Sample Student Essay - SCF Faculty Site Homepage

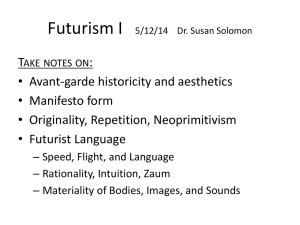

advertisement

Irina Zaremba Professor Jane Anderson Jones Intercultural Humanities III April 9, 2013 The Cyclist Futurism is the most important Italian avant-garde art movement of the 20th century. It celebrated advanced technology and urban modernity. Committed to the new, its members wished to destroy older forms of culture and to demonstrate the beauty of modern life – the beauty of the machine, speed, violence and change (The Art). They upset the old order not just with their paintings and sculptures, but also with poetry, music, manifestos, cabarets and confrontational happenings. Natalia Goncharova was the first woman and the first avant-garde artist to have a retrospective in a Moscow gallery – and she was only 32 at the time. Goncharova was heavily influenced by Futurists and the characteristics defining Futurism are seen in her art. She became famous in Russia for her Futurist work such as The Cyclist. On February 20th, 1909, Futurism began its transformation of Italian culture. The publication of the Futurist Manifesto, authored by writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, appeared on the front page of Le Figaro, which was the largest circulating newspaper in France (The Art). Marinetti stated: We want to fight ferociously against the fanatical, unconscious and snobbish religion of the past, which is nourished by the evil influence of museums. We rebel against the supine admiration of old canvases, old statues and old objects, and against the enthusiasm for all that is worm-eaten, dirty and corroded by time, we believe that the common contempt for everything young, new and palpitating with life is unjust and criminal. The stunt signaled the movement’s desire to employ modern, popular means of communication to spread its ideas. The Futurists were fascinated by the problems of representing modern experience, and strived to have their paintings evoke all kinds of sensations, and not merely those visible to the eye (The Art). Russian Futurism was a movement that was definitely influenced by Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto (Russian Futurism). Like their Italian counterparts, the Russian Futurists were fascinated with urban life and all that it represented. The technology was an important influence on their approach to show movement in painting, encouraging an abstract art with rhythmic, energetic qualities. They wanted the art to bring to mind the noise, heat, and even the smell of metropolis. When Marinetti, the leader of the Futurists, visited Moscow in 1914 to spread the word, Goncharova was not impressed. She even accused him of despising women. Her paintings, on the other hand, proved that she was already sunk in. She suggests motion in her painting The Cyclist (1913) by repeating the outline of the cycling man (Kent). The descriptive label of The Museum of Kinetic Form does a wonderful job describing the painting depicting a cyclist in motion. Many aspects of this painting show motion. One of these is the vibrating motion of the bicycle as well as the rider, which gives the impression that the cyclist is actually riding the bike. Another aspect of the painting that creates motion is the dust cloud that is being made by the cyclist. The swirling dust around the cyclist depicts the cyclist is going very fast (The Museum). The Cyclist captures the energy by emphatically dramatizing the lines and angular movements, which is why it is regarded as one of the archetypal works of Futurist painting. It embodies typical features of Futurism such as constant repetition, dislocation of the contours of the figure, which seems to be recorded in temporal and spatial sequence, and of fragments of street signs, in order to convey the bustle, noise, and movement of the city (The Russian Museum). The composition of the painting is, however, horizontally and vertically balanced and assiduously regulated, thereby distinguishing it from the classical works of Futurism. Natalia Goncharova was more than just a major artist of the avant-garde – she was also a controversial, unique, and highly visible personality in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Her antics drew both praise and derision. Together with the Russian Futurists, she was innovative and bold not only on canvas, but she also brought art into their daily life (Rogers). Goncharova shocked people by cross-dressing, wearing gowns revealing her painted breasts, and by parading around town with offensive remarks and images resembling tattoos. Those were just some of the actions that caused political figures to denounce Modernism as unwholesome and immoral (Kent). By her actions and her art work, Goncharova had definitely proven to be a modern artist. Modernist art was all about fragmentation versus order, the abstract and the symbolic Modernism). Her painting The Cyclist was influenced by Futurism, which was part of the general trend of Modernist rationalization of disruption. Even though Goncharova became an overnight sensation with the exhibition of her art, some of her work was greatly rejected by the critics. Her Pillars of Salt painting was seized by the police, and she was tried for producing pornography. Likewise, Evangelists, was taken by the police and banned by the Censorship Committee; Goncharova was denounced as a blasphemous counterpart of Antichrist (Kent). Fascinated with the dynamism, speed, and restlessness of modern machines and urban life, Futurists purposefully sought to arouse controversy and gain publicity by rejecting the still art of the past. Goncharova became a role model and a living proof that it was possible to be taken seriously as a female painter. Goncharova advised other women, “Believe in yourself more, in your strengths and rights before mankind and God. There are no limits to the human will and mind” (Kent). Because of her example, female artists during and after the Russian revolution, seized the opportunities offered by a unique moment in history. The political upheaval gave them the chance for the first time to work alongside men as their equals, developing new art appropriate for the new society. Even though Modernism was a controversial movement, it affected every aspect of life for not only the artists, but the people around them also. Works Cited Kent, Sarah. “Women of Futurists.” 2009. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Web. 6 Apr. 2013 <http://telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art_fetures/5549675/women-of-the-futurists.html>. “Modernism.” 2013. Wikipedia. Web. 6 Apr. 2013 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/modernism>. Rogers, Elizabeth. “Artists.” 2012. Art in Russian: Natalia Goncharova. Web. 2012. 8 April. 2013 <http://artinrussia.org/natalia-goncharova/>. “Russian Futurism.” 2013. Wikipedia. Web. 6 Apr. 2013 <http:en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_Futurism>. The Art Story Contributors. “Futurism.” 2012. The Art Story Foundation. Web. 9 Apr. 2013 <http://www.theartstory.org/movement-futurism.htm>. The Museum of Kinetic Form. Descriptive Label. Cyclist by Natalia Goncharova. 6 Apr. 2013 <https:sites.google.com/site/museumofkineticformsmokf/cyclist>. The Russian Museum: The Virtual Branch. Descriptive Label. Cyclist by Natalia Goncharova. 6 Apr. 2013 <http://www.virtualrm.spb.ru/en/resources/galleries_en/avant_garde/goncharova>.