Methods of comparative linguistics

advertisement

Methods of comparative linguistics

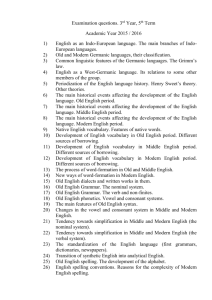

19th Century and Historical Linguistics

By the end of the 18th century the scientific progress in all spheres of life accumulated

such enormous quantities of new data that some kind of categorisation had to be

made, the process that culminated in the theory of evolution formulated by Charles

Darwin (1859), which explained the transmutation of species through natural

selection in the struggle for survival.

Linguistics was not unaffected by these movements and trends in natural sciences.

The entire 19th century was dedicated to the reconstruction of the evolution of

languages from their ancestor language, and to the discovery of rules and patterns of

changes that made this evolution possible.

There are different sources of similarity among languages. The first source is chance.

Although they sound similar, the Greek theós and Latin deus are not related. The

similarity is accidental. Latin deus is cognate with the Greek Zeus (genitive Dios).

Another example of chance similarity is Greek mati ‘eye’ , Malay mata ‘eye’, English

bad and Persian bad etc.

The second source of similarity between two languages is borrowing. The English

igloo is similar to Inuit iglu because English borrowed this word along with the

concept of the house made of snow. The Iranian word baga ‘god’ was borrowed from

the Slavic neighbours.

The third source of similarity is language universals. Onomatopoeic words (cuckoo,

Kuckuck, kuku), baby-talk words for kinship terms typically containing syllables ma,

ba, pa, da, ta...)

But sometimes the similarities among languages go beyond chance, borrowing or

linguistic universals.

The idea that languages might be related to each other through descent from a

common ancestor was in Europe proposed already by Dante. The similarities among

Romance languages were so overwhelming, that, given the common historical

background, it was not difficult to determine Latin as their ultimate source.

Spanish

Italian

French

Portuguese Latin

1

uno

uno

un

um

ūnus

2

dos

due

deux

dois

duo

3

tres

tre

trios

três

trēs

10

diez

dieci

dix

dez

decem

am

soy

sono

suis

sou

sum

are

eres

sei

es

és

estis

is

es

è

est

é...

est

fish

pez

pesce

poisson

peixe

piscis

cuore

coeur

coraçaõ

cor

heart corazón

Attempts to make longer-range comparisons were less successful. In Europe, it was

believed that all languages were ultimately descended from Hebrew, in India from

Sanskrit. But at the end of the 18th century, an important discovery was made by Sir

William Jones, a British judge, philologist and scholar in Calcutta. He became

fascinated by Sanskrit, the classical Indian language, and its similarities with Latin

and Greek. He concluded that these languages had evolved from the same parent

language, and that Celtic and Germanic languages could be added to the family.

Jones sent his findings to Europe, where they attracted the attention of Franz Bopp,

Wilhelm von Humboldt, Jacob Grimm, Rasmus Rask and Friedrich Schlegel, who

dedicated their work to establishing the genealogical tree of Indo-European

languages and reconstruction of their parent language. They applied the so-called

Comparative method

The proof of genetic relatedness is that similarities are systematic and recurrent:

English

German

a) p : f

Pound

Pfund

Penny

Pfennig

Ape

Affe

b) k : x

Make

machen

Cook

Koche

According to most linguists, the ultimate proof of the relatedness of languages lies in

the reconstruction of their ancestor or PROTO language, from which the attested

forms can be derived by plausible linguistic changes.

The ancestor forms can be reconstructed from the extent attested forms:

Spanish diente

Italian dente

French dent

Portuguese dente

All words begin with d-, which means that their ancestor must have begun with d-. All

words have the cluster –nt- (pronounced in older French). The ancestral word must

have had d.....nt....

Italian, French and Portuguese have -e-, Spanish has –ie-. Three languages have the

vowel –e at the end of the word, one none. Based on that, it is relatively safe to

assume that the ancestor form was *dente (classical Latin dēns, stem dent-)

If that be true, than one must find other examples of the same correspondences

Spanish

Italian

French

Portuguese

Latin

viento

vento

vent

vento

ventos

Groups of words which we compare are called correspondence sets, and individual

words in the sets are cognate words. When sounds correspond across a number of

correspondence sets, we speak about the regularity of sound correspondences. An

ancestral language is called a proto-language and its descendents are daughter

languages.

