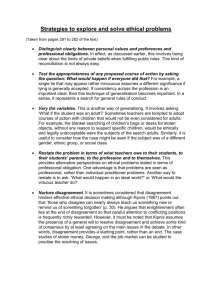

Philosophical Disagreement

advertisement

Philosophical Disagreement: You Should Think Either You are Full of Yourself, or You are Probably Wrong Mark Walker mwalker@nmsu.edu 1. Introductory Much of the literature on disagreement focuses on the issue of whether I am still entitled to believe that P, when I find out an epistemic peer believes not-P.1 Given some plausible assumptions, including fallibilism and disagreement about contrary rather than contradictory philosophical positions, if evidence of disagreement carries epistemic weight for you, then, for many philosophical views, you should believe that your preferred philosophical position is probably false. If you do not think your position is probably false, then disagreement with epistemic peers carries very little epistemic weight for you, which is a polite way to say you must be full of yourself. 2. A Few Distinctions and a Simple Example Jennifer Lackey, I believe, fairly describes how ‘epistemic peer’ is often used in the literature: A and B are epistemic peers relative to the question whether p when A and B are evidential and cognitive equals with respect to this question—that is, A and B are equally familiar with the evidence and arguments that bear on the question whether p, and they are equally competent, intelligent, and fair-minded in their assessment of the evidence and arguments that are relevant to this question.2 A typical case involving epistemic peers is as follows: Two for Dinner: Suppose you and I go for dinner on a regular basis. We always split the check equally not worrying about whose dinner cost more, who drank more wine, etc. We also always add a tip of 23% and round up to the nearest dollar when dividing the check. (We reason that 1 One of the few exceptions is Bryan Frances who writes about epistemic superiors. (Bryan Frances, Philosophical Renegades (Oxford University Press Oxford, 2013). 2 Jennifer Lackey, ‘Disagreement and Belief Dependence: Why Numbers Matter’, in The Epistemology of Disagreement: New Essays, 2013, pp. 243–68. 243. In a similar vein, Christensen writes: “Much of the recent discussion has centered on the special case in which one forms some opinion on P, then discovers that another person has formed an opposite opinion, where one has good reason to believe that the other person is one’s (at least approximate) equal in terms of exposure to the evidence, intelligence, freedom from bias, etc.” (David Christensen, ‘Disagreement as Evidence: The Epistemology of Controversy’, Philosophy Compass, 4 (2009), 756–67.) Notice that Christensen writes “approximate equal”. In a footnote (243, note 2) Lackey qualifies her definition to say “roughly equal”. This sort of qualification to ‘epistemic peers’ (approximately, or roughly) will be assumed throughout this paper. 1 20% is not enough and 25% is ostentatious). We both pride ourselves on being able to do simple arithmetic in our heads. Over the last five years we have gone out for dinner approximately 100 times, and twice in that time we disagreed about the amount we owe. One time I made an error in my calculations, the other time you made an error in your calculations. Both times we settled the dispute by taking out a calculator. On this occasion, I do the arithmetic in my head and come up with $43 each; you do the arithmetic in your head and come up with $45 each. Neither of us has had more wine or coffee; neither is more tired or otherwise distracted. How confident should I be that the tab really is $43 and how confident should you be that the tab really is $45 in light of this disagreement?3 It will help to have a bit of machinery to explain what is puzzling about such cases. Sometimes disagreement is modeled in terms of belief/disbelief and withholding of belief4, but for our purposes, following Kelley, it will help to borrow the Bayesian convention where numbers between 1 and 0 are used to indicate credence about some proposition.5 1.0 indicates maximal confidence that the proposition is true, 0.0 maximal confidence that the proposition is false, and 0.5 where one does not give more credence to the proposition being true than to credence of the proposition being false. Briefly, the puzzle about such cases is this: if we are epistemic peers, then it seems that I should think we are equally reliable in ascertaining whether P. (And if I don’t think we are equally reliable, then it is hard to see in what sense we are epistemic peers.) So, if I think that I am highly reliable (say greater than 0.95) in ascertaining whether P, then you too must be highly reliable (greater than 0.95) in ascertaining whether P. But if you believe not-P, and I believe that P, then we cannot both be right. This means that the initial estimation of individual reliability must be wrong (at least one of us must be less reliable in this instance than the initial estimate suggests). It is common to distinguish between ‘conciliatory’ and ‘steadfast’ ends of a spectrum of revision in confidence in light of disagreement. At the former end …are views on which the disagreement of others should typically cause one to be much less confident in one’s belief than one would be otherwise – at least when those others seem just as This is basically David Christensen’s example with minor tweaking. See David Christensen, ‘Epistemology of Disagreement: The Good News’, The Philosophical Review, 2007, 187–217. Christensen, ‘Disagreement as Evidence’. 