Who Should Shoulder the Cost on Solid Waste

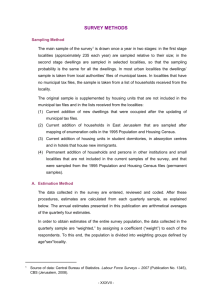

advertisement