CSHSE Self-study - College of HHD

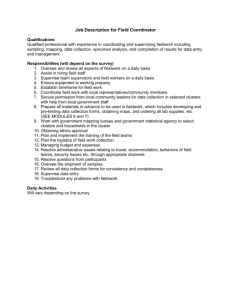

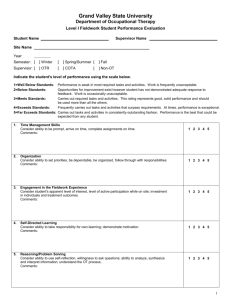

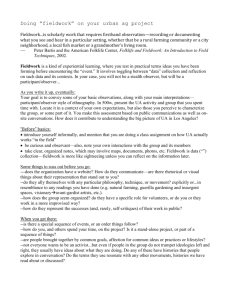

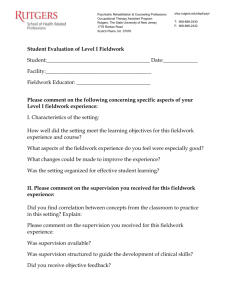

advertisement