space

advertisement

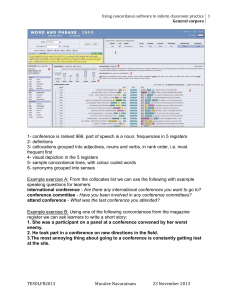

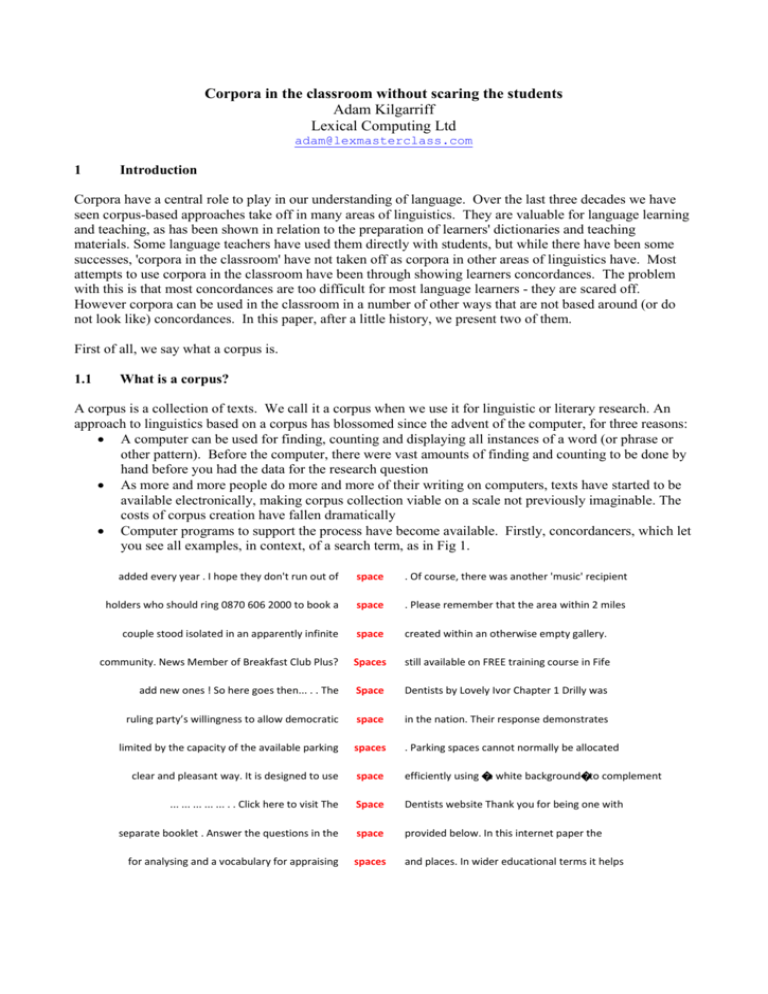

Corpora in the classroom without scaring the students Adam Kilgarriff Lexical Computing Ltd adam@lexmasterclass.com 1 Introduction Corpora have a central role to play in our understanding of language. Over the last three decades we have seen corpus-based approaches take off in many areas of linguistics. They are valuable for language learning and teaching, as has been shown in relation to the preparation of learners' dictionaries and teaching materials. Some language teachers have used them directly with students, but while there have been some successes, 'corpora in the classroom' have not taken off as corpora in other areas of linguistics have. Most attempts to use corpora in the classroom have been through showing learners concordances. The problem with this is that most concordances are too difficult for most language learners - they are scared off. However corpora can be used in the classroom in a number of other ways that are not based around (or do not look like) concordances. In this paper, after a little history, we present two of them. First of all, we say what a corpus is. 1.1 What is a corpus? A corpus is a collection of texts. We call it a corpus when we use it for linguistic or literary research. An approach to linguistics based on a corpus has blossomed since the advent of the computer, for three reasons: A computer can be used for finding, counting and displaying all instances of a word (or phrase or other pattern). Before the computer, there were vast amounts of finding and counting to be done by hand before you had the data for the research question As more and more people do more and more of their writing on computers, texts have started to be available electronically, making corpus collection viable on a scale not previously imaginable. The costs of corpus creation have fallen dramatically Computer programs to support the process have become available. Firstly, concordancers, which let you see all examples, in context, of a search term, as in Fig 1. added every year . I hope they don't run out of space . Of course, there was another 'music' recipient holders who should ring 0870 606 2000 to book a space . Please remember that the area within 2 miles couple stood isolated in an apparently infinite space created within an otherwise empty gallery. community. News Member of Breakfast Club Plus? Spaces still available on FREE training course in Fife add new ones ! So here goes then... . . The Space Dentists by Lovely Ivor Chapter 1 Drilly was ruling party’s willingness to allow democratic space in the nation. Their response demonstrates limited by the capacity of the available parking spaces . Parking spaces cannot normally be allocated clear and pleasant way. It is designed to use space efficiently using �a white background�to complement ... ... ... ... ... . . Click here to visit The Space Dentists website Thank you for being one with separate booklet . Answer the questions in the space provided below. In this internet paper the for analysing and a vocabulary for appraising spaces and places. In wider educational terms it helps disregarded and books were added where there was space on the shelves. The collection comprises c11,000 does not guarantee the availability of a parking space . A member of the University may register more and uninteresting, leaving a large amount of space with out any information. It isn't until you Tennessee accountant chris and now owns casino space more. Upcoming circuit buy-in enthusiasts from London . Ring 0870 241 0541 to book and pay for a space , for directions, and for details of onward fully as possible; if there is insufficient space in any of the boxes please continue on a separate Then he heard some manic laughter, and the space bus's communications monitor flickered on in like manner. This allows the viewer to probe a space that remains consistent for the duration of Baudrillard explains that holographic" real space " provokes a perceptual inversion, it contradicts Fig 1: A concordance. This is a sample of 20 lines for space in the UKWaC corpus, via the Sketch Engine. Advanced concordancers allow a range of further features like looking for the search term in a certain context, or a certain text type, and allow sorting and sampling of concordance lines and statistical summaries of contexts. Also, tools like