Naloxone as OTC Drug

advertisement

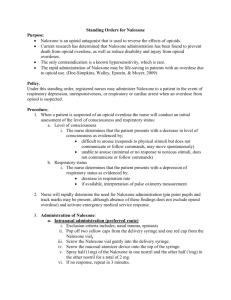

PLEASE NOTE: THIS RESOLUTION WILL BE DEBATED AT THE 2013 COUNCIL MEETING. RESOLUTIONS ARE NOT OFFICIAL UNTIL ADOPTED BY THE COUNCIL AND THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS (AS APPLICABLE). RESOLUTION: 38(13) SUBMITTED BY: Larry Bedard, MD, FACEP Richard Bukata, MD, FACEP Jerome Hoffman, MD, FACEP James Mitchiner, MD, FACEP SUBJECT: Naloxone as an Over the Counter (OTC) Drug PURPOSE: Adopt a policy in support of Naloxone becoming available as an OTC drug and promote education and safeguards for its use. FISCAL IMPACT: Costs could potentially exceed $100,000 depending on the scope of the effort and the development of the public relations campaign and materials. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 WHEREAS, Accidental drug overdose accounted for more than 22,400 deaths in 2005; and WHEREAS, since 2005, accidental drug overdose-from both legal and illegal drugs- is the second leading cause of accidental deaths; and WHEREAS, Naloxone is a highly effective treatment for narcotic overdose if administered in a timely fashion; and WHEREAS, Naloxone’s only effects are to reverse respiratory failure resulting from an opioid overdose and to cause uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms in the dependent individual; and WHEREAS, Naloxone availability programs in Chicago, Baltimore, San Francisco, and New Mexico have been successfully used to save thousands of lives; and WHEREAS, Naloxone has been available OTC in Italy for many years without problems; therefore be it RESOLVED, That ACEP adopts a policy that Naloxone should be available as an Over the Counter (OTC) drug with appropriate education and safeguards; and be it further RESOLVED, That ACEP promote the availability of Naloxone as an Over the Counter (OTC) drug with appropriate education and safeguards through legislative or regulatory advocacy at the local, state, and national levels. Background This resolution calls for the College to endorse and support the reclassification of Naloxone’s prescription drug status to an over-the-counter drug. Naloxone (commonly referred to as Narcan) is an opioid receptor antagonist currently approved for use by injection only for the reversal of opioid overdose and for adjunct use in the treatment of septic shock. It is used mainly in emergency departments and in ambulances by trained medical professionals. Prescribing Naloxone is considered an off-label use of the drug. Naloxone has no effect on non-opioid overdoses. Resolution 38(13) Naloxone as an Over The Counter (OTC) Drug Page 2 As the public health concern regarding the prevalence of drug overdose continues to grow, legal and medical stakeholders are working to find safe, cost-effective solutions to combatting one of the leading causes of unintentional injury and death in the U.S. According to a DHHS’SAMHSA survey, there were approximately 2.3 million people in the United States with opioid dependence as of 2009. More people died from prescription opioid overdoses than from all other illicit drugs combined. Death from an overdose typically occurs one to three hours after taking the drug, frequently occurs in the presence of other people, and medical help is often not sought or is sought too late. Fear of police involvement has been a barrier to calling 911 during an overdose event. Since the 1990s, the accessibility to Naloxone has expanded slowly to reach physicians, clinics, and emergency services providers. A number of community-based programs have offered opioid overdose prevention services to persons who use drugs, their families and friends, and service providers. Yet, barriers to intervention and overdose reversal still existed. Other approaches began to be considered. In the late-1990s, a number of these programs started providing Naloxone hydrochloride to reverse the potentially fatal respiratory depression caused by overdose of heroin and other opioids. In 1995, some European countries began to provide prescription Naloxone for injection drug users. Underground programs first distributed Naloxone in 1999 in the United States, first in Chicago, then in San Francisco. A pilot study that included opiate education and Naloxone prescription was sponsored in 2001 by the San Francisco Department of Public Health. New Mexico was the first state to encourage prescribing take-home Naloxone to heroin-injecting patients, and implemented legislation to provide medical liability protection for those prescribing Naloxone. As of July 2012, eight states have Naloxone prescribing laws; seven states provide criminal prosecution immunity for licensed health care professionals for prescribing, dispensing, or distributing Naloxone to a layperson; three states provide physicians with civil liability immunity; seven states provide criminal prosecution immunity for laypersons administering Naloxone; and two states provide civil liability for laypersons. In 2013, Colorado enacted a law providing civil and criminal immunity for licensed health care providers and for laypersons (with education of the layperson strongly encouraged), and Maryland passed a bill that allowed laypersons receiving a certificate (after educational training) to administer Naloxone, and protected physicians from discipline when prescribing to those individuals. On April 12, 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in collaboration with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, National Institutes of Drug Abuse, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), held a scientific workshop to initiate a public discussion about the potential value of making Naloxone more widely available outside of conventional medical settings to reduce the incidence of opioid overdose fatalities. At this meeting, the FDA discussed ways to expand access to Naloxone through the development of new formulations (would require a bioequivalence study), or making Naloxone approved for use over the counter (additional clinical data would be needed). Other issues discussed at the April 12 meeting, included: (1) the need for easier access to Naloxone; (2) that there needs to be better data on whether Naloxone is effective in saving lives; (3) the relatively short half-life of Naloxone compared to some longer-acting opioid formulations; (4) that after Naloxone is administered, it is important to seek immediate medical attention; and (5) the concern that increasing the overall availability of Naloxone might lead to increased drug use by giving a false sense of security. One