Shang Society

advertisement

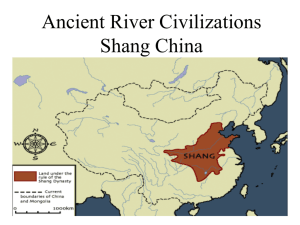

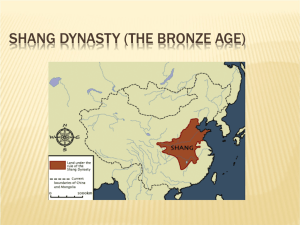

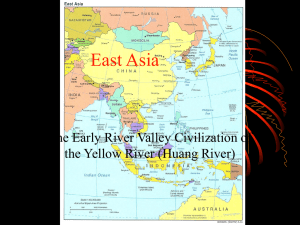

The Hindu Caste System Johnson, Oliver, A. Sources of World Civilization Volume I to 1500. University of California. Prentice Hall. 2000. The differences between systems of social classes; which are necessary components of all complex societies, and a caste system, as a feature of Indian civilization, are a matter of degree, but the degree is great. Four characteristics distinguish the Indian caste system. First, it has the sanction of divine law; second, the castes are sharply separated from each other and movement from one to another is extremely difficult; third, the castes are hierarchically organized, with a social abyss separating the highest from the lowest; and, fourth, castes are hereditary--one is born into the caste in which he must spend his life. The beginnings of the caste system are shrouded in the remote past, but it seems to have developed following the Aryan invasion of India in the second millennium B.C.E. Although references to it can be found in much early literature, its formal elaboration appears in The Laws of Manu, a large compendium of Hindu regulations from which the following selection is taken. These laws were, according to Hindu doctrine, established by the demigod Manu, himself a manifestation of Brahma, so represent divine commands. They divide society into four castes-the priests and scholars (Brahmanas), the nobles and warriors (Kshatriyas), the merchants and farmers (Vaisyas), and the common laborers and servants (Sudras). Although the Brahmanas (who wrote the laws that separated society into castes) were preeminent in prestige and honor, all of the first three castes shared the attribute of being "twice born." Besides their original human first birth, they experienced a "second birth" consisting of their initiation into the mysteries of the Hindu religion. The Sudras were excluded from the "second birth" so could aspire to no higher rank than that of servants to the privileged castes. It should be added that the castes as here described offer an idealized oversimplification of the system, as it has actually existed in India. In fact, there are literally thousands of sub-castes, based on such things as different occupations, area of the country, and so on. Hindus found a religio-moral justification for the caste system. According to the divine law of Karma, an individual in each of his reincarnations is born into a rank and level of society that results from the quality of the life he had lived in his previous incarnation. Thus a member of the Sudra caste has earned that status; his position as a servant is just what he deserves. Furthermore, any attempt to change one's status or to modify the caste system itself would be immoral, as well as a breach of divine law. Two further points should be added. Closely associated with the caste system is a set of regulations governing marriage, the status of women, and family relationships in general. Also, it should be mentioned that a substantial portion of the population of India does not fit into any of the four castes. These are the outcasts or "untouchables" who rank far below the Sudras-indeed, are often treated with less respect than animals. Egyptian Social Structure Egyptian society was structured like a pyramid. At the top were the gods, such as Ra, Osiris, and Isis. Egyptians believed that the gods controlled the universe. Therefore, it was important to keep them happy. They could make the Nile overflow, cause famine, or even bring death. Social mobility was not impossible. A small number of peasants and farmers moved up the economic ladder. Families saved money to send their sons to village schools to learn trades. These schools were run by priests or by artisans. Boys who learned to read and write could become scribes, then go on to gain employment in the government. It was possible for a boy born on a farm to work his way up into the higher ranks of the government. Bureaucracy proved lucrative. The Egyptians also elevated some human beings to gods. Their leaders, called pharaohs, were believed to be gods in human form. They had absolute power over their subjects. After pharaohs died, huge stone pyramids were built as their tombs. Pharaohs were buried in chambers within the pyramids. Because the people of Egypt believed that their pharaohs were gods, they entrusted their rulers with many responsibilities. Protection was at the top of the list. The pharaoh directed the army in case of a foreign threat or an internal conflict. All laws were enacted at the discretion of the pharaoh. Each farmer paid taxes in the form of grain, which were stored in the pharaoh's warehouses. This grain was used to feed the people in the event of a famine. Noble Aims Right below the pharaoh in status were powerful nobles and priests. Only nobles could hold government posts; in these positions they profited from tributes paid to the pharaoh. Priests were responsible for pleasing the gods. Nobles enjoyed great status and also grew wealthy from donations to the gods. All Egyptians — from pharaohs to farmers — gave gifts to the gods. Middle classes Soldiers fought in wars or quelled domestic uprisings. During long periods of peace, soldiers also supervised the peasants, farmers, and slaves who were involved in building such structures as pyramids and palaces. Below the soldiers on the social ladder were the scribes. Scribes were learned persons, who could read and write and typically performed government jobs like tax collection. Below the scribes were the merchants and store keepers who bought and sold goods. Skilled workers such as craftspersons filled the next level of the social hierarchy. Craftspersons made and sold jewelry, pottery, papyrus products, tools, and other useful things. Naturally, there were people