part-of-speech taggers have been developed for a number of languages. If a corpus has been processed by these tools, we can make linguistic searches for, for example, kind as an adjective, or treat followed by noun phrase and then adverb (as in “she treated him well”) 2. History 2.1 General The history of corpus linguistics begins in Bible Studies. The bible has long been a text studied, in Christian countries, like no other. Bible concordances date back to the middle ages.1 They were developed to support the detailed study of how particular words were used in the Bible. After Bible Studies came literary criticism. For studying, for example, the work of Jane Austen, it is convenient to have all of her writings available and organised so that all occurrences of a word or phrase can be located quickly. The first Shakespeare concordance dates back 200 years. Concordancing and computers go together well, and the Association for Literary and Linguistic Computing has been a forum for work of this kind since 1973. Data-rich methods also have a long history in dictionary-making, or lexicography. Samuel Johnson used what we would now call a corpus to provide citation evidence for his dictionary in the eighteenth century, and the Oxford English Dictionary gathered over twenty million citations, each written on an index card with the target word underlined, between 1860 and 1927. Psychologists exploring language production, understanding, and acquisition were interested in word frequency, so a word’s frequency could be related to the speed with which it is understood or learned. Educationalists were interested too, as it could guide the curriculum for learning to read and similar. To these ends, Thorndike and Lorge prepared ‘The Teacher’s WordBook of 30,000 words’ in 1944 by counting words in a corpus, and this was a reference set used for many studies for many years. It made its way into English Language Teaching via West’s General Service List (1953) which was a key resource for choosing which words to use in the ELT curriculum until the British National Corpus (see below) replaced it in the 1990s. 1 See http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04195a.htm for a summary. Following on from Thorndike and Lorge, in the 1960s Kučera and Francis developed the landmark Brown Corpus, a carefully compiled selection of current American English of a million words drawn from a wide variety of sources. They undertook a number of analyses of it, touching on linguistics, psychology, statistics, and sociology. The corpus has been very widely used in all of these fields. The Brown Corpus is the first modern English-language corpus, and a useful reference as a starting-point for the sub-discipline of corpus linguistics, from an English-language perspective. While the Brown Corpus was being prepared in the USA, in London the Survey of English Usage was under way, collecting and transcribing conversations as well as gathering written material. It was used in the research for the Quirk et al Grammar of Contemporary English (1972), and was eventually published in the 1980s as the London-Lund Corpus, an early example of a spoken corpus. 2.1.2 Theoretical linguistics In 1950s America, empiricism was in vogue. In psychology and linguistics, the leading thinkers were advocating scientific progress based on collection and analysis of large datasets. It was within this intellectual environment that Kučera and Francis developed the Brown Corpus. But in linguistics, Chomsky was to change the fashion radically. In Syntactic Structures (1957) and Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965) he argued that the proper topic of linguistics was the human faculty that allowed any person to learn the language of the community they grew up in. They acquired language competence, which only indirectly controlled language performance. ‘Competence’ is a speaker’s internal knowledge of the language, ‘performance’ is what is actually said, and the two diverge for a number of reasons. To study competence, he argued, we do better to make native-speaker judgements of what sentences are grammatical and which are not, rather than looking in corpora where we find only performance. He won the argument - at least for a few decades. For thirty years, corpus methods in linguistics were out of fashion. Many of the energies of corpus advocates in linguistics have been devoted to countering Chomsky’s arguments. To this day, in many theoretical linguistics circles, particularly in the USA, corpora are viewed with scepticism. 