We also have to find a plausible explanation for proto-Romance *e to have changed

to ie in Spanish. The fact that Latin language developed into more languages is due

to language change. When the sounds of a language change, one speaks of sound

changes. Sound changes are regular and exceptionless. This view is called the

Neogrammarian Hypothesis. It is crucial for determining the pronunciation of earlier,

proto stages of languages.

In doing so, one must consider all facts available: contemporary description,

descendant languages, orthographic practices, including misspellings, borrowings in

other languages etc.

A more complex example (Indo-European vowels):

Gothic ita

(it)

<

IE *i

Latin idem

Sanskrit idam

Gothic ist

(is)

< IE *e

Latin est

Greek esti

Sankrit asti

Gothic

juk

(yoke)

Latin iugum

Greek zugón

< IE *u

Sanskrit yugam

ON aka (drive)

Latin agō

Greek ágō

< IE *a

Sanskrit aǰati

Gothic ahtau (eight)

Latin octō

Greek oktō

< IE *o

Sanskrit aṣṭau

Gothic fadar

Latin pater

(father)

< IE *ə

Sanskrit pitar

In reconstructing proto-sounds, several principles have to be observed:

a) Reconstructed items (sounds) should be natural.

b) The phonetic value should be attached to a reconstructed sound.

c) The reconstruction must not violate the Ockham Razor (cannot presume *

instead of *i.

During the 1950’s, and all through the 1970’s, a different method promised to make

the establishment of genetic relations among languages easier than the traditional

comparative method. This GLOTTOCHRONOLOGICAL or the LEXICOSTATISTICAL

method was proposed by Morris Swadesh. Just as the comparative method, this

approach was also modelled on the method applied in natural sciences, the so-called

Radio-Carbon method, which operates with a constant rate of change (the half-life of

different carbon isotopes in a carbon-based material. Glottochronology is based on

the assumption that the core of the basic every-day vocabulary of a language is

replaced at a constant rate. It was first tested against the lexical loss in languages

with a long series of texts, like Romance languages. The final conclusion was that

80-85 percent of core vocabulary is replaced over a thousand years. According to

this method, Modern English has preserved 80% of the basic vocabulary in the year

1000. The method seemed promising because it required only the collection of basic

vocabulary items. But the enthusiasm soon came to an end.

PROTO-INDOEUROPEAN LANGUAGE AND INDOEUROPEAN LANGUAGES

Despite the shortcomings of the comparative method, it played a decisive role in the

reconstruction of the common ancestor of languages which are commonly referred to

Indo-European languages. The reconstruction had been practically completed by the

end of the 19th century, although some languages, like Anatolian languages and

Tocharian were discovered as late as the 20th century.

As to the time and location of the Proto-Indo-European language, the most widely

accepted estimates are 3700 BC and the Pontic-Caspian steppes of Russia. The

vocabulary common to Indo-European languages suggests that their ancestral

society was patriarchal, stratified, cattle raising and possibly agrarian.

For a long time it was believed that IE relatively soon split into two dialects which

later evolved into two branches of languages: the satem (or eastern) and the centum

(or western) group respectively.

The division is based on the development of Indo-European velar consonants.

PIE had the following inventory of stops: labial, dental, palatal, velar and labio-velar,

all of them voiceless, voiced and aspirated voiced.

Labial

dental

palatal

velar

labio-velar

Voiceless

p

t

k̂

k

kw

Voiced

b

d

ĝ

g

gw

dh

ĝh

gh

gwh

Voiced asp bh

The three series of velar stops collapsed into two groups in all IE languages.

In eastern languages, the labio-velar and the velar stops coalesced, in the western

group the palatal and the velar stops coalesced into plain velar stops.

PIE *k̂m̻tom- > Skt. śatám Av. satəm, OCS sŭto

Lith. šim̃tas

Gk. Hekatón Lat. Centum, OIr. Cēt Goth. hund

Eastern group (Satem languages):

Indo-Iranian (Aryan) languages

Aryan < ārya ‘noble'

Indo-Aryan (Indic):

Indic tribes entered India in the second millennium BC, from the Iranian

plateau into Punjab. The Indus river valley had already been the site of urban

civilization, possibly Dravidian, flourishing in the latter part of the 3 rd

millennium.

The oldest Indic language is Vedic Sanskrit. This is the language of the sacred

books of Brahmanism, Vedas (véda ‘knowledge’). The oldest one of them,

Rig Veda, contains over 1000 hymns in 10 books. It was completed by the end

of the 2nd millennium BC – difficult to decode, in intentionally obscured

language.