speaker stated that such interventions do not necessarily lead to more risky behaviors; instead, the results are dependent on the prevention strategy, the target of the strategy, individual characteristics, and the larger social context. The meeting ended with each of the federal partners expressing willingness to work with interested manufacturers and developers to further explore the best uses of Naloxone to prevent opioid overdose deaths. No change has been made to date and, significant financial barriers and limited use contribute to the low likelihood of a generic pharmaceutical company approaching the FDA to request that this drug be reclassified. Further, a declining number of health plans pay for OTC drugs, which is another barrier to change. Some researchers are urging that the public health community urge the Administration – White House, NIDA, CDC, and other agencies – to support FDA re-classification of Naloxone to non-prescription status. Other papers have stressed the importance of layperson education about Naloxone use, including recognizing symptoms of overdose, the importance of calling 911, rescue breathing, and administration of the opiate antagonist. The February 17, 2012 issue of “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” (MMWR), reported on communitybased opioid overdose prevention programs providing Naloxone. The report was based on an online survey conducted by the Harm Reduction Coalition, a national advocacy and capacity-building organization, of 50 Resolution 38(13) Naloxone as an Over The Counter (OTC) Drug Page 3 programs known to distribute Naloxone in the United States. A total of 48 programs completed the survey. The report states that the findings suggest that distribution of Naloxone and training in its administration might have prevented numerous deaths from opioid overdoses. The report states that the report findings are subject to limitations because the data are based on unconfirmed self-reports from the responding programs, and due to incomplete data collection on numbers of persons trained in Naloxone administration , the number of overdose reversals involving Naloxone, and the number of untreated opioid overdoses that survived without Naloxone administration. The report also states that 43.7% of the responding programs had problems obtaining Naloxone related to cost and drug shortages. Price increases of some formulations of Naloxone appear to restrict current program activities and the possibility of new programs. The report states that economic pressures on state and local budgets could decrease funding of opioid overdose prevention activities. The report recognizes that during the same time, various other prevention measures have been adopted, such as opioid prescribing guidelines, prescription drug monitoring programs, and prescription drug take-back programs. In October 2012, the Network for Public Health Law provided a webinar on issues related to take-home Naloxone for opioid overdose including legal/regulatory barriers to Naloxone access. Some possible solutions listed included removal of civil and criminal penalties for prescribers and administrators of Naloxone with Naloxone access laws and Good Samaritan laws. In June 2013, the CDC issued a health advisory regarding overdose with a synthetic opioid, acetyl fentanyl. Acetyl fentanyl is not available as a prescription drug in the United States. It is up to five times more potent than heroin. It is believed that Naloxone will have the same reversal effect as it does for fentanyl and other synthetic opioids; however, larger doses of Naloxone may be required to reverse the opioid induced respiratory depression because of the higher potency of fentanyl and acetyl fentanyl compared to heroin. The CDC advised that emergency departments and emergency medical services ensure they have adequate Naloxone available, as some services have run out of Naloxone in the face of increased numbers of overdoses and administering higher doses of Naloxone in a short period of time. Potential Benefits of OTC Naloxone Naloxone does not produce a high nor has it been found to be an addictive drug. Naloxone has rare side effects and associated risks. OTC availability would allow for a wider coverage of the at-risk populations, whereas community-based interventions only reach the population seeking these services. There is ample time to administer Naloxone as overdose death occurs 1-3 hours after the drug is taken. Many people who overdose die before a doctor or emergency services arrive. Naloxone can be administered intra-nasally. Potential Risks of OTC Naloxone Expanding the reach may compromise control of effective training programs. Study findings describe reported fears associated with bystanders administering Naloxone: precipitating an acute withdrawal, suicidal intent by recipient, and/or fear of killing the recipient. Surrounding bystanders may be untrained and/or intoxicated themselves. Under-reported unsuccessful use may be attributed to the avoidance of calling emergency services in fear of legal consequences. Uninformed bystanders may administer Naloxone and forego needed medical attention. ACEP Strategic Plan Reference Goal 1 – Reform and Improve the Delivery System for Emergency Care Objective B – Promote quality and patient safety, including the development and validation of quality measures. Tactic 5 – Promote legislative proposals that seek to reduce/eliminate prescription drug abuse. Tactic 6 – Advocate for legislation to reduce/eliminate drug shortages. Resolution 38(13) Naloxone as an Over The Counter (OTC) Drug Page 4 Goal 2 – Enhance Membership Value and Member Engagement Objective B – Provide robust educational offerings including novel delivery methods. Tactic 8 – Begin development of the following new education/CME activities:…opioid educational package. Fiscal Impact Costs are difficult to estimate and depend on whether other organizations would be willing to provide funding for a large-scale effort to develop a coalition of physicians, patients, and drug companies and create a public relations campaign to garner public support . Costs could potentially exceed $100,000 for ACEP, depending on the scope of the effort and the development of the public relations campaign and materials. Prior Council Action None Prior Board Action None Background Information Prepared By: Barbara Tomar Federal Affairs Director Reviewed By: Marco Coppola, DO, FACEP, Speaker Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, Vice Speaker Dean Wilkerson, JD, MBA, CAE, Council Secretary and Executive Director