Study Elementary School cooperative teaching

advertisement

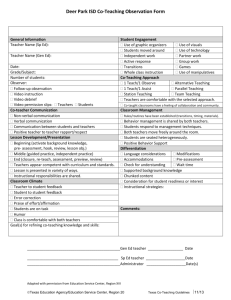

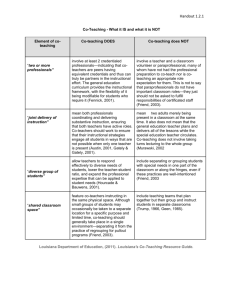

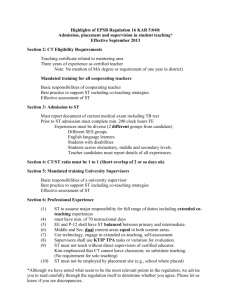

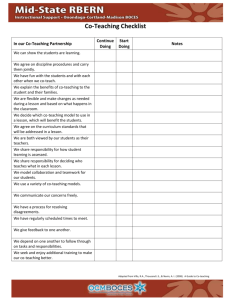

1 PROGRAM EVALUATION Study Elementary School Cooperative Teaching Program for Inclusive Practices Program Evaluation Melissa Ainsworth Lauran McMichael Peg Weimer George Mason University November 27, 2013 Submitted to Dr. Lori Bland 2 PROGRAM EVALUATION Study Elementary School Cooperative Teaching Program for Inclusive Practices Program Description Introduction The subject of this evaluation is Study Elementary School’s implementation of a modified version of the Stetson co-teaching model. With the support of the local school district, the administration at Study Elementary School has modified and implemented the Stetson coteaching model in an effort to create a more inclusive learning environment, improve the utilization of staff, maximize instructional time, and improve the overall quality of instruction. To investigate the effectiveness of the implementation of the model, and inform improvement and further development of the program the principal has requested a formative evaluation. Study Elementary School is a small suburban community school located in Loudoun County, Virginia. It was built in 1966, on the heels of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” program, which emphasized education as a priority, and included the establishment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 (Guilford, 2013; Faltis, 2001; Ferguson, 2007). The community has evolved from its origins as a middle class, all white suburb of Washington, DC, to become a diverse, low income, transient community. Study Elementary, a Title I school, currently serves approximately 519 children in kindergarten through fifth grade. The vast majority of students are non-white, with 70% of the student body being Hispanic. Additionally, 63% of the student population at Study School is economically disadvantaged, 54% are English language learners and 8% receive special education services (Guilford, 2013). Study Elementary School has been identified as underperforming by the Virginia Department of Education, because it failed to meet Federal Annual Measurable Objective (FAMO) goals in the 2011-2012 and 2012- 2013 school-years, 3 PROGRAM EVALUATION and is labeled a Focus School. As a Focus School, Study School is subject to a school improvement plan that is closely monitored by the Virginia Department of Education and Loudoun County Public Schools (LCPS). Historically, push-in and pull-out models have been used at Study School to address the educational needs of special education students, English language learners, and struggling readers. In recent years every classroom had the support of a reading specialist, special education teacher, or ELL teacher for a minimum of a one hour reading block daily. The specialists worked with struggling readers in small groups to tailor reading instruction to each student’s specific needs. In cases where it was appropriate, some students were pulled out of the classroom during the reading block for more specific remediation. Additionally, special education and ELL teachers implemented both push-in and pull-out models to support students in content and math. All students reading below grade level had access to, and support from the appropriate specialist. In an effort to create a more inclusive learning environment, improve the utilization of staff, maximize instructional time, and improve the overall quality of instruction, Study School has moved to a full inclusion co-teaching model. Description of the Program The Study School co-teaching program is a modified version the Stetson co-teaching model. Stetson & Associates, Inc. is a Texas-based educational consulting firm that was created in 1987. Their mission is “to support administrators, teachers, and parents in their efforts to enable every student to be engaged, included, high-achieving, and prepared for adulthood.” (Stetson, 2013). The Stetson co-teaching model was originally developed to promote inclusive teaching practices for special education classrooms, with the intent of providing instruction to 4 PROGRAM EVALUATION special education students in the least restrictive environment possible. Stetson framework is intended to help schools develop a change in the way students with special education needs are educated and viewed by all employees, and how students with disabilities are treated. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) supports inclusive practices through its requirement that “to the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are nondisabled; and that special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child such that education in regular classes, with the use of supplementary aids and services, cannot be achieved satisfactorily” (IDEA, 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1412, ). The true Stetson model is based on collaboration between a special education teacher and a general education teacher to teach all students in the general education setting, where possible. Both are equally responsible for all students and all phases of instruction, including planning and implementing lessons and assessing students’ learning (Stetson, 2013). The Stetson model addresses three aspects of the collaborative teaching relationship; personal commitment to the role, interpersonal relationships, including role clarity and teaching style issues, and procedural considerations, such as time for planning and how to build a schedule that results in support instead of stress. The model is implemented through three phases that include an administrative overview, team training, and technical assistance (Stetson Online Learning, 2013). Team training provides: ● A definition of inclusive education ● Instructional strategies for diverse learners in the general education classroom ● Three staffing models to assure that students and teachers receive the support they need 5 PROGRAM EVALUATION ● A process for scheduling that makes the best use of resources ● Five strategies to improve paraeducator services ● A peer assistance and peer tutoring program. Like the Stetson model, the Study School model includes collaboration between the co- teachers in every phase of instruction. The primary difference between the modified co-teaching model being implemented at Study Elementary and the Stetson model is the use of ELL teachers, reading specialists and teaching assistants as co-teachers. Every classroom has a licensed general education teacher, but the co-teacher could be any of the above. The rationale for this modification is the specific student population, and staffing constraints. The majority of students at Study School are second language learners, and many struggle with reading. Relatively few are special education students. Historically, many ELL students, struggling readers and special education students were pulled out of the classroom to work with the appropriate specialist. The Stetson model is applied in this case to provide more inclusive instruction for all students. The use of teaching assistants in lieu of licensed teachers is driven by staffing constraints. It would be prohibitively expensive to have two licensed teachers in every classroom (Study School Professional Development, 2013). Study School has participated in the first two phases of implementation; administrative overview and team training, and has started the technical assistance phase. Key components of both the Stetson model and the Study School program include: ● Inclusive practice ● Training ● Scheduling ● Co-teacher staffing model (general education teacher and co-teacher) 6 PROGRAM EVALUATION ● Collaboration ● Co-planning ● Co-teaching ● Shared responsibility for student outcomes (Stetson, 2013; Study School Professional Development, 2013). Stakeholders. There are numerous stakeholders who are impacted by the co-teaching program at Study School. The client is the school administration. As the leaders of a focus school, they have a vested interest in ensuring that the educational needs of all students are met. The school is heavily scrutinized, and in danger of facing further sanctions, including an instructional audit by the state, if performance does not improve. This program is listed as part of the school improvement plan. The administration wants to carefully monitor the implementation of the program to ensure the greatest possibility of success. The list of other stakeholders includes: ● Students and their families, who want the best possible educational opportunities; ● Teachers and teaching assistants, who are currently subject to school improvement sanctions, and are responsible for implementing the program, while ensuring positive student outcomes; ● Loudoun County Public Schools district administrators, who evaluate school programs and are ultimately responsible to the state; and ● The district special education department, who touted the Stetson model, and are advocates of inclusion (Loudoun County School Board, 2011). In addition, the wider audience includes