2.1.3 Lexicography Whatever the theoretical arguments, applied activities like dictionary-making needed corpora, and in the 1970s it became evident that the computer had the potential to make the use of corpora in lexicography much more systematic and objective. This led to the Collins Birmingham University International Language Database or COBUILD, a joint project between the publishers and the university to develop a corpus and to write a dictionary based on it. The COBUILD dictionary, for learners of English, was published in 1987. The project was highly innovative: lexicographers could see the contexts in which a word was commonly found, and so could objectively determine a word’s behaviour, as never before. It became apparent that this was a very good way to write dictionary entries and the project marked the beginning of a new era in lexicography. At that point Collins were leading the way: they had the biggest corpora. The other publishers wanted corpora too. Three of them joined with a consortium of UK Universities to prepare the British National Corpus, a resource of a staggering (for the time, 1994) 100 million words, carefully sampled and widely available for research.2 2.1.4 Computational Linguistics and Language Technology The computational linguistics community includes both people wanting to study language with the help of computer models, and people wanting to process language to build useful tools, for grammar-checking, question-answering, automatic translation, and other practical purposes. The field began to emerge from 2 http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/ Chomsky’s spell in the late 1980s, and has since been at the forefront of corpus development and use. Typically, computational linguists not only want corpora for their research, but also have skills for creating them and annotating them (for example, with part-of-speech labels: noun, verb etc) in ways that are useful for all corpus users. In 1992 language technology researchers set up the Linguistic Data Consortium, for creating, collecting and distributing language resources including corpora.3 It has since been a lead player in the area, developing and distributing corpora such as the Gigaword (billion-word) corpora for Arabic, Chinese and English. Now, most language technology uses corpora, and corpus creation and development is also a common activity. 2.1.5 Web as Corpus In the last ten years it has become clear that the internet can be used as a corpus, and as a source of texts to build a corpus from. The search engines can be viewed as concordancers, finding examples of search terms in ‘the corpus’ (e.g., the web) and showing them, with a little context, to the user. A tool called BootCaT (Baroni and Bernardini 2004) makes it easy to build ‘instant domain corpora’ from the web. Some large corpora have been developed from the web (e.g., UKWaC, see Ferraresi et al 2008). Summaries and discussions of work in this area and the pros and cons of different strategies are presented in Kilgarriff and Grefenstette (2003) and Kilgarriff (2007). 2.2 History of Corpora in ELT As noted above, corpora have had a role in ELT for many years, in the selection of vocabulary to be taught. Since COBUILD, the role has moved to the foreground, from a theoretical as well as a practical point of view. John Sinclair, Professor at Birmingham University and leader of the COBUILD project, argued extensively that descriptions of the language which are not based on corpora are often wrong and that we shall only get a good picture of how a language works if we look at what we find in a corpus. His introductions to corpus use, Corpus, Concordance, Collocation (1997) and Reading Concordances (2003) give many thought-provoking examples. Sinclair’s approach has inspired many people in the languageteaching world. In parallel developments within the communicative approach to language teaching, authors including Michael Lewis (1993), Michael McCarthy (1990) and Paul Nation (1991) have made the case for the central role of vocabulary. This fits well with a corpus-based approach: whereas grammar can be taught ‘top down’, as a system of rules, vocabulary is better learnt ‘bottom up’ from lots of examples and repetition, as found in a corpus. Corpora (and word frequency lists derived from them) also provide a systematic way of deciding what vocabulary to teach. In the years since COBUILD, all ELT dictionaries have come to be corpus-based. As they have vast global markets and can make large sums of money for their publishers, competition has been fierce. There has been a drive for better corpora, better tools, and a fuller understanding of how to use them. Textbook authors have also taken on lessons from corpora, and many textbook series are now ‘corpus-based’ or ‘corpusinformed’. 