4 Richard Feldman, ‘Respecting the Evidence’, Philosophical Perspectives, 19 (2005), 95–119. 3 5 Thomas Kelly, ‘Peer Disagreement and Higher Order Evidence’, in Disagreement. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2 intelligent, well-informed, honest, free from bias, etc. as oneself.…. At the latter end are views on which one may typically, or at least not infrequently, maintain one’s confidence in the face of others who believe otherwise, even if those others seem one’s equals in terms of the sorts of qualifications listed above.6 The most extreme version of conciliation is what has been termed “splitting the difference” or “equal weight” view.7 Applied to the Two for Dinner case, it requires assigning equal credence to the claim that the tab is $43 each and the claim that the tab is $45 each. The most extreme version of steadfast permits my credence to remain unchanged, even in light of your excellent track record. Since this is a continuum, there are any number of intermediate positions. For example, one possibility is that credence should only be reduced by half the difference suggested by the equal weight view. To keep the arithmetic simple, let us suppose that initially I am supremely confident that the tab is $43 (credence = 1.0). I then find out you think the correct number is $45. The equal weight view recommends I hold with 0.5 credence the claim that the tab is $43 and give 0.5 credence to the claim that it is $45. A moderate position, which recommends half that of the equal weight view, gives a split of 0.75 to the claim that it is $43 and 0.25 to the claim that it is $45. Conciliation and steadfast indicate how much change in credence (if any) there should be in light of evidence of disagreement. We can also classify different levels of credence in some proposition P as follows. Let us understand ‘dogmatism’ as the view that subject S has a credence of greater than 0.5 concerning some proposition P. So, suppose you believe there is a 60% chance of rain tomorrow. You might say, “It will probably rain tomorrow” and this would count as dogmatism in our sense. ‘Skepticism’ is the view that some subject S has a credence is 0.5 whether some proposition P. This sense of ‘skepticism’ follows the recommendation of Sextus Empiricus: The Skeptic Way is a disposition to oppose phenomena and noumena to one another in any way whatever, the result that, owing to the equipollence among the things and the statements thus opposed, we are Christensen, ‘Disagreement as Evidence’. There are several versions of ‘Steadfast’ in the literature, some of which include as part of the definition what we will describe as a dogmatic attitude (see below), for example, Kenneth Boyce and Allan Hazlett, ‘Multi-Peer Disagreement and the Preface Paradox’, Ratio, 2014. 7 The Term ‘equal weight’ comes from Adam Elga, ‘Reflection and Disagreement’, Noûs, 41 (2007), 478–502. Obviously, more extreme revision is possible. We might think of ‘capitulation’ denoting cases where I revise my confidence to match yours, e.g., I become as certain as you are that the total is $45. This view might make sense when one is dealing with an epistemic superior, but seems unmotivated in the case of epistemic peers. The equal weight version of conciliation, then, is the mean between total capitulation and complete steadfast. 6 3 brought first to epochè and then to ataraxia. … By “equipollence” we mean equality as regards credibility and the lack of it, that is, that no one of the inconsistent statements takes precedence over any other as being more credible. Epochè is a state of the intellect on account of which we neither deny nor affirm anything.8 If you think that the evidence does not favor the view that it will rain tomorrow, and you do not think the evidence favors the view it will not rain tomorrow, then you are a skeptic about the claim “It will rain tomorrow”. You neither affirm nor deny the claim. Finally, ‘skeptical dogmatism’ is the view that a subject S has a credence of less than 0.5 concerning some proposition P. Skeptical dogmatism about “It will rain” translates into something like denying “It will rain” or holding “It probably won’t rain”. As the quote above indicates, Sextus Empiricus would not approve of denial any more than affirming some proposition. It should be clear that the conciliation/steadfast distinction is independent of the dogmatism/skepticism/ skeptical dogmatism distinction: Suppose I am skeptical about some proposition P (credence = 0.5), and you are a dogmatist about P (credence = 0.7), and I believe conciliation applies in this instance, then I should become a dogmatist about P (credence = 0.6). If I believe in steadfast, then I should remain a skeptic. As is often observed, almost everyone thinks that steadfast is appropriate under some circumstances and conciliation is appropriate in others.9 The real source of controversy is under which circumstances each is appropriate. Accordingly, let us think of ‘epistemic humility’ as the degree of the disposition to revise one’s confidence in light of countervailing evidence, including epistemic