Att to 456 - O`Brien

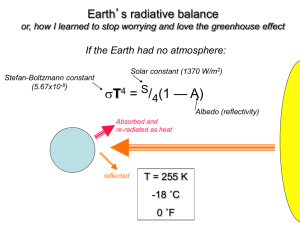

advertisement

30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien Australia’s post 2020 target for greenhouse gas emissions in UNFCC negotiations Submission by Terrence O’Brien To answer the technical questions posed in the PM&C Issues Paper requires some context. One needs to form views in the light of: the extent and rate of global warming; the extent to which it is driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (hereinafter abbreviated as CO2); the costs and benefits of the warming and their profile over time (which affect the net present cost or benefit of any warming); the costs and benefits of abating CO2 emissions (and their profile over time) relative to the costs and benefits of adaptation mechanisms; and finally, Australia’s particular circumstances and our national contribution to date in abating emissions compared to other countries’ performance and likely UNFCC commitments. The UNFCC process, like any large international political process, seems to have developed a substantial bureaucratic momentum. It appears unresponsive (indeed, vigorously resistant) to recent evidence that would suggest a more modest approach to greenhouse gas targetry, and a rebalancing of national efforts away from mitigation towards adaptation. The dangerous anthropogenic global warming meme has taken heavy damage over the last 5 years, and evidence questioning or qualifying it mounts daily. It seems likely to be in worse shape in 2020 than today. Australia should bring an up-to-date reading of climate change evidence and their policy implications and a realistic view of other countries’ greenhouse performances and objectives to its contribution to the Paris UNFCC 2015 conference. This submission notes where recent evidence seems to point, before using that evidence to derive suggested Australian policy positions on the three specific questions the identified in the PM&C Issues Paper. Developments in greenhouse measurement, science and modelling There seems no acknowledgement in the UNFCC documentation that the challenging experiences of recent decades, grudgingly acknowledged in the detail of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5 – and especially its Working Group 2 Report), should inform and impact on nations’ objectives to constrain greenhouse gas emissions beyond 2020. Nor does the PM&C Issues Paper mention these recent developments. (For an authoritative overview of main developments, see climatologist Professor Judith Curry’s 15 April 2015 Page 1 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien testimony to the US House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology, inquiring into the President Obama’s UN climate pledge.) To this reader of the IPCC’s work and broader climate science, economic and greenhouse policy debates, it appears that: Transitions to electrification and industrialisation based on economical carbon-based energy sources (principally coal) have been important elements in recent decades of economic growth in developing countries. This process has lifted literally billions out of poverty, and significantly improved health and life expectancies. More efficient energy sources are substituting for burning wood and dung, yielding environmental, living standard and health benefits in return for increased CO2 emissions. o “$10 billion invested in renewable energy technology in subSaharan Africa could give 20-27 million people access to basic electricity, whereas the same sum spent on gas-fired generation would supply 90 million.” (Matt Ridley, Electricity for Africa, 28 April 2015.) CSIRO research shows recent higher CO2 concentrations have led to a visible “greening” of the earth, particularly in arid zones (Science Daily, 8 July 2013). This has helped to support record agricultural output – a further appreciable benefit. Notwithstanding higher CO2 emissions and concentrations, there has been no warming at the earth’s surface for more than 15 years. There has been no warming at the tropospheric levels between the tropics (a more relevant indicator for human-caused warming) for some 20 years (Professor Ross McKitrick, Open Journal of Statistics, August 2014). Some one-quarter of the entire cumulative anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gasses having occurred over that period, suggesting climate response to CO2 emissions is not as great as earlier feared (and still modelled, in the IPCC’s AR5). The 75 global circulation models of the CMIP-5 suite used for IPCC scenario estimates of warming in the AR5 continue to run very hot, overstating actual warming trends since 1980 by a factor of 2 or more. This suite includes the CSIRO’s models. (Chart by Dr Roy Spencer, one of the creators and custodians of the satellite global temperature database maintained by the University of Huntsville at Alabama ). Page 2 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien The chance that such over-prediction of temperature trends may be an accidental consequence of ‘natural climate variability’ temporarily overwhelming model scenarios that are otherwise accurate is by now vanishingly small. Much more likely, the models are deficient and have estimated excessive climate sensitivity, and attributed excessive feedback effects, to greenhouse gas emissions and concentrations. See for example Judith Curry, The Wall Street Journal, 10 October 2014. There is a