In the 5th century BC Pāṇini made a highly precise description of Sanskrit, in a

manner resembling modern generative grammar. This grammar fossilized the

written language, Classical Sanskrit, which survives in Mahābhārata and

Rāmāyaṇa.

Sanskrit kept voiced aspirated stops and developed retroflex dentals (including the

nasal).

Middle Indic or Prakrit evolved into mdern indic languages Pali, Hindi-Urdu,

Bengali, Punjabi, Sinhalese, Romany, Gujarati, Kashmiri, Sindhi, Sinhalese...

Iranian branch of Indo-Iranian languages:

Avestan (7th BC), the language of Avesta, a collection of sacred texts of the

Zoroastrian religion (Mazdaism).

Zoroaster or Zaraθuštra lived in late 2nd millennium BC. His teachings introduced

cosmic dualism with two deities: Ahura Mazda (wise lord) and Ahriman (destructive,

evil spirit)

Old Persian – inscriptions about Darius I and Xerxes I (1st millennium) were written in

a cuneiform script (trilingual – Akkadian, Elamite).

Middle Iranian or Pahlavi evolved into modern Iranian or Farsi, which came under

Arabic influence when Iranians accepted Islam.

Other Iranian languages are Kurdish, Pashto, Ossetic, Tajiki, Baluchi,

Albanian

Albanian speakers believe that they are descendents of Illyrians, an Indo-European

people who settled the western Balkans in the 2nd millennium BC. Three main

varieties are spoken today, Gheg in Kosovo, Tosk in southern parts of Albania and

Arbëresh, the dialect of Albanian minority in Italy. Albanian shares several linguistic

features with the neighbouring languages, which form the so-called Balkan

Sprachbund e.g. postpositioned article, the loss of infinitive after modal verbs etc.

Armenian

In the past, Armenian was listed among Iranian languages, but this theory was

disproved in 1877. Armenians were converted to Christianity around 300 AD. Mesrop

(360-440), a charismatic priest and linguist, devised a special Armenian script, based

on Greek alphabet. This gave rise to Armenian literature, the translation of the Holy

Scriptures in 411 and the consolidation of the national Armenian Church as the

backbone of Armenian identity. The classical Armenian Grabar remained the literary

standard until 19th c.

Balto-Slavic languages

Baltic and Slavic languages probably share a common ancestor, Balto-Slavic.

Slavic languages were first mentioned in Byzantine records in 6th c. AD.

They

are

divided into three groups, East Slavic, West Slavic and South Slavic languages.

The literacy of East Slavic languages began with the Christianisation of Rus’ in 988

by the pupils of Constantine and Methodius in a language close to Old Church

Slavonic (> Russian Church Slavonic). This language is still used in the Orthodox

liturgy, as a literary standard it survived until the 17th century. East Slavic languages

are Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian.

West Slavic languages are Polish, Czech, Slovak ad Sorbian. Polish stands out with

its nasal vowels, Czech and Slovak had the same literary standard until the 19th

century. Sorbian is spoken by 155.000 people along the river Spree near Dresden.

South Slavic languages are Slovene, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian and Bulgarian.

Old Church Slavonic, spoken by Constantine and Methodius and their disciples, was

also based on south Slavic dialects from around Thessaloniki. The old Bulgarian

language was similar to Chuvash, and it belonged to the Turkic language family.

Baltic languages are the extinct Old Prussian, Lithuanian and Latvian. Old Prussian

is preserved in translations from 17th century; it was spoken until the 18th century on

the territory of eastern Prussia. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, Prussians were

converted to Christianity by the Teutonic Knights, a religious and military medieval

order. Christianization was combined with intense Germanization. Of the two

surviving Baltic languages, Lithuanian is the one which has kept most of IndoEuropean features, like tone accent and all case endings except the ablative.

Western group (Centum languages):

Greek (Hellenic) language(s)

Not much known about the possible substratum languages, spoken in Greece before

the arrival of Hellenic tribes. On Crete, traces were found of Minoan civilization

(Minos, legendary king of Crete) in the (yet to be deciphered) script Linear A. This

script was probably the basis for the Linear B, a script which was found in the Room

of the Chariot Tablets in Knossos, dating from 1450-1350 BC, in Mycenaean Greek.

Linear B was deciphered in 1957. Most inscriptions were found on the islands Crete

and Cyprus, but some also in the southern parts of the Peloponnese. The demise of

Mycenaean civilization – 1100 BC – was caused by Doric invasion. During the

subsequent Greek Dark Ages both literacy and the population dropped drastically.

