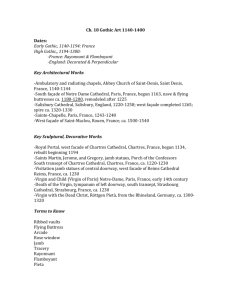

Garth 205: Chartres Cathedral

Crews 1

A mighty and impressive force, the Chartres Cathedral is over 700 years old and is a prominent piece of the small town Chartres, France. Officially finished in 1260, this massive

Cathedral has long stood as a symbol of Christianity.

1

Although Chartres’ outward appearance is pleasing to the eye, the real beauty lies within it’s interior. The immense height, large windows, and dazzling stained-glass combine to create a mesmerizing effect. All together, they force one to look upward to the celestial realm. The fundamental focus behind Chartres Cathedral’s architecture is to maximize both light and height because these elements serve as catalysts in the spiritual ways of contemplating the heavens.

While height, light, and color do work in tandem to create an intoxicating picture, it is important to see each individual aspect as it pertains to the whole. The construction of the towering Cathedral draws the eyes upward towards to ceiling, and towards God. As author

Henri Focillon believes, the nave is the best place to, “…grasp that harmonious progression of the supports…”

2

All the architectural pieces together create a sweeping, harmonious ascension within the cathedral that seems to mirror the ascension to heaven. Some even believe that

Chartres was divinely made, and writer Ernest Hauser supports this theory in saying, “Close up, the huge gray church appears more like a piece of nature than the work of man.”

3

If God seemingly built the cathedral, it reinforces that those on the inside must ponder his divine nature.

1 Ernest O. Hauser, “The Splendor of Chartres.”

Saturday Evening Post, May 28, 1960.

Accessed April 14, 2014: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1e55c1b8a856-4dfb-b586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&vid=6&hid=4202, 94.

3

2

Henry Focillon, “The Classic Phase of Gothic Architecture,” In Chartres Cathedral, edited by

Robert Branner. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 119.

Ernest O. Hauser, “The Splendor of Chartres.”

Saturday Evening Post, May 28, 1960.

Accessed April 14, 2014: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1e55c1b8a856-4dfb-b586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&vid=6&hid=4202, 94.

Crews 2

While viewers’ eyes are constantly traveling up the long arches, they also notice the vast amounts of light. This is because Chartres was purposefully built so that light would fall, “…not through narrow and deep-set windows, but through immense sheets of glass opening to the sky,”

4

This cathedral was meant to bring in the heavenly light so that one may further contemplate it.

And while the light may fall to the ground, one must remember its source is from above. This source is the sky, which infers the light is coming from Heaven. Purposeful architecture also keeps the light clear and unobstructed. The pure light pouring in through the windows is parallels Christ’s purity. He was an unsullied man, much like the light that pervades the Chartres

Cathedral. As a whole, light has a reflexive nature in this church. It illuminates and allows one to see the architecture that so clearly draws the eyes back up the impressive height of the cathedral, returning to the source of the light. Such a continuous cycle forces one to wonder about the heavenly nature of light within Chartres.

Flying buttresses allow for those massive windows and even more massive stained glass.

The vast amounts of surface area for stained glass cause the light to, “…become a cluster of jewels – a delirium of coloured light.”

5

The light within Chartres dazzles and intimidates. One cannot make sense of the array of brilliant light and colors, much like one cannot make sense of the Celestial Realm. It is beyond man’s comprehension and the light parallels this. Henry

Adams furthers this idea by stating that the light, “…radiates through the glass with a light and colour that actually blind the true servant of Mary.” 6

This sight inhibiting light is like that of

4

Henry Focillon, “The Classic Phase of Gothic Architecture,” In Chartres Cathedral, edited by Robert Branner. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 117.

5

Henry Adams, “The Twelfth-Century Glass: The Legendary Windows,” In Chartres

Cathedral, edited by Robert Branner, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 242.

6 Ibid., 235.

Crews 3 divine light. Being blinded by the light and color make the connection to the heavens an almost physical one. Adams also states that, “The windows claim, therefore, to be the most splendid colour decoration the world ever saw, since no other material…can compare with translucent glass…” 7

This infers that within the Chartres is the peak of color usage in its entirety, and colors so brilliant cannot be compared to other earthly uses of color. The divine is steeped in the colors of the stain glass at Chartres, and although man may find himself unable to understand it, that does not stop him from contemplating the colors as a reflection of the celestial realm.