significant literature seeking to explain this over-prediction by the CMIP5 models, by now numbering over 50 hypotheses that could be grouped into a handful of different categories (e.g., ‘heat is hiding in the oceans’; ‘stadium waves’; low solar activity; particulates from volcanoes; aerosols, etc.). (See Dr David Whitehouse, Warming Interruptus: Causes for the Pause, GWPF Note 8, March 2014.) None of those explanations of the IPCC’s overestimation of temperature trends, alone or in combination, is reassuring for the hypothesis of dangerous anthropogenic global warming. If those factors’ recent but unpredicted impacts can explain the temperature ‘hiatus’ from the 1990s, perhaps their opposite but unstudied impacts caused the appreciable warming of the late 20th century. The AR 5 has also downgraded previous alarmist predictions of worsening storms and other high-cost consequences that might occur if there were significant global warming. The surface temperature databases on which general circulation models partly rest are being increasingly called into question, and might prove part of the cause of model over-prediction. The persistent gap between high global surface temperature records and lower satellite temperature records has caused mounting unease, as have the results of computerised ‘homogenization’ of the surface temperature records. The possibility that Page 3 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien a systematic upward bias has been introduced into the surface temperature records — in effect a computerised confirmation bias for the hypothesis of dangerous anthropogenic global warming — is now a matter of active statistical investigation in Australia and internationally. (See for example the International Temperature Data Review Project.) Lastly (and most uncertainly), the weak solar cycle (the weakest in over a century) has caused some who place particular weight on solar influences on climate to speculate that the next major move in global temperatures might be downwards, rather than a resumption of the late 20th century increases. (See for example Cold Sun, John L. Casey, 2011; or the Dutch government’s Climate Dialogue for a debate of these issues: What will happen during a new Maunder minimum?) Rather than possibly runaway, dangerous man-made temperature increases foreseen in some earlier IPCC Assessment Report scenarios, the most likely path for global temperatures now seems to be a modest degree or two of warming over the next century or so. The overall impact of all the foregoing uncertainties and errors has been to substantially affect the balance, and the distribution through time, of costs and benefits, of risks and payoffs, from front-loaded and vigorous attempts to limit anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gasses with technologies available today. The amount of warming in prospect is likely to yield net benefits, rather than costs, over the next hundred years or so. (See, for example, Matt Ridley’s 6 April 2014 summary of the implications of IPCC AR 5 Working Group 2: Global warming looks like it will be cheaper to cope with that to prevent, and his argument that this view is a clear consensus of those economists using the IPCC scenarios of warming.) The progress of technology over the next century is likely, on the last century’s experience, to yield significant low-cost options for a back-loaded reduction in carbon emissions. What those technologies will be is as unforeseeable today as mass air transport, computers, smart phones, factory robots, nuclear energy, fracking, the internet and genetic engineering were 100 years ago. But modest guesses relevant to cheaply abating future greenhouse gas emissions include fourth-generation nuclear power (in which China is heavily investing), and more efficient battery storage from intermittent energy sources. A continued hiatus in temperature rises, or even a decline in temperatures, remain possibilities that sensible global and national policies ought incorporate into their planning. Sound policies should be robust to the full range of greenhouse outcomes, not just the alarmist pole of the continuum of possibilities. Other nations’ objectives and performance Realistic assessment of other countries’ objectives for global climate agreements and the commitment revealed by their performance are helpful for considering Australia’s input to the UNFCC negotiations. Page 4 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien Very few politicians, nationally and internationally, have publicly noted the recent trends in climate change evidence noted above, or openly argued through their implications for national mitigation policies. This perhaps owes in part to the vicious ‘gatekeeping’ role on acceptable views in academia and the media; see for example the behaviour revealed in the ‘Climategate’ e-mails, the attempt by the BBC to silence former Chancellor Nigel Lawson, and the hysterical and grossly misinformed reaction to the establishment of the Australian branch of the Copenhagen Consensus Group at the University of WA.) What politician needs the grief of a battle against highly organised green lobbyists? But politicians’ actions speak louder than their words, and much louder than their silence. It is useful to review briefly the realities of other countries’ actions and their consequences. Many EU members have taken the global lead in restricting emissions of greenhouse gasses in