Greek reappears in the alphabetic script in the 8th c. BC. It is called Archaic Greek.

Iliad, Odyssey and Homeric hymns to gods belong to this era. They were written in

the Ionic dialect (coast of Asia Minor, the islands of the Aegean Sea). Poetry was

composed in a mixture of ionic and Aeolic (Lesbos, Thessaly, Boeotia - Thebes)

dialects.

Classical Greek, from 480 BC on; Attic, the dialect of Athens (Attic-Ionic dialect), was

the language of Sophocles, Euripides, Plato, Aristotle, Pindar and Sappho wrote in

Doric.

Around the 5th century, Attic was accepted as the official language of the Macedon

court. It became the official language over an enormous area in the eastern

Mediterranean – from Italy, to Egypt, to Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

Its simplified variety is called Hellenic Greek – Koine.

hē koinē diálektos ‘the common language’

In contrast to classical Greek, Koine shows a reduction of vowels, e. g. ei, ē, i > [i]; ai,

e > [ɛ], oi, u [y]; aspirated stops ph, th, kh became [f, θ, x], voiced stops became

fricatives b, d, g [v, ð, ɤ]; dual, optative mood lost, distinction between perfect and

aorist lost.

Purist reaction – Byzantine Greek, artificially archaized classical Greek.

Modern Greek is descended from Koine. In 1828 it got its ‘purified’ standard

Katharevusa, the spoken standard is Demotic. In 1976 Demotic replaced

Katharevusa as the written standard.

Italic languages

Italic tribes had settled the Apennine peninsula probably by 1000 BC. Of all their

languages, divided into Latino-Falascian and Osco-Umbrian (Sabellic) groups, only

Latin survived.

The first inscriptions in Archaic Latin date from 7th BC – mid 2nd BC.

Classical Latin – golden and silver ages (150 BC – AD 180 – death of Ovid AD 17,

death of Marcus Aurelius 180)

Vulgar Latin was the spoken variety of Latin, the one which underwent many

changes especially when used in the faraway provinces of the Roman Empire.

Unstressed vowels were syncopated, vowels coalesced, velars were palatalized

before front vowels, the number of cases was reduced (ad regem instead of regī),

periphrastic verbal constructions replaced synthetic tenses – compound perfect

tenses with habēre: ego habeō cantātum, compound future cantāre habeō

It was from Vulgar Latin that Romance languages evolved: Portuguese, Spanish,

Catalan, Ladino, French, Occitan (Provencal), Italian, Romanian, Rhaeto-Romance

(Ladin, Friulian, Romansch)

Celtic languages:

Celtic culture in Europe is associated with the Hallstatt culture (late Bronze, early Iron

Age). Between 1200 and 500 BC their territory stretched from central Europe to

British Isles, to Asia Minor.

Celtic languages preserved almost all Indo-European grammatical features, but had

V-S-O word. They are traditionally divided into Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic.

Linguists, however, distinguish between the Q-Celtic and P-Celtic languages,

according to the respective development of IE labiovelars.

Little is known about continental Celtic languages, except for the relatively modest

traces of Gaulish in French.

Insular Celtic languages were all affected by the initial consonant mutation. Both

groups are respresented:

Gaelic, Goidelic (Q-celtic – labiovelars into velars): Irish, Scottish, Manx

Brythonic (P-celtic, labio-velars into labials): Welsh, Cornish, Pictish, Breton

Germanic languages:

Name probably after a tribe called Germānī in Latin. The older term Teutonī,

Teutonēs, came from another tribal name. Common Germanic or Proto Germanic

was probably spoken in the north of Europe, in southern Scandinavia, along the

coasts of the North and the Baltic seas, in the first half of the first millennium BC. The

Roman historian Tacitus wrote a monograph on Germanic people and their culture

(AD 98). Germanic tribes must have had contacts with Balto-Slavic and Finnic

people, which is manifested in loanwords and certain common linguistic features.

Traditionally, Germanic languages are divided into three groups: East Germanic,

North Germanic and West Germanic languages.

East Germanic:

East Germanic languages are all extinct. They evolved from dialects spoken along

the rivers Vistula and Oder. The most important East Germanic language is Gothic.

Goths must have lived in the Vistula area until the 3 rd century and then they migrated

towards the Black Sea. A century later, they are already divided into two

communities. The eastern branch – Ostrogoths lived east of the river Dniester,

Visigoths (“good” Goths, western Goths) between the Dniester and the Danube.

