File

advertisement

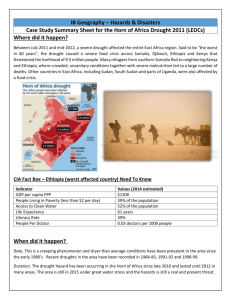

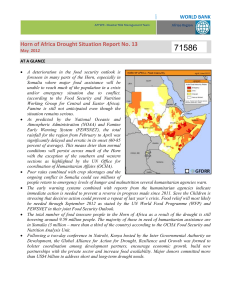

East African Drought: I wanted to explore more about what happened during the East African drought of 2011. What I found was surprising and horrifying all wrapped up in one terrible natural catastrophe. There was a drought affecting the entire Eastern Africa region threatening the livelihood of 10 million people. Between 50,000 and 100,000 people died, more than half of those children under five. It was the worst drought the area had seen for 60 years. It caused a severe food crisis across Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya. Sudan, South Sudan, and parts of Uganda were also affected. This catastrophe was triggered by a dry season. There are normally big rains from November-December, and again in the spring. However, in 2010 the rains ended in November, and December was hot and dry. The following primary season from April-June had less than 30% of average rain amount. This led to crop failure, and little grass for livestock resulting in widespread loss of livestock, and decreased milk production. Staple prices rose to record levels of up to 68% above the five year average, and livestock prices and wages fell. Prices increased up to 240% in Southern Somalia, 117% in South Eastern Ethiopia and 58% in Northern Kenya. Hundreds of dead livestock through the drought The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) anticipated the crisis in August 2010, but the warnings were not heeded. The conditions continued to worsen with failed rains. In January of 2011 the American ambassador to Kenya declared a disaster and called for urgent assistance. There was no full-scale response launched until July 2011 when malnutrition rates were far beyond emergency levels. On June 7, FEWS NET declared the crisis “the most severe food security emergency in the world today, and the current humanitarian response inadequate to prevent further deterioration.” By June 28, 12 million people in Eastern Africa were affected by the drought. Some areas were on the brink of famine, and many people were displaced in search of food and water. By July 20, the United Nations deglared famine in two regions of Southern Somalia, Lower Shabelle and Bakool. It was categorized a Phase 5 catastrophe/famine. Tens of thousands of people were believed to have died before famine was declared. Al-Shabaab, an al Qaeda linked islamic group, control most of southern Somalia hindering humanitarian operations. In early July, they let humanitarian organizations in to help, but by July 22, they had banned certain organizations from coming in. They feared the groups were acting as spies, or having a “political agenda, doing nothing like they were claiming.” He worried of volunteers coming to give aid in order to preach Christianity. Members of the group even intimidated, kidnapped and killed aid workers creating a partial suspension of humanitarian operations in southern Somalia. Map of food shortage in Eastern Africa by FEWS NET Failed rains, high food prices, and regional conflicts added up to a deadly combination in the entire Horn of Africa region. This is an unstable area, and through this disaster, even more violence and protests started. In Kenya, armed herders violently competed for dwindling resources resulting in over 100 herders killed. Thousands left their homes to seek food and shelter at refugee camps. Because of crowded, unsanitary conditions disease spread rapidly. Measels broke out in the Dadaab camps, Kenya and Ethiopia. 17,500 cases were reported in the first 6 months. 2 million children were at risk of getting the measles; 8.8 million were at risk for malaria, and 5 million for cholera. Malnutrition rates rose to astonishing levels, and widespread famine covered the entire Horn of Africa. 30% of children in Kenya and Ethiopia were suffering from acute malnutrition, with 50% in Somalia. More than two adults, or four children, were dying of hunger each day for every group of 10,000 people. Population as a whole had access to less than 2,100 kilocalories of food and four liters of water per day. 12 million people in the area needed food aid, 2.8 million in southern Somalia alone, which was the most affected area. By August 3, famine had been declared in Middle Shabelle, and the IDP settlements in Mogadushu and Afgoove. As well as parts of Kenya, which were affected by the drought conditions and wildfire outbreaks. There were food shortages in Northern and Eastern Uganda. In Mogadishu, heavy rains destroyed makeshift homes leaving thousands in southern Somalia displaced and left out in the cold. Thousands of people at a refugee camp By early September, the bay region of Somalia was added to the famine- stricken list. More than 920,000 refugees fled from Somalia to nearby countries, mostly to Kenya and Ethiopia. ¾ of Kenya was in dire need of food supplies, where malnutrition levels were the highest. 3.5 million Kenyans were at risk of malnutrition. 