2.2.1 Learner Corpora A corpus of language written or spoken by learners of English is an interesting object of study. It allows us to quantify the different kinds of mistakes that learners make and can teach us how a learner’s model of the target language develops as they progress. It will let us explore how the English of learners with different mother tongues varies, and the kinds of interventions that will help learners. Several corpora of this kind have been developed. 2.3 In the ELT classroom Corpus use in ELT can be classified as ‘indirect’ or ‘direct’. Indirect uses are, as described above, developing better dictionaries and teaching materials (and also testing materials, not discussed here). Direct methods are bolder: in these, we aim to use the corpus with the learners in the classroom. 3 http://ldc.upenn.edu The pioneer was Tim Johns, also working at Birmingham University, mainly with graduate and undergraduate students (see, e.g., Johns 1991). In the 1980s, on very early computers, he developed concordancing programs and strategies for using the concordances in the classroom: he coined the term ‘Data-Driven learning’.4 The arguments he presented for it were, and remain, that it shows the learner real language, that it encourages them to test hypotheses about how words and phrases are used, and language facts learnt in this way are very likely to be remembered. Concordances can operate as ‘condensed reading’ (Gabrielatos 2005). Various authors have made the case that the richest and most robust vocabulary learning come from extensive reading. But how should this be focused? How can we know whether enough vocabulary, or, the right vocabulary, will be covered, and will vocabulary items be encountered only very occasionally, so will not be reinforced? And what classroom exercises will support it? One response to these questions is to support extensive reading with exercises looking at concordances for the target vocabulary. In this way, the learners’ attention will be focused on the item, they will see many examples of it, and they can observe its meaning(s) and notice the patterns in which it occurs. Cobb (1999) presents a clear picture of how this can be implemented: he treats his students as lexicographers who need to establish the meaning and use of 200 previously-unknown (to them) words per week. This they do by looking at concordances. His experiments show marked improvement over other methods in learning and retention, and offer prospects of his first-year undergraduate students acquiring the 2500 words that, he estimates, they need to learn in their one-year course. Boulton (2009) takes a more focused approach, looking at linking adverbials, an area where learners clearly have difficulty. In his experiments, again with first-year undergraduates, he compared learning by one set of students using dictionaries with another using corpora, and found significantly better recall in the corpus group. His choice of focus is indicative of the area where ‘concordances in the classroom’ have most to offer: in relation to common expressions, often multi-word, which students will often want to use in their own speaking and writing, and where the challenge is not presented by the meaning so much as the patterns of use. For straightforward matters of meaning, the dictionary is a direct route to the goal, and good modern dictionaries will often also give a substantial amount of information about the word’s various meanings, collocations and patterns of use. But the information is often concise and abstract, to fit within the limitations of a dictionary entry, and often does not cover the particular situation in which the learner plans to use the word or phrase: it does not give a relevant example or collocation. The corpus is a place to go when the dictionary does not tell you enough. Taiwan has been a leading location for work in this area, with, among others, Yeh, Liou and