When Huns started to attack from the east, Ostrogoths succumbed and many joined

Attila in his raids in Gaulle. When Huns got defeated, Ostrogoths reclaimed their

independence and were granted permission to settle in Pannonia. In 488 their king

Theodoric conquered Italy and effectively ruled over the entire Western Roman

Empire, even though he never claimed the title of the emperor. Ostrogoths got

assimilated with the local population. Their rule was broken by Byzantium in 555.

Visigoths found sanctuary against the Huns in Byzantium, south of the river Danube.

They had a pact with emperor Theodosius to serve as soldiers in his army. After the

death of Theodosius in 395, Visigoths rebelled, attacked Greece under Alaric I and in

410 even ransacked Rome. Alaric’s successor Ataulf led them to the west. Their

kingdom in Spain survived until 711, when they were defeated by Arabs.

Goths were converted to Christianity early on. Bishop Wulfila, Ulfila ‘little wolf’ (311382) devised a special alphabet based on Greek uncials, and translated the Bible

into Gothic. Copies of the Bible from the 6th century have been preserved and they

provide the best insight into the structure and nature of the early Germanic

language(s). Gothic itself survived longest in the Crimean area (Crimean Gothic), but

became extinct in the 18th century.

Other East Germanic languages – Vandalic, Burgundian, Rugian, Gepidian – had

become extinct by the 10th century.

North Germanic:

North Germanic languages evolved from Germanic dialects which were spoken on

the territory of Scandinavia. They were first recorded as runic inscriptions in a

language called Old Norse, from the 3rd century. Around the year 800, Nordic was

already divided into eastern and western Norse. Easter Norse evolved into Old

Swedish and Old Danish, western into Old Norwegian. Between the 9 th and the 11th

c., Vikings took their Norwegian dialects to Faroese islands and to Iceland, where

they eventually evolved into Faroese and Icelandic.

Norway came under the Danish rule towards the end of the 14 th century and Danish

became the official language in Norway. Southern Norwegian dialects were strongly

affected by Danish, and together they gave rise to a language called Dansk-Norsk or

Riksmål. This language survives in modern Bokmål, one of the two official languages

in Norway. When Norway became independent in 1814, Ivar Aasen tried to boost the

national identity by creating a new, language on the basis of Danish-free northern

and western dialects. This new official language is called Nynorsk. It is spoken by

about 20% of the population.

Literary tradition of North Germanic languages is best represented in Icelandic.

Sagas and the two Eddas recount the exploits of legendary Norse heroes and king.

They were written down mostly between the 12th and 14th centuries.

West Germanic languages evolved from dialects that were spoken by Germanic

tribes along the rivers Elbe, Rhine, Vesser, and on the coasts of the North Sea.

The North Sea dialects evolved into Ingvaeonic languages: Old Frisian, Old English

and Old Saxon. Old Frisian is the languages closest to Old English and many believe

in their common Anglo-Frisian ancestor. Old English evolved from the dialects of

Saxons, Angles and Jutes, who settled in England in the 5 th century. Saxony was an

independent duchy from the 8th century until the end of the Middle Ages and Saxon

had a rich literary production during 800-1000 and 1200-1300. Today it survives as a

special Low German dialect, Plattdeutsch.

Germanic tribes by the Elbe spoke Langobardic, Bavarian and Alemannic dialects.

Langobardic became extinct; Bavarian is preserved in modern Bavarian and Austrian

dialects, Alemannic as Swiss German. Bavarian and Alemannic are known as Upper

German (Oberdeutsch). Together with Lower Franconian they evolved into Old High

German, the direct predecessor of modern standard German.

Franks, who lived by the rivers Rhine and Weser, spoke Frankish. One group of

Frankish dialects, High Franconian, was affected, along with the Upper German, by

the Second or High German consonant shift. Low Franconian evolved into Dutch with

Afrikaans and Flemish. Frankish dialects are preserved also in Luxembourgish.

Yiddish evolved from a Middle High German dialect, spoken by Jews in Germany in

the 9th and 10th centuries. It is a creolized variety of German, written in an adapted

Hebrew script. It has many Hebrew words, as well as Slavic, which it adopted after

Jews had moved to eastern Europe.

LINGUISTIC FEATURES OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES

Germanic languages belong to the Centum group of Indo-European languages. In

phonology, they are distinguished from other IE languages by the effects of

Grimm’s Law

Verner’s Law

development of *u before syllabic sonorants

coalescence of IE short *a, *schwa and *o into *a, and long *ā and *ō into *ō

fixation of word accent on the first syllable.