disagreement; whereas, ‘epistemic egoism’ is the degree of the disposition to retain one’s confidence in light of countervailing evidence, including evidence from disagreement.10 So, ‘conciliation’ and ‘steadfast’ indicate the degree of revision (from no revision to equal weight), while ‘epistemic humility’ and ‘epistemic egoism’ indicate the degree of resistance to change. To illustrate, in the Two for Dinner example, if I remain steadfast, then I have a higher degree of epistemic egoism as compared to if I revise my credence downwards in accordance with the equal weight view. Alternatively, we might say that when I revise my confidence down I exhibit greater epistemic humility than in the case where I remain steadfast. Suppose the Two for Dinner example is changed such that you have a terrible track record for 8 Benson Mates, The Skeptic Way (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). P. 8-10. Alex Worsnip, ‘Disagreement about Disagreement? What Disagreement about Disagreement?’, Philosopher’s Imprint, 2014, 1–20. 10 It would perhaps be more accurate to say “putative counter evidence’ since the defeating evidence might be thought defeated by the epistemic egoist. If you are strongly attracted to epistemic egoism, then you might read ‘evidence’ as “putative evidence”. Your homework will be to show that the putative evidence is not, in fact, evidence. 9 4 getting the total right: you are right only 50% of the time. In this case, I may remain steadfast while demonstrating little epistemic egoism. Since you are an “epistemic inferior”, the countervailing evidence against my belief that the tab is $43 is much less in this instance. The example might be changed in the other direction: while I am in the restaurant bathroom you take a picture and post our restaurant check on Facebook. Fifty of your charter accountant Facebook friends just happen to be online. With calculators in hand, they post that they agree with you that the correct number is $45. If I remain steadfast under these conditions, I exhibit a high degree of epistemic egoism, since my belief faces the defeater of so many epistemic superiors saying otherwise. 3. Probably Wrong in The Two Person Case In the next few sections, I want to assume the extreme version of conciliation, the equal weight view, and see where it takes us. A common thought, and one sometimes used to defend steadfast, is that conciliation inevitably leads to skepticism. As Christensen points out: The most obvious motivation for Steadfast views on disagreement flows from the degree of skepticism that Conciliationism would seem to entail. There must be something wrong, the thought goes, with a view that would counsel such widespread withholding of belief. If you have an opinion on, for example, compatibilism about free will, scientific realism, or contextualism about knowledge, you must be aware that there are very intelligent and well-informed people on the other side. Yet many are quite averse to thinking that they should be agnostic about all such matters. The aversion may be even stronger when we focus on our opinions about politics, economics, or religion.11 Christensen is probably right that most see skepticism, “withholding of belief”, to be a consequence of conciliation. For example, in a seminal article on peer disagreement, Richard Feldman writes: That is, consider those cases in which the reasonable thing to think is that another person, every bit as sensible, serious, and careful as oneself, has reviewed the same information as oneself and has come to a contrary conclusion to one’s own. And, further, one finds oneself puzzled about how that person 11 Christensen, ‘Disagreement as Evidence’. 757-758 5 could come to that conclusion…..These are cases in which one is tempted to say that ‘reasonable people can disagree’ about the matter under discussion. In those cases, I think, the skeptical conclusion is the reasonable one: it is not the case that both points of view are reasonable, and it is not the case that one’s own point of view is somehow privileged. Rather, suspension of judgment is called for.12 However, this is the wrong conclusion to draw, at least given a modicum of fallibilism. The correct conclusion is skeptical dogmatism. To see why, think again about Two for Dinner. The skeptical position is that belief that the tab is $43 has a 0.5 credence. Notice, however, that the propositions that the tab is $43 and the tab is $45 are not contradictories but contraries: both cannot be true, but both can be false. If we allow a modicum of fallibilism about the probability that both estimates are wrong, then I should put some small credence in the proposition that we both got the calculation wrong. Even if the credence that we might have both got it wrong is miniscule, and we apply the equal weight view, then credence I should put into my original estimate that the tab is $43 per person must be less than 0.5. To illustrate: let us suppose that I have a credence of 0.001 that both propositions are false. The maximum credence I can have that $43 is correct, given the equal weight view, is 0.4995. Or to put the point in a slightly different manner, if I give equal weight to our two views, and allow a modicum of fallibilism to the effect that we might both be wrong, then it is more