Li (2007) using concordances to support the use of a variety of near-synonymous adjectives, rather than always using the most common; Sun and Wang (2003) exploring collocation-learning with high school students, and Chan and Liou (2005), with undergraduates; and Sun (2007) using a concordance-based writing tool with her students. Tim Johns also worked on a project in Taiwan shortly before his death, as described in Johns, Lee and Wang (2008). The ‘Teaching and Language Corpora’ (TALC) community held its first conference in 1994 and one has been held every two years since. Papers at the conference typically describe the lecturer’s use of corpora in their teaching. 3 Why are there not more corpora in classrooms? ‘Corpora in the classroom’ have been on the ELT agenda for twenty years but remain a specialist niche. People who attend TALC conferences are largely language teachers whose research interests are in corpus linguistics, so they are aiming to bring their research into their teaching. They are not language teachers who simply want more tools for their repertoire. Most English language teachers have not used them, and Some brief and stimulating examples of Johns’ style of work can be seen at http://www.eisu2.bham.ac.uk/johnstf/timeap3.htm#revision . Sadly, Tim Johns died in 2009. 4 may not have even heard of them. This is probably true at the university level and certainly true at the high school level. Why is this? Firstly, I think, because at first glance they do not meet language learners’ needs. To find out what a word means I can look it up in a dictionary or infer its meaning from the context in which I encountered it. Looking it up in a corpus presents lots of work, lots of distractions, and I might not find the answer I want in the end. Second, it does not address motivation. Central to the language teacher’s task is motivating the students. Presenting them with concordance lines – typically a page of fragments of dense text - is not promising. TALC practitioners’ answer to this is that, for advanced students, the motivation comes from the hunt to work out the rules and generalisations governing the vocabulary item. For some academically-inclined students, this is good. But most students do not want to learn how to do corpus linguistics, they want to learn English. The excitement and motivation about the method often relates to the teacher not the students. Third, it is not clear that it works. Most evaluations have been small-scale and situation-specific, and have not had resounding results. Finally, and, to my mind, underlying all the points above, concordances are hard to read. Whether they are fragments of sentences or full sentences, they come without a discourse context and they are likely to throw at the learner a whole array of complexities and difficulties. In my experience as a native speaker, reading concordances is a specialist skill that has taken a while to learn. In particular, it works well if you can very quickly understand the gist of the corpus line, so you know immediately the meaning, in this context, of the target word or phrase. Making this assessment depends on large numbers of clues embedded in collocations and syntactic patterns, usually within five words either side of the target. Often, culture-specific inferences need to be made to understand the sentence, making matters very difficult for learners of the language. In order to learn anything about word meaning from the corpus line, it is first necessary to decode the line itself: for learners, this is no trivial task. When reading concordances, it is better not to spend too much time on one line. The corpus should be looked at for what is apparent from repeated occurrences, and facts about the concordance line that are not immediately apparent will not contribute. Unless you work through a batch of concordances at some speed, the process will tend to be too drawn out for the patterns to reveal themselves. One part of the skill of reading concordances is knowing which lines to ignore, perhaps because the word is being used in an unusual or humorous way, or is not in a sentence at all. It is a judgement I (as an experienced corpus user and native English speaker) can make in a second or less. For many learners, simply getting the gist of each line will take a while and to expect them to work out which lines to ignore is unreasonable. 