other schools in the district that may be considering, or are required to implement the Stetson model. In its 2011-2012 annual report to the school 7 PROGRAM EVALUATION board, the Loudoun County Public Schools Special Education Advisory Committee (SEAC) recommended that LCPS “continue to demonstrate their commitment to inclusive practices, inclusive messages, and other practices in order to continue the promotion of a positive cultural change in the way students with special education needs are viewed by all employees and how students with disabilities are treated. LCPS has invested in the Stetson Inclusive Practices approach and SEAC is supportive of continued expansion of this framework” (Loudoun County School Board, 2011, p. 9). Theory of Action. If Study School is to use a co-teaching model to provide more inclusive instruction for all students, then teachers’ roles have to change. Teachers will need team training that provides instructional strategies for diverse learners in the general education classroom, staffing models to assure that students and teachers receive the support they need, a process for scheduling that makes the best use of resources, strategies to improve teaching assistant services, peer assistance, and peer tutoring program. Once teachers receive sufficient training, they will be reallocated into co-teaching teams by the administration. The administration will assign the co-teaching teams to classes based on the dynamics of the students in each class. Collaborative planning time will be built into teachers’ schedules allowing team members time to design lessons that will reflect the expertise of each co-teacher. Lessons reflecting the expertise of each co-teacher will be implemented together, so students will have access to a greater variety of teaching strategies without leaving the classroom for instruction. Increased instructional time and exposure to a greater variety of teaching strategies will meet the learning needs of more individual students in an inclusive classroom. When students’ individual learning needs are met, student learning will improve. An increase in student learning will be 8 PROGRAM EVALUATION reflected in improved student outcomes on state tests. The Theory of Action is summarized in Figure 1. Figure 1 Theory of Action If Then If we use a co-teaching model Teachers roles will to change If teachers’ roles are changing Teachers will need training If teachers have training If teachers are in co-teaching pairs Teachers can be reallocated into co-teaching pairs Teachers need co-planning time If teachers need co-planning time Co-planning time will have to be scheduled If co-planning time is scheduled Teachers will plan together If teachers plan together Teachers will collaboratively design lessons If teachers collaboratively design lessons Teachers will know their responsibilities in implementation and implement lessons together that reflect the expertise of each co- teacher Students will have access to a greater variety of teaching strategies without leaving the classroom for instruction Students’ individual learning needs are more likely to be met, and transition times between classrooms will be reduced or eliminated Instructional time will increase If lessons reflect the expertise of each coteacher, and teachers are implementing lessons together If students have greater opportunity to accesses a variety of teaching strategies without leaving the classroom for instruction If transition times are reduced or eliminated If students’ individual learning needs are met, and instructional time increases If student learning improves Student learning will improve Student outcomes on state tests will improve Theory of Change. In order to ultimately improve student scores on state tests, a coteaching model will be adopted. Once teachers are trained in how to plan and teach as a team and are provided with models of a variety of co-teaching arrangements, they will be able to implement co-teaching in their classroom. Teachers will also need to be supported by the school administration in the form of adequate co-planning time. Once teachers are implementing a co- 9 PROGRAM EVALUATION teaching model in their classroom, students will benefit from increased individualized instruction since each of the teachers will be utilizing their own strengths and expertise. Since students are receiving increased individualized instruction, their learning needs are being better addressed which should result in increased student scores on state tests. The Theory of Change is summarized in figure 2. Figure 2 Theory of Change: How will student scores on state tests improve? Co-Teaching Implementation Teachers will be trained to work and plan together Teachers will be trained in co-teaching models Co-teachers Utilize their individual strengths and expertise when planning lessons Provide more individualized instruciton for students in their classroom Students Have their indivdiualized learning needs met Improve their scores on state tests A logic model for the program was developed from the Theory of Action and the Theory of Change (see Appendix A). Literature Review For many schools and school districts, rising numbers of students who are English language learners and students who require special education delivered in the general education classrooms combined with increasing pressure from state standards as proscribed by the No 10 PROGRAM EVALUATION Child Left Behind Act (2000) have led administrators to look for creative solutions to making sure that all students make progress in the general education curriculum. The number of English language learners in schools has risen by 57 % in the past ten years (McGraner & Saenz, 2009) and there has been approximately a 30 % increase in students with disabilities spending 80 percent of their time in general education classes over the past 20 years (U. S. Department of Education, NCES, 2012). According to Cook and Friend (1995), putting two professionals in one classroom in order to deliver qualitatively and substantively different instruction to a diverse group of students was in large part due to an increase in mainstreaming students with special needs into general education settings. Co-teaching is one of those solutions that educators and administrators turn to in helping to ameliorate the challenges such diverse classrooms pose (Mastropieri, Scruggs, Graetz, Norland, Gardizi & McDuffie, 2005; Murawski & Swanson, 2001). The salient element of coteaching is that it involves two licensed professionals, traditionally a general education teacher and a special education teacher although other variations might involve a general education teacher and a related service provider such as a speech/language therapist (Cook & Friend, 1995). Whatever the configuration, the intent of a co-teaching model is to combine the specific expertise of two professionals to make the instruction substantively different so that a diverse group of students, originally and traditionally special education students, can all make progress in the general education classroom (Friend, Cook, Hurley-Chamberlain & Shamberger, 2010). Hepner and Newman (2010) and Austin (2001) report pervasive teacher satisfaction with the co-teaching model, despite a reported lack of training in specific co-teaching strategies. The keys to attaining satisfaction with a co-teaching model involve open communication between coteaching partners and a shared educational philosophy (Keefe, Moore & Duff, 2004; Walther- 11 PROGRAM EVALUATION Thomas, 1996; Cook and Friend, 1995). Likewise, schools that embark on co-teaching must demonstrate a commitment to it by providing adequate direction to co-teaching pairs in what is expected as well as listening to teachers and students about their experiences in co-taught classroom (Keefe & Moore, 2004). According to Stetson and associates, co-teaching is defined as two certified teachers (one special education and one general education teacher) equitably and appropriately sharing classroom roles and responsibilities “on behalf of all the students they share in an inclusive classroom” (Stetson & Ass., 2009). Beyond that, there is little consensus on what constitutes effective co-teaching. In a review of literature conducted by Weiss and Ainsworth (2013), the authors discovered that there was much literature published on the different models of co-teaching, such as one-teach-one assist or station-teaching, but very little on how, or if the learning experience for students is substantively different in a co-taught classroom from that of a traditional classroom model with only one teacher. Murawski & Swanson (2001) reported that although co-teaching is touted as an effective instructional delivery model, there is very little empirical data to back it up. Out of 89 articles the authors found for their meta-analysis, only six met their inclusion criteria and only three of the studies included effect sizes. Across the co-teaching literature there are common themes in the benefits found in coteaching situations as well as common themes in the challenges faced by co-teaching teams. Some benefits found in the literature include increased individualized