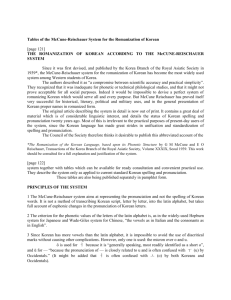

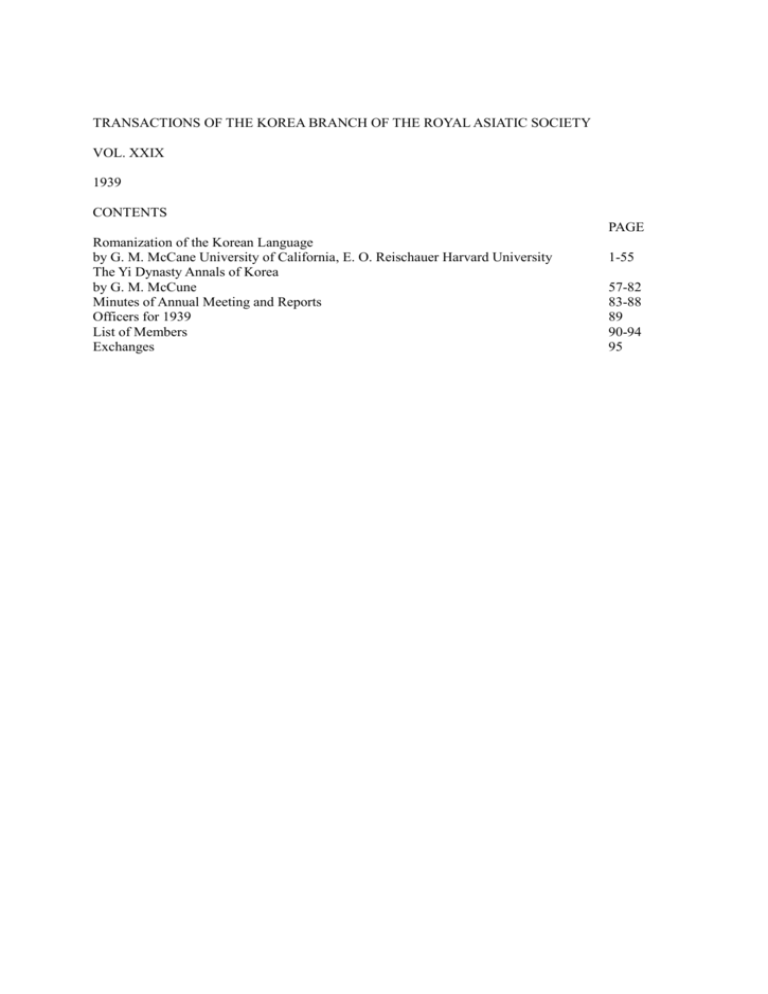

Volume XXIX

advertisement