GRIMM’S LAW

Grimm’s Law or the First Proto-Germanic Consonant shift is a series of sound

changes which Johann Jacob Grimm described in his Deutsche Grammatik in 1822.

These changes affected Indo-European stops (plosives) in the following manner:

1) Indo-European voiceless stops became fricatives in Proto-Germanic;

2) Indo-European voiced stops became voiceless stops in Proto-Germanic;

3) Indo-European voices aspirated stops became voiced fricatives in ProtoGermanic, and subsequently voiced stops in many positions.

Examples:

(1)

PIE *p > Germ *ɸ > f

PIE *penkwe > Germ. *ɸemɸe > OE fīf > five; OHG finf, ON fimm; Slov. pet

Also: foot – pied, pedal; field – polje; free – prijati; friend – prijatelj; foam – pena;

father- pater.

PIE *t > Germ *þ

PIE *tr̥n- > Germ. *þurn- > OE þorn > thorn; HG. Dorn; Slov. trn

Also: thin – tanek, toča-thunder, tri-three, terra (dry land) – thirst

PIE *k̑ > Germ. *x

PIE * k̑erd- > *xert- > OE heorte > heart; HG Herz, Slov. (sr(d)ce, sredina,

Also: (h)loud – slovo, sto-hundred, haulm - slama

PIE *k > Germ. *x

PIE *kroṷos > Germ. *xraṷas > OE hrēaw > raw; Slov. krvav

Also: hew – kovati, Srb. Kosa – ang. Hards (coarse fibers of flax and hemp)

PIE *kw > Germ. Xw

PIE *kwo-, > Germ. *xwaz- > who; HG (h)wer, L. quid, quod, Slov. kdo

Also: while - po-koj (while related to quiet)

(2)

PIE *b > Germ *p

PIE *slēb-, *slōb- > Germ.*slē1p- > OE slǣpan > sleep; Slov. slab

Also: pool – blato, lip – labia, deep – dubok

PIE *d > Germ. *t

PIE *deru-, *doru- > Germ. *treṷ- OE trēo > tree: Slov. drevo, drva

Also: two – dva, duo, ten – deset, timber –dom; ped- foot

PIE *ĝ > Ger. *k

PIE *ĝr̥n- > Germ. *kurn- > OE. corn > corn; L. granum, Slov. zrno

Also knee - L. genū, know – Gr. Gnōtós, znati

PIE *g > Germ. *k

PIE *gel-; *gol- > Germ. *kald-az > OE cold > cold; Slov. hlad, L. gelu ‘frost’

Also: yoke – igo, joga; carve – Gr. Gráphein

PIE *gw > Germ. *kw

PIE *gwen- > OE cwēn > queen; Slov. žena ; Gr. Gunē;

Aslo: quick – živ

(3)

PIE *bh > Germ. * β > *b (by the end of Germ. Period, initially and after nasals)

PIE *bhrāter > Germ. *brōþar > brother; Slov. brat

Also: bear – brati, be – biti

PIE *dh > Germ. *ð > *d

PIE *dhur- ; dhṷer- > Germ. *dur- > OE duru > door, Slov. duri, dver

Also: do – deti, mead – med, rdeč – red;

PIE *ĝh > Germ. * γ > * g

PIE *ṷeĝh- > Germ. * weǥ- > OE weg > way; Slov. voz

PIE *gh > Germ * γ > g

PIE *mogh-, megh > germ *maǥ- OE mæg > may; Slov. mogel

Also: lay – legel, gos - goose

PIE *gwh > germ. *ǥw

PIE *gwher- > Germ. Warm- > OE wearm > warm; Slov. goreti

Also: snow - sneg

Exceptions:

Voiceless stops did not change to fricatives after s (stand).

In cluster of 2 stops – only the first one affected (oktou > aht).

VERNER’S LAW

-

Described in 1876 by the Danish linguist Karl Verner, Verner' Law explains the

“exceptions” to Grimm’s Law, i. e. the emergence of voiced fricatives where

one would expect voiceless ones. This change must have happened later than

Grimm’s Law, since all voiceless fricatives were affected, the IE *s, as well as

those that emerged as the consequence of Grimm’s Law.

Germanic voiceless fricatives *s, *f, *þ, *x, *xw became voiced medially if not

preceded by an accented syllable.