the belief that domestic adjustment would be low cost, and that renewables would quickly become substitutes in cost and reliability for traditional base load generation. They have been proven wildly wrong. (See, for example, Dr Benny Peiser’s Testimony on EU climate policy to the Committee on Environment and Public Works of the US Senate, 3 December 2014.) Many EU economies are suffering heavy damage from energy price rises greatly outstripping inflation, consequent ‘energy poverty’ among citizens, losses among base-load electricity generators, losses among energy intensive industries and ‘carbon leakage’ to developing countries and the US (where fracking has reduced US greenhouse emissions by more than all the solar panels and windmills in the world, while significantly lowering gas and electricity prices). Faced with these consequences of failed policies, European countries will obviously be keen at the UNFCC to induce others to follow them down their failed path. Notwithstanding professions of commitment to greenhouse gas reductions, Germany is building modern coal-fired power stations as fast as possible, as the combined limitations of its intermittent supplies from renewables and its self-imposed de-commissioning of nuclear plants force greenhouse-damaging adjustments to keep the lights on and limit increases in energy poverty (if not to keep industry competitive). See for examples Professor Fritz Vahrenholt, 5 December 2014, Germany’s manmade energy crisis deepens. For all President Obama’s enthusiasm on greenhouse issues, the US Energy Information Administration predicts on current policies moderate growth in US CO2 emissions from 2013 levels to 2040, as CO2 savings from switches from coal to fracked gas and new renewables in electricity generation are offset by growth in industrial CO2 emissions as a result of relatively cheap electricity, gas and feedstock prices (Annual Energy Outlook 2015). Canada quit the Kyoto protocol in December 2011, after substantially overshooting its earlier commitments. Its energy endowments and policy history seem likely to discourage any dramatic post-2020 UNFCC commitments. Page 5 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien Japan’s CO2 emissions are rising again as it relies more on coal-fired power in place of nuclear energy (see Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 13 April 2015). Forty-three new coal-fired plants are under construction or planned. In November 2013 Japan relaxed by 25% its earlier commitments to greenhouse emission reductions by 2020. Russia rejected commitments to greenhouse gas reductions beyond its initial Kyoto commitments ending in 2012, and might be expected to be cautious about committing to significant reductions beyond 2020. China is building a coal-fired electricity plant every 7 to 10 days. By 2040, China’s coal-fired power capacity is expected to be 50 per cent larger than today’s (Institute for Energy Research, 24 April 2015). Its expectation that its CO2 emissions might peak around 2030 is not a binding commitment, and is a projection of how it sees its coal fired and other generation capacity evolving. India is to overtake China as the world’s biggest coal importer. Its Government will not hold its citizens in unnecessary poverty to underpin bold international commitments to CO2 emission reductions. The Government is cracking down on foreign-funded NGOs such as Greenpeace that are argued to be acting against India’s national interests in modernisation and poverty reduction (Hindustan Times, 28 April 2015). PM Modi has observed: “The world guides us on climate change and we follow them? The world sets the parameters and we follow them? It is not like that.” Pakistan is accepting Chinese finance of some US$15.5 billion to build new coal-fired power plants to reduce chronic electricity shortages (Wall Street Journal, 19 April 2014). Indeed the rise of the Chinese-financed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank owes significantly to the World Bank Group’s effective ban on financing coal projects and coal-fired power projects. Protracted inaction in modernising World Bank governance has finally produced a development bank so biased to rich country sensitivities that it will not lend on a key family of projects most wanted by poor countries to alleviate poverty. The developing world in general seems unlikely to make significant, enforceable commitments to greenhouse gas reductions or caps in the UNFCC process. Themes relevant to Australia’s negotiating position The combination other countries’ emissions performance and intentions, recent developments in the climate debate and remaining uncertainties point to several ideas that should inform Australia’s policy towards UNFCC processes in Paris: The temperature ‘hiatus’ cannot be ignored and will cast a pall over UNFCC attempts to secure significant binding agreements to reduce greenhouse emissions beyond 2020. The dangerous anthropogenic global warming hypothesis has been severely damaged by the last decade’s evidence and debate. By 2020, the Page 6 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien case for front-loaded, expensive mitigation actions seems likely to be weaker still. Significant developed countries have breached their Kyoto emission commitments, unilaterally reduced them, or quit them. There is no reason to expect any better performance by them after 2020. Serious economic, poverty and energy