likely that I am wrong and either you are right, or we are both wrong. The same line of reasoning shows what is wrong with the usual way of modeling disagreement, which we will refer to as the ‘binary contradictories model’ (or simply the ‘binary model’ for short). The binary model says disagreement is best modeled as one party asserts ‘P’ and the other party asserts ‘not-P’.13 On the face of it, this looks plausible enough. Suppose we model the Two for Dinner example in this way. I claim: P = Our share of dinner is $43. You claim Not-P = It is not the case that the tab is $43. However, this is implausible. Imagine then we take out our calculators and both agree with the added help that the total is actually $44. You say: “See, I was right: the tab is not $43.” Your joke turns on conflating Richard Feldman, ‘Epistemological Puzzles about Disagreement’, in Epistemology futures, 2006, pp. 216–36. 235 I will add use/mention punctuation only where I think it helps. 12 13 6 contradictories and contraries. It would be better to model the disagreement as ‘contraries disagreement’. I assert P, you assert: Q = Our share of dinner is $45. We allow some small credence to: R = Our share of dinner is neither $43 nor $45. Modeling the disagreement as a binary disagreement, as opposed to a contraries disagreement, makes it much harder to appreciate the possibility of mutual error or what we will refer to as ‘contraries fallibilism’. Yes, it is true that Q implies not-P, but ‘Q’ and ‘not-P’ are not identical. Leaving out the fact that your reason for asserting not-P is Q fails to correctly model those situations where not-P is true and Q is false (e.g., when the tab is $44). 4. Probably Wrong in Multi-Proposition Disagreements Let us think of ‘multi-proposition disagreements’ as disagreements where there are three or more contrary positions at issue among three or more disputants.14 Multi-proposition disagreements can be represented as disagreements amongst at least three disputants about contraries P, Q, R...15 To illustrate, consider a three person analog of our previous example: Three for Dinner: Suppose you and I go for dinner with Steve on a regular basis. We always split the check equally not worrying about whose dinner cost more, who drank more wine, etc. We also always add a tip of 23% and round up to the nearest dollar when dividing the check. (We reason that 20% is not enough and 25% is ostentatious). The three of us pride ourselves on being able to do simple arithmetic in our heads. Over the last five years we have gone out for dinner approximately 100 times, and three of those times we disagreed about the amount each of us should pay. One time I made an error in my calculations, the other time you made an error in your calculations and the third time it was Steve. In each case, we settled the dispute by taking 14 Boyce and Hazlett layout out some of the usual conceptual terrain here: One problem in the epistemology of disagreement (Kelly 2005, Feldman 2006, Christensen 2007) concerns peer disagreement, and the reasonable response to a situation in which you believe p and disagree with an “epistemic peer” of yours (more on which notion in a moment), who believes ~p. Another (Elga 2007, pp. 486-8, Kelly 2010, pp. 160-7) concerns serial peer disagreement, and the reasonable response to a situation in which you believe p1 … pn and disagree with an “epistemic peer” of yours, who believes ~p1 … ~pn. A third, which has been articulated by Peter van Inwagen (2010, pp. 27-8) concerns multi-peer disagreement, and inquires about the reasonable response to a situation in which you believe p1 … pn and disagree with a group of “epistemic peers” of yours, who believe ~p1 … ~pn, respectively. (Boyce and Hazlett.) Multi-proposition disagreement is related to, but different from, the three issues that Boyce and Hazlett delineate. 15 Of course I am also assuming that each contrary has at least one epistemic peer proponent. 7 out a calculator. On this occasion, I do the arithmetic in my head and come up with $43 each; you do the arithmetic in your head and you come up with $45 each, while Steve comes up with $46 each. The three of us had the same amount of wine and coffee, and none of us are more tired or otherwise distracted than the others. How confident should I be that the tab really is $43, how confident should you be that the tab really is $45, and how confident should Steve be that the tab really is $46 in light of this disagreement? Applying the equal weight view, we get the result that the maximum credence I should have that $43 is the correct amount is 0.3333. Here my reasoning might be that I have good track record evidence that we are equally reliable in terms of getting the right total, and since at most one of us is correct, I should put no more than 0.3333 credence in the claim that I am right and you two are wrong. The same point would apply to your total and Steve’s. As in Two for Dinner, the claims that the tab is $43, $44 or $45 are contraries: only one can be correct, but all three could be false. Of course, we might allow that the credence that all three of us made an error is less than it is in the two person case, perhaps as little as 0.0001. In any event, both contraries fallibilism and multiproposition disagreements lead to skeptical dogmatism on their own (when combined with equal weight), so it should be no surprise that together they add up to an even stronger claim for skeptical dogmatism. In this case, my credence for the belief that the tab is $43 should be less than 0.3333. 