4 Between dictionary and corpus Learners’ dictionaries are designed to help learners understand and use words and phrases. A corpus is another resource to help with the same task. How do they relate to each other? They are both records of the language. The corpus is a sample of the language in the raw. The dictionary is a highly condensed version of roughly the same material. The relation between the two is easy to see when we consider how modern corpus-based dictionaries are prepared. One of the main inputs, at leading dictionary publishers including Collins, Macmillan and Oxford University Press, is word sketches: one-page corpus-based summaries of a word’s grammatical and collocational behaviour, as in Fig 2.5 Is this more corpus-like or dictionary-like? It is automatically-produced output from the corpus, making it corpus-like, but it is a condensed summary of what was found there, making it dictionary-like. On a continuum from corpus to dictionary, it is somewhere in the middle. 5 Word sketches are one of the functions in the Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al 2004), a leading corpus query tool in use at a number of dictionary publishers and universities worldwide. A free trial is available at http://sketchengine.co.uk . Most learners do not want to be corpus linguists, and concordances are unfamiliar and difficult objects. But dictionaries are familiar from an early age, sometimes even loved. Learners will not be put off if they are expected to look items up in a new kind of dictionary. This suggests a strategy for bringing corpora into the classroom: disguise them as dictionaries. Dictionary-users often find the examples are the most useful part of a dictionary entry. Moreover, where dictionaries are electronic rather than on paper, the traditional space limitation on examples disappears: there is room for lots of examples. This is an area where the corpus can help: they are nothing but examples. However they are not selected or edited examples. Choosing examples for a dictionary is an advanced lexicographical skill: they should be short, use familiar words, without irrelevant grammatical complexity, and they should give a typical example of the word in use and provide a context which helps the learner understand what it means. While we cannot yet program computers to do the task anything like as well as people, we can perform some parts of it automatically. We can rule out sentences which are too long, or too short, or which contain obscure words, or which have many words capitalised or lots of numbers or square brackets or other characters which are rare in the kind of simple, straightforward sentences we are looking for. We have done that in a program called GDEX (Good Dictionary Example finder, Kilgarriff et al 2008). The initial project was a collaboration with Macmillan, and the examples were used as a first-pass filter for them to add more examples to their dictionary. The machinery has been embedded into the Sketch Engine, and concordance lines can now be sorted according to GDEX score, so the ‘best’ ones are the ones that the user sees as their search hits. space ukWaC freq = 273022 object_of 86021 2.2 pp_between-i 2685 10.0 pp_above-i 205 5.9 watch 4113 9.21 paragraph 44 4.46 shop confine 1200 8.65 particle 22 3.64 occupy 1230 8.22 row 24 3.5 pp_per-i allocate 912 7.95 column limit 1163 7.76 word fill 1179 7.68 tooth enclose 566 7.41 building 410 143 3.1 dwelling 4.7 63 1.83 city 28 1.26 area 58 0.18 16 9.55 centre 19 0.14 44 5.48 17 3.09 unit 18 0.57 pp_down-i 76 4.2 83 2.22 person 26 0.57 left 3038 7.39 seat 20 2.2 save 1097 7.24 letter 39 2.1 reserve 523 7.08 star 20 2.07 devote 381 6.8 wall 32 1.97 breathe 344 6.79 cell 29 1.73 pp_for-i 15742 4.1 17 2.75 right 29 0.51 pp_around-i 515 4.6 building a_modifier 106533 2.7 109 6.31 open 29 1.73 building 25 3.2 sq.m create wheelchair pp_within-i 983 4.2 19 0.1 n_modifier 64957 2.6 10693 9.69 parking adj_subject_of 8065 2.3 6052 10.16 available 3224 6.63 fridge/freezer 40 6.13 green 3787 9.18 disk 2762 9.43 adjacent 91 6.37 freezer 49 5.93 outer 1732 8.75 storage 3084 9.32 cramped 20 5.79 fridge 52 5.62 public 5574 8.18 exhibition 1689 8.08 tight 70 5.76 cot 35 5.56 empty 1268 8.09 office 2984 7.75 limited 130 5.45 contemplation 27 5.43 ample 488 7.59 finite 17 4.83 970 8.05 breathing reflection 91 5.42 enough 1564 7.78 loft 426 7.57 scarce 16 4.8 recreation 47 5.4 limited 1110 7.54 gallery 872 41 4.64 luggage 35 5.16 extra 1325 7.46 roof 812 7.47 accessible 69 4.59 update 108 5.01 urban 959 7.45 floor 1535 7.41 inadequate 20 4.41 dryer 24 4.91 short 2051 7.37 living 798 7.39 suitable 91 4.41 storage 99 4.9 much 1740 7.21 studio 755 7.37 efficient 44 4.08 7.5 empty Fig 2. Word sketch for space drawn from UKWaC (truncated) While GDEX could be much better, it already makes it more likely that corpus examples will be readable. 