Vet Ethnography

advertisement

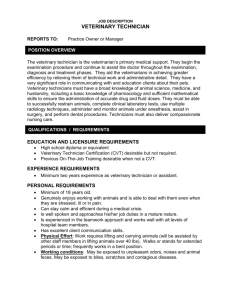

Yates 1 James Yates Stacy Kastner EN 1173-01 21 April 2014 Mini-Ethnography of a Veterinary Clinic Throughout the course of time, veterinarians have been and still are crucial in the survival of the human race by being crucial to the survival of our animals. However, there is not that many veterinarians in the world compared to doctors, lawyers, musicians, or teachers. Many people would say that this veterinary shortage is from the amount of knowledge that skilled veterinarians have to possess. Imagine the knowledge of a human doctor and all of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology that they have to know and practice. Take that information and multiply it by the several thousands of animals that there are and add in the entire knowledge of a pharmacist, and you have a veterinarian. Literacy Review That literacy and amount of knowledge and skill that these people have to have is simply astounding. Research from veterinarians themselves show that there are several different types of literacies that today’s veterinarians have to be able to practice. Dr. David Pinson speaks to veterinary writing ability in the form of writing lab requests and diagnostics in his article “Writing diagnostic laboratory requisition form histories” (Pinson). In addition to Dr. Pinson, Frank O’Sullivan in his article “Prescription writing and record keeping requirements for a veterinary Yates 2 practitioner” deals with the parts of writing as a veterinarian in writing prescriptions and record keeping (O’Sullivan). In a veterinary clinic, communication is also a good literacy and ability to possess. Dr. Michael Paul discusses the art of veterinary communication with cliental in “You say tomato”, while Dr. David Lane discusses the practical application and need of effective communication within the clinic itself between veterinarians and technicians in his article “Writing on the wall” (Paul, Lane). These research points to two key literacies of veterinarians, which are writing histories, prescriptions, and lab reports, and communicating with clients. I agree with this assumption on account of my recent observations, interviews, and several years of past experience working with and under certain veterinarians. However, from these experiences and observations, these authors have left out two very important other literacies - those of the technology used and being able to read clients and their animals. Therefore, I believe that in addition to writing in charts, prescriptions, and diagnostic reports, and having to effectively communicate with clients, I believe they also use advanced technologies and equipment, and read animals and their owners. Methods All Animal Hospital houses some of the most talented and knowledgeable veterinarians and veterinary technicians I have ever met. The owner and founder of the establishment, Dr. Lynn Cox, graduated from Mississippi State University in 1983 with a Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine. After owning a practice in Tupelo, Mississippi for several years, he moved back to Southaven where he now owns All Animal Hospital (Cox Interview). Each day, numerous cases of unique animals with Yates 3 unique symptoms walk, crawl, or fly through his doors, and he is literate and knowledgeable enough to know how to treat each and every one of them. This is why I chose All Animal Hospital for my observation and Dr. Cox for an interview. There are basically six main parts of the hospital, which are the front waiting room, the exam rooms, the hall behind the exam rooms, the surgery prep stations, the surgery and X-ray areas, and the kennels. In the front waiting room, the receptionists are hard at work taking phone calls, making appointments, and checking in clients for their appointments. The three exam rooms house the technicians and are the site of all of the basic appointments and checkups and are also where I spent most of my observation. Behind the exam rooms is a hallway with copious amounts of machines and equipment including computers, prescription printers, electrolytes labs, stool sample and microscope lab, and waste containers. This hallway backs up to a larger room with two wet tables mainly used for surgery preparation. This room contains equipment such as a centrifuge, blood sample tests, textbooks, lamps, and solute drips. At the back of this room there are two more room, the surgery room and X-ray room. In the X-ray room, there are displays, computers, and, of course, an X-ray machine. In surgery, there is equipment such as a heart monitor, surgical supplies, tracheal tubes, a radio, surgical kits, gas machines, and a laser. I arrived at All Animal Hospital at 7:30 a.m. to find the veterinary technicians hard at work making sure the clinic was ready to open at 8 o’clock sharp for the line of clients and their animals already lined up outside of the doors. I took this opportunity to take pictures of all of the equipment that was typically used during Yates 4 the day shifts and to copy down some chart information. Throughout the course of the five hours on a Saturday morning, I observed over twenty different appointments on twenty different animals. These animals had varying conditions and reasons for visiting the clinic ranging from annual appointments, to wing clips, to surgery checkups, to the declawing and detailing of five day old boxer puppies. All of these I was able to observe, note, and assist with given my prior experience working for Dr. Cox and his team. Directly after the observation, I was given the privilege of interviewing Dr. Cox himself. Based on my interest in becoming a veterinarian