Diseases Desperate Grown By Desperate Appliance Relieved Or

advertisement

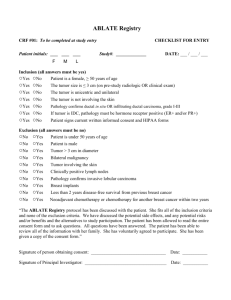

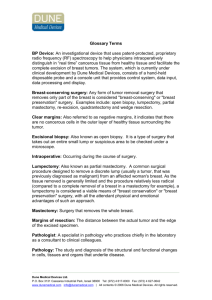

Diseases Desperate Grown By Desperate Appliance Relieved Or not at all William Shakespeare Hamlet SURGICAL TREATMENT OPTIONS Treatment option narratives are divided among the different team members. Before we start on benign vs malignant treatment, let us take a brief look at the past. For the most part the team has worked together for over thirty years. That’s over 120 years of experience working together. This work ethic has ranged from being a member of the first comprehensive breast center in the Coachella Valley to involvement in clinical trials and publishing our own results over the years in peer reviewed journals. It is my responsibility as the surgeon to inform our patients of the various options available surgically in 2014. Besides trying to preserve mind, body and spirit, one of my deep desires is that patients don’t just understand the technical aspects of a specific treatment option like lumpectomy or sentinel lymph node biopsy but understand the rationale behind such a recommendation based on over 4000 years of physicians trying to treat breast cancer the best way they knew how. There is a splendid history of breast cancer by William L. Donegan. In our library we have obtained several books and numerous articles concerning the history of breast cancer dating as far back as the first known human writings of Imhotep. He was probably the first physician (Egyptian) to write down his findings in the years around 2600BC. His story is detailed in the Edwin Smith Papyrus unearthed in 1864 although translated in 1930. Likewise the story of Leonides gives one pause as Donegan describes a surgeon in Alexandria who used hot irons to stop the bleeding during mastectomies. Needless to say my heart goes out to the doctors and their patients who tried so desperately to cure breast cancer over the millennia with nothing that approaches our scientific breakthroughs of today. If we fast forward to 1894 we find the father of radical mastectomy (William S. Halstead) operating at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He was one of the first surgeons to wear gloves although that didn’t help the cosmetic appearance of his mastectomy patients. After removing the breast and axillary lymph nodes he often extended the incision to remove the lymph nodes above the collar bone (clavicle). Further he originally left the wound that covered most of the chest open to slowly granulate in. It must have been horrendous for those women and their families. I have included pictures and operative narrative from Philip Thorek’s Surgical Techniques book (circa 1970) not that long ago on how surgeons should do a radical mastectomy. You won’t believe the contrast between that and cryoablation. Moving forward to where I started my training at Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois in 1974 we have another set of circumstances. I was trained by surgeons who the bigger the tumor they were confronted with the bigger the knife they got out. We were going to teach that tumor a lesson. We were going to use the ‘no touch technique’ and do ‘en bloc’ resections. Even just thirty years ago while we could safely put patients asleep and operate on them and close the wounds etc., we essentially had no understanding of state-of-the-art genetics or how important it would become in shaping treatment. Back then chemotherapy as well as radiation was in rudimentary form. Surgical treatment was the front line defense against cancer. Surgeons were still in control and were reluctant to give that control up. We were taught to ‘get it all’, as that was the first question that was asked coming out of the operative room besides, did she make it? In 1974, we really knew nothing about micrometastasis or occult metastasis, that is, cancer that is out there in the body (spread or metastasized) but that we can’t demonstrate on any known scans at the time. Years later in the eighties because of National Cancer Institute sponsored clinical trials we participated in, we started to recognize the importance of occult metastasis and shaped treatment accordingly. Early on in the late 1980s we participated in N.S.A.B.P. (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project) clinical trial B -18. The N.S.A.B.P. is the largest breast cancer research group in the country. It was through efforts of the membership participating in clinical trials that we began to recognize or think of breast cancer as a systemic disease, not just a localized tumor. B-18 marked the first time we gave chemotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant or primary chemotherapy). A tragic mistake we all made in our early years was looking at negative scans and pronouncing there was no cancer in evidence and that indeed we had ‘gotten it all’, only to have the patient show up with distant organ metastasis about 3-5 years later. This then necessitated chemotherapy and in the end the patient died. It didn’t make a difference if we had taken one or both breasts off or done a lumpectomy. What happens to the body is different than what happens to the breast. We are now able to control disease in the breast so it is rare to return (that is a local recurrence.) The most significant question we must ask in 2014 is, “Is it likely this particular patient has metastatic disease even though we can’t demonstrate it”. If it’s out there and we don’t treat it, she won’t do well even though the breasts will look great until the end. Fortunately, we have the means, although not 100%, to know with reasonable certainty whether a patient is likely to have metastatic disease even though we still can’t demonstrate it on scans. How do we decide this? It’s a combination of things starting with family history. What age were they when they developed breast cancer? Did the family member survive or not? The patient’s personal history also figures into this. It’s very important to look at the data on the biopsy report we call it tumor analysis. Is it