By REBECCA SKLOOT, New York Times

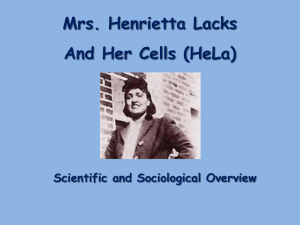

Cells That Save Lives Are a Mother's Legacy

By REBECCA SKLOOT, New York Times

Deborah Lacks closed her eyes as a young cancer researcher opened the door of his floorto-ceiling freezer. She stood clutching the ragged dictionary she uses to look up words like

''DNA,'' ''cell'' and ''immortality.'' When the icy breeze hit her face, she opened her eyes slowly, and stared into a freezer filled with tiny vials of red liquid. ''O God,'' she gasped, ''I can't believe all this is my mother.''

Fifty years ago, when Deborah Lacks was still in diapers, her 30-year-old mother, Henrietta

Lacks, lay in a segregated ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. The resident gynecologist sewed radium to her cervix in an attempt to knock out the cancer that was killing her. But before he finished, and without telling her, he took a small sample of her tumor and sent it downstairs to Dr. George Gey (pronounced guy), head of tissue culture research at Hopkins. Dr. Gey had spent almost 30 years collecting cancerous human cells and trying to make them grow, but until Ms. Lacks came along, they never did. Though

Henrietta died a few months after her radium treatments, her cells are still living today.

Henrietta's cells -- named HeLa after the first letters in Henrietta and Lacks -- became the first human cells to live indefinitely outside the body. They helped eradicate polio, flew in early space shuttle missions and sat in nuclear test sites around the world. In the 50's, HeLa cells helped researchers understand the differences between cancerous and normal cells, and quickly became a standard laboratory tool for studying the effects of radiation, growing viruses and testing medications. HeLa is still one of the most widely used cell lines; in fact, this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for research in which HeLa cells played a pivotal role.

Yet it was not until nearly two decades later -- just before magazines like Jet and Emerge started writing stories about a black family whose mother had made important contributions to science without their knowledge -- that anyone in Ms.

Lacks's family knew what had happened. Ms. Lacks, 52, doesn't remember how she heard, but she'll never forget her reaction: ''I went into shock,'' she said. ''Why didn't they just ask if they could use her cells?''

If the issue of using patient tissue without permission wasn't a pressing one in the 50's, informed consent has certainly become a heated topic today.

''In 1951, they wouldn't have felt like they needed to ask,'' said Ruth Faden, executive director of the Johns Hopkins

Bioethics Institute. ''It's a sad commentary on how the biomedical research community thought about research in the

50's, but it was not at all uncommon for physicians to conduct research on patients without their knowledge or consent.''

Today, when patients go in for surgery, they're usually asked to sign a form saying whether their tissues can be used for research. But, said Lori Andrews, a professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law and co-author of ''Body Bazaar: The Market for Human Tissue in the Biotechnology Age,'' that practice doesn't solve an important problem.

''All of us have blood or tissue on file somewhere,'' Ms. Andrews said. ''Today, every drop of blood taken from people, every organ or biopsy removed by a surgeon, is in the pipeline toward research and commercialization. Since the 60's, every newborn in the U.S. has been tested for genetic disorders, and many of their samples are still on file for use in later research. There are no rules governing who has access to these samples.''

Some bioethicists and lawyers want legislation requiring researchers to obtain consent before conducting research on any tissues, including those already in storage. But many research organizations -- the American Society for Investigative

Pathology, for example, and the College of American Pathologists -- have argued that such blanket legislation could seriously damage scientific progress.

Dr. Mark Sobel, senior executive officer of the American Society for Investigative Pathology, agrees that informed consent should be required before new tissues are collected. But to Dr. Sobel, the millions of tissue samples collected before the current shift toward informed consent, like Henrietta Lacks's cells, are a special case. Scientists conducting research on those samples have no way to contact the donors for permission.

''This is where we want some flexibility,'' Dr. Sobel said. ''We want recognition that there's a way -- with policies in place for confidentiality and protecting the patients -- that you can still use these very important resources of human tissue.

Otherwise, it's going to impede medical research.''

To Dr. Sobel, using these samples ethically means protecting patient identity and assuring complete anonymity. Dr. Gey tried to do this for Ms. Lacks, but rumors began circulating that HeLa stood for someone named Helen Lane. When a few colleagues of Dr. Gey, who has since died, tried to correct this error, the Lacks family was thrown into a world of science they didn't understand.

Ever since Deborah Lacks first heard about her mother's cells, she has been trying to understand how they could be alive decades after her death. So she got a notebook, a dictionary and a science book and began teaching herself about cells, one word at a time.

''A cell,'' she wrote, ''is a minute portion of living substance.'' She copied one definition after another. ''As long as the cell receives an adequate supply of food,'' she wrote, ''it will continue to grow and thrive for the duration of its life cycle.''

Not even Dr. Gey ever understood precisely why the life cycle of Ms. Lacks's cancer cells has continued indefinitely.

Within a few years of learning about HeLa cells, the Lacks family began getting letters from researchers, asking them to donate blood so scientists could find genetic markers to help identify Henrietta's cells. But Ms. Lacks remembers differently: ''It was a typed letter, stating we need samples of the Lacks family to check her blood cells with theirs, to see if anybody has the same thing that she had,'' she said. Ms. Lacks was in her late 20's and had always worried that she might die at 31, just like her mother.

''I cried and cried,'' she recalled. ''I had my two children, they was babies at the time, and I said 'O God, am I going to make it past 31?' '' She dodged the researchers at first, because she didn't want to know whether she had cancer. When she finally decided to take the tests, she thought she'd get a phone call telling her whether she was going to live or die. She never heard back from the researchers and soon had the first of what would become several breakdowns.

Ms. Faden said: ''This could have been a very innocent misunderstanding.

But this is why researchers have to be as straightforward as possible, because the expectation is that when a doctor wants to do something to you, it's for your benefit. Physician-researchers need to make this clear by saying, 'I'm not doing this to help you, I'm doing it to advance science.' ''

Bobbette Lacks, Henrietta Lacks's daughter-in-law, says that if researchers had told them about HeLa cells, then informed them of future research, her family would have cooperated. But not now. ''I would never subject my kids to that,'' Bobbette Lacks said.

Until Ms. Lacks looked into that freezer filled with vials earlier this year, she had only read about her mother's cells; she had never seen them. Christoph Lengauer, the young cancer researcher who was showing her around his lab at John

Hopkins Oncology Center, leaned over a microscope, focused it on a single HeLa cell and projected it onto a monitor. She stared in silence, eyes wide, then sighed.

1.

How does Deborah Lacks feel at the end of the article?

2.

Should people retain rights to tissue samples after they are removed?

Substantiate your answers with reasoning and/or evidence.