wonder in young girls eyes as she views her surroundings. She is

fascinated with her brother’s cast, for example. She describes the baby’s face as “squinched,” and red. She is afraid

of strangers yet willing to be of help wherever possible. She is young and impressionable.

In the other selection, the speaker is older, wiser. This is a direct contrast to the first selection. The whole

style of writing changes. The author centers on things that would captivate a more mature mind; the whole concept

of leaving everything behind, of moving in mass, of having no identity. Those are things that would characterize an

adult. The tone changes from one of wonder and anticipation, to one of heavy foreboding and despair. The speaker

now realizes that she is no longer one in a million, a unique individual, but is viewed as one of a million, simply a

number, of as little consequence as dew. They were sent inward to work, they have no choice. Her point of view

centers on the more colossal level. No longer is she concerned with the kitten or baby, her thoughts center on her

memory, drowning in the sea. The very diction the author uses conveys meaning to us. The word choice is more

educated. Words like “eulogies,” “momentum,” and “expulsion,” tell us that the speaker is no longer a child. She

also uses many comparisons and metaphors in this selection (hammers and chisels, arrows, silences, siloam,

pioneers). These could only be comprehended by an adult mind. The mind of a child is too simple to show these

complexities.

Joy Kogawa fully understood the human mind in its different stages in life and she incorporated this

knowledge in her book Obasan. She showed the differences in events taking place in a child’s life and in an adult’s

life through use of diction, selection of detail, point of view, time, themes, and overall mood.

Some prompts that required students to write about narrative stance:

1996

Hawthorne’s “Judge Pyncheon” from House of the Seven Gables: Analyze how the narrator reveals the

character of Judge Pyncheon. Emphasize such devices as tone, selection of detail, syntax, point of view.

1997

Joy Kogawa’s Obasan: Analyze how changes in perspective and style reflect the narrator’s complex attitude

toward the past. Consider elements such as point of view, structure, selection of detail, and figurative

language.

2004

Henry James’s “The Pupil” (1891): Analyze the author’s depiction of the three characters and the

relationships among them. Pay particular attention to tone and point of view.

2007

Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun: Analyze how Trumbo uses such techniques as point of view, selection

of detail, and syntax to characterize the relationship between the young man and his father.

2008

Aran from Anita Desai’s Fasting, Feasting (1999): Analyze how the author uses such literary devices as

speech and point of view to characterize Aran’s experience.

25

2010

Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801): The narrator provides a description of Clarence Harvey, one of the suitors

of the novel’s protagonist, Belinda Portman. Read the passage carefully. Then write an essay in which you

analyze Clarence Hervey’s complex character as Edgeworth develops it through such literary techniques as

tone, point of view, and language.

2011

George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1874): In the passage, Rosamond and Tertius Lydgate, a recently married

couple, confront financial difficulties. Read the passage carefully. Then write a well-developed essay in

which you analyze how Eliot portrays these two characters and their complex relationship as husband and

wife. You may wish to consider such literary devices as narrative perspective and selection of detail.

2.

ANALYZING CHARACTERIZATION IN LITERATURE

Literary characters are those creations that permit artists to play deity – to populate a fictional universe with

people and creatures of their own making. Characterization is the process by which an author fashions these

fictional characters. The great fictional characters of the world’s literature transcend the elusiveness of fiction

to achieve a sort of artistic permanence and reality unavailable to mere mortals. Who can forget the

captivating experience with Macbeth as he anticipates regicide and betraying King Duncan for his own

interests; King Lear’s sorrow and loss; Hamlet’s inner conflict and anger as well as Ophelia, the fragile girl,

who has collapsed under the burdens which confront her; the duplicitous ways of Madame Bovary; the

anguish of Heathcliff over the loss of Catherine; Hester Prynne standing of the platform with a “burning blush

and a haughty smile;” Willie Loeman’s self-deceptions and frustrations; or even Holden Caufield’s

depression, hatred of “phonies,” and his inability to articulate his frustration.

Major characters are the principal figures of the work; they are the protagonists in regard to conflict. If a

major character changes as a result of an experience, he is dynamic or kinetic. If he remains the same

throughout the course of the narrative, then he is a static character.

Some characters are classified as round. These individuals are complex, demonstrating many personality

aspects, have believable motivations, and are capable to surprising the reader or viewer. Hester Prynne in

The Scarlet Letter is a “round” character in that the reader is allowed to see many facets of her personality.

She is human – neither totally good nor bad. She is strongly motivated by passion and demonstrates an

admirable sense of loyalty towards her paramour by keeping his name a secret while at the same time

revealing vulnerability in terms of her qualifications as a mother. She grows as the novel progresses and is

ultimately able to move from a position, which is inferior to that of Hollingsworth to one that is superior. She

is capable of surprising the reader when, at the end of the novel, she returns voluntarily to the New England

setting and resumes the wearing of the dreaded letter.