5. Many Philosophical Disputes Are About Contraries Are philosophical disagreements better modeled as binary or multi-proposition disagreements? It is certainly true that philosophical debates are often cast in terms that seem to suggest the binary model. However, the question is whether such debates are best characterized as philosopher X arguing for P and philosopher Y arguing for not-P. For example, imagine Daniel Dennett and Alvin Plantinga are invited to debate theism by some university organization who has agreed to pay tens of thousands of dollars each for their performance. The poster for the event reads: “Does God exist? Professors Alvin Plantinga and Daniel Dennett take opposing sides. The event promises to be a spectacular philosophical bloodbath of epic proportions: Two men enter, one man leaves.” We may think of the debate proposition as P = We are justified in believing God exists. 8 It is true that Dennett will argue against P, and so gives the appearance of the debate having the form of the binary model. However, it is more accurate to say that Dennett will argue for a proposition that implies the falsity of P. In particular, at least part of Dennett’s brief will be: Q: We are justified in believing atheism. Q, we will assume, implies not-P. But the fact that Q implies not-P clearly does not show that ‘Q’ and ‘not-P’ are equivalent. This is confirmed when we realize that we can imagine at least two other debating partners for Plantinga. Plantinga might be invited on another occasion to India to debate a Hindu philosopher who believes we are justified in believing polytheism: R: We are justified in believing in multiple gods. R, we will assume, implies not-P. (P is committed to the existence of one true God, the polytheism of R is committed to a multiplicity of divine beings.) Finally, we might imagine an agnostic debating Plantinga; someone who believes that we do not have justified belief in God, nor do we have justified belief in the nonexistence of God: S: We are not justified in believing or disbelieving in the existence of any divinities. S, we shall assume, implies not-P as well. So, although these three positions imply not-P, the positions themselves are clearly different from not-P, which lends support to the idea that the disagreement is best modeled as a multi-proposition disagreement. The fact that the binary model is inadequate to model the disagreement between Dennett and Plantinga is further confirmed when we imagine the day of the debate unfolding as follows. Dennett makes opening remarks in favor of atheism, Plantinga responds arguing for theism using the ontological argument. Just as the debate is about to be opened up to questions from the audience, a flash of lightning temporarily blinds everyone in the auditorium and Zeus, Poseidon and Hades appear on stage. They put on a display of their powers sufficient to convince all present that they are the real deal. Plantinga then remarks that he wins the debate because Dennett is wrong: there is a divine presence. Dennett remarks that Plantinga is wrong because his Christian god does not exist (and Zeus, Poseidon and Hades agree with Dennett on this point). The moderator of the debate declares both men wrong. The point here is rather banal: major disagreements in the philosophy of religion tend to focus on disputes that are contraries, not contradictories: the truth of one implies the falsity of the rest, but not vice versa. This is hardly news for anyone who has taught these debates: part of the pedagogical work is to help students 9 see the logical relationships between the various positions. Appealing to the binary model is an invitation to forget this important point. In the political realm, it might be tempting to think of the great debate between Rawls16 and Nozick17 in terms of a binary model, yet the multi proposition disagreement model is more apt. Consider Goodin’s utilitarianism as public philosophy18, and Cohen’s socialism19 are competitors to Rawls’ justice as fairness and Nozick’s libertarianism. Some other debates that have the structure of multiple-proposition disagreements include: Ontology: materialism vs. immaterialism vs. dualism Ethics: virtue ethics vs. consequentialism vs. deontology Free Will: compatibilism vs. determinism vs. libertarianism Philosophy of Science: realism vs. empirical realism vs. anti-realism vs. constructivism It may be that there are some, perhaps many, binary disagreements in philosophy, e.g., abortion is permissible/not permissible, capital punishment is permissible/not permissible, and compatibilism/incompatibilism.20 We can rest content here with the more limited claim that many important philosophical disputes are multi-proposition debates. If the equal weight view is applied to multiple-proposition philosophical disagreements, then we should conclude that proponents of each view are probably wrong. For example, let us imagine Rawls endorses the equal weight view. He disagrees with Nozick, Goodin and Cohen, but he regards them as epistemic peers. So, he should reason that his justice as fairness view has at most a 0.25 probability of being correct, given that each of his peers is just as likely to be correct. Moreover, if he is a fallibilist and allows that all four views might be false, he should reason that the probability that justice as fairness view is correct is less than 0.25. But, couldn’t Rawls take a page from President George Bush and simply define the disagreement in binary terms? He might say either you are for justice or fairness (J) or you are against it (not-J). There are at least three problems with this maneuver. 