Accountability: a tale of responsibility and attribution?

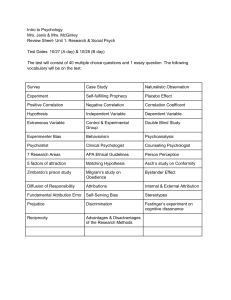

advertisement