an aggressive tumor? Is the Ki-67 high or low (how fast the tumor is growing)? What is the architecture of the tumor, that is, does it looks like the parent gland? Pathologists call it differentiation and they classify it as grade 1-2-3. A grade one tumor is generally less aggressive but gets more so for grades two and three. The size of the tumor is also important. For instance, a 1cm tumor (about the size of a dime) has probably been growing in the breast for about ten years on average. Probably about 2-4 years after its born a tumor starts to develop its own blood supply, if it doesn’t, it will die. Unfortunately, that’s what cancers do and it’s part of the reason they call it cancer. It’s like meatballs and spaghetti with the noodles wrapped around the meatball analogous to the new forming blood vessels bringing in nutrition. Once those new blood vessels (called neo-angiogenesis) become intimately involved with the tumor, it begins flipping out cancer cells into the general circulation. So how come if cancer cells are out there early on, why isn’t everyone dying? - because our bodies are equipped with a great immune system (assuming we are nourishing it with a healthy diet). We have what’s called natural killer cells or NK cells. Their specific duty is to seek out and kill cancer cells. Remember cancer isn’t like a snake bite where venom affects remote parts of the body. All cancer is are cells that are not following the normal growth and death cycle of the cell and eventually they divide more rapidly. When a cell comes to the end of its life’s cycle, it’s called Apoptosis (pronounced a-pop-tosis). Cancer cells don’t die when they are supposed to so eventually there are more of them. Cancer kills by simply becoming a space occupying lesion in a vital organ. There are actually about 7 steps involved with the metastatic process. (1) Growth and proliferation - The tumor has to attain a size that permits angiogenesis, (2) it has to develop angiogenesis, (3) it has to grow to a surrounding blood vessel and attach itself, invasion (4) Intravasation - it has to migrate (metastasis) in the blood vessel to a distant organ (breast cancer preferentially spreads to the bone, brain and lung first). (5) Survival of circulating cancer cells - must attach themselves to the wall of a distant blood vessel, (6) Extravastion - it must grow into the surrounding tissue and (7) Adapt to microenvironment - start the process all over. Getting back to surgical options surgeons want to know as best as possible if there is metastatic disease even micrometastais. If there is likely to be metastatic disease for whatever reasons, a decision is made in consultation with the team to perhaps give neoadjuvant or primary chemotherapy. That is chemotherapy given before surgery. Does it make any difference? That question was answered with a clinical trial run by the N.S.A.B.P. (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project) named B-18. The N.S.A.B.P. is the largest research group in the country running National Cancer Institute clinical trials. We participated in that clinical trial with Dr. Bretz as the PI (principal investigator). While it didn’t affect survival giving chemotherapy before did have a dramatic change in the size of the tumor. Overall, about 80% of the time there will be a 50% reduction in tumor size and about 30% of the time there is a complete response. The dramatic downsizing many times permits changing a mastectomy into a lumpectomy. So you can begin to see the myriad of decisions that come into play. No matter what, it is the patient who once being informed makes the right choice for her. Let’s look at the various options available in 2014. We’ll just list and discuss them, pros and cons. Before we discuss surgical options, the surgeon has to somehow obtain tissue so the pathologist can make the diagnosis. Remember, no diagnostic modality out there can diagnose cancer. MRIs, BSGIs, Mammography, Infrared, etc., can only make presumptive diagnosis but tissue has to be obtained for the actual cancer diagnosis thus making the patient eligible to be treated. Before we get into various options available for biopsy, let’s discuss a common question asked of me all the time. Doesn’t doing a biopsy of cancer spread the cells? YES it does. But in my experience of more than 30 years and literally thousands of biopsies, this has never produced tumor developing on the needle track or on the skin if we do an open biopsy and take the tumor out passing by the skin. It just doesn’t happen. You can search the literature and find anecdotal instances of tumor seeding along a needle track but it’s not something to worry about. We need tissue. How do we get it? Basically there are two ways, an open biopsy and some type of needle biopsy. Biopsy is the act of removing tissue. An open biopsy is just what it says. The surgeon makes a cut in the breast (patient is in the operating room so it’s a surgery). No matter where the tumor is in the breast, I almost always do a circumareolar incision (as small an incision as possible around the nipple). It hides the incision the best. The surgeon then just uses the cautery (to stop the bleeding) and cut around the target. The mass is removed with a forceps either with inked margins or not depending. For instance, if the patient had a prior needle biopsy that showed a benign fibroadenoma, inked margins are not necessary. There are two types of needle biopsies. The first usually done in the doctor’s office is a FNA (fine needle biopsy). It’s a relatively small needle (18g) attached to a (20ga) syringe to create suction. I always spray the skin with ethyl chloride (to anesthetize the skin without a needle) which is very cold and freezes the small portion of skin where I have chosen to introduce the needle. Cells are taken via suction and placed on slides for the pathologist. FNA is quick, inexpensive and is like a Pap smear, just cells are taken, not an actual piece of tissue. If we use the analogy of a tree, an FNA needle biopsy is likened to removing a leaf of the tree. You can tell what kind of tree it is and the