All in all, the Chartres Cathedral is a wonder to behold. With light and height working together, the overall effect is mesmerizing. The colors add to light’s effect as well and these combined aspects create a mirror of the celestial realm as well as the furtherance of contemplating it. One is prompted to ponder the heavens inside the church because it is a catalyst to the heavenly realm. It is a far-reaching creation that helps one see the beauty and wonder of God. With arches so tall and colors so brilliant, it almost seems to be from another world. Chartres is a place apart spiritually because, “…the mystic beauty of its dim interior satisfies our need for spiritual values, for which our own civilization leaves so little room.” 8

This

Cathedral is for heavenly contemplation, and the nature of height, light, and stained glass serve as a means to understanding God.

9

7

Ibid., 236.

8 Ernest O. Hauser, “The Splendor of Chartres.” Saturday Evening Post, May 28, 1960.

Accessed April 14, 2014: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1e55c1b8a856-4dfb-b586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&vid=6&hid=4202, 97.

9

Phillip Ball, “A Biography of Chartres Cathedral.” First Things, February 1, 2010.

Accessed April 14,

2014,http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&sid=1e55c1b8-a856-4dfbb586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&hid=4202, 59.

Crews 4

A space much like the Chartres Cathedral in France is St. Stephen’s Episcopal church in

Richmond, Virginia. Built in 1913, it is stylistically similar to Chartres. It’s stone interior holds high vaulted ceilings and large panes of stained glass. Immediately upon entering the nave of the church, my eyes are drawn upwards to these panes, as well as the dark blue ceiling. The ceiling is reminiscent of the sky and reminds me of Heaven above. When I go to St. Stephen’s, I am going to pray and contemplate God, and the architecture of the church helps me do so.

This beautiful church has been my family’s place of worship for over thirty years. I grew up going to Sunday school every week, singing in the choir, and attending youth group programs. Spending so much of my upbringing at St. Stephen’s instilled in me a fondness for worship. When I go to spend time at my church, I feel calmer and more centered. It is a place where I can refocus my attention on what is most important to me. The church is sacred to me because of its stability and permanence in my life. St. Stephen’s is an incredibly familiar structure. When I pray, I focus on the stained glass and the light pouring through. To me, it is divine light and it pushes my eyes up towards God. The light and height of St. Stephen’s helps me to pray more fervently, while pondering my life ahead of me.

Most Christians would find St. Stephen’s to be a sacred place of worship as well. It is home to many parishioners who utilize in in similar ways. Being a church, it is inferred to be inherently sacred, with its foundations built upon religious meaning. Many types of Episcopal ritual can be found under St. Stephen’s roof. Programs on Sundays, weddings, Baptisms, and

Confirmations are all ritual practices that the church performs regularly. ENDING SENTENCE?

The inner appearance of St. Stephen’s invokes the sacred. The dazzling colors of the stained glass swirl in brilliant patterns on the floor and walls, while the gold mosaic glitters subtly. The deep blue ceiling seems vast and deep, much like the nature of God. The space’s

Crews 5 wood and stone almost envelope you in a cocoon of tranquility. Richly embroidered fabrics cover the altars and the organ’s massive pipes adorn the walls. All these aspects contribute to a heightened spiritual experience.

Inside St. Stephen’s, I feel closest to the Lord. The church is incredibly humbling and it is a sacred place I frequent when I am anxious or unsatisfied. When I am in Richmond, I visit St.

Stephen’s regularly due to the weekly worship on Sundays. Being away from the church while I am at school can be challenging, but I always feel refreshed when I am able to go throughout the school year. St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church is a beautiful place. The atmosphere, combined with appearance, creates a truly sacred environment. Much like the Chartres Cathedral, this church’s use of light and height leads to a heightened spiritual experience, and a better contemplation of the Lord. Many churches show, “…A passion for height, light, and elegance…” 10 and there are no better examples than the Chartres Cathedral and St. Stephen’s

Episcopal Church

10 Ernest O. Hauser, “The Splendor of Chartres.”

Saturday Evening Post, May 28, 1960.

Accessed April 14, 2014: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1e55c1b8a856-4dfb-b586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&vid=6&hid=4202, 97.

Crews 6

Bibliography

Adams, Henry, “The Twelfth-Century Glass: The Legendary Windows,” In Chartres Cathedral, edited by Robert Branner, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 234-246.

Ball, Phillip, “A Biography of Chartres Cathedral.” First Things, February 1, 2010. Accessed

April 14, 2014, http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&sid=1e55c1b8-a856-4dfb-b586-

7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&hid=4202

Focillon, Henry, “The Classic Phase of Gothic Architecture,” In

Chartres Cathedral, edited by

Robert Branner. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 115-120.

Hauser, Ernest O., “The Splendor of Chartres.”

Saturday Evening Post, May 28, 1960. Accessed

April 14, 2014, http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1e55c1b8-a856-

4dfb-b586-7557e6212d34%40sessionmgr4003&vid=6&hid=4202