Remembering the Nazis in Skokie Geoffrey R. Stone Sunday

advertisement

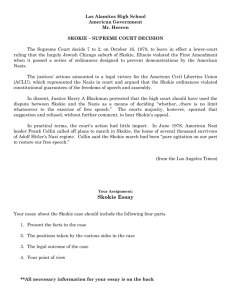

Remembering the Nazis in Skokie Geoffrey R. Stone Sunday morning marked the official opening of the Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, Illinois. This striking new institution is dedicated to "preserving the legacy of the Holocaust by honoring the memories of those who were lost and by teaching universal lessons that combat hatred, prejudice and indifference." The seeds of the Skokie Holocaust Museum were sown more than thirty years ago, when roughly thirty members of the Nazi Party of America sought to march in Skokie. The plan was for the marchers to wear uniforms reminiscent of those worn by the members of Hitler's Nazi Party, including swastika armbands, and to carry a party banner bearing a large swastika. At the time of the proposed march in 1977, Skokie, a northern Chicago suburb, had a population of about 70,000 persons, 40,000 of whom were Jewish. Approximately 5,000 of the Jewish residents were survivors of the Holocaust. The residents of Skokie responded with shock and outrage. They sought a court order enjoining the march on the grounds that it would "incite or promote hatred against persons of Jewish faith or ancestry," that is was a "deliberate and willful attempt" to inflict severe emotional harm on the Jewish population in Skokie (and especially on the survivors of the Holocaust), and that it would incite an "uncontrollably" violent response and lead to serious "bloodshed." The Skokie controversy triggered one of those rare but remarkable moments in American history when citizens throughout the nation vigorously debated the meaning of the United States Constitution. The arguments were often fierce, heartfelt and painful. The American Civil Liberties Union, despite severe criticism and withdrawal of support by many its strongest supporters, represented the First Amendment rights of the Nazi. As a young law professor at the University of Chicago, I had the played a minor role in assisting the ACLU. In the end, the Illinois Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals, and the United States Supreme Court contributed to the conclusion that Skokie could not enjoin the Nazis from marching. It is useful to consider the three primary arguments set forth by Skokie in support of its effort to forbid the march. First, the village argued that the display of the swastika promoted "hatred against persons of Jewish faith or ancestry" and that speech that promotes racial or religious hatred is unprotected by the First Amendment. The courts rightly rejected this argument, not on the ground that the swastika doesn't promote religious hatred, but on the ground that that is not a reason for suppressing speech. After all, if the Nazis could be prohibited from marching in Skokie because the swastika incites religious hatred, then presumably they couldn't march anywhere for the same reason, and movies could not show the swastika, and even documentaries could not show the swastika. And if the swastika can be banned on this basis, then what other symbols or ideas can be suppressed for similar reasons. What about movies showing members of the Ku Klux Klan? News accounts showing Palestinians committing suicide bombings in Israel or showing Israelis attacking civilians? Second, the village argued that the purpose of the marches was to inflict emotional harm on the Jewish residents of Skokie and, especially, on the survivors. Certainly, some residents would be deeply offended, shocked and terrified to see Nazis marching through the streets of Skokie. But they might also be offended, shocked and terrified to know 1 that Schindler's List was playing at a movie theatre in Skokie, or in Chicago, or in Illinois, and African-Americans might be offended, shocked and terrified to know that the movie Birth of a Nation was playing in a theatre in their town or nation. And so on. Moreover, it is doubtful that the actual intent of the Nazis was to inflict emotional harm on the residents of Skokie. Initially, the Nazis sought to march in a totally different community in Chicago, one with almost no Jewish population. But they were denied a permit. They then decided to march in Skokie in order to get publicity for their grievance. Indeed, the signs they planned to carry in Skokie did not say "Bring Back the Holocaust," but "White Free Speech" and "Free Speech for the White Man." Making First Amendment rights turn on judgments about a speaker's subjective intent is a dangerous business, because intent is very elusive and police, prosecutors and jurors are very prone to attribute evil intentions to those whose views they despise. Third, the village argued that if the Nazis were permitted to march there would be uncontrollable violence. But is this a reason to suppress speech? Isn't the obligation of the government to protect the speaker and to control and punish the lawbreakers, rather than to invite those who would silence the speech to use threats of violence to achieve their ends? If the village of Skokie had won on this point, then southern communities who wanted to prosecute civil rights marchers in Selma, Montgomery and Birmingham could equally do so, on the plea that such demonstrations would trigger "uncontrollable violence." Moreover, once government gives in to such threats of violence it effectively invites a "heckler's veto," empowering any group of people who want to silence others to do so simply by threatening to violate the law. The outcome of the Skokie controversy was one of the truly great victories for the First Amendment in American history. It proved that the rule of law must and can prevail. Because of our profound commitment to the principle of free expression even in the excruciatingly painful circumstances of Skokie more than thirty years ago, we remain today the international symbol of free speech. (Ultimately, a deal was worked out and the Nazis agreed to march in Chicago rather than in Skokie.) Ironically, but exquisitely, it was the Skokie controversy that caused the survivors in Skokie and around the world to recognize that, in the words of the new Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, "despite their desire to leave the past behind, they could no longer remain silent." It was in the wake of the Skokie affair that "Chicagoarea survivors joined together to form the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois." As a result on this controversy, the survivors dedicated themselves to "combating hate with education." And so now, with only a handful of survivors still alive to see the moment, we now have this extraordinary memorial and museum. As Justice Louis Brandeis once explained, the Framers of our First Amendment knew "that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones." The opening today of the Holocaust Museum and Education Center proves the profound wisdom of the principle that "the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones." Huffington Post, 19/4/2009 2