general condition of the leaf but you can’t necessarily tell the physiology of the tree. That would require a limb of the tree. In our case the limb would be a core biopsy with a core biopsy needle. A core biopsy needle is almost like a straw. It’s pretty big and actually takes a fairly large chunk of tissue for not only an easy diagnosis but we can do genetic and other studies which we can’t with FNA. There are a few ways to do core biopsies. One is free hand in the office where the surgeon can feel the mass, or use ultrasound guided needle biopsy. Lastly there is either stereotactic biopsy or MRI guided biopsy. We were actually the first in the valley to introduce stereotactic core biopsy in the valley to avoid surgery. It can be done with the patient sitting or lying face down with the breast through a small hole and the computer directs the needle. So now we have tissue and the diagnosis of breast cancer and what are the options? (1) The first option is to do nothing and live with that decision. Who might want to do that? Here is a real life example from one of my patients. About fifteen years prior I had done a lumpectomy and external beam radiation on her. Fast forward, in the interim she had back surgery and woke up a paraplegic and she was now in her nineties. I hadn’t seen her for years. She called me crying that she had noticed a lump in her breast. I came over to her house with needle biopsy equipment and sure enough it turned out to be a cancer. Now standard of care for a recurrence having had lumpectomy and radiation would be mastectomy. Clearly in my hands this was not going to happen. I put her on a drug called Femara (an aromatase inhibitor), one pill a day and I came back in a month and the mass was gone. Clearly for me and her, this was the right way to go. Even if I had done nothing she probably would have died from something else. I believe not everyone needs to die with a big incision on them. (2) Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy - Brought into the mainstream by Angelina Jolie, this has become increasingly popular . Think about it, after more than 100 years and billions of dollars in research, this is what is being offered women. The story line in part goes back to the ‘did you get it all generation.’ Don’t take any chances, you had better have both breasts off and right now. The media is rather relentless with this notion, without giving other options to the women who think BPM is the only alternative. First, not everyone with BRCA 1&2 will develop breast cancer. We have had patients with the opposite result as dictated by BRCA . BRCA is about twenty years old and those two genes have been around for millennia way before BRCA came out. The effect of those genes is all in the mix of breast cancer statistics. I don’t remember reading any place that breast cancer associated with BRCA is uniformly more deadly than a garden variety breast cancer. I think it’s quite possible that a personalized surveillance program able to catch even these cancers very early thus almost guaranteeing the usual recurrence rates (about 2% for very small tumors) and a 98% survival at five years might give a particular woman pause to think if BPM is the only choice. Also there is hardly any time devoted to active prevention using a drug like Tamoxifen which lowers the risk by 50%. The other issue with mastectomy is removing the opposite breast just because, so it doesn’t come back in that breast. Again we have the ‘just get it out of me’ keen jerk reaction. It doesn’t help if the surgeon is new or just dabbles in breast cancer. Then I think the surgeon is likely to go along with such a decision. I think in over thirty years I’ve seen a synchronous breast cancer that is simultaneous cancer in the opposite breast in about two cases out of hundreds of breast cancers. It just doesn’t happen. For that matter the number of breast cancers that show up in the opposite breast years later or for that matter in the same breast as a local recurrence is just very low. After evaluating each cancer and proceeding with treatment whatever that is, that breast cancer is highly unlikely to return in the affected breast or the opposite breast. Let’s discuss the technique of radical mastectomy. I have included the pictures from Dr. Philip Thorek’s surgical book so you can see the magnitude of this surgery. Dr. Thorek was a very prominent surgeon in the Chicago area in the 60’s and 70’s. This is something the general public never sees. It depicts an incision from the umbilicus (belly button) to the shoulder. It involves not only removing the entire breast but the muscles underneath (pectoralis major and minor). In conjunction with that most of the lymph nodes are removed. The average number of nodes removed around the country in an ALND (axillary lymph node dissection) is between 12-15. The most lymph nodes I removed at one time were 58. I wish now I had never done that but that’s the way we were trained back in the 1970s. Of course, we have had Sentinel Node biopsy for several years now where only one or two nodes are removed. During my residency suggesting that a surgeon could only remove one node would have been met with much distain and disbelief. Mastectomy in my opinion was the result of incorrect thinking back then that breast cancer started in the breast and spread by direct extension to the first lymph node then the second in a very orderly fashion. The message was clear. Say two nodes were involved, if the surgeon could get to the fourth one, that was it, he would have gotten it all. Back then if your patients didn’t do well you were not taking enough tissue. So on it went for decades and some are still doing it. There are now a couple of new players in the mastectomy arena. One is the skin sparing mastectomy and the other is the Oncoplastic mastectomy surgery. The skin sparing mastectomy is just what it says, instead of removing the nipple and the skin around it (to the extent the surgeon can close the wound, all that skin is left including the nipple). It can be argued that it’s a better cosmetic result and, of course, a tissue