16 J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1971). R. Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia (Basic Books, 1974). 18 Robert E. Goodin, Utilitarianism as a Public Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1995). 19 Gerald Allan Cohen, Why Not Socialism? (Princeton University Press, 2009). 20 Even these examples are not clear cut. The permissible/impressible abortion question can be parsed further: permissible in the first trimester, second trimester, and third trimester, for example. Also, cases where the mother’s life is at risk, the pregnancy is the result of rape, or where the fate of the universe hangs in the balance, may divide proponents on both sides of the permissible/impermissible opposition. 17 10 First, as already indicated, the model doesn’t capture all there is to the actual disagreement. For example, the proposal lumps Cohen, Nozick and Goodin as proponents of not-J, but this leaves unexplained all the disagreement amongst proponents of not-J. It is not hard to imagine that Nozick finds Cohen’s socialism more anathema than Rawls’ justice as fairness. So, the binary model doesn’t explain why those on the “not-J team” squabble so much amongst themselves. The multi-proposition model has a straightforward explanation: Cohen, Nozick and Goodin claim not-J as an implication of their preferred philosophical theories. The binary model papers over the differences amongst Cohen, Nozick and Goodin. Second, there does not seem to be a principled answer to the question: Which binary model should be adopted? Nozick, it seems, could just as easily invoke Bush and say either you are for libertarianism (L) or you are against it (not-L). Cohen and Goodin could say similar things (mutatis mutandis) as well for socialism (S) and utilitarianism (U). If only one binary model is correct, then how can we say, in a principled way, which one? If all the binary models are correct, then it is not clear that there is going to be any purchase over the multiple-proposition disagreement model. After all, if we use the set of binary models, it will turn out that at most one of (J), (L), (S) and (U) is true, but more than one of (not-J), (not-L), (not-S) and (not-U) may be true, which is just to say they are contraries. Modeling the disagreement as sets of binary disagreements complicates without adding anything of value. Third, even if it could somehow be maintained that the best way to model disagreement about distributive justice is (J) versus (not-J), this would help Rawls only to the extent that he believes that the number of epistemic peers do not matter.21 In the example we are working, on the multi-proposition model, there are four positions with one proponent each. On the binary disagreement there is a 3 to 1 ratio in favor of (not-J) over (J). The general principle is perhaps obvious: the more one defines one’s position as the center of any disagreement, the more one lines up one’s opponents specifically in opposition. 21 As Jennifer Lackey points out, many do think that numbers matter. If we change the Three for Dinner example such that both you and Steve believe the tab is $45, this seems to provide even greater evidence that I am wrong than in the Two for Dinner version. Usually the thought that numbers matter is supplemented with the idea that there is epistemic independence. If masses of libertarians are produced by brainwashing at the Nozick summer camp for kids, graduates from the camp won’t add weight to the libertarian cause. See Lackey for thoughtful discussion on how to spell out what ‘independence’ might mean here. (Lackey, ‘Disagreement and Belief Dependence’.) Here I ignore the question of numbers as it involves all sorts of hard work. We would need to somehow operationalize ‘epistemic peer’ for philosophical positions and then go out and do some head counting. We would then have to figure out how to add up the epistemic weight of differing numbers. In theory, however, Rawls might remain a dogmatist about justice as fairness, even though it is a multi-proposition disagreement, so long as there are more on team justice as fairness than the other teams. 