attention for students, diversity in teaching strategies, professional satisfaction, professional growth and personal support. Some of the challenges that co-teachers face as reported in the literature include scheduling co-planning time, scheduling students, case load concerns especially for special education teachers adequate administrative support (Walther-Thomas, 1997) and equal academic 12 PROGRAM EVALUATION content knowledge between co-teachers (Mastropieri et al., 2005). Co-teacher compatibility was also identified in the literature as a major factor in either a successful co-teaching situation or a stressful one (Mastropieri et al.; NEA Today, 2008). Need for Evaluation Study School has been identified as underperforming by the Virginia Department of Education, and is labeled a Focus School. Focus schools are subject to school improvement plans that are closely monitored by the Virginia Department of Education and the local school district. Should Study School continue to fail, further sanctions will be forthcoming, including instructional audits and possible loss of Title I funding. As the leaders of a focus school, the administrators have a vested interest in ensuring that the educational needs of all students are met, and the students in those sub-groups that did not meet the FAMOs have every possible opportunity to achieve. The Co-teaching model was recently implemented at Study School with the long-term goal of improving overall school performance, and moving the school out of school improvement status. As a newly implemented program, it is important to the stakeholders that a formative evaluation guides the progression of the program and provides suggestions for improvement. The administration wants to carefully monitor the implementation of the program to ensure the greatest possibility of success. Evaluation Questions Because this evaluation is formative in nature, and focuses on the implementation of the program, the evaluation questions seek to determine whether the program is being implemented with the spirit intended and to the letter of the design. Two questions are the central focus of the evaluation: 13 PROGRAM EVALUATION 1. Are the cooperative teaching teams implementing the program as intended by planning together, teaching together and assessing together? If not, why not? What are the barriers, and how can they be reduced or eliminated? This question is important because the rationale for the program is founded on better utilization of human resources to provide an inclusive learning environment. Before the effectiveness of the program can be evaluated, it should be determined whether effective implementation is occurring, and the situation should be remediated if it is not. 2. Are teaching assistants qualified to assume the responsibilities of a co-teacher? This is important because the ultimate goal is to provide the best possible educational opportunities for all students. If teaching assistants are not qualified to perform the responsibilities required of a co-teacher, it is unlikely that this goal will be attained. Methods This section will describe the documents and instruments used in data collection and will describe the procedures used in analyzing the documents themselves and the results of the instrument. Data Collection Documents. Two documents were analyzed for usability to inform the evaluators, school-based administrators, teachers, and teaching assistants about the intended practices in implementing the Stetson co-teaching model. The first document, The Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom, written by Stetson and Associates, Inc., in 2006 was retrieved from the Stetson & Associates website at http://stetsonassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Assessment-of-Collaborative- 14 PROGRAM EVALUATION Teaching.pdf. This is an assessment tool outlining the best practices in rubric format that should be implemented in using the Stetson co-teaching model to promote inclusive teaching practices for special education classrooms, with the intent of providing instruction to special education students in the least restrictive environment possible. The best practices are divided into six categories that include: setting/support, partnership, instruction, communication, planning, and ancillary issues. The best practices in the setting and support include: a collaborative practice providing seamless or invisible support to special needs children in an inclusive classroom; partners who acknowledge dual ownership of all students; and arrangement of classroom space, materials, and supplemental resources that support both adults and all students in the inclusive classroom. The best practices in partnership include team members who: introduce an equitable partnership to the students; discuss roles and responsibilities of the collaborative teaching partnership; both assist any student who needs academic or behavioral assistance in the class; and acquire new collaborative teaching skills by working closely with his/her partner. The best practices in instruction include: team members who use a variety of highly effective instructional strategies; team members who discuss instructional delivery styles relative to individual strengths; instructional activities and strategies that are reflective of their students’ skills, interests, motivation, and learning styles; instructional accommodations and curricular modifications that are appropriately applied to all students requiring accommodations and modifications; conversations to discuss instructional routines, procedures, and requirements relative to student success and effective collaborative teaching; and multiple assessments and grading strategies reflecting student needs for differentiated assessment. The best practices in communication include: open communication that is encouraged by each team member; discussion and development of classroom routines, 15 PROGRAM EVALUATION procedures, and processes; discussion and development of a mutually agreed upon classroom management system isolating rules, expectations, and consequences; scheduled periodic reflection of the collaborative teaching experience to review and modify support for both students and teachers; open sharing of professional rules, beliefs, concepts, or procedures that are non-negotiable; and open discussion of possible and predictable issues that may arise in a classroom that is collaboratively taught. The best practices in planning include: regularly scheduled collaborative planning time between special education and general education team members for the following: instructional and partnership needs; outlines of individual roles and responsibilities; accommodations and curricular modifications to meet the needs of students with disabilities; and academic and behavioral needs of the whole class and individuals requiring attention. The best practices in ancillary issues include team members who mutually agree in how to communicate with parents of students, campus administrators, or supervisors. The document does not identify the professional qualifications of the co-teachers or assumptions about the qualifications of the co-teachers. The second document, The Roles and Responsibilities of Collaborative Teachers: a Decision-Making Exercise written by Stetson & Associates, Inc., 2009 was retrieved from the Stetson website at http://stetsonassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/RolesResponsibilities-of-CoTeachers.pdf. This document is intended to help co-teachers determine how they will divide up and/or share the various responsibilities and roles involved in running a shared classroom. The document consists of an introductory paragraph and a table. In the introductory paragraph, the goal of the document is defined as a tool to help co-teachers divide up the work of running a classroom equitably and appropriately. In this paragraph, a co-teaching 16 PROGRAM EVALUATION situation is defined as two certified teachers who share one classroom and are equally responsible for all students in the class. The table provides a list of roles and responsibilities teachers might commonly encounter in the process of running a classroom. The table has three options of “other” for co-teachers to individualize the document to their own needs. Next to each role/responsibility are the following options which can be checked off to indicate who will be in charge of that particular role or responsibility: general education teacher; special education teacher; shared; other (para-educator, volunteer, other). The roles and responsibilities specified in the table cover aspects of lesson planning, attending to accommodations for individual students, gathering materials, delivery of instruction, assessment, upkeep of various forms of paperwork, communication with parents, behavior interventions and general classroom management issues. Pre-existing Data. Data were collected from three documents provided by the Study School administrators in order to determine scheduled planning time, scheduled co-teacher instructional time, and any possible scheduling conflicts. The documents include a staff schedule that delineates