expander is inserted either immediately or a few months later awaiting an implant. In all my years I’ve never seen a subcutaneous mastectomy with an implant really look good up close and personal. It’s always lumpy and indented because the surgeon can’t precisely divide the tissue immediately beneath the skin circumferentially equal. If you’ve been paying attention, the reason for the mastectomy and in some cases the skin grafting is to remove as much tissue as possible to prevent a recurrent cancer in that breast. You should be saying to yourself, wait just a minute. If the idea is to remove as much tissue as possible thus lowering the chance of recurrence, how does the surgeon know if he/she has left too much tissue behind? Yes, it’s a problem, did I take enough tissue or should I leave some more behind for a better cosmetic result? They bend the rules for mastectomy it seems to me, no black and white. About five years ago they came out with Oncoplastic Surgery. For decades plastic surgeons were the only ones that handled implants and reconstruction after mastectomy. Now for some reason there is a new drummer beating the mastectomy drum and I think it has to do with remuneration. Why after decades do general surgeons want to get into more mastectomies with reductions and implants? There is only one reason to me, dollars. Let’s turn our attention to ALND (axillary lymph node dissection). First, why even care about lymph nodes and what are they? We care about the nodes because that is one of two paths the cancer can take when it reaches the metabolic potential to metastasis (spread). Notice I said metabolic potential instead of size. Small tumors can spread and larger tumors can just sit there it. It is dependent on their genetics and ability to grow new blood vessels. It’s true though that generally if tumors are very small (below 1cm) their potential to spread is less, and if they are about 5mm or so (the size we are intend on finding), the metastatic potential is almost nil although not zero. Remember, breast cancer that’s around 1cm has been there on average about ten years growing from a single cell. We have known for a hundred years that breast cancer spreads to the lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are part of the immune system responsible for making antibodies against disease and also clean the blood. They respond to disease and cancer by enlarging to do their work and eventually become totally replaced by a tumor if nothing has been done. I was taught to get every last node. The most I have ever taken out of someone’s axilla was 58. I never do that kind of operation anymore. The average number around the country removed during an axillary node dissection is twelve to fifteen. It has also been long known that the number of lymph nodes involved relates to survival. The more nodes involved the worse the survival. At some point the surgeon no matter what they do doesn’t help. The problem with positive nodes is that the lymphatic system flows directly into the blood stream and thus seeds the entire body. Lymph nodes can be very small like the size of a pea or larger like a plumb if involved with tumor. About fifteen years ago Sentinel Lymph Node biopsy came onto the scene. The idea of a sentinel node is like a guard outside a castle. You can’t get into the castle without going by the guard. When cancer cells enter a lymphatic vessel traveling on their journey to the vascular system and beyond, they don’t have a little motor on them like a small boat. They proceed down the easiest path every time and that cancer cell will end up every time at the entry node, the Sentinel Node. So it was reasoned that if we could somehow find that node at surgery (do a frozen section) and it was reported by the pathologist to be negative, the surgeon didn’t have to take out any more nodes and thus have much less in the way of adverse side effects like nerve damage, shoulder pain, arm pain and lymphedema (swelling of the arm). Frozen sections have been used for decades by surgeons and pathologists wanting to verify cancer and obtain clean margins. That is, the surgeon wants to get the cancer out with say a lumpectomy with a margin of normal tissue around it circumferentially. If I’m doing a lumpectomy and sentinel node, I’ll do the sentinel node first, judge what it looks to be benign or has cancer, judge how it looks and feels and then sometimes I’ll close that incision and move to the breast and await the pathologist word. It makes the operation go faster. If the sentinel node is positive then most surgeons will proceed with an ALND. There are nerves we all try to avoid. Injuring one of them can lead to what’s called a winged scapula (the shoulder blade bone in your upper back). That nerve is the long thoracic nerve, or if you want to go back into history, it was called the long thoracic nerve of Bell (Sir Charles Bell a Scottish surgeon on the 1700s). It’s the size of a strand of spaghetti pasta. It runs along the side of the chest wall on the serratus anterior muscle and can be easily identified by looking for it and lightly pinching it with a forceps (the muscle will move). Another nerve we try to avoid is the thoracodorsal nerve. It is also called the long subscapular nerve and it innervates the latissimus dorsi muscle, the big muscle in the back that looks like it fans out in body builders. Same thing here you identify it and pinch it and the muscle moves, it is lateral to the long thoracic nerve. I have inserted a picture of that area below. Both the above nerves are motor nerves, that is, they move the muscles they innervate. There is a sensory nerve we also identify called the first intercostal brachial nerve. It kind of hangs in the fat pad of the axilla that contains the nodes and its course is variable. It can sometimes divide early into multiple branches or late with a larger main branch. I have always tried to preserve it if possible. If it has to be taken for whatever reason, it causes numbness on the inner aspect of the arm. I never have had long term problems with it either way. There are a couple of other