11 6. Resisting Skeptical Dogmatism: Epistemic Egoism and Epistemic Humility In this section, I will try to show two results: First, maintaining dogmatism in a multiple-proposition disagreement requires more epistemic egoism than in comparable binary proposition disagreements, and second, skeptical dogmatism, rather than skepticism, in multi-proposition disagreements is the more epistemically humble position. Surprisingly, little epistemic egoism is necessary to maintain a dogmatic position using the binary disagreement model. For example, suppose we use the binary model to understand the disagreement between Rawls and Nozick. Suppose Rawls is initially supremely confident (credence = 1.0) as A Theory of Justice is published that justice as fairness is correct. Rawls, a few years later, reads Nozick’s Anarchy, State and Utopian and revises his credence on the assumption that Nozick is an epistemic peer. For Rawls to remain dogmatic about justice as fairness, he must think that justice as fairness has a credence of greater than 0.5. Suppose Rawls puts only slightly more credence in justice as fairness is correct than incorrect, 0.51. Rawls holds with 0.49 credence the proposition that Nozick is correct that justice as fairness is wrong. If perfect epistemic humility requires the equal weight view amongst epistemic peers22, then Rawls in this case would be pretty close to the ideal of epistemic humility, even though he is still a dogmatist. Perfect humility would require skepticism on Rawls’ part, that is, for Rawls to neither deny nor affirm justice as fairness. Far greater epistemic egoism is required when modeling disagreements as multi-proposition disagreements as opposed to binary disagreements between two disputants, particularly so when factoring in fallibilism. For example, suppose Rawls allows a modicum of fallibilism about contemporary political philosophy; he allows that the correct theory may not have been articulated yet. So, we will assume a small number here, say 0.04 credence to the claim that utilitarianism, socialism, justice as fairness and libertarianism are false. This leaves 0.45 credence to share amongst the aforementioned colleagues, assuming Rawls remains a dogmatist with a credence of 0.51 that justice as fairness is correct. Imagine Rawls divides the remaining 0.45 credence evenly over the propositions that Nozick is correct, Cohen is correct and Goodin is correct. Rawls As Jennifer Lackey points out, “personal knowledge”, e.g., I might have better knowledge that I am tired than you, might make a difference as to how far we should apply the equal weight view. Jennifer Lackey, ‘What Should We Do When We Disagree?’, in Oxford Studies in Epistemology (Oxford University Press, 2008). If we accept this view about personal knowledge, then there may be times that perfect humility requires something other than splitting the difference. If I am feeling particularly mentally agile, I might give myself a slight edge, if I am feeling tired, then I might give you a slight edge. Notice throughout, including the Two for Dinner example, things that personal knowledge might favor or disfavor, such as being tired, are assumed not to be different between you and me. Factoring such personal knowledge cannot, by definition, make too much difference, otherwise the assumption about epistemic peers will have to be abandoned. There is little reason to suppose that Mark and JP are epistemic peers if Mark is always clear-head and wide awake while JP is almost always drunk and tired. 22 12 must think himself three times more likely to have arrived at the truth than each of his colleagues. Thus, other things being equal, greater epistemic egoism is required to maintain dogmatism in multi-proposition disagreements than in binary disagreements. Consider in the binary disagreement version, Rawls might say to Nozick as he passes him in the halls of Harvard: “Hi Bob, I’m slightly more likely to be right than you (0.51 versus 0.49 credence).” In the multiple-proposition variant, Rawls could not say such a thing. Rawls would have to say something more along the lines of: “Hi Bob, I’m more than three times likely to be right than you (0.51 versus 0.15 credence).” Or to put the point another way, it is one thing to say that you are more likely to be right than each of your colleagues on some issue, it is quite another to say that you are more likely to be right than all of your colleagues combined on the issue. Of course, this is just what Rawls would have to say to Nozick, Cohen and Goodin in our example: “Hi Bob, Gerald and Bob, I’m more likely to be right than the three of you put together.” Which is to say that to remain dogmatic in a multi-proposition philosophical disagreement requires a very robust form of epistemic egoism. Furthermore, moving from dogmatism to skepticism is not going to remove much of the sting of this much epistemic egoism. The reason, of course, is that we have already set the bar so low for dogmatism, specifically, requiring a credence of only 0.51. If Rawls were to become a skeptic about justice as fairness (credence = 0.5), then he would still have to say that he is about three times more likely to have arrived at the truth with justice as fairness than his three colleagues. Perfect epistemic humility in this instance would require the application of the equal weight view amongst the four epistemic peers, which would require that Rawls, Nozick, Cohen and Goodin all admit that they are probably wrong.23 Specifically, they might postulate, say, 0.04 credence to the claim that all four positions are wrong, and 0.24 credence to each of the four views. It will take a fair amount of epistemic egoism to move from 0.24 credence to either skepticism (0.5 credence) or dogmatism (0.51 credence). Conclusion So, in multi-propositional disagreements, if you are a dogmatist or a skeptic about some philosophical view, then you are further along the epistemic egoism end of the continuum than the comparable binary model suggests. If you are attracted to a degree of epistemic humility—you don’t think it is two or three times more It should be clear that there is the possibility of a third position in addition to epistemic egoism and epistemic humility. “Epistemic selfeffacement” is the tendency to give others epistemic credit. 