Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece

advertisement

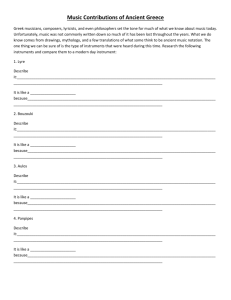

Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece A multi-day lesson created under the direction of the UC Berkeley History-Social Science Project. Alison Waterman Teacher Leader, UCBHSSP Orinda Union School District Find online: ucbhssp.berkeley.edu/hssp_lessons 2015 © UC Regents UNIT MAP 1 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece The Story of the Trojan War The Iliad tells of events near the end of the Trojan War, a war ancient Greeks believed was fought by Bronze Age Greeks and Trojans during the time when Mycenaean warrior-kings dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula. The legend of the Trojan War was widely known throughout the Greek world, and Homer clearly assumed that his audience was familiar with the larger story. Here is a brief summary of the plot line: It begins at the wedding of the sea-nymph Thetis to mortal King Peleus of Pithia (in Thessaly) when Eris, the goddess of Strife is left off the guest list. She shows up anyway and tosses a golden apple inscribed “To the Fairest” among the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Each goddess claims the apple, so Zeus selects the Trojan prince Paris to be the judge, for Zeus does not wish to anger any of these dangerous goddesses (one of whom is his wife, another his daughter). Paris awards the golden apple to Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, because she promises him the most beautiful woman in the world as a reward. Unfortunately for Paris, Helen is already married to Menelaus, the King of Sparta. Paris visits Sparta, and with Aphrodite’s help, convinces Helen to run away with him to Troy. Outraged, Menelaus, his brother Agamemnon, and a host of Greek warrior-kings declare war on the Trojans, determined to get Helen back. The Trojan War rages on for ten brutal years. The Iliad opens with a bitter quarrel between the Greeks’ military leader, Agamemnon, and their greatest warrior, Achilles, over a slave girl named Briseis whom Achilles won as a war prize. Agamemnon has had to give up his own slave girl, Chryseis, because she is the daughter of a priest of Apollo. At first, he refuses to return her, but Achilles speaks out harshly, accusing Agamemnon of greed. To punish Achilles, Agamemnon takes Briseis away from Achilles. As a result, Achilles has withdrawn from battle and refuses to fight except to save his ships and his own men, the Myrmidons. When his beloved companion Patroclus is killed in battle wearing Achilles’s armor, Achilles is moved to rejoin the fight in order to avenge the death of Patroclus by killing Hector, the Trojan who killed Patroclus. The Iliad ends with Hector’s burial, but the Trojan War continues until clever Odysseus, king of Ithaca, comes up with the idea of the Trojan Horse. The Greeks are then able to get inside the walls of Troy and sack (burn) the city. 2 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece Name ________________________________________ Date___________________ Class________ The Iliad: Learning From Literature 1. Directions: Read the following passage from your textbook. Highlight or underline the words that tell you whose perspective (or point of view) the Iliad reflects. The Iliad and the Trojan War: From Oral Tradition to Literature Among the earliest Greek writings are two great epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, composed by a poet named Homer around 750 BCE. According to ancient legend, Homer was blind and recited the Iliad and the Odyssey aloud. It wasn’t until much later that the poems were written down. The Greeks of Homer’s time believed that their ancestors had fought a ten-year war against the Trojans about 500 years earlier, (c. 1250 BCE). Like most epics, both poems describe the deeds of great heroes. The heroes in Homer’s poems fought in the Trojan War. In this war, Mycenaean Greeks fought the people of the city called Troy, in Asia Minor (now Turkey). The Iliad tells the story of the last years of the Trojan War. It focuses on the deeds of the Greeks, especially Achilles, the greatest of all Greek warriors. It describes in detail the battles between the Greeks and their Trojan enemies. (adapted from Ancient Civilizations, p. 272) The Iliad reflects the perspective of the ancient _______________________________________. The evidence for this is __________________________________________________________. As you know, artifacts provide a great deal of evidence about the culture that produced them (think of the Standard of Ur). Similarly, an epic poem like the Epic of Gilgamesh or the Iliad is a primary source that can provide evidence of many aspects of the culture from which it came. 2. Directions: Complete the chart below to show what you can learn about Sumerian beliefs from the evidence listed. Evidence (from the Epic of Gilgamesh) Enkidu is awestruck when he first sees the city of Uruk. Analysis (What does it mean?) Relevance (What can we learn about Sumerian beliefs?) After battling on the city’s walls, Gilgamesh and Enkidu become best friends. When Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh sets out on a quest for the secret of immortality. 