385,000 children and 90,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women were malnourished. Schools shut down because there was no food for the children. Kenya had 440,000 refugees in three camps. An estimated 1,500 refugees arrived each day, 80% of them women and children. Women and young girls also faced sexual violence in the camps, and on their travel to the camps. There was a high risk of them acquiring HIV/AIDS. It was a long, rigorous journey to travel to a refugee camp, taking many lives. Water shortage had a profound effect at the camps and infant mortality rates had tripled. Overall, 7.4 out of every 10,000 people died per day. Seven times higher than emergency levels of 1 out of 10,000 per day. A girl standing among the graves of 70 children on the outskirts of Dadaab. The long desert journey to relief camps has claimed many lives. The crisis was expected to worsen in following months, and large scale assistance was needed until December. In November, regions of Somalia were downgraded from famine to emergency levels. And December brought an improvement in malnutrition and mortality rates, through rainfall, good crops, and more opportunities for work. Crisis and stressed levels continued early into 2012, and the effects were still eminent. Aid had been shifted to recovery efforts, including digging irrigation canals and distributing plant seeds. By February 2011, thousands began returning to their homes and farms. Many argue that we did not take action as soon as a crisis was predicted, resulting in thousands of deaths. A report titled “A Dangerous Delay”, states- "Waiting for a situation to reach crisis point before responding is the wrong way to address chronic vulnerability and recurrent drought in places like the Horn of Africa. The international community must change the way it operates to meet the challenge of recurrent crises … Long-term development work is best placed to respond to drought." Suzanne Dvorak, the chief executive of Save the Children also wrote that “politicians and policymakers in rich countries are often skeptical about taking preventative action because they think aid agencies are inflating the problem. Developing country governments are embarrassed about being seen as unable to feed their people. [...] these children are wasting away in a disaster that we could—and should—have prevented." Infant stricken with malnutrition during drought. I feel the same way as these people do. I think the the effects of this natural disaster could hav been reduced preventing it from becoming the terrible catastrophe it did. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network had anticipated this would happen in August 2010. Even with this information, the governments did not do enough to make sure the situation would not become critical. Millions of people’s lives were at risk, and they could have received help sooner, preventing many of deaths. I personally, had not even heard of this drought until I wrote this paper. I think it was kind of like a hush hush situation for a while, with people not paying enough attention to what was happening to millions of people in Africa. It did not get very much attention internationally. There has been data showing that there has been climate change going on in this region of Eastern Africa, that may contributed to the severity of the crisis. It is growing increasingly warmer and drier, putting the area at risk of having another severe drought. This means that there needs to be action taken to prepare for another drought. They need to learn from what happened during this catastrophe, and take action to prevent something this severe from happening again. It has been said that the drought sparked the disaster, but it was human factors that turned it into a catastrophe. Aid was delayed for 6 months because of conflicts. Humanitarian agencies and national governments were also slow declaring the disaster a crisis. But worst of all, donors wanted proof before giving help. This could have been why levels got to famine, and thousands were malnourished and dying before the world realized we needed to help them out. If the area had been preparing for this kind of thing to happen, and had a plan of what to do, thousands of lives could have been saved. This disaster had lasting effects on people in the region. Not only were they malnourished, but the ground was too dry to plant anything, and they had no water. Thousands lost their jobs and had to leave their homes and towns to find refuge. It had a profound effect on the economy as well. The area will have effects for quite some time, while trying to rebuild and bounce back from this disaster. Many have lost their loved ones through this terrible event. There were also others things triggered by this drought. It caused breakouts of disease and sickness, and more spreading of HIV/AIDS. The drought of the Horn of Africa was a tragic catastrophe. I was shocked by how much I learned about it, and the frightening things I realized happened there. I hope we will all learn from what happened in this situation, and prepare for others things like this in the future. Works Cited: Tisdall, Simon. "East Africa's Drought: The Avoidable Disaster." The Guardian. The Guardian, 17 Jan. 2012. Web. 01 Dec. 2013 Tutton, Mark, Isha Sesay, Michael Holmes, and Elise Labott. "10 Million at Risk from East Africa Drought." CNN. Cable News Network, 09 July 2011. Web. 01 Dec. 2013. "2011 East Africa Drought." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Nov. 2013. Web. 29 Nov. 2013.