23 13 likely that you have arrived at the correct philosophical view as compared with your philosophical colleagues— then you ought to think that you are probably wrong in endorsing any particular philosophical view in multiproposition disagreements. It is worth emphasizing that nothing here is an argument against dogmatism or epistemic egoism. Rather, the question going forward is whether the usual arguments currently deployed for maintaining dogmatism in light of evidence from disagreement are strong enough to withstand the greater evidential weight suggested by the multiple-proposition model. As noted, it is one thing to say that you are more likely to arrive at the correct view than each of your epistemic peers, it is quite another to say that you are more likely to arrive at the correct view than all of your epistemic peers in multi proposition disagreements. Naturally, it will be wondered which horn I would like to wear in putting forward this dilemma. I confess I am attracted to both. When I wave to my colleagues in my department down the hall, I often secretly think that I am right and they are all wrong about the various multi-proposition disagreements we have. In order to do so, I reject the assumption that they are epistemic peers. I think of them as my dim but well-meaning colleagues. When I greet them, I think things like “Hi dim JP” or “Hi dim Lori”, but, in an effort to keep a certain amount of collegiality in the department, I say “Hi JP” or “Hi Lori”. After all, as Aristotle points out, there is such a thing as excessive honesty. Dismissing them as epistemic peers is, of course, one way to manifest my disposition for epistemic egoism. But I am not ashamed of it. For too long, epistemic egoists have hid in the shadows. It is time we emerge from the closet and let the world know. Say it with me loud and proud, “I am an epistemic egoist. I am so brilliant that I am more likely to be right than all of my colleagues combined.” Other times, when I am not drinking, I confess that I think that any particular view that I put forward in multi-proposition debates is probably wrong. The debate over the epistemic import of disagreement itself seems a multi-proposition disagreement, hence, I must admit that the view advocated, either you should think you are probably wrong or full of yourself, is also probably wrong. But it will be asked: Why advocate a view, if it is probably wrong? The answer, in part, is that to advocate a view is not the same as believing a view. One might advocate a view that is probably wrong if it allows the view to be explored further. One might, following Mill, hope to get the view out there into the “market place of ideas” so that truth will eventually be winnowed from falsehood. After all, one can say that something is probably wrong but possibly correct—and it is not like any of the other views on this matter fare any better at this point. With just a little bit of epistemic egoism I might say that the view advocated here is probably wrong, but more likely to be right than any of its competitors. 14 Furthermore, there are any number of prosaic reasons for advocating a view without believing it: making a reputation for one’s self, filling in a line on one’s anal report, etc. References Boyce, Kenneth, and Allan Hazlett, ‘Multi-Peer Disagreement and the Preface Paradox’, Ratio, 2014 Christensen, David, ‘Disagreement as Evidence: The Epistemology of Controversy’, Philosophy Compass, 4 (2009), 756–67 ———, ‘Epistemology of Disagreement: The Good News’, The Philosophical Review, 2007, 187–217 Cohen, Gerald Allan, Why Not Socialism? (Princeton University Press, 2009) Elga, Adam, ‘Reflection and Disagreement’, Noûs, 41 (2007), 478–502 Feldman, Richard, ‘Epistemological Puzzles about Disagreement’, in Epistemology futures, 2006, pp. 216–36 ———, ‘Respecting the Evidence’, Philosophical Perspectives, 19 (2005), 95–119 Frances, Bryan, Philosophical Renegades (Oxford University Press Oxford, 2013) Goodin, Robert E., Utilitarianism as a Public Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1995) Kelly, Thomas, ‘Peer Disagreement and Higher Order Evidence’, in Disagreement. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009 Lackey, Jennifer, ‘Disagreement and Belief Dependence: Why Numbers Matter’, in The Epistemology of Disagreement: New Essays, 2013, pp. 243–68 ———, ‘What Should We Do When We Disagree?’, in Oxford Studies in Epistemology (Oxford University Press, 2008) Mates, Benson, The Skeptic Way (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) Nozick, R., Anarchy, State and Utopia (Basic Books, 1974) Rawls, J., A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1971) Worsnip, Alex, ‘Disagreement about Disagreement? What Disagreement about Disagreement?’, Philosopher’s Imprint, 2014, 1–20 15