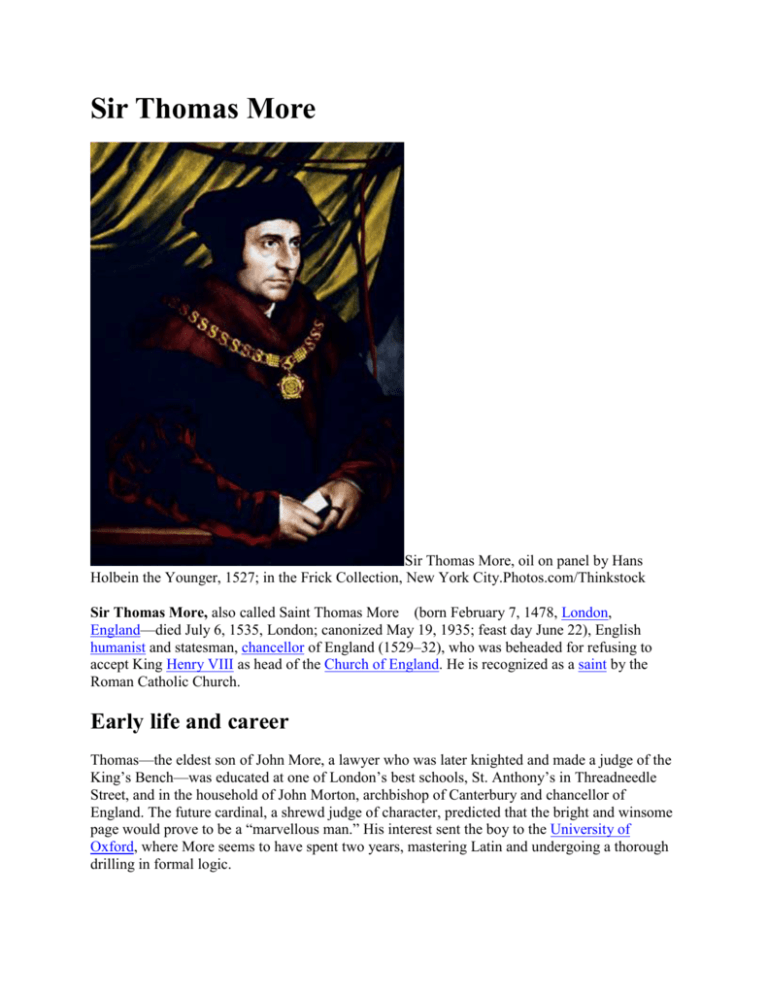

Sir Thomas More

advertisement

Sir Thomas More Sir Thomas More, oil on panel by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1527; in the Frick Collection, New York City.Photos.com/Thinkstock Sir Thomas More, also called Saint Thomas More (born February 7, 1478, London, England—died July 6, 1535, London; canonized May 19, 1935; feast day June 22), English humanist and statesman, chancellor of England (1529–32), who was beheaded for refusing to accept King Henry VIII as head of the Church of England. He is recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. Early life and career Thomas—the eldest son of John More, a lawyer who was later knighted and made a judge of the King’s Bench—was educated at one of London’s best schools, St. Anthony’s in Threadneedle Street, and in the household of John Morton, archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor of England. The future cardinal, a shrewd judge of character, predicted that the bright and winsome page would prove to be a “marvellous man.” His interest sent the boy to the University of Oxford, where More seems to have spent two years, mastering Latin and undergoing a thorough drilling in formal logic. About 1494 his father brought More back to London to study the common law. In February 1496 he was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn, one of the four legal societies preparing for admission to the bar. In 1501 More became an “utter barrister,” a full member of the profession. Thanks to his boundless curiosity and a prodigious capacity for work, he managed, along with the law, to keep up his literary pursuits. He read avidly from Holy Scripture, the Church Fathers, and the classics and tried his hand at all literary genres. Although bowing to his father’s decision that he should become a lawyer, More was prepared to be disowned rather than disobey God’s will. To test his vocation to the priesthood, he resided for about four years in the Carthusian monastery adjoining Lincoln’s Inn and shared as much of the monks’ way of life as was practicable. Although attracted especially to the Franciscan order, More decided that he would best serve God and his fellowmen as a lay Christian. More, however, never discarded the habits of early rising, prolonged prayer, fasting, and wearing the hair shirt. God remained the centre of his life. In late 1504 or early 1505, More married Joan Colt, the eldest daughter of an Essex gentleman farmer. She was a competent hostess for non-English visitors, such as the Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who was given permanent rooms in the Old Barge on the Thames side in Bucklersbury in the City of London, More’s home for the first two decades of his married life. Erasmus wrote his Praise of Folly while staying there. The important negotiations More conducted in 1509 on behalf of a number of London companies with the representative of the Antwerp merchants confirmed his competence in trade matters and his gifts as an interpreter and spokesman. From September 1510 to July 1518, when he resigned to be fully in the king’s service, More was one of the two undersheriffs of London, “the packhorses of the City government.” He endeared himself to the Londoners—as an impartial judge, a disinterested consultant, and “the general patron of the poor.” More’s domestic idyll came to a brutal end in the summer of 1511 with the death, perhaps in childbirth, of his wife. He was left a widower with four children, and within weeks of his first wife’s death he married Alice Middleton, the widow of a London mercer. She was several years his senior and had a daughter of her own; she did not bear More any children. More’s History of King Richard III, written in Latin and in English between about 1513 and 1518, is the first masterpiece of English historiography. Though never finished, it influenced succeeding historians. William Shakespeare is indebted to More for his portrait of the tyrant. The Utopia Map of the island of Utopia, woodcut by Ambrosius Holbein, 1518; from the 1518 edition of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia.© Photos.com/ThinkstockIn May 1515 More was appointed to a delegation to revise an AngloFlemish commercial treaty. The conference was held at Brugge, with long intervals that More used to visit other Belgian cities. He began in the Low Countries and completed after his return to London his Utopia, which was published at Leuven in December 1516. The book was an immediate success with the audience for which More wrote it: the humanists and an elite group of public officials. Utopia is a Greek name of More’s coining, from ou-topos (“no place”); a pun on eu-topos (“good place”) is suggested in a prefatory poem. More’s Utopia describes a pagan and communist citystate in which the institutions and policies are entirely governed by reason. The order and dignity of such a state provided a notable contrast with the unreasonable polity of Christian Europe, divided by self-interest and greed for power and riches, which More described in Book I, written in England in 1516. The description of Utopia is put in the mouth of a mysterious traveler, Raphael Hythloday, in support of his argument that communism is the only cure against egoism in private and public life. Through dialogue More speaks in favour of the mitigation of evil rather than its cure, human nature being fallible. Among the topics discussed by More in Utopia were penology, state-controlled education, religious pluralism, divorce, euthanasia, and women’s rights. The resulting demonstration of his learning, invention, and wit established his reputation as one of the foremost humanists. Soon translated into most European languages, Utopia became the ancestor of a new literary genre, the utopian romance. Years as chancellor of England Together with Tunstall, More attended the congress of Cambrai at which peace was made between France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1529. Though the Treaty of Cambrai represented a rebuff to England and, more particularly, a devastating reverse for Cardinal Wolsey’s policies, More managed to secure the inclusion of his country in the treaty and the settlement of mutual debts. When Wolsey fell from power, having failed in his foreign policy and in his efforts to procure the annulment of the king’s marriage to Catherine, More succeeded him as lord chancellor on October 26, 1529. On November 3, 1529, More opened the Parliament that was later to forge the legal instruments for his death. As the king’s mouthpiece, More indicted Wolsey in his opening speech and, in 1531, proclaimed the opinions of universities favourable to the divorce; but he did not sign the letter of 1530 in which England’s nobles and prelates, including Wolsey, pressured the pope to declare the first marriage void, and he tried to resign in 1531, when the clergy acknowledged the king as their supreme head, albeit with the clause “as far as the law of Christ allows.” More’s longest book, The Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer, in two volumes (1532 and 1533), centres on “what the church is.” To the stress of stooping for hours over his manuscript More ascribed the sharp pain in his chest, perhaps angina, which he invoked when begging Henry to free him from the yoke of office. This was on May 16, 1532, the day when the governing body (synod) of the church in England delivered to the crown the document by which they promised never to legislate or so much as convene without royal assent, thus placing a layperson at the head of the spiritual order. More meanwhile continued his campaign for the old faith, defending England’s antiheresy laws and his own handling of heretics, both as magistrate and as writer, in two books of 1533: the Apology and the Debellacyon. He also laughs away the accusation of greed leveled by William Tyndale, translator of parts of the first printed English Bible. More’s poverty was so notorious that the hierarchy collected £5,000 to recoup his polemical costs, but he refused this grant lest it be construed as a bribe. Indictment, trial, and execution The Arrest and Execution of Sir Thomas More in 1535, oil on panel by Antoine Caron; in the Musée de Blois, Blois, France. 116 × 143 cm.