5 Corpora in the classroom without concordances Concordance tools typically give the user lots of options as to how the search is specified and displayed, whereas dictionaries provide less: the lexicographers have decided what the learner should know about the word, so there is no need to complicate the learner’s experience by giving lots of options. So when disguising a corpus as a dictionary, the designer should make choices and not leave them to the user. We can use the word sketch machinery for finding grammatical and collocational patterns, and GDEX for selecting examples for those patterns. That then gives us a fully automatic collocations dictionary. The entry for space in this dictionary is shown in Fig 3. 6 space (n) object_of watch : We are also hoping to hold another Dinner in the Autumn – watch this space ! confine : Out of the bag the process will be quicker , but badges in confined spaces should last better for these reasons . occupy : A separate music library was formed in 1975 utilising space formerly occupied by committee rooms . allocate : Externally there is a single garage which is situated en bloc plus an allocated parking space . fill : Food food safe filler is used to fill any spaces in the container . enclose : Where a temple is found within an enclosed space , this is in most cases a rectangular space aligned with the temple . a_modifier open : 6 Open Spaces There will be a clean up day in November . Available at http://www.forbetterenglish.com modifies green : The Green Flag Award scheme is the national standard for parks and green spaces . outer : Moreover , we shall not be the first to place any weapons in outer space . ample : The bright reception room is a generous size , allowing ample space for a dining table . empty : Void size is a measure of how much of the medium consists of empty space . public : Streets are well overlooked helping to make public spaces feel safe . shuttle : Fly my space shuttle into the sun on my 105th birthday . exploration: Why am I so concerned about Britain 's role in space exploration ? n_modifier parking : 6 However , there would be a lot of scope for disputes where the number of physical parking spaces exceeded the number in the licence . disk : We do not set any limit on how much disk space is used . storage : There was no storage space for his personal possessions . exhibition : Recently lottery approval was received to completely restructure the existing building to provide considerably increased exhibition space built to the highest standards of design . office : The removal of interior partitions will also allow new office space to be created . living : Building and decorating companies are available now to help you to create the ideal living space for you . Corpora that motivate the students Wouldn’t it be nice if each student could work on English texts about a topic they were genuinely interested in? Rather than reading about safe textbook subjects like the family, or holiday traditions, or Harry Potter, they could find and learn from texts on gaming, hip hop, manga, or whatever they find fun. That would go a long way to addressing motivation. We have a tool that allows students to collect corpora on a topic of their choice: it is called WebBootCaT (Baroni et al 2006) and it uses the vast resource of the web. The user inputs five or six ‘seed terms’ in the domain of interest. Triples of seed terms are then sent to the Yahoo search engine, and Yahoo returns with a page of search hits; the program then gathers these pages and builds a corpus of them. A corpus of 300,000 words typically takes a few minutes, though, if the corpus is to be used extensively, further rounds of examining and improving the corpus are recommended (and supported by the software). Smith (2009) offered his Taiwanese first-year undergraduates a project in which they used WebBootCaT to build their own corpus. If the students are sufficiently engaged in the topic, they won’t be scared off. 7 Summary In this paper I have given some