myself someday, my questions followed the lines of “How are your college writing courses utilized in your career today,” “What kinds of skills do new veterinarians fresh out of college need to possess,” and “What kinds of technology do you use as a vet daily?” Even though he has been practicing medicine for over 30 years, he says it’s still a practice of the knowledge that you learn before, during, and after vet school. After conversing and discussing the literacies of his veterinary practice and experience, I have found that there are four basic literacies to being a veterinary, which include reading, writing, technology, and communication. Results Writing Writing in a veterinary clinic is very different than writing in a typical workplace with memos, reports, contracts, etc. The bulk of writing done is through a system of charts. Each time clients comes in with their animal, a chart must be either found with their name and animal in it from a previous visit or a new one must be made. It is through the literacy of the secretaries that this is done, and they then Yates 5 place the chart into a rack for the veterinarians and technicians to know that there is someone waiting to be seen. Each chart is then filled out with basic information such as the name of owner, address, phone number, and information about their animal or animals. This information includes names, breed, color, sex, weight, temperature, date of birth (or approximation), and what they are in the clinic for whether it be for an annual checkup, something is not quite right, or if there is an emergency. All of this must be written down into the charts by the technicians and veterinarians alike in order for the clinic to run as efficiently as possible. Other types of writing include prescription writing, medical supply order forms, and diagnostic lab reports. When writing diagnostic reports, veterinarians have to be conscious of several different things, such as hand writing, information to put on the request sheet, and what information to report on the sample. When putting information on the request sheet about the animal, there are six questions to ask about the patient’s history. What is the primary reason for evaluation? What is the duration and frequency of the problem? What are the objective clinical findings? What are the differential diagnoses? What specifically was sampled? What is the appearance of the tissue or lesion? These questions should reflect the information placed on a diagnostic report (Pinson 408-9). Prescriptions are written for the client and should be legible and easily understood. In addition, certain information is required to be on all forms of prescription drugs. These include “name of remedy, quantity, date issued, manner and site of administration, dose rate, withdrawal period, animal description, name of client, period of validity, instructions, precautions, risks, and name of the veterinarian” (O’Sullivan 2). All Animal Hospital Yates 6 uses computer programs and printers to make all of their prescriptions legible and easy to read by simply typing everything and printer out labels with all of the needed information as well. This writing is key for veterinarians to effectively communicate to their clients what needs to be done for the animal. Reading Whether they are on a tight schedule or could stay in the clinic all day, veterinarians must be able to read and accommodate whatever needs to client may have in regards to their animal. Types of reading can range from simply reading a magazine to reading a sample to reading animals and humans. Veterinarians should pride themselves on their ability to read animals. Most doctors read people; however, those people can tell you what is bothering them and what they want. Animals on the other hand cannot speak more than to tell you what hurts and what does not when you touch a particular spot. Also, reading tissue samples like fecal matter and information taken such as temperature can also have an effect on what the outcome and diagnosis of the animal will be. Reading their owners and your clients is also not an easy task. Veterinarians need to be able to know what type of treatment for which the owner is looking and what sort of compassion to use. This enables the veterinarians to successfully treat their patient. Continuing education plays a large role in the lives of veterinary practitioners. According to Cox, when he graduated vet school the amount of veterinary knowledge was doubling every ten years. Ten years ago, it was doubling every 14 to 16 months. Now, once you graduate college, you are basically obsolete already. That is why continuing education is so important. Veterinarians are Yates 7 required to take at least 30 hours worth of seminars and lectures a year to keep up with the increasing amount of new knowledge and medical practices and drugs coming to light. Cox takes roughly 60 hours a year because he believes that in order to be a better veterinarian, he must always be knowledgeable about the newest techniques and drugs available to him and his clinic (Cox Interview). All around his clinic, All Animal Hospital, lay veterinary magazines, drug handbooks, and the latest surgery techniques textbooks in order for him and all the people who work with him to read and memorize. The reading and continuing education plays a key role in making sure that the veterinarians stay up to date with the latest veterinary news, accomplishments, developments, and new techniques in medicine. Technology The technology that encompasses a veterinary clinic is astounding. There are machines in every corner of the building. Machines from EKG’s, to ultrasounds, to washing machines, to centrifuges line