© Photos.com/ThinkstockMore’s refusal to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn, whom Henry married after his divorce from Catherine in 1533, marked him out for vengeance. Several charges of accepting bribes recoiled on the heads of his accusers. In February 1534 More was included in a bill of attainder for alleged complicity with Elizabeth Barton, who had uttered prophecies against Henry’s divorce, but he produced a letter in which he had warned the nun against meddling in affairs of state. He was summoned to appear before royal commissioners on April 13 to assent under oath to the Act of Succession, which declared the king’s marriage with Catherine void and that with Anne valid. This More was willing to do, acknowledging that Anne was in fact anointed queen. But he refused the oath as then administered because it entailed a repudiation of papal supremacy. On April 17, 1534, he was imprisoned in the Tower. More welcomed prison life. But for his family responsibilities, he would have chosen for himself “as strait a room and straiter too,” as he said to his daughter Margaret, who after some time took the oath and was then allowed to visit him. In prison, More wrote A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation, a masterpiece of Christian wisdom and of literature. His trial took place on July 1, 1535. Richard Rich, the solicitor general, a creature of Thomas Cromwell, the unacknowledged head of the government, testified that the prisoner had, in his presence, denied the king’s title as supreme head of the Church of England. Despite More’s scathing denial of this perjured evidence, the jury’s unanimous verdict was “guilty.” Before the sentence was pronounced, More spoke “in discharge of his conscience.” The unity of the church was the main motive of his martyrdom. His second objection was that “no temporal man may be head of the spirituality.” Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, to which he also referred as the cause for which they “sought his blood,” had been the occasion for the assaults on the church: among his judges were the new queen’s father, brother, and uncle. More was sentenced to the traitor’s death—“to be drawn, hanged, and quartered”—which the king changed to beheading. During five days of suspense, More prepared his soul to meet “the great spouse” and wrote a beautiful prayer and several letters of farewell. He walked to the scaffold on Tower Hill. “See me safe up,” he said to the lieutenant, “and for my coming down let me shift for myself.” He told the onlookers to witness that he was dying “in the faith and for the faith of the Catholic Church, the king’s good servant and God’s first.” He altered the ritual by blindfolding himself, playing “a part of his own” even on this awful stage. The news of More’s death shocked Europe. Erasmus mourned the man he had so often praised, “whose soul was more pure than any snow, whose genius was such that England never had and never again will have its like.” The official image of More as a traitor did not gain credence even in Protestant lands. Assessment Though the triumph of Anglicanism brought about a certain eclipse of Thomas More, the publication of the state papers restored a fuller and truer picture of More, preparing public opinion for his beatification (1886). He was canonized by Pius XI in May 1935. Though the man is greater than the writer and though nothing in his life “became him like the leaving of it,” his “golden little book” Utopia has earned him greater fame than the crown of martyrdom or the million words of his English works. Erasmus’s phrase describing More as omnium horarum homo was rendered later as “a man for all seasons” and was given currency by Robert Bolt’s play A Man for All Seasons (1960). Monuments to More have been placed in Westminster Hall, the Tower of London, and the Chelsea Embankment, all in London. In the words of the English Catholic apologist G.K. Chesterton, More “may come to be counted the greatest Englishman, or at least the greatest historical character in English History.” The Rev. Germain P. Marc’hadour "Sir Thomas More". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 05 Feb. 2015 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/392018/Sir-Thomas-More