the times that co-teachers and classroom teachers share instructional time, a schedule of planning times for co-teaching teams, and a staff calendar that includes weekly grade-level team meetings. All three documents were created by the school administrators. Co-Teacher Questionnaire. The best practices outlined in the Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom document was used to design a questionnaire in Google forms to collect data from the teachers and teaching assistants on their perceptions of the implementation of the modified Stetson program (see Appendix B). The questionnaire designed by the evaluation team was composed of a multiple choice demographics 17 PROGRAM EVALUATION section, three likert-scale sections and one open-ended question section. Section one contained four multiple choice demographics questions pertaining to job title, education, licensure, and structure of co-teacher partnerships. Sections two, three, and four use a likert scale in which a 1 indicates the behavior never occurs, a 2 indicates the behavior occurs infrequently, a 3 indicates the behavior occurs often, a 4 indicates the behavior always occurs. Section two includes seven questions focused on the co-teaching classroom setting and climate. Section three consists of twelve questions pertaining to planning, instruction, and assessment. Section four contains nine questions focused on communication and partnership. In section five there are three open-ended questions that invite respondents to share their thoughts and opinions in a narrative format. Question one is focused on positive outcomes or benefits of the co-teaching model. Question two pertains to perceived challenges or barriers of the co-teaching model. Question three addresses respondents’ perceptions of the professional development provided prior to implementing the co-teaching model. Participants. The questionnaire was delivered electronically to all instructional staff in the co-teaching program, as a link embedded in an email detailing the nature and purpose of the survey. A follow-up email was sent two weeks later. Instructional staff is defined as those individuals tasked with the role of co-teacher in study school. This includes twenty-six classroom teachers, three special education teachers, six English Language Learner teachers, three reading teachers, and thirteen teaching assistants. Responses were submitted electronically and collected in a Google spreadsheet that generated a summary of responses in numeric and graphic formats. Participants were assured of their anonymity. Data Analysis Procedures 18 PROGRAM EVALUATION Analysis of Documents. Two documents were analyzed for usability to inform the evaluators, school-based administrators, teachers, and teaching assistants about the intended practices in implementing the Stetson co-teaching model. In order to analyze the documents the following aspects of the documents were considered: evaluation usability; audience usability; trustworthiness of the information; logic model; evaluation criteria; trends, patterns and consistency. Analysis of Pre-existing Data. The staff schedule, planning time schedule and team meeting calendar were compiled and analyzed to determine the number of hours that were scheduled for each co-teaching classroom for shared instructional time and co-planning, as well as to determine any conflicts that impact planning and instructional time. First a spreadsheet was created to compile the data from the planning and instructional schedules. The total number of scheduled hours per week for planning, and the total number of scheduled hours per week for shared instructional time were calculated for each co-teaching classroom. Next, the planning schedule, instructional schedule and the team meeting schedule were cross-compared to determine any conflicts in scheduling. A brief informal meeting with the principal was conducted as a follow-up to determine the protocol for addressing scheduling conflicts and which meetings co-teachers are required to attend. Then, the total hours of co-planning and coinstructional time for each classroom were adjusted to reflect scheduling conflicts. The data in the table was then sorted by number of co-teachers in each classroom (see Appendix C). Finally, a second informal meeting with the principal was conducted to clarify questions about the scheduling rational. The most significant of those questions are closely related: 1) Why do some classrooms have one classroom teacher and one co-teacher that work together for the entire day, while many others have one classroom teacher and two or three co-teachers that come and go 19 PROGRAM EVALUATION during the course of the day. 2) Why do some non-classroom teachers work in multiple classrooms? Analysis of the Co-teaching Questionnaire. The questionnaire contained both quantitative and qualitative data which were collected through Google forms into a Google spreadsheet. The Google spreadsheet generated frequency statistics, pie charts and bar graphs for the responses to each of the questions (see Appendix D). Additional frequency statistics were generated by the evaluators in Excel spreadsheets. The first Excel spreadsheet sorted the data by the type of co-teaching relationship. Three types of co-teaching relationships were identified: one general education teacher and one specials teacher; one general education teacher, one specials teacher, and one teaching assistant; and one general education teacher and one teaching assistant. Frequency subtotals for each question were calculated for each of the three types of co-teacher partnerships. The subtotals for the responses to each question were entered into a second Excel spreadsheet and each question was aligned to the corresponding best practice outlined in the Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom rubric (see Appendix E). Responses skewed towards a positive response (often and always) were highlighted in yellow. Responses skewed towards a negative response (never or infrequent) were highlighted in pink. Open coding was used to analyze the qualitative data collected from the questionnaire. All of the qualitative data was put into a spreadsheet and divided up by participant. Two of the evaluators did the first pass through all the qualitative data pulling out key words, phrases and ideas. Then the third evaluator did another pass through of the data and first pass coding. Further key words, phrases, ideas and questions generated by the coding in the first pass were added. 20 PROGRAM EVALUATION After key words, phrases and ideas were identified, these words were put into another spreadsheet where patterns of responses were identified. Then the evaluators compared the responses from the questionnaire to responses found in the literature on co-teaching. Those responses that are typically found throughout the co-teaching literature were marked as standard responses. Those responses that were unique to the co-teaching model at Study School were identified as unique and were then further analyzed. Results Document Analysis for Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices. The trustworthiness of the Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom can be considered reliable. The document was prepared by Stetson Inc., a Texasbased educational consulting firm that was created in 1987. Their mission is “to support administrators, teachers, and parents in their efforts to enable every student to be engaged, included, high-achieving, and prepared for adulthood.” (Stetson, 2013). The best practices outlined in this document are readable and clearly present the activities to be implemented in the Stetson co-teaching model. The administrators at the study school did not identify any criteria to guide the analysis of this document. However, comparison of the assessment document to the Collaborative Teaching Rubric (The Access Center, 2006 format and edits by @2008, Stetson & Associated, Inc) used by collaborative partners to self-asses and improve their practice indicates the practices outlined in the assessment are aligned to self-assessed practices. The Collaborative Teaching Rubric provides measurement of successful implementation of the program from the beginning and transition stages to the collaborative stages. Measurement occurs in all aspects: the physical arrangement; classroom management; curriculum goals, accommodations, and modifications; curriculum knowledge; assessment; and instructional delivery. 