3 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece Lesson Focus Question: What does the Iliad reveal about ancient Greek beliefs concerning war, love, and honor? 3. Directions: As you read the excerpts below from the Iliad and Dateline Troy, note evidence of Greek attitudes towards war, love, and honor. Evidence (Underline evidence of Greek attitudes towards war; circle evidence of attitudes Analysis (Explain what the evidence means, towards love; highlight evidence of attitudes towards honor.) or what it reveals about Greek beliefs.) Eyeing him [Agamemnon] angrily, swift-footed Achilles declared: “You clotheshorse for shamelessness, mind obsessed with profit, how could any Achaian [Greek] be prompt to obey your orders to march to war or face men in battle? I did not come here on account of Troy’s spearmen: why should I fight them? In no way have they ever wronged me. Never have they driven off my cattle or my horses; Never in rich-soiled Pithia did they lay waste the harvest, since great distance lies between us— shadowy mountains and echoing sea. But you, you shameless hulk, we accompanied here for your pleasure, to win honor for Menelaös and for you, you dog-face, from the Trojans. But none of these things you heed or care for—and now you even threaten to rob me of the prize to get which I suffered much, and the Achaians’ [Greeks’] sons gave it me. Never do I rate a prize to match yours when the Achaians lay waste some populous citadel of the Trojans, though mine are the hands that bear the brunt of furious battle… I’m not minded to stay here without honor, amassing you wealth and plenty.” (The Iliad, p. 29) Into Achilles’ hut burst Patroclus, his cherished friend and cousin. “The first row of ships is in flames!” he shouted. “If you won’t fight, at least lend me your armor. The sight of it might save the fleet.” Achilles agreed. (Dateline Troy, p. 58) When you’ve driven them from the ships, [Patroclus], come right back here! Turn back as soon as you’ve set the light of deliverance among the ships; leave the others to battle it out on the plain. How much I wish— Zeus, Father, Athena, and Apollo! — that not one out of all the Trojans might escape death, nor a single Argive [Greek], but that only we two should not perish, and together, alone, should loosen Troy’s sacred diadem [crown]! (The Iliad, p. 296) 4 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece “Alas, son of warlike Peleus, painful indeed is the news you must hear, of what never should have been— Patroclus lies dead, and they’re fighting over his body, his naked body: his armor bright-helmeted Hector holds.” So he spoke: a black cloud of grief closed over Achilles. With both hands he [Achilles] gathered up the dark grimy dust, scattered it over his head, befouled his handsome features, and on his fragrant tunic the black ash settled. There stretched in the dust, great in his greatness he lay; with his own hands he tore and defiled his hair… So terrible was his outcry, his lady mother heard him, ensconced in the sea’s depths, beside the Old Man, her father. (The Iliad, p. 339-340) Achilles buckled on the armor. He took up his spear and slid his sword in his sheath. Then he bolted outside, ready for revenge. With a thunderous shout, Achilles woke the Greeks and bid them make ready for battle…He could think of nothing but Hector…”Give my body to my father and mother,” Hector pleaded as he died. “Never!” screamed Achilles. He stripped Hector of his armor. Maddened with grief for Patroclus, he pierced Hector’s feet behind his heel tendons, threaded through the belt Ajax had given him, tied it to his chariot, and dragged Hector’s body through the dirt, around and around the walls of Troy. In horror, Priam and Hecuba turned their heads from the sight. (Dateline Troy, p. 60) 5 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece Lesson Focus Question: What does the Iliad reveal about ancient Greek beliefs concerning war, love, and honor? 4. Directions: Now sort your evidence into categories showing Greek attitudes towards war, love, and honor revealed in the Iliad. WAR LOVE HONOR 6 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece Lesson Focus Question: What does the Iliad reveal about ancient Greek beliefs concerning war, love, and honor? 5. Homework: Use your notes to write a thesis-evidence paragraph answering the lesson focus question. Be sure to include evidence from the charts you created while reading excerpts of the Iliad and Dateline Troy to support your claim. Thesis statement: The Iliad shows that ancient Greeks believed that war/love/honor (specify one) _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The evidence for this is found in ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ and ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ In the first example, _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. In the second example. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. From these examples, we can learn that ancient Greek culture __________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. Conclusion: This is significant because _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. 7 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece 8 Struggles for Justice: Love, War, and Honor in Ancient Greece Source: Paul Fleischman, Dateline: Troy, (MA: Candlewick Press, 1996), 58 & 60. 9