nerves, the medial and lateral pectoral nerves that innervate the pectoralis major (the big chest muscle) but they are usually well out of the way unless the fat pad is what we term ‘socked in’ with adherent tumor making any dissection difficult. There are multiple small veins that can be taken without consequence. The fat pad is taken down using blunt and sharp dissection from the axillary vein (the big vein returning blood from the arm). The fat pad is about the size of the palm of your hand. Once it is removed a final check of the field is done by both visual and by palpation to make sure that the tissue you want removed has been removed. This is followed by placement of a drain that is removed after a few days. The drain is necessary as unlike small veins that are ligated, the lymphatic vessels are very small and can’t be individually ligated. Therefore, lymphatic fluid drains at the operative site and closes off in a few days. The more tissue that is removed, the more likely it is that lymphedema will develop chronic swelling of the arm necessitating constant massage and wearing a compression sleeve forever. At the end usually one or two drains are placed in the mastectomy site because of the large amount of raw tissue immediately under the skin. I close any incision with a subcuticular stitch so there are no stitches visible on the skin and therefore no ‘railroad tracks’. It’s just something I do, not all surgeons take the time. By the way I can’t really recall my last mastectomy. With being able to downstage most of these larger cancers with chemotherapy (shrink them thus turning what would have been a certain mastectomy into a lumpectomy), for me a mastectomy is very, very rare and mostly of historic value. One last mastectomy is called a simple mastectomy. In this procedure only the breast is removed for whatever reason perhaps extensive DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ). Now a days however, with sentinel node biopsy in vogue some surgeons take a node or two (with the simple mastectomy) since about 5%of the time DCIS will have a node involved by an occult invasive cancer not recorded elsewhere. (3) Lumpectomies The year I completed my surgical residency (1979) lumpectomies were just starting to be done in this country. Dr. Unberto Veronesi from the Tumor Institute of Milan in Italy published his seminal paper on the first trial comparing mastectomy to lumpectomy and radiation. The results were the same. But it’s taken essentially my whole professional career to get that point across to every surgeon in the country. Now with prophylactic mastectomies and oncoplastic mastectomies it seems we are reverting back to pushing mastectomies. At this point it might be worth mentioning that virtually every advance in breast cancer has come out of Italy. Not only did lumpectomies come from there but the concept of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary chemotherapy (chemo given before surgery to shrink the tumor). Researchers in the U.S. (in my opinion) spent decades and hundreds of millions of dollars just to confirm those results which in the end they did. Probably because we wouldn’t accept the Italian’s paper (which was a good paper), they had to justify their getting hundreds of millions of dollars from the government to run clinical trials and most probably hundreds of thousands were submitted to mastectomy that didn’t need it. This seems like a good place to bring another fight I’ve been fighting for two decades now, that is getting so called breast centers to not only work together on a national level but to have a means (say a fax machine) to let all centers know at once about important clinical findings to change treatment right then and not take decades like lumpectomy did that because of independent action of surgeons sacrificed hundreds of thousands of breasts that wouldn’t have been done if we had a network in place. Many people very much dislike the term ‘breast czar’. But in reality we had a drug czar and the like and I really wanted a microphone in some person’s face, man or woman, to tell the American women just what should be going on. Currently there is no such person in charge and all centers pretty much do their own thing. Lumpectomy is basically a glorified breast biopsy. Unlike a biopsy for benign tissue, during lumpectomy the surgeon strives to obtain ‘clear or negative margins’. That is, no cancer circumferentially (either on frozen section or permanent section) in the adjacent tissue around the tumor. There is some continued debate as to just what constitutes a clear margin? Is it 1cm or 1mm. Of course, radiation therapists cringe if the margins are very close but technically negative. While one can get support for most any position in the literature, it is quite rare (in my personal experience anyway) to have a local recurrence when we get through doing whatever we deem necessary to the breast. This may just include a lumpectomy without radiation or chemotherapy before or after lumpectomy followed by radiation. It’s all in knowing what that tumor is capable of and that involves the pathology and genetics of a given tumor. Immediately prior to surgery if the tumor is not palpable (can’t feel it) and for example just see it on mammography or u/s, usually the radiologist will insert a wire to direct the surgeon so a lot of tissue needn’t be taken. This is done with local anesthesia and generally tolerated very well. Some teams like to put blue dye (methylene blue) to further help the surgeon. At times calcium deposits are not easy or impossible to see at surgery so the surgeon is totally dependent on that needle localization. Why it’s called ‘needle localization’ it’s actually a wire that gets left in the breast. It’s fairly long and has a hook seeing, collar and tail and once placed it doesn’t move so the surgeon knows by looking at the mammogram when he/she comes upon the wire exactly where the target is. It gives the surgeon knowledge he/she wouldn’t have without the wire. Therefore with the wire the surgeon can gauge (what we call stereoscopically) just where the target is