21 PROGRAM EVALUATION External standards are not available for co-teaching, but Cook and Friend (1995) discuss many of the issues and concerns guiding the thinking and planning of professionals as they design and implement co-teaching programs. In this discussion, co-teaching is defined as” two or more professionals delivering substantive instruction to a group of students with diverse learning needs” (para. 6). The definition includes four key components: both professionals are educators, not paraprofessionals, parent volunteers, or older student volunteers in assisting the teachers; the educators deliver substantive instruction; the educators teach a diverse group of students, including students with disabilities; and the instruction is delivered primarily in a single classroom or physical space. The Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices document indicates the educators are to deliver substantive instruction, teach a diverse group of students, including students with disabilities, and deliver instruction in a single classroom or physical space. Cook and Friend also report that “Ideally, co-teaching includes collaboration in all facets of the educational process” (para. 11), which includes collaboratively assessing student strengths and weaknesses, determining appropriate educational goals and outcome indicators, designing intervention strategies and planning for their implementation, evaluating student progress toward the established goals, and evaluating the effectiveness of the co-teaching process. The Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom document outlines best practices for each of these forms of collaboration. The National Education Association (NEA) Policy Statement on Appropriate Inclusion found at http://www.nea.org/home/18673.htm supports and encourages appropriate inclusion. Appropriate inclusion is characterized by the following practices and programs: A full continuum of placement options and services within each option. Placement and services must be determined for each student by a team that 22 PROGRAM EVALUATION includes all stakeholders and must be specified in the Individualized Education Program (IEP). Appropriate professional development, as part of normal work activity, of all educators and support staff associated with such programs. Appropriate training must also be provided for administrators, parents, and other stakeholders. Adequate time, as part of the normal school day, to engage in coordinated and collaborative planning on behalf of all students. Class sizes that are responsive to student needs. Staff and technical assistance that is specifically appropriate to student and teacher needs. (from website, Adopted by the NEA Representative Assembly, July 1994). The Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in Inclusive Classrooms document indicates the Stetson co-teaching best practices include characteristics of appropriate professional development as part of normal work activity and adequate time as part of the normal school day to engage in coordinated and collaborative planning on behalf of all students. Therefore, this document can be used to inform the logic model by defining the activities that need to occur for successful implementation of the modified Stetson co-teaching model. These activities include planning together, teaching together, and assessing together. This document can also be used to inform the theory of change to ultimately improve student learning by adopting a co-teaching model. An underlying assumption of this document is that both partners are licensed teachers. Document Analysis for Assessment of Roles and Responsibilities: A Decision Making Exercise. While this document does not answer either evaluation question, it does 23 PROGRAM EVALUATION provides information about the nature of co-teaching according to the Stetson Model and provides a basis for answering the first evaluation question which addresses whether or not Study School is implementing co-teaching as defined by the Stetson Model. The evaluation audience, defined as administration at Study School, needs to know what the Stetson Model of co-teaching is supposed to look like so that proper determination about the implementation of the model at Study School can be made. This document clearly answers two questions for the audience. First it defines that, according to the Stetson Model, a co-teaching situation should consist of two certified teachers. Secondly, the document provides for the audience a list of roles and responsibilities and when completed by co-teaching pairs, a snapshot of how each pair is dividing up the roles and responsibilities of running their shared classroom. The types of roles and responsibilities listed in the table are consistent with the literature on co-teaching models and the types of roles and responsibilities encountered in running a classroom. One assumption made by the authors of this document is that each teacher within a coteaching pair are equally qualified to carry out any and all of the listed roles and responsibilities and are therefore able to divide the work equitably. Additionally there is an assumption that they should and should want to divide the work equitably. However several of the co-teaching pairs at Study school consist of one certified teacher and one teacher’s assistant who is expected to act as a fully functional co-teacher. This is not a model supported by the Stetson Document which calls for equity in the division of all roles and responsibilities in the classroom. When these two documents are compared there are clear patterns about what co-teaching should entail as well as how it should be implemented. The two analyzed documents support each other in defining how a co-teaching pair should look. 24 PROGRAM EVALUATION Results from Pre-existing Data. The results from analysis of the pre-existing data are summarized in Table 1. Table 1 Average Scheduled and Actual Co-planning and Co-instructional Hours per Week No. of coteachers 1 2 3 Average scheduled planning time 3.64 1.33 1.67 Average lost planning time 0.73 0 0 Average planning time 2.91 1.33 1.67 Average scheduled co-instr. time 23.86 19.79 18.33 Average co- Average coinstructional instructional time lost time 0.09 0.92 2.5 23.66 18.88 15.83 Analysis of the planning schedule indicates that the average scheduled planning time for classrooms with one co-teacher relationship is more than double that of classrooms with multiple co-teaching relationships. Although classrooms with one co-teacher relationship lose nearly one hour per week of planning time due to scheduling conflicts, they still have significantly more actual planning time than those with multiple co-teaching relationships. Classrooms with only one co-teaching partnership have an average of 1.58 hours, or 118% more planning time each week than those with two co-teaching partnership, and an average of 1.24 hours, or 74% more planning time each week than those with three co-teaching partnerships. Analysis of the staff instructional schedule and team meeting calendar indicates that classrooms with only one co-teaching partnership have an average of 4.78 hours, or 21% more co-instructional time per week than those with two co-teaching partnership, and an average of 7.83 hours, or 33% more co-instructional time per week than those with three co-teaching partnerships. Further, classrooms with only one co-teaching partnership lose an average of 0.09 hours of co-instructional time each week due to scheduling conflicts, classrooms with two coteaching partnerships lose an average of 0.92 hours of co-instructional time each week, and 25 PROGRAM EVALUATION classrooms with three co-teaching relationships lose an average of 2.5 hours of co-instructional time each week. Co-Teacher Questionnaire. Quantitative data. The results of the co-teacher questionnaire were summarized in the spreadsheets. Tables provided in this discussion reflect the respondents’ perceptions of how the best practices of co-teaching as defined in the Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom rubric are being implemented. The results in Appendix E reflect the respondents’ perceptions on the roles and responsibilities in the partnerships. Summaries of each category of best practices indicate that all respondents believe the coteaching best practices are being implemented often or always. Table 2 summarizes these findings. Table 2 Average Percentage for Respondents in All Types of Partnerships Best Practice Setting Partnership Instruction Communication Collaborative Planning ALL never infrequent often always 1.5 13.8 42.3 42.3 1.5 13.8 42.3 42.3 2.4 20.6 44.2 32.2 3.5 18.0 37.8 40.5 3.0 42.8 22.5 31.3 Summaries of each category of best practices for co-teaching partnerships consisting of one general education teacher and one specials teacher also indicate the respondents believe all co-teaching best practices are being implemented often or always. Table 3 summarizes the findings. 