needed to buy goods from artisans and traders. The Bottom of the Heap At the bottom of the social structure were farmers and slaves and servants. Slavery became the fate of those captured as prisoners of war. In addition to being forced to work on building projects, slaves toiled at the discretion of the pharaoh or nobles. Farmers tended the fields, raised animals, kept canals and reservoirs in good order, worked in the stone quarries, and built the royal monuments. Farmers paid taxes that could be as much as 60 percent of their yearly harvest — that's a lot of hay! Mesopotamian Social Structure Slaves were the bottom of the social hierarchy, but were generally treated well. All slaves were identified by their specific haircut. Had no rights, were owned by the wealthy, merchants, some even worked for commoners and worked in the temples, the palace, or on farms. Slaves were obtained as prisoners of war, or people who couldn’t pay debts. Sometimes they were offered as payment for a relative’s debt. The civilizations of Mesopotamia would raid the hills for slaves from ‘Hill People’ tribes Law didn’t protect them, but attributed what rights they had to their owner. (e.g. - if the slaves arm was broken, the owner would receive compensation) The Commoners-The laboring lower-class of the kingdom-85% were in farming. The specialized tradesmen (nonfarmers) were paid uniform wages from the surplus collected from the farmers as taxes. Women enjoyed more rights than in other social orders. They had close family ties, but weren’t educated. Boys were taught their father’s trade, while girls were taught to care for the home and children by their mother. Merchants and Artisans invented Cuneiform to document trade deals. They traded ideas and products throughout the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, taking caravans as far as Egypt, Cyprus, and Lebanon. Merchants produced the wealth that made civilization possible. Merchants would lead groups with barley and textiles to Asia Minor, returning with timber, stone and metal. Artisans worked raw materials into tools, weapons, and jewelery. To keep track of trade, they invented calendars that were based on the cycle of the moon (included 12 months, leaps years, and a zodiac). The Scribes were the educated class, sons of the wealthy. They were able to read and write, worked for the palace, the government, the army, merchants, or set up their own business as public writers. Scribes were nearly always men. They had to undergo training and complete a specific program to be called a scribe. The Priests were the upper-class of society. They were influential because of the importance of religion and their relationship with the gods. They controlled the distribution of land to farmers and crops to workers and ran the school. They were considered the ‘doctors’ of the time. The King was the pinnacle of the social order. They were ‘divinely ordained humans’ as believed by the Sumerians, or literal ‘gods on earth’ as the Assyrians believed. The word of a king was law. The King was generally head of the army. They were sometimes also priests. Shang Dynasty Society Shang Society From what has survived archaeologists and historians have learned much of the Shang culture. The Shang were skilled workers in bone, jade, ceramics, stone, wood, shells, and bronze, as proven by the discovery of shops found on the outskirts of excavated palaces. The people of the Shang dynasty lived off of the land, and as time passed, settled permanently on farms instead of wandering as nomads. To guard against flooding by the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, the ancient Shang developed complex forms of irrigation and flood control. The farming of millet, wheat, rice, and barley crops provided the major sources of food, but hunting was not uncommon. Domesticated animals raised by the Shang included pigs, dogs, sheep, oxen, and even silkworms. Like many other ancient cultures, the Shang created a social pyramid, with the king at the top, followed by the military nobility, priests, merchants, and farmers. Burials were one way in which the social classes were distinguished. The elite were buried in elaborate pit tombs with various objects of wealth for a possible use in the afterlife. Even an elephant was found among the ruins of an ancient tomb. The people who built these tombs were sometimes buried alive with the dead royalty. The lesser classes were buried in pits of varying size based on status, while people of the lowest classes were sometimes even tossed down wells. Beginning to Believe All of the classes however had one thing in common — religion. The major philosophies to later shape China — Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism — had not yet been formed. Folk religion during the Shang dynasty was polytheistic, meaning the people worshipped many gods. Ancestor worship was also very important to the Shang. It was thought that the success of crops and the health and well being of people were based on the happiness of dead ancestors. If the ancestors of a family were pleased, life for that family would be prosperous. If the spirits were not pleased however, great tragedies could occur. In addition, the god worshipped by everyone during the Shang dynasty was Shang Ti, the "lord on high." Shang Ti was believed to be the link between people and heavenly beings. The souls of ancestors, it was thought, visited with Shang Ti and received their instructions from him. It was therefore very important to make sure that Shang Ti was happy. This was done with various rituals and prayers, offerings, and sometimes even human sacrifices. The last king of the Shang dynasty, Shang Chou, was a cruel man known for his methods of torture. The dynasty had been weakened by repeated battles with nomads and rivaling tribes within China. Shang Chou was ousted by the rebel leader Wu-wang in 1111 B.C.E.