IE *upéri > Germ. *uferi > *uβeri > NE. over

IE *kasón > Germ. *xason > xazon > NE. hare (in West Germanic languages)

SYLLABIC RESONANTS

Indo-European syllabic resonant developed * u before them in Proto-Germanic:

IE. *l, *r, *m, *n > Germ. *ul, *ur, *um, *un

PIE *ghlt̥om > Ger. *ǥulþam > NE. gold (zlato)

PIE *tr̥n- Germ. þurn- > NE. thorn ; trn; murder-mrtev

VOWELS

The following groups of Indo-European vowels have been reconstructed:

a) short monophthongs: *a, *e, *i, o*, *u, *ə (schwa)

b) long monophthongs: *ā, *ē, *ī, *ō, *ū

c) short diphthongs: *ai, *ei, *oi, *au, *eu, *ou,

d) long diphthongs: * āi, *ēi, *ōi, *āu, *ēu, *ōu

Proto-Germanic development:

a) IE short *a, short *o and *ə (schwa) merged into Germ. *a

b) IE long *ā and *ō merged into Germ. *ō

c) IE long *ē remained in Proto Germanic, but is notated as *ē1. A new long *ē2

appeared of uncertain origin, which was higher than *ē1.

d) In many positions, especially before nasals, IE short *e changed to *i.

e) IE diphthong *ei changed to Germ. long *ī

f) IE *ai and *oi merged into Germ. *ai

g) IE *au and *ou merged into Germ. *au

Examples:

IE *a, *o, *ə > Germ. *a

IE *o k̑tōu > Germ.* axtōu (osem)

IE *ō, *ā > Germ. *ō

IE *bhrātēr > Germ. *brōþer

IE *e > *i (especially before nasals)

IE *wento- > Germ. *windaz

WEST GERMANIC

Three West Germanic languages were attested before 1000: Old English, Old Saxon

and Old High German. The first two must have been mutually intelligible.

The following changes are shared by all West Germanic languages:

1) Final *z was lost, otherwise rhoticized to r:

IE *was-, *wēs-‘ > Germ. *was, *wē1z-‘ > OE wæs, wǣron

2) All consonants except r were geminated if followed by *j and preceded by a short

vowel: Germ. *bidjan > OE biddan

3) Germanic voiced dental fricative *ð (from IE *dh) became a stop in all positions.

IE *pətḕr > Germ. *faþèr > *faðer > OE fæder

Vowels:

Germanic *ē1 became ā, but in Old English and Frisian it was later fronted to ǣ or

even ē.

All West Germanic languages were affected by mutations.

Palatal mutation, i-Umlaut

All vowels except e under the influence of i or j in the next syllable. The vowel thus

became more similar to i. So, for example, in Old English we find instead of

*a > æ, or even e before nasals

*o > e

*u > i

*eo > ie

*ea > ie.

The effects of this i-mutation are preserved in the conjugation of verbs (cf. 2 nd, 3rd

person singular in some German verbs), in the mutation plural of some nouns in

English (because of the Germanic plural suffix *iz), in some comparative/superlative

forms of adjectives (because of the suffixes *iza and *ista), and in some derivatives

(cf. English full and fill, long and length etc.)

Germ. *mūs, pl. *mūs-iz > OE mūs, pl. mȳs ‘mouse, mice’

Cf. also: old – elder, full – fill etc.

Back mutation, a-Umlaut

*i or *u were lowered under the influence of *a to *e or *o. It happened in late

Proto Germanic, common in OHG, rare in other Germanic languages.

Germ. *wiraz > OE wer

Germ. *gulþam (< IE*ghltom) > OE gold

(prevented by nasal: hund)

In INGVAEONIC1 languages (Old English, Old Saxon, Old Frisian) *n disappeared

before a fricative and that process resulted in the lengthening of the preceding vowel:

Vowel + nasal + fricative > long vowel + fricative

1

Ingvaeonic – the name comes from the tribal group Ingvaeones who lived by the North Sea.

Cf. German uns and OE ūs (unser, our); gans – goose; fimf – five

OLD ENGLISH and OLD FRISIAN (ANGLO-FRISIAN?) had two major changes in

common: the so-called “brightening” of long *ā (from *ē1) and of short *a, and the

smoothing of the Germanic diphthong *ai to long *ā.

In pre-literary time, Old English got new diphthongs. This was the result of

either BREAKING – FRACTURE (harmonic breaking) or the so-called backUmlaut.

1) Breaking:

pre-OE *e > eo

pre-OE *æ > ea before {r+C, l+C, h+C, h*#}

heorte, feallan,

2) Back-Umlaut

Short i, e, sometimes a > diphthong eo, io, ea when a back vowel occurred

in the next syllable, but only before one consonant (in WS labial f, b, w or

liquid r, l)

Seofon, heofon...