background on what corpora are and how they have been used in a variety of fields, focusing on ELT. Corpus use has become standard in dictionary and textbook preparation, but using them directly with students remains a specialist activity. This is explained as following mainly from the difficulty that learners have in reading concordances. I present an alternative strategy, in which corpora do come into the classroom – to help students where the dictionary does not tell them enough – but presented as dictionaries. Automatic techniques allow us to do this well: a word sketch is midway between corpus and dictionary We show how this can be done with an automatic collocations ‘dictionary’. We also present a response to the question of motivation: we provide technology for students to build their own corpora. I’ll leave the final words with one of Smith’s (2009) students who took the project: I find it special to have your own corpus. It is unique! You can make corpuses by your interests. That can make you know words easily because words are about your own interests. References Baroni, M. and S. Bernardini. 2004. BootCaT: Bootstrapping corpora and terms from the web. Proceedings of LREC, Lisbon: ELDA. 1313-1316. Baroni M., A. Kilgarriff, J. Pomikalek and P. Rychly) WebBootCaT: a web tool for instant corpora Proc. Euralex. Torino, Italy. Boulton, A. Testing the limits of data-driven learning: language proficiency and training. 2009. ReCALL 21 (1): 37-54. Chan, T. P., & Liou, H. C. (2005). Effects of web-based concordancing instruction on EFL students’ learning of verb–noun collocations. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(3), 231 – 250. Chomsky, N, 1957. Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton. Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, Mass. MIT Press. Cobb, T. 1999. Breadth and depth of vocabulary acquisition with hands-on concordancing. Computer Assisted Language Learning 12, p. 345 – 360. Ferraresi A., E. Zanchetta, S. Bernardini and M. Baroni 2008. Introducing and evaluating UKWaC, a very large Web-derived corpus of English. In Proc. 4th Web as Corpus Workshop. Morocco. Frances N. and H. Kučera, 1982. Frequency Analysis of English Usage, Houghton Mifflin, Boston Gabrielatos, C. 2005. Corpora and language teaching: Just a fling, or wedding bells? TESL-EJ, 8 (4). pp. 137. Johns, T. 1991. From printout to handout: Grammar and vocabulary teaching in the context of data-driven learning. In Johns & King (Eds.), Classroom concordancing. ELR Journal 4, 27–45. University of Birmingham. Johns, T., Lee H. C. and Wang L. 2008. Integrating corpus-based CALL programs in teaching English through children's literature. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 21:5, 483 — 506 Kilgarriff, A. 2007. Googleology is bad science. Computational Linguistics 33 (1): 147-151. Kilgarriff A. and G. Grefenstette 2003. Introduction to the Special Issue on Web as Corpus. Computational Linguistics 29 (3). Kilgarriff A, P Rychly, P. Smrz and D. Tugwell The Sketch Engine Proc. Euralex. Lorient, France, July: 105-116. Kilgarriff A., M. Husák, K. McAdam, M. Rundell and P. Rychlý 2008. GDEX: Automatically finding good dictionary examples in a corpus. Proc EURALEX, Barcelona, Spain. Kučera H. and N. Francis 1967 Computational Analysis of Present-Day American English. Brown University Press. Lewis, M. 1993. The Lexical Approach: the state of ELT and the way forward. Language Teaching Publications. McCarthy, M. 1990. Vocabulary. Oxford University Press Nation, P. 2001. Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press. Quirk R., S Greebaum, G. Leech and J. Svartvik 1972. A Grammar of Contemporary English. Longman. Sinclair, J. 1997. Corpus Concordance Collocation. Oxford University Press. Sinclair, J. 2003. Reading Concordances. Longman/Pearson, London/New York. Smith, S. 2009. Learner construction of corpora for General English. In draft. Sun Y. C. 2007. Learner Perceptions of a Concordancing Tool for Academic Writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning Vol. 20 (4), 323 – 343. Sun, Y. C., & Wang, L. Y. 2003. Concordancers in the EFL classroom: Cognitive approaches and collocation difficulty. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 16(1), 83 – 94. Thorndike, E. and I. Lorge 1944. The Teacher’s WordBook of 30,000 words. Teachers College, Columbia University West, M. 1953. A General Service List of English Words, Longman.