26 PROGRAM EVALUATION Table 3 Average Percentage for Respondents in 1 Gen Education and 1 Special Education Co-teaching Partnership Best Practice Setting Partnership Instruction Communication Collaborative Planning never 0.0 0.0 1.4 3.5 0.0 1 Gen Ed / 1 Special infrequent often always 10.5 50.0 37.5 10.5 50.0 37.5 15.8 48.4 34.4 16.0 44.8 35.8 34.0 15.8 50.0 Summaries of each category of best practices for co-teaching partnerships consisting of multiple partnerships indicate the members of the partnership believe the best practices in setting, partnership, instruction, and communication are implemented often or always, but the best practice of collaborative planning is implemented infrequently. Table 4 summarizes the findings. Table 4 Average Percentage for Respondents in Multiple Partnerships. Best Practice Setting Partnership Instruction Communication Collaborative Planning never 2.8 2.8 2.2 2.8 0.0 1 Gen / 1 Special / 1 TA infrequent often always 24.8 53.0 19.3 24.8 53.0 19.3 29.0 53.4 15.4 33.3 44.5 25.7 53.0 41.3 5.5 Summaries of each category of best practices for co-teaching partnerships consisting of one general education teacher and one teaching assistant also indicate the members of the partnership believe the best practices in setting, partnership, instruction, and communication are 27 PROGRAM EVALUATION implemented often or always, but the best practice of collaborative planning is implemented infrequently. Table 5 summarizes the findings. Table 5 Average Percentage for Respondents in 1 General Education and 1 Teaching Assistant Coteaching Partnerships. Best Practice Setting Partnership Instruction Communication Collaborative Planning never 4.3 4.3 6.8 4.3 17.0 1 Gen Ed / 1 TA infrequent often always 4.3 8.5 83.0 4.3 8.5 83.0 20.2 20.0 53.2 4.3 12.5 79.3 50.0 8.5 25.0 Detailed analysis of the data representing the best practices in setting and support of coteaching indicates the majority of respondents among all types of co-teaching partnerships believe the support provided to special needs students is often or always invisible and that classroom space, materials, and supplemental resources are arranged to support both the coteachers and the students. Dual ownership of all students is only perceived to be acknowledged often or always by respondents in a co-teaching partnership consisting of one general education teacher and one special education teacher. Table 6 summarizes the findings. 28 PROGRAM EVALUATION Table 6 Percentages of Best Practices in Setting and Support Detailed analysis of the data representing best practices in partnership indicates the majority of respondents among all types of co-teaching partnerships believe both co-teaching partners discuss the roles and responsibilities of the collaborative partnership and are comfortable in assisting any student who needs academic assistance in class often or always. The majority of the respondents in a co-teaching partnership consisting of one general education teacher and one special education teacher also believe partners discuss roles and responsibilities, assist any student who needs behavioral assistance, and that each partner has acquired new professional skills in the collaborative teaching process often or always. Respondents in a coteaching partnership consisting of multiple partnerships believe both partners infrequently or never introduce partnership to students with an emphasis on equity. The majority also believe 29 PROGRAM EVALUATION acquiring new professional skills. Respondents of co-teaching partnerships made up of one general education teacher and one teaching assistant also believe both partners infrequently or never present lessons. Table 7 summarizes the findings. Table 7 Percentages of Best Practices in Partnership Detailed analysis of the data concerning best practices in instruction indicate the majority of respondents in all types of co-teaching partnerships believe co-teachers often or always discuss instructional routines, procedures, and requirements relative to student success. They also believe the partners use a variety of highly effective instructional strategies often or always, apply instructional accommodations and curricular modifications appropriately to all students often or always, and use multiple assessment and grading strategies often or always. The data also indicates the majority of respondents from all types of co-teaching partnerships believe the instructional routines, procedures, and requirements are never or infrequently discussed. In addition respondents in a co-teaching partnership consisting of multiple partnerships believe the 30 PROGRAM EVALUATION partners infrequently or never discuss instructional delivery styles relative to individual strengths. Table 8 summarizes the findings. Table 8 Percentages of Best Practices in Instruction Detailed analysis of the best practices in communication data indicate the majority of the respondents in all types of co-teaching partnerships believe communication is open, welcomed, and encouraged by each partner often or always. They discuss possible issues that may arise. They also believe partners discuss and develop mutually agreed upon classroom management rules, expectations, and consequences often or always. The majority of the respondents in partnerships consisting of multiple partnerships believe time is often or always scheduled for periodic reflection of the collaborative teaching experience. Table 9 summarizes the findings. 31 PROGRAM EVALUATION Table 9 Percentages of Best Practices in Communication In analyzing the data representing the best practices in collaborative planning the majority of the respondents in a co-teaching partnership consisting of one general education teacher and one teaching assistant believe collaborative planning, not just scheduled collaborative planning occurs often or always to collaboratively design lessons to meet instructional partnership needs, accommodations, curricular modifications, academic, or behavioral needs. The majority of respondents in all types of partnerships believe collaborative planning occurs infrequently or not at all to design lessons that meet the accommodations and curricular modifications as well as the behavioral needs of the whole class and individuals. Table 10 summarizes the findings. 32 PROGRAM EVALUATION Table 10 Percentages of Best Practices in Collaborative Planning Analysis of the quantitative data representing the perceptions of the roles and responsibilities in the co-teaching partnerships finds all respondents believe the roles and responsibilities outlined in the Roles and Responsibilities of Collaborative Teachers: A Decision Making Exercise occur often or always with the exception of collaborative planning. Detailed analysis of the results by the type of co-teaching partnership indicates the respondents in multiple co-teaching partnerships believe introducing the partnership to the class and grading of student work never occur or occur infrequently. Table 11 summarizes the findings. Table 11 Percentages of Roles and Responsibilities in Multiple Partnerships Roles and Responsibilities Introducing the Partnership to the class Planning the lesson Grading student work - for all students Grading student work - for students receiving special education services 1 Gen / 1 Special / 1 TA never Infrequent often always 11 56 33 0 0 56 44 0 11 78 11 0 11 78 11 0 33 PROGRAM EVALUATION Design and implementation of assessments are not included in the list of co-teaching roles and responsibilities but the results of the data analysis indicate the collaborative design of assessments is perceived by the majority of respondents to never occur or occur infrequently. Collaborative implementation of assessment is perceived by the majority of the respondents to occur often or always. Collaboration of design and implementation of assessments is perceived to never occur or occur infrequently by the majority of respondents in a co-teaching partnerships consisting of multiple partnerships. Table 12 summarizes the results. Table 12 Percentages of Design and Implementation of Assessments Qualitative Data Analysis. The qualitative data collected by the co-teaching questionnaire was produced in answer to questions about the benefits of a co-teaching situation, the barriers or challenges faced in a co-teaching situation and about the type and amount of professional development co-teachers received prior to implementation of the co-teaching model. In the analysis of the benefits found in the co-teaching model, most of the responses mirrored those aspects generally identified as the benefits of any co-teaching situation. Co-teachers cited increased individual attention to students’ needs, increased student accountability and quicker responses as direct benefits to the students in a co-taught classroom. Additionally, co-teachers reported that they saw benefits to the sharing of ideas, goals, visions, concerns and classroom management responsibilities. Teamwork, respectful partnerships, varied perspectives and having someone else to help with behavior concerns and daily struggles were also cited as benefits to a 34 PROGRAM EVALUATION co-teaching situation. One teacher said, “I feel as though all the students are truly getting the curriculum, due to having two teachers in the classroom. We are able to do a lot of small group instruction to ensure learning is taking place at the pace of each individual student.” Some of the benefits expressed in the qualitative data reflect the unique co-teaching model of Study school. For example, reflective of the use of specials teachers such as reading specialists and English language learner teachers in co-teaching situations, there were several comments about appreciation of being equals in the classroom and enjoying having the opportunity to work with more than just a small group. Additionally half of the general education teachers who responded to the questionnaire and whose co-teaching partner is a teaching assistant felt the need to mention that arrangement specifically. While 2 of the three direct statements were positive