manuscript (1)

advertisement

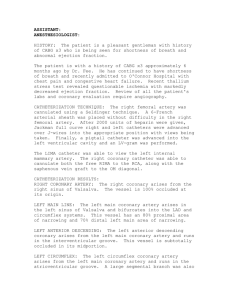

Tas CAN LAD OCCLUSION RESTORE LIMA GRAFT FLOW? Running Title: Competetive Flow Between LAD and LIMA Assist. Prof. M. Hakan Tas, M.D.1, Assist. Prof. Ziya Simsek, M.D.1, Dr.Husnu Degirmenci, M.D.1, Assist. Dr. Lutfu Askin , M.D.1, Assoc. Prof. Ednan Bayram, M.D1, Prof. Huseyin Senocak, M.D 1 . 1 Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, Ataturk University, Erzurum, Turkey Address for correspondence: Assist.Prof.Dr.M. Hakan Tas Atatürk University Cardiology Department 25240-Erzurum/TURKEY Telephone: +90-532-6856848 Fax number: +904422352384 E-mail: mhakantas@gmail.com Tas Abstract Competetive flow is the major reason for failure of Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG). Physiological effects and etiological causes of coronary competetive flow are still certainly unknown. But in noncritical coronary lesions it is more frequently and on higher rates. For this reason if you are deciding for CABG it is important to evaluate coronary lesions correctly for prevention of coronary competetive flow. This case report introduces clinically improved coronary arterial disease after turning of competetive flow to graft artery by worsening stenosis of native coronary artery. Keywords: Angiography, Competetive flow, Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Tas Introduction Competetive flow is defined as competetion of native arteries and grafts for distal perfusion after Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting ( CABG ) operation. 1 Cause of this phenomenon is certanly unknown however it is affected by the degree of stenosis on diseased vessel, kind of the graft, diameter of graft vessel and anastomosed diseased vessel, injury of graft and technical inaccuracies .2 In this report we want to acquire a case for literature which is clinically improved coronary arterial disease after turning of competetive flow to graft artery by worsening the stenosis of native coronary artery. Case 63 years old male applied to our policlinic with typical chest pain. In his medical history after an inferior myocardial infarction and a stent was implanted to right coronary artery (RCA) 2 years ago. 1 years ago patient underwent surgical revascularisation involving left internal mammarian artery (LIMA) graft on left anterior descending artery (LAD) and a venous graft on RCA. Patient has got diabetes mellitus and hypertension. We found pathologic Q vawes on ECG. Cardiac markers were normal. Patient admitted to our cardiology clinic. Despite medications patient’s chest pain continued. Patient has undergone coronary angiography. Native RCA was 90% stenosed but venous graft was patent. 70% stenosis in proximal LAD on cranial position founded. There was no flow in LIMA graft (Figure 1A). A stent was implanted to LAD and TIMI 3 flow restored (Figure 1B). Patient discharged from hospital with medications. Five months later patient applied to our policlinic with exercise induced angina. We learned that patient did not take his drugs regularly. And a new coronary angiography performed. 90% instent restenosis founded in LAD (Figure 1C). But LIMA-LAD bypass was seen patent (Figure 2A-B). We thought that current situation Tas originated from the competetive flow between LIMA graft and native LAD. Patient’s medical treatment arrenged again and discharged from the hospital. Discussion The main cause for insufficiency of coronary bypass grafts is the competetive flow with native coronary arteries. Contributary factors for competetive flow are progression of atherosclerosis, intimal hyperplasia and technical deficiencies.3 However noncritical coronary arterial stenosis decreases wall shear stress of LIMA graft and anastomosis; in this wise competetive flow increases. Nowadays computational liquid dynamics is used for investigating the wall shear stress of bypass graft and native coronary arteries.4 Some studies showed relationship between stenosis of native coronary artery and the degree of competetive flow. Berger et al. reported that proximal coronary arterial stenosis is the major indicator of the LIMA graft occlusion.5 Pevni et al. reported that noncritical coronary arterial stenosis causes nonfunctioning grafts.6 Nordgaard et al. showed that high grade competetive flows could be originate from noncritical coronary lesions and partial competetive flows could be originate from critical coronary lesions. They did not see competetive flow in totally stenosed coronary arteries.2 A recently published animal study showed the predictive value for competetive flow of LIMA graft is the <75% stenosis of coronary arteries.7 In our case we thought that high grade competetive flow occured by the mistake of evaluating coronary lesions before bypass operation. In the light of existing studies we observed that the noncritical coronary lesions contribute competetive flow. Siebenmann et al. reported string phenomenon of the internal mammarian artery caused by 50% and less stenosis of grafted vessel.8 In our case we did not see string phenomenon because of competetive flow. This event can be attached to not enough time for development of endotelial dysfunction and partial competetive flow. Our case is instructive and remarkable Tas for bypass grafted noncritical lesions can cause competetive flow and it can worsen coronary arterial disease clinically. But our patient's coronary arterial disease improved and changed the flow LAD to LIMA. Conclusion: Decision for CABG should be given with multidisciplinary approach and competetive flow should always be considered. However, diameter mismatch of graft and artery and bypass grafting to mild lesions should be avoided. On controversial cases measuring flows of two vessels can be directive for avoiding competetive flow. References 1. Pagni S, Storey J, Ballen j, et al. Factors affecting internal mammary artery graft survival: how is competitive flow from a patent native coronary vessel a risk factor? J Surg Res 1997; 71(2):172-178. 2. Nordgaard H, Nordhaug D, Kirkeby-Garstad, Lovstakken L, Vitale N, Haaverstad R. Different graft flow patterns due to competitive flow or stenosis in the coronary anastomosis assessed by transit-time flowmetry in a porcine model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009; 36(1): 137-142. 3. Nwasokwa ON. Coronary artery bypass graft disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;123: 528 – 533. 4. Stone PH, Coskun AU, Kinlay S, Popma JJ, Sonka M, Wahle A et al . Regions of low endothelial shear stress are the sites where coronary plaque progresses and vascular remodelling occurs in humans: an in vivo serial study. Eur Heart J 2007;28:705 – 710. 5. Berger A, MacCarthy PA, Siebert U, Carlier S, Wijns W, Heyndrickx G et al. Longterm patency of internal mammary artery bypass grafts: relationship with preoperative severity of the native coronary artery stenosis. Circulation 2004;110:11-36. Tas 6. D. Pevni, I. Hertz, B. Medalion et al.’Angiographic evidence for reduced graft patency due to competitive flow in composite arterial grafts’’. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. vol. 133, no. 5, pp. 1220–1225, 2007. 7. Havard N, Abigail S, Dag N, et al. Impact of competitive flow on wall shear stress in coronary surgery: computational fluid dynamics of a LIMA-LAD model. Cardiovascular Research (2010) 88, 512-519. 8. Siebenmann R, Egloff L, Hirzel H, Rothlin M, Studer M, Tartini R. The internal mammary artery string phenomenon. Analysis of 10 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993; 7(5):235-8. Figure Legends Figure 1A: The angiographic view at the anterior-posterior position; there was no flow from LIMA graft to LAD. 1B: The angiographic view at the left caudal oblique position; there was TIMI 3 flow in LAD after stent implantation.1C: The angiographic view at the left caudal oblique position; there was a critical lesion in proximal LAD after stent restenosis. Figure 2A-B The angiographic views at the anterior-posterior position; LIMA graft flow restored after LAD occlusion Tas Figure 1A-B-C Figure 2A-B