and how much tissue needs to be removed. Hopefully then the surgeon gets out the lumpectomy specimen in one piece and without seeing the tumor. Once the tissue is out the surgeon should identify the margins so the pathologist can accurately identify them on frozen section. The method I have always used is that the short stitch is at 12 o’clock, medium stitch is three o’clock and the long stitch is anterior. That way there is no confusion over margin locations. The pathologist will receive the tissue in about ten minutes and take another twenty or so minutes to do the frozen section. The pathologist generally use dye to identify the margins. Then when the pathologist calls into the OR (while the surgeon is still operating) and says for example, there is cancer extending to the 6 o’clock position, the surgeon knows exactly where to take the tissue and mark the new 6 o’clock margin and so on until all margins are clear. That’s called the process of a frozen section. One caveat about sentinel node frozen sections, or for that matter about any frozen section. Remember all this takes place while the patient is asleep so there isn’t time to dilly dally. When the pathologist receives a sentinel node, it is examined both visually and by palpation. The literature is replete with data that supports the more sections (slices of tissue just like a butcher cutting extra thin roast beef) a pathologist does the better chance they will find cancer if there is any to find. But all that takes time and so they rely on their experience to decide where to make a few cuts while the patient is in the OR. This happened three times in a year to me. The pathologist calls to the OR saying that the node is negative. So I close up and about three days later I get the final or permanent sections that say there are literally 3 or 4 cancer cells in the node thus making it technically positive or an occult cancer or micrometastasis. To get that a couple of things happen. After the surgery the pathologist stains the tissue with what is called Keratin staining. Using immunohistochemistry techniques (which takes a couple of days) the pathologist has a tool that can actually pick out individual cancer cells in the sliced node. The other thing is the pathologist actually sections the entire node where during surgery they might only do a more suspicious area. What does a technically positive node mean? To some surgeons it means an additional surgery to remove more nodes and to others it doesn’t. How come? There is a hot debate about what to do in this circumstance. A while back there was a nice paper on this very topic by a surgeon at the Mayo Clinic. I called him to discuss those three cases. He said, “Phil what did you do?” I said, “I took all three back for further node removal”. He said, “I bet you didn’t find any more additional positive nodes did you?” I said, “No”. He said, “I wouldn’t have taken them back”. This was a few years ago so now I don’t go after nodes like that again unless the patient really wants to know so that taking out ten additional negative nodes will help her psychologically. Any drains come out usually in about a week or less. The axillary drain for example might drain mostly blood tinged fluid for a day or so then changes to a clear yellow that is just lymphatic fluid. Most of these surgeries can be done as an outpatient, even a mastectomy if the patient is up to it. All skin closure is done with subcuticular stitches so you can’t see them. You can also see that there are multiple considerations that come into play before, during and after surgery. Let’s talk about cryoablation. What makes me and the other surgeons doing this able to do so comparatively little and still have the patient enjoy a full life free of breast cancer and unscarred? If you consider all the different procedures we discussed, essentially they have one thing in common. Over the years following thousands of patients and multiple clinical trials the results are basically the same for mastectomy to lumpectomy, from axillary node dissection to sentinel node, from external beam radiation to APBI to IORT. Please review the section on radiation therapy done by Dr. Mantik, a true master of this modality. He’s seen it all and done it all. It’s one of the only things about growing older is your vast experience which is hard to beat. Cryoablation (killing a cancer by freezing it) has been around for many years. Like newer technologies, once it came out the quest was on to make it better. Initially it was used on cancer that was spread to the liver. Liver resection, especially an extensive one, is fraught with complication including bleeding to death on the operative table. So by simply inserting a cryogenic probe, it obviated the bleeding and other problems. Initially the cooling agent used was Argon gas as it was inert. The problem was the Argon took a long time to cool down the tissue. Another reason cryoablation never really took off was it didn’t extend life as in the patients with cancer in their liver. Finally they were asking the surgeon to not do surgery. It takes a different mind set by the surgeon to abandon what has proved successful to try something else. There were never any big clinical trials with cryoablation. Fast forward to today and we have an entirely new setup including liquid nitrogen which gets very cold very quickly almost -200 degrees C. The technology is from a relatively new company from Israel (IceCure) with headquarters in the U.S. They have really perfected the process of cryoablation so the kill zone forms very quickly (in a minute or two) and expands rapidly to encompass circumferentially the tumor with wide margins all around the tumor around 1.5cm. The procedure usually takes about 20 minutes with no sutures or even steri-strips. We have seen then the evolution of cryoablation in IceCure. There are some who feel cryoablation has been tried and hasn’t worked all that well, very similar to infrared’s experience in the 70s. In both instances it’s apples and oranges. Both later products are far removed from their fledgling predecessors. Infrared for