problems evident in the EU as a result of unwise earlier pushes to implement excessively ambitious green energy schemes stand as a warning to other countries tempted to follow EU paths. As the Issues Paper shows, Australia has been a stronger than average performer in meeting targets to reduce emissions by 5 per cent from 2000 levels by 2020 – very significant achievements given our economic structures, resource endowments and population growth. While the parties in the UNFCC have agreed post 2020 national targets are for national determination, not international negotiation, there will obviously be temptation for many governments to play to domestic green lobbies by claiming ‘our commitments are bigger than other countries’”. The obvious (if dishonest) tactics for other countries wishing to apparently offer dramatic reductions in CO2 emissions are to choose an early base year (e.g. 1990), and a distant end year (e.g. 2030). o The early base year allows countries to claim as policy achievements the general advances in energy efficiency and the decline in the energy intensity of GDP, plus in some cases historical accidents such as the termination of uneconomic energy intensive industries in central Europe and the former East Germany. o The distant end year means success or failure is too hard to predict, too far in the future to be a concern of current governments, and to hold open the possibility that future developments (in energy efficient technologies, or a continued halt in temperature trends or their reversal) might let successor governments off the hook cheaply. What should Australia’s post-2020 target be, and how should it be expressed? Australia has a record of making international commitments seriously and actually meeting them. It should avoid bold commitments in Paris, even if others are claiming to offer them. The target should be expressed off a 2020 base year to underscore its path towards achievement of its earlier Kyoto commitment, and ensure a realistic base for subsequent reductions. It also preserves some flexibility should evidence against front-loading expensive mitigation measures continue to build. The end year for Australia’s offer should be 2025, reflecting the present uncertainties arising from both ‘the pause’ and the unresolved attempts to explain why the CMIP-5 models are running hot. This would also underscore commitment to a more transparent and accountable political horizon for the target. This too would preserves some flexibility should Page 7 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien evidence against front-loading expensive mitigation measures continue to build by 2020 and beyond. As to the quantum of the commitment, Australia should use the evidence noted above about its particular economic and population growth characteristics and uncertainties about the causes and future of the ‘hiatus’ to argue for a low national commitment that it can argue from its past performance that it will assuredly meet. A modest and short post 2020 target would realistically reflect the fact that presently foreseeable small global warming over the next century will confer net benefits, and does not warrant expensive (but probably futile) front-loaded mitigation attempts. If future evidence warrants larger, back-loaded reductions, they are likely to be made at less cost with more advanced technologies than now available. The ‘caution while learning more’ rationale for this approach needs to be openly argued by the Australian Government as a realistic response to uncertainties and the modelling failures revealed in recent experience. Australia’s proposals should not offer integration with global carbon markets, which experience has shown to be shallow, volatile, prone to rorting and corruption, and with often-doubtful connection to real environmental benefits. What would the impact of that target be on Australia? A modest target of short duration as suggested above should desirably have few adverse effects on the Australian economy, while nonetheless keeping Australian research and investment connected to any global advances in tomorrow’s cheaper green technologies. The fewer empirically unjustified mitigation imposts Australia embraces in the UNFCC processes, the more degrees of economic and fiscal freedom it retains to pursue its preferred national priorities in practical environmental and climate policies. There will certainly be climate change in the future, as there always has been in the past. Whatever the pace and direction of tomorrow’s climate change, Australia will continue to experience droughts, floods, fires, coastal erosion and soil degradation. There are national adaptation policies in these areas of certain benefit that Australia could rationally adopt, regardless of what the rest of world agrees, or fails to agree. These adaptation policies should make up an increasing part of Australia’s greenhouse efforts. They will pay dividends to Australians’ welfare, regardless of how present climate uncertainties are resolved. Which further policies complementary to direct action should be considered? As argued above, unless future evidence supports credible and more ambitious international agreement to reduce CO2 emissions, the direct action program should be progressively re-aligned away from mitigation Page 8 of 9 30 April 2015 Terrence O’Brien efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and toward adaptation efforts. Page 9 of 9