Other characters are flat. These fictional beings are constructed around one central idea or characteristic and

never change or surprise the reader. Both Mr. Martin and Mrs. Barrows in Thurber’s “Catbird Seat” are flat

characters. Mr. Martin is a meek, clerk-like individual who treasures above all efficiency and routine. Mrs.

Barrows is portrayed as loud and aggressive, an individual who disrupts the routine at F & S. Throughout the

course of the story neither character experiences significant change or growth. In fact, Mr. Martin uses his

primary characteristics, those of efficiency and routine to ultimately eliminate the threat to his secure

existence, Mrs. Barrows. And ironically, it is Mrs. Barrow’s mouth and intrusive actions that prove to be her

downfall. At the end of the story, Mr. Martin is no different than he was at the beginning.

A stereotype is a conventional character representing a particular group, class, or occupation. Because his

character is conventional, he acts according to patterns. His appearance is familiar, speech predictable, and

actions standardized. Thus anyone who has seen an old movie or television show knows how to impersonate

a southern gentleman or a British Lord with the aid of only a few gestures, props, and speech intonations.

There are as many stereotypes as there are groups: the ragpicker, the doorman, the salesman, a politician, a

“typical” Texan, a senior citizen, the slow but good-hearted worker, the miser, the power hungry individual,

the stubborn person and so on

26

Additionally, literature may present allegorical or symbolic figures. Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie

Queene” is a classic example of a work where the characters represent people, places, actions, or concepts.

Thus the parade of the seven deadly sins, pride, gluttony, envy, avarice, lechery, idleness, and wrath are

presented as characters, but they truly represent the negative aspect of human behavior. Everyman and

Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress are additional examples of works with allegorical creations. The characters of

allegory can be as cartoonlike as Orwell’s menagerie in Animal Farm, as lively and intense as the children in

Golding's Lord of the Flies or as dramatic and memorable as the seamen of Melville’s Moby Dick or the

Freudian stops and symbolic characters in Heart of Darkness. The authors allegorical intentions may at

times help to explain the motivations and actions of his characters.

A character may be interpreted as symbolic when it appears that his actions and words seem designed to

represent some thought or view or quality. A character is not symbolic unless he symbolizes something.

Ultimately, a symbolical figure is one whose accumulated actions lead the reader to see him as something

more than his own person,

to see him perhaps as the embodiment of pure barbarism or redemptive power or hope. In Shakespeare’s Othello,

Iago is symbolic of pure evil.

Given a protagonist, the conflict of a story may depend on the existence of an antagonist – which may be human,

environmental, physical, mental, or emotional. A foil is a character who serves as a contrast to another, usually in

such a way as to work to the advantage of the leading character. The foil may help to illuminate the protagonist’s

positive qualities by demonstrating his own negative attributes, thus providing a clear and understandable contrast

for the reader.

A confidant, often used in drama, is a character to whom the protagonist reveals his inner thoughts; he becomes a

convenient device for the protagonist to speak his thoughts to without addressing them to the audience in the form of

a soliloquy. Thus, Hamlet, who at times does soliloquize, takes Horatio into his confidence, and it Horatio who at

the end of the play remonstrates the audience that “Here cracks a noble heart.” He continues, “Good night, sweet

prince, And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!

27

Finally, in almost all stories and plays there are background characters that populate the scene. Ordinarily,

these are of no special interest unless, as a mass, they assume an active role. In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar the mob

listens to and supports Brutus, but then, after Antony’s famous, emotional, and persuasive speech, changes and calls for

the head of the Brutus. In Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, the people as a group are the antagonists of Dr. Stockman.

He is the individual who has to stand up against the many.

Most fictional characters are developed in more than one way.

Ways in which an author might develop a character are:

1.

By what the character says and how he says it (dialogue)

2.

By what he does (actions)

3.

By physical description

4.

By psychological description

5.

By probing what a character thinks or feels

6.

By what others say about him

7.

By his environment

Clearly the reader should be alert to the actions of a character since this is the author’s way of showing, not

telling, what his personality is like. A character who either takes pleasure in the suffering of others or loses control and

causes pain, such as the narrator in Poe’s “The Black Cat” is seen as evil and evokes little sympathy. Yet, surface

appearances must be questioned. For example, in one scene of Melville’s Benito Cereno, Babo appears to be a faithful

servant shaving Don Benito in the presence of Captain Delano, the visiting captain aboard ship. In reality, Babo, with

razor in hand, is actually terrorizing Don Benito in order to keep him silent.

At times the appearance may be taken as a clue to a character’s real nature. The Prologue to Chaucer’s

Canterbury Tales consistently includes descriptions of physical details and dress, which serve as indicators of character

and social station. His description of the Squire includes the line, “Short was his gowne with sleves longe and wyde” –

usually understood to be details that indicate the squire was dressed in the latest fashion.

What a character says is one of the most revealing aspects of characterization. How does he say his words?

What are his habits of speech? His tone? Does the occasion color the tone?