example is now digital and incorporates the artificial intelligence which wasn’t in existence in the 1970s. Likewise the change over from argon gas to liquid nitrogen with state-of-the-art graphics and developing a hi-tech probe has made all the difference. Agreed there are no long term data of the efficacy of using the new liquid nitrogen probe. However, if back in the late 1970s some surgeons weren’t willing to try lumpectomy, we would all still be doing mastectomies as the treatment of choice and not know any better like previous generations. There are only a few surgeons in the country who are attempting to use cryoablation on breast cancer. At this point in time, 2014, it’s probably safe to say the selection of patients for the cryoablation procedure is fairly stringent, that is, we are not taking on all comers. Currently the tumor should be ideally less than 1cm in diameter and have a less aggressive profile on pathology and genetics with a low recurrence rate on OncotypeDX, a genetics recurrence risk profile (to be discussed later). Having said that there is a difference between pure science and where science meets the road dealing with humans. The largest tumor I’ve done with cryoablation is 1.7cm and there were pressing reasons to do it. I feel it is the surgeon who should always treat the patient and not statistics. The cryoablation procedure itself is carried out in the office. The patient is given the multipage informed consent days before and has an opportunity to ask questions so that aspect is all taken care of when they come to the office for the actual procedure. The patient a valium about two hours before which takes the edge off. Although I am the one who inserts the local anesthesia and probe under ultrasound guidance, I need the help of three other people. One actually flies in from Detroit for each procedure. There are two representatives from IceCure (Susan and Haig) and I have an expert in ultrasound (Sylvia from Hitachi) to help keep track of the tumor while I insert the probe. First, we prep the area and put a drape on the breast. Then we localize the tumor to determine its exact location and longitudinal axis. Ultimately I want to shish-kebab the tumor on its longitudinal axis with the probe. The area is then infiltrated with lidocaine local anesthesia from the chosen entrance site to around the tumor. Local anesthesia is given as needed although most have been fine with just the first infusion. Next a small 2mm stab wound is done at the entrance site and the probe inserted. It is advanced under ultrasound guidance. This step usually takes about three or so passes. The smaller the tumor the harder it actually is to accomplish the task but accomplish it we have done on all cases thus far. The probe is advanced through the tumor so the tip is about 1.5cm past it. This is done because the freeze ball commences just by the tip and we want not only the tumor engulfed by the freeze ball but a very wide margin in the kill zone. Once I have the probe in the ideal location and the team agrees, I push the little blue button and the liquid nitrogen is infused into the probe and the freeze ball grows immediately. This growth of the freeze ball is rapid so it’s game on when I push that blue button. As the freeze ball grows, we want to keep it away from the skin. The forming ice ball is about -180 degrees Celsius or about -292 degrees Fahrenheit, really cold. If you saw the James Bond film, Golden Eye, there is a scene where an explosion takes place of a large liquid nitrogen tank and the nitrogen goes all over the one bad guy and freezes him solid. Therefore, we want it to engulf the tumor but not touch the skin. If the tumor is close to the skin it can pose a problem. The solution (pun intended) is to infuse saline (salt water which doesn’t freeze) between the tumor and the skin. It forces the tumor down away from the skin. So we monitor that space all during the procedure and inject saline as often as necessary. This action and the probe usually causes some extravasation of blood into the surrounding tissue (temporary) which causes ecchymosis (black and blue) tissue. Oddly enough pain hasn’t been a big issue. Ideally we want to see an ice ball about a 4cm (about an inch and a half) on either side of the tumor. It’s almost like putting a pea in the palm of your hand and your palm represents the ice ball. That’s the kill zone. If we are trying to cure the breast cancer without radiation (which mostly we are), then we want that ice ball to grow to the 4cm. While the radiation therapist might say I’m encroaching on his turf, here the decision about radiation is a decision where the surgeon has some say, like the patient. For more than a 100 years we were taught the dogma that only six weeks of external beam radiation would do and that these breast cancers with multicentric tumor (tumor in more than one place in the same breast) not radiate the entire breast was to leave cancer behind that eventually kills the patient. Let’s see if that’s true. About fifteen years ago APBI (accelerated partial breast irradiation) came out. That is, there was a balloon at the end of a special catheter (like a foley catheter to collect urine) and it allowed a special radiation wire to go down it that would radiate circumferentially around the lumpectomy bed. It would radiate the entire lumpectomy bed to 1cm (about the size of a dime) assuming the balloon came in contact with the tissue. If there was excessive space, just air or fluid would be radiated. A CT scan verified the placement and skin spacing (from the balloon to the skin had to be at least 1cm). The rational for this procedure is that about 90% of the local recurrences occur within 1cm of the original lumpectomy margins. Just like lumpectomy there was an outcry that without external beam radiation viable tumor would be left behind and eventually kill the patient. I have personally performed about 40 or so of these procedures. I invented a surgical procedure to augment partial breast radiation. The procedure is published in ASTRO proceedings 2009, the largest radiation therapy group