Old English velar consonants had been palatalized in palatal environment and

voiceless fricatives became voiced in voiced environment.

OE cinn [ʧin], scip [ʃip] (vs. cann, scōl)

OE giefan [jevan], gē [je:] (vs. gān, frogga)

The Lord’s Prayer in some Germanic languages

Gothic:

Atta unsar, þu in himinam,

weihnai namo þein,

qimai þiudinassus þeins,

wairþai wilja þeins,

swe in himina jah ana airþai.

Hlaif unsarana þana sinteinan gif uns himma daga,

jah aflet uns þatei skulans sijaima,

swaswe jah weis afletam þaim skulam unsaraim,

jah ni briggais uns in fraistubnjai,

ak lausei uns af þamma ubilin;

[unte þeina ist þiudangardi

jah mahts jah wulþus in aiwins.]

Swedish:

Vår fader, du som är i himlen.

Låt ditt namn bli helgat.

Låt ditt rike komma.

Låt din vilja ske,

på jorden så som i himlen.

Ge oss i dag vårt bröd för dagen som kommer.

Och förlåt oss våra skulder,

liksom vi har förlåtit dem som står i skuld till oss.

Och utsätt oss inte för prövning,

utan rädda oss från det onda.

German:

Vater Unser im Himmel,

Geheiligt werde Dein Name,

Dein Reich komme,

Dein Wille geschehe,

wie im Himmel so auf Erden.

Unser tägliches Brot gib uns heute.

Und vergib uns unsere Schuld,

wie auch wir vergeben

unseren Schuldigern.

Und führe uns nicht in Versuchung,

sondern erlöse uns von dem Bösen.

Denn Dein ist das Reich und die Kraftund die Herrlichkeit in Ewigkeit.

Dutch:

Onze Vader in de hemel,

uw naam worde geheiligd,

uw koninkrijk kome,

uw wil geschiede,

op aarde zoals in de hemel.

Geef ons heden ons dagelijks brood

en vergeef ons onze schulden

zoals ook wij anderen hun schulden hebben vergeven,

en stel ons niet op de proef

maar verlos ons van de duivel.

Old English:

Fæder ūre, þū þe eart on heofonum;

Sīe þīn nama gehālgod,

tō becume þīn rīce,

gewurþe þīn willa,

on eorðan swā swā on heofonum.

Urne gedæghwamlican hlāf sele ūs tōdæg,

and forgif ūs ūre gyltas,

swā swā wē forgifaþ ūrum gyltendum,

and ne gelǣd þū ūs on costnunge,

ac āls ūs of yfele, sōþlīce.

Modern English:

Our Father,

who art in heaven,

hallowed be thy name;

thy kingdom come;

thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread;

and forgive us our trespasses

as we forgive those who trespass against us;

and lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil.

Tok Pisin

Papa bilong mipela

Yu stap long heven.

Nem bilong yu i mas i stap holi.

Kingdom bilong yu i mas i kam.

Strongim mipela long bihainim laik bilong yu long graun,

olsem ol i bihainim long heven.

Givim mipela kaikai inap long tude.

Pogivim rong bilong mipela,

olsem mipela i pogivim ol arapela i mekim rong long mipela.

Sambai long mipela long taim bilong traim.

Na rausim olgeta samting nogut long mipela.

Kingdom na strong na glori, em i bilong yu tasol oltaim oltaim.

Tru.

father

IE *pətēr

IE *p > Ger. *f – Grimm’s law, all voiceless plosives > fricatives

IE *ə > Ger. *a , IE ə, o, a > germ, a (independent change)

IE *t > Germ. *þ (Grimm’s law) > ð (Verner’s law – unaccented vowel precedes)

Germ. ð > d in all WG languages

Germ. a > OE æ (brightening of a and ā in Anglo-Frisian)

OE æ > ME a > NE [ɑ:] before voiceless fricatives and [ð]

ME <d> > <th> in 16th century.

goose

IE *ghans- > Germ. *gans- > OE gōs > NE [gu:s] goose

IE *gh > Germ. * [γ] > g (Grimm's Law)

Germ *-ans > Ingv. *ōs : In Ingvaeonic languages the nasal disappeared before

voiceless fricatives and the vowel preceding it became long. (Germ. long * ā became

*ō)

stone

IE *stoino- Germ *stain- > OE stān > NE [stəʊn] stone

IE *oi > Germ. *ai

Germ. *ai > OE, OFries. ā (smoothing of *ai)

cow

IE *g