in nature, they did identify a division of roles more indicative of a teacher/assistant relationship than that of co-teachers. For example, one general education teacher said, “Because my co-teacher is an assistant, I am able to focus more on planning and teaching rather than the day-to-day tasks.” Another praised her assistant for being “amazing” but went on to specify that “our day is different than most co-teaching models because I do more of the teaching, while she handles the housekeeping aspect of our classroom.” The third general education teacher who specifically mentioned having a teaching assistant in the co-teaching role questioned the validity of the model saying “I can’t see how having a teaching assistant as the co-teacher fits the model. They are not paid enough.” In the analysis of the qualitative data collected in response the a question regarding the barriers and challenges teachers faced in implementing the co-teaching model at Study school, the responses were both at the general level of co-teaching challenges as well as those challenges that appear to be unique to the co-teaching model at Study school. Barriers and challenges 35 PROGRAM EVALUATION participants identified that are reflective of the co-teaching literate at large were the need for more planning time, relationship difficulties, and clashes in teaching styles. One teacher said of her co-teaching challenges, “communication and expectations! I have had my own classroom for years and years….having to share is a change.” However, many of the challenges raised by the respondents are related to the unique coteaching model in place at Study school. As with the responses to benefits, those teachers working with a teaching assistant in the co-teaching role voiced frustration with the arrangement. For example, one teacher stated, “My situation is not co-teaching. …I think asking my assistant to do things that she has not been trained in or getting paid for is not equitable.” Another teacher in this situation said, “My assistant does not necessarily have the knowledge required to help the students with the content they are learning, so I find myself having to teach her as well.” Another unique challenged raised by the respondents comes from the general education teachers whose co-teachers are specialists (special education, English language learners and reading specialists) as well as from the specialists themselves. Most of these responses involve the issue of the specialists having to fill the role of co-teacher while still juggling and maintaining their role as a specialist for their entire caseload. One general education teacher said of the situation, “Hard to actually have the co-teaching experience when I feel like my co-teacher is so busy with ELL stuff….wish she could be focused solely on being a co-teacher.” One reading specialist said of her co-teaching experience, “I am in 3 different grade level classrooms with the expectation that I am to have equal responsibility for all the students in each room yet I am frequently out attending meetings. I do everything 3 times. I need to be very knowledgeable in 3 different grade level SOL’s.” 36 PROGRAM EVALUATION The number of co-teaching partnerships was also brought up repeatedly as a barrier to coteaching. One general education teacher who works with two co-teachers said, “Because each teacher is only in my classroom for half the day and I am with the students all day, I feel as though it is still a ‘my class’ mentality and not quite yet an ‘our class’ one. I still do report cards, conferences, and grading the majority of the time.” The responses about the amount and type of professional development training (PD) were fairly equally divided between those people who thought the training received was good but that more was needed and those people who felt that the training was not helpful and those who thought some aspects were good while others were lacking. Overall 38% of respondents felt that the PD was adequate. Another 31% of respondents felt that the PD was not helpful while another 31% of respondents felt that some aspects of the training was good but that it was inadequate or poorly timed. Those respondents who felt that the professional development was inadequate cited experience as the best method of preparation or they cited that the professional development did not address the unique co-teaching model being implemented at Study school. One teacher said, “I feel that the PD gave what administration wanted it to look like; however it is not actually run like that. If this was a perfect world and we all had co-teachers, then I think there may be a chance o fit working.” Summary. The results of the analysis indicate Study school is not implementing the best practices in the co-teaching program as intended by having co-teaching teams plan together, teach together, and assess together. The results also indicate teaching assistants are not perceived to be qualified to assume the role of a co-teacher. The average response of all respondents suggest the best practices of the Stetson co-teaching model are being implemented, but detailed analysis of the data by the type of co-teaching partnership and triangulation from the analysis of 37 PROGRAM EVALUATION the quantitative data on the roles and responsibilities of collaborative teachers, analysis of the pre-existing schedules, and qualitative responses indicate inequity occurs in all types of coteaching partnerships, particularly in collaborative planning and assessment . In co-teaching partnerships consisting of one general education teacher and one specials teacher, specials teachers are serving dual roles as a fully functioning co-teacher and a specials teacher. Special teachers are either pulled from classrooms resulting in inequity in planning and instruction time or being stretched to fulfill the responsibilities of being both a specials teacher and a co-teacher. In co-teaching partnerships consisting of multiple partnerships inequity occurs in the amount of planning time, instructional time, and development and administration of assessments. Although co-planning time is currently built into the weekly schedules of all teachers, those who work with more than one co-teacher have less time with each, and coplanning times are inconsistent. The existing data from the schedules indicates classrooms with two co-teaching partnerships lose an average of 0.92 hours of co-instructional time each week and classrooms with three co-teaching relationships lose an average of 2.5 hours of coinstructional time each week as opposed to classrooms with one co-teaching partnerships which only lose an average of 0.09 hours of instructional time each week due to scheduling conflicts. There are not enough teaching assistants, special education teachers, ELL teachers and reading specialists to provide every general education teacher with a full-time co-teacher. In co-teaching partnerships consisting of one general education teacher and one teaching assistant inequity occurs in the practice of collaborative planning, instruction, assessment implementation, and in the roles and responsibilities of the partners. The quantitative data indicates collaborative planning between the partners occurs infrequently or not at all. From the 38 PROGRAM EVALUATION general education teachers’ perspective, the amount of support and expertise in the classrooms may not be equitable, and the teaching assistants may feel that they are being asked to work outside of their job descriptions. This is evidenced by general education teachers’ responses in feeling teaching assistants do not have the knowledge or experience in assuming the role of a classroom teacher. The lack of responses to the questionnaire by teaching assistants indicates teaching assistants might not consider themselves an equal partner as well. One teaching assistant reported he/she didn’t think the mass mailing asking members of co-teaching teams to complete the questionnaire concerned teaching assistants so the request was ignored. The Roles and Responsibilities of Collaborative Teachers: A Decision Making Exercise document clearly states the partnership consists of two certified teachers. Student outcomes may be impacted by the allocation of resources. There is no evidence to suggest the needs of all students are being met. Some students have no contact with the experts who have historically provided support and remediation services. One general education teacher indicated, “Our class got filled with challenging students and it is overwhelming for both teachers. It is too much for even 2 teachers. The co-teacher does not know the curriculum, grading system or resources used.” Limitations. More in-depth interviews, another iteration of the questionnaire, and better communication with teachers and teaching assistants at the Study school would add validity to the results of this evaluation. More in-depth interviews with administrators would have provided a better understanding of the scheduling and staffing decisions made in implementing the coteaching program. There was no evidence to support whether the needs of all students were being met by placement of the specials teachers in the role of a co-teacher. 