Being Bilingual Pushes Back Dementia by Five Years

advertisement

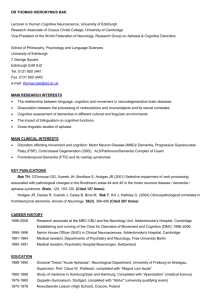

Being bilingual pushes back dementia by nearly 5 years: study A study by the University of Edinburgh in Scotland suggests those who speak more than one language, regardless of fluency, may have stronger protection against three different types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s. BY TRACY MILLER NEW YORK DAILY NEWS Wednesday, November 6, 2013, 4:11 PM SLOBODAN VASIC/GETTY IMAGES New evidence adds strength to the idea that speaking more than one language can help keep the brain younger for longer. Those who speak more than one language may enjoy built-in protection against the devastating effects of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, according to a new study. People who were bilingual or multilingual developed dementia an average of 4.5 years later than those who spoke only one language, researchers wrote in the journal Neurology. Dementia refers to symptoms such as memory and attention loss, communication difficulty, and decreased visual perception that result from damage to brain cells. Alzheimer's, the most common type of dementia, is the fifth leading cause of death for Americans over 65 and is thought to affect 5.2 million people. This study is the largest to examine the effects of bilingualism on dementia and the first to demonstrate the effects not just for Alzheimer's but other types of dementia, including vascular and frontotemporal, study author Dr. Thomas Bak of Scotland’s University of Edinburgh told the Daily News. Bilingual speakers "always practice a kind of brain gymnastics of having to select the correct language and suppress the other," which stimulates many different parts of the brain throughout their lives, Bak said. The study, titled "Bilingualism Delays Age at Onset of Dementia, Independent of Education and Immigration Status," took place among 648 dementia patients in the Indian city of Hyderabad, a cultural melting pot where much of the population speaks two or more languages regardless of class or education level. The average age of participants was 62.2 years. Slightly more than half the study participants spoke two or more languages. Researchers interviewed family members and caretakers to determine when the first symptoms of dementia began to appear. For bilingual speakers, the average age was 65.6 years, while it was 61.1 for monolingual speakers. LOIC BERNARD/GETTY IMAGES The study, which focused dementia patients in the Indian city Hyderabad, found that bi- or multilingual people developed dementia an average of 4.5 years later than monolingual people, even if they had received no formal schooling. Studies on bilingualism and dementia tend to look at immigrant populations — a selective group that makes it hard to separate factors like ethnicity, diet and lifestyle, Bak said. Most of the participants in this study had lived in Hyderabad "for generations," exposed to locally spoken languages including Hindi, Telugu and Dakkhini. "We can say that (the later onset of dementia) is not an effect of immigration," Bak said. "This is something to do with languages themselves." There was no additional benefit to speaking more than two languages, and speakers didn't have to be fluent in all their tongues — just being able to express oneself was enough, Bak said. "Very often you learn language in school. In India, you learn languages on the street," he said. "We found a group of illiterates, people who did not go to school at all, and in this group we found a difference (in when dementia symptoms started). So we can also say that the advantage of bilingualism is not due to different levels of schooling." Those who study a second language as adults can also be assured they're doing something healthy for their brain. Bak likened it to swimming, an exercise that uses all the muscles of the body. "In a way I would say bilingualism is the mental equivalent of swimming," he said. "You have to use different sounds; you have to be aware of different social norms. It stimulates a lot of different parts of the brain." tmiller@nydailynews.com