the walls. Each machine is owned and operated by the technicians and veterinarians of that clinic. Because of this, each worker is required to know what each machine is and how to work it. Other technologies such as several computers and microscopes sit on countertops attached to printers and online charts of clients. Each computer is password protected, and, again, each worker knows how to work and use the computers efficiently. Some pieces of equipment are not mounted to walls or roll around the building. Some are in the pockets of the veterinarian and the technicians. Equipment like stethoscopes, otoscopes, and tracheal tubes can be found throughout the clinic and throughout the workers. Each of these tools are used and operated by the Yates 8 workers on a daily basis. This technological literacy of the technicians and veterinarians is therefore very diverse and covers a wide range and variety of machines and tools. Communication “Communication is key and 95% of all problems” is what Dr. Cox told me when asked about how he communicates with clients. He states, “Communication is 95% of all problems in a veterinary clinic. No matter how much you can read an animal, if you cannot effectively communicate to the owner what is going on and what needs to be done, you haven’t successfully done your job as a veterinarian. You must be able to communicate with a rocket scientists and a redneck. It doesn’t matter what comes through that door, you have to be able to tell it the diagnosis and prognosis in a way they can understand” (Cox Interview). Using terms that veterinarians understand may work for other veterinarians, but that will not work for the majority of clients that come into a clinic looking for answers about their pet (Paul 42). Another significant area of communication is with the technicians and workers that a veterinarian works with and employs. You must be able to communicate with them through the charts and what is written down in which handwriting and clearness is extremely important. During my observation, the technicians spent a good ten minutes trying to decipher the doctor’s handwriting which ended in them having to pull him aside and ask him what exactly he wrote. This took away from time that could have been spent productively with clients. Yates 9 Another example of technician’s communication was after each client visit the doctor would come out of one room and immediately ask which room he was needed in next. All of the information he would need about the animal he was about to see was already written down in the chart in order to stay on top of the workload and pace of the clinic. As Dr. Lane puts it, “Bottom line: Write it down and post it where other staff have to see it and go back to your other interrupted tasks” (Lane 51). This communication helped keep the pace of the clinic up and assist the clients in the fastest possible manner. Lastly, what seemed to be the most crucial part of veterinary literacy is being able to communicate with the animals. By touching the animals, being calm and not afraid, and by speaking kindly, the veterinarian can convey a sense of peace to the animal, even if it happens to be terrified. By touching the patients, the veterinarian can determine what kind of ailment is affecting the animal. The sense of smell is just as important as the senses of touch and sight when it comes to diagnosing a problem with a particular patient. These veterinarians not only use their eyes, ears, and noses to ‘read’ the patient but almost all of their senses. The veterinarians use these senses to see the redness of a cat’s gums. They can smell the rotting bark stuck inside the dog’s mouth. They can feel the mass growing on the side of the rabbit. They can hear the whine of protest when a particularly tender spot is touched. This communication also goes both ways. The veterinarian not only communicates to the animals that everything is going to be fine, but he must also be able to read what the animal is communicating back. This animal communication can come from the Yates 10 animal’s eyes, mouth, voice, or the rest of their body, and the veterinarian must be able to read and interpret whatever the animal may be trying to say. Conclusion The value that Dr. Cox and his team places on workplace literacy is amazingly high in that everyone on his team has to be quite knowledgeable and skilled enough to accomplish each and every one of the literacies that I’ve discussed to their fullest extent. According to these other veterinarians, the literacies stop with writing, reading the owners, and communicating with the clients and technicians. I believe that because of my observation, interview, and experience that the list should include reading the animals, the technologies that veterinarians use, and communicating with the animals as well. So if you are looking for a job in a veterinary clinic, or a career in veterinary medicine, be well aware that the literacies held in the highest regard are writing, reading, technology, and, most importantly, communication with clients and animals. Yates 11 Works Cited Cox, Lynn. Personal Interview. All Animal Hospital, 12 April 2014. Lane, David M. “The writing on the wall.” DVM: The Newsmagazine of Veterinary Medicine. 37.9 (2006): 48-51. Print. O’Sullivan, Frank. “Prescription Writing and Record Keeping Requirements for a Veterinary Practitioner.” Veterinary Ireland Journal. 64.4 (2011): 221-223. Print. Paul, Michael. “You say tomato.” DVM: The Newsmagazine of Veterinary Medicine. 43.11 (2012): 42-43. Print. Pinson, David M. “Writing Diagnostic Laboratory Requisition Form Histories.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 244.4 (2014): 408411. Print.