39 PROGRAM EVALUATION Another iteration of the questionnaire would have addressed more of the roles and responsibilities of the co-teachers in the partnership including the following: questions concerning the preparation of materials; development of individual behavior plans; tracking and updating of IEPs; communication with parents; and duties performed outside of school hour. Questions addressing the best practices in ancillary outlined in the Assessment of Collaborative Teaching Practices in an Inclusive Classroom document were overlooked in preparing the questionnaire. Better communication with teaching assistants would have provided a more representative sample of the teaching assistants’ perceptions of how the best practices of coteaching are being implemented and how the roles and responsibilities of a co-teacher are being filled. However this lack of communication provided insight into how teaching assistants view their role in the co-teaching partnership. One teaching assistant indicated she felt the request to fill out the questionnaire did not apply to her because she received it as a mass email and assumed it only applied to teachers which is the usual intent. Recommendations The following recommendations are suggested as a result of this study. The scheduling of multiple partnerships should be re-evaluated to ensure equity in collaborative planning and instructional time and ensure the needs to all students are being met. Teaching assistants should not be expected to assume the role of a co-teacher. They do not have the qualifications or the experience to assume the responsibilities. Additional professional development will not provide this expertise. If the general education teachers and teaching assistants are more comfortable in their traditional roles it is suggested they continue with this form of partnership until funds are provided to staff each classroom with two certified teachers. 40 PROGRAM EVALUATION References Austin, V. L. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs about co-teaching. Remedial & Special Education, 22, 245-256. Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children. 28 (3), 1 – 16. Faltis, C. J. (2001). Joinfostering: Teaching and learning in multilingual classrooms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- Grant, C. A., (1999). Multicultural Hall. Ferguson, R. F. (2007). Toward excellence with equity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Friend, M., Cook, L., Hurley-Chamberlain, D., & Shamberger, C. (2010). Co-teaching: An illustration of the complexity of collaboration in special education. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20, 9-27. Guilford. (2013). Guilford Elementary School Website. Retrieved from http://www.lcps.org/guilford Hepner, S., & Newman, S. (2010). Teaching is teamwork: Preparing for, planning, and implementing effective co-teaching practice. International Schools Journal. 29, 67-81. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 612 (a) (5) et seq. Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/,root,statute,I,B,612,a,5 Keefe, E. B., & Moore, V. (2004) The challenge of co-teaching in inclusive classrooms at the high school level: What the teachers told us. American Secondary Education, 32 (3), 7788. Keefe, E. B., Moore, V., & Duff, F., (2004). The four “knows” of collaborative teaching. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36 (5), 36-42. 41 PROGRAM EVALUATION Loudoun County School Board. (2011). Annual Report of the Special Education Committee to the Loudoun County School Board (October 11, 2011). Retrieved from http://www.lcps.org/cms/lib4/VA01000195/Centricity/Domain/103/presentations/SEAC_ ANNUAL_REPORT_2010-20111013.pdf Mastropieri, M. A., Scruggs, T. E., Graetz, J., Norland, J., Gardizi, W., & McDuffie, K. (2005). Case studies in co-teaching in content areas: Successes, failures, and challenges. Intervention in School and Clinic, 40, 260-270. McGraner, K. L., Saenz, L. (2013) Preparing teachers of English language learners. TQ Connection Issue Paper. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality, Department of Education. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov.mutex.gmu.edu/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED5 43816 Murawski, W. W., & Swanson, H. L. (2001). A meta-analysis of co-teaching research: Where are the data? Remedial and Special Education, 22, 258-267. NEA Today (2008). Challenges. 27 (1), 39. Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & McDuffie, K. A. (2007). Co-teaching in inclusive classrooms: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Exceptional Children, 73, 392-416. Stetson (2013a). Stetson and Associates, Inc. website – www.stetsonassociates.com. This website provides background information, resources, training materials and evaluation tools. Stetson (2013b). Collaborative teaching: From separate to sensational. Stetson & Associates, Inc. https://secure.lcisd.org/lamarnet/SpecialEducation/images/Stetson%20Collaborative%20 42 PROGRAM EVALUATION Teaching%20Handouts-%20Staff%20Development.pdf. This document describes the Stetson model. Stetson Online Learning (2013). Stetson Online Learning Website. Retrieved from www.stetsonoline.net. This website provides information on Stetson’s training program and online leaning. Stetson Training (2013). Stetson Cooperative Teaching Training Tools and Forms. http://goo.gl/aiCxc. This is a collection of training tools and evaluation forms that are used in training sessions. Study School (2013). Professional Development PowerPoint Presentation. Study School Staff Drive. This was a presentation to the Study School staff that provides information on what co-teaching is and how Study School plans to implement it. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2012). Digest of Education Statistics, 2011 (NCES 2012-001), Table 47. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=59. Walther-Thomas, C. S., (1997). Co-teaching experiences: The benefits and problems that teachers and principals report over time. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30, 395-407. Walther-Thomas, C., (1996). Planning for effective co-teaching: The key to successful instruction. Remedial and Special Education, 17, 255 – 264. Friend, Weiss, M. P., & Ainsworth, M. K. (2013). Co-teaching: Addressing fidelity of implementation. Manuscript submitted for publication. 43 PROGRAM EVALUATION Appendix A Logic Model Study Elementary School Co-Teaching Program Situation: Study School is a Title I school in Loudoun County Virginia, currently designated a Focus School, because it failed to meet Annual Measureable Objectives (AMOs). Priority: To maximize instructional time and the use of human resources to improve student scores on state tests and overall school performance. Inputs Activities teachers professional development teaching assistants reallocate staff, administrators develop schedules time plan together training additional county money implement together assess together Assumptions: Co-teaching improves learning. Outputs Participation teachers teaching assistants students administrators parents Short Increased instructional time Student access to a wider range of instructional strategies and expertise. External Factors: Student demographics. Outcomes Medium Long Increased student learning. Higher student scores on state tests. Improved school performance so that school is no longer a focus school. 44 PROGRAM EVALUATION Appendix B Co-Teaching Questionnaire 45 PROGRAM EVALUATION 46 PROGRAM EVALUATION 47 PROGRAM EVALUATION 48 PROGRAM EVALUATION 49 PROGRAM EVALUATION 50 PROGRAM EVALUATION 51 PROGRAM EVALUATION 52 PROGRAM EVALUATION 53 PROGRAM EVALUATION 54 PROGRAM EVALUATION Appendix C Scheduled and Actual Co-planning and Co-Instructional Hours per Week Classroom K1 K2 K3 K4 2A 2B 3B 5A 5B 5C 5D 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E 2C 2D 3A 3C 3D 4B 4D 2E 4A 4C Average No. of coteachers 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 Scheduled planning hours 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 5 2 5 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 2.35 Planning hours lost 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.31 Total planning hours 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.5 4 4 4 4 4 2 4 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 2.08 Scheduled CoTotal coinstructional instructional. instructional hours hours lost hours 27.5 0 27.5 27.5 0 27.5 27.5 0 27.5 27.5 0 27.5 22.5 0 22.5 23.75 0 22.5 23.75 0 23.75 20 0 20 21.25 0 21.25 21.25 0 21.25 20 1 19 22.5 1 21.5 20 1 19 20 0.5 19.5 22.5 0 22.5 22.5 0 22.5 15 0.5 14.5 20 3.5 16.5 22.5 1 21.5 21.25 0.5 20.75 22.5 1 21.5 13.75 1 12.75 15 1 14 17.5 2 15.5 21.25 2.5 18.75 16.25 3 13.25 21.35 0.75 20.55 55 PROGRAM EVALUATION Appendix D Frequency Data and Graphs from Google Survey Instrument 29 Responses 56 PROGRAM EVALUATION 57 PROGRAM EVALUATION 58 PROGRAM EVALUATION 59 PROGRAM EVALUATION 60 PROGRAM EVALUATION 61 PROGRAM EVALUATION 62 PROGRAM EVALUATION 63 PROGRAM EVALUATION Appendix E Frequency Data by Roles and Responsibilities 64 PROGRAM EVALUATION