in the world and it was selected for a poster presentation. The idea here is that if the skin spacing is less than a 1cm, then the patient can’t have APBI because the skin would be involved with the radiation. I came up with the idea to put a free fat patch harvested from the abdomen as a sort of buffer between the catheter and the skin thus enabling that particular patient to have APBI. I mentioned the outcry about leaving tumor behind without external beam radiation. Well, after fifteen years if that were true we should be seeing thousands of women with local recurrences and we are not. I have never had a local recurrence at the lumpectomy site with any of my personal APBI patients. The same outcry came about the same time with those who opposed sentinel node biopsy that tumor would be everywhere if you didn’t take out all the nodes. Back then and currently for surgeons just starting sentinel node biopsy, how many times do you think the surgeon just missed the node altogether and took another node, not the sentinel node? Probably a heck of a lot of times a surgeon actually missed the sentinel node in the rush to say to his/her community – yes I can do a sentinel node biopsy so the patient would stay in their service. So given that how is it fifteen years later we are not seeing thousands of women with local recurrences in their axilla? Not all is black and white and that is why we can manipulate breast cancer (usually) so the big concerns of the past necessitating external beam radiation and axillary node dissection aren’t necessarily needed to have a great result. Now we come even closer to the rationale for using cryoablation. Coming off the APBI success the doctors at the Tumor Institute of Milan, Italy recently pioneered IORT (Intraoperative radiation). In this procedure the surgeon performs the lumpectomy and then while the patient is still asleep a special radiation machine comes in and the radiation ball is placed into the lumpectomy cavity and the patient undergoes radiation for about thirty minutes. So when she wakes up in the recovery room, she is finished with surgery and radiation. Think about that. Thirty minutes is now equivalent to six weeks. How can this be? Decades and decades went by and hundreds of thousands of women and how is it that it took so long for doctors to adventure into something like APBI and now IORT? The establishment takes so long to bring things to light. Once the probe is correctly placed and everyone agrees, I push the little blue button and the iceball commences immediately. There is nothing to do except watch the skin spacing. The probe isn’t moved for twenty minutes or so. We go through three cycles, about eight minutes of freezing, followed by about eight minutes of thawing and lastly another eight minutes of freezing, so the iceball reaches about 4cm totally encompassing the tumor. We watch the monitor that tells us the minutes and temperature. The reason for the thawing phase is that thawing changes the extracellular (outside the cells) milieu (environment) in such a way as to cause the cells to burst and die right then. The second round of freezing is to put the frosting on the cake as it were killing every last cell. Once the three phases are complete the system tells us when to remove the probe. Once removed that completes the procedure. There are no sutures or staples or even steri-strips. The actual stab wound for this is about the size of this bar _. I have put a small dab of antibiotic ointment on it but that’s it. The patient resumes normal activity. In fact, I have nicknamed the procedure, ‘The Lavender Procedure’. So called because they usually feel so good we all go across the street to the Lavender Restaurant and have dinner. One of the first patients felt that way and within twenty minutes she was having lobster salad and chardonnay instead of her predecessors waking up in a hospital recovery room with their breast off and in pain wondering what hit them. When they toasted me I got a little teary eyed. Being able to actually do those first cases was the culmination of years of research. I felt as though I was on hallowed ground. I usually follow up in a week and do ultrasounds then and a month later and a mammogram at about 3-6 months. About now we are starting to do repeat needle biopsies to make sure the cancer has been totally killed off in the breast. For those interested, I have included the informed consent in another section. The procedure is almost like a child birth in that everyone can participate as they see fit. For instance, one patient’s daughter who was very interested in seeing this couldn’t actually make it that day so the patient gave her a description of the goings on via cellphone. Another patient’s husband held her hand and watched the entire process. This is a big change, paradigm shifting for sure. We are able to do this for a total cost of $2,000.00 instead of around $250,000 for extensive surgery, prolonged chemotherapy and radiation. You can now see the myriad of factors that enter into just surgery. But for me personally these are the easy hurdles to jump, it’s all the increasing paper work and never ending regulation outside of this that’s the real problem for doctors. I had dinner with Dr. Mantik (our resident radiation therapist) recently and he had an observation that with this new Lavender Procedure that we were now presented with an entirely new set of issues. Basically everything would have to be rethought, everything. Hopefully a major clinical trial will somehow evolve within the system like N.S.A.B.P., and bring cryoablation into the light of day. There will probably be a turf war between radiologists and surgeons as to just who should be doing cryoablation. For that matter your own family physician could do it if they wanted to become skilled. That’s part of the beauty of this. Basically any doctor could do it. It’s not delicate brain surgery. Considerations like this are important in developing countries where highly skilled surgeons or radiologists are either non- existent or in very short supply. Should you have any questions just ask.