SCIENCE CRAP

advertisement

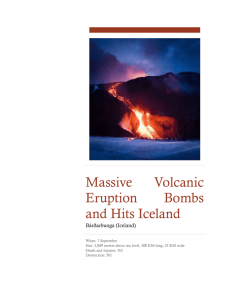

Can you imagine awaking from your sleep to see a curtain of fire from your backyard? This is what the residents of Heimaey, an island off the coast of Iceland, experienced on the night of January 23, 1973. What the authorities did not know was that a new volcano was forming close to the 5000-year-old Helgafell volcano. The following is a personal communication between a scientist from the University of Iceland to an official of the government of Iceland on the mainland. Communication from S.Thorarinsson to Flosi Hrafn Sigurdsson The following cable was received . . . on 23 January 1973. "An intense volcanic eruption on the east side of the mountain Helgafell, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland, was observed at 0155 GMT on 23 January 1973. Lava is flowing eastwards from a fissure some 1,500 m long. Approximate location: Latitude 63°26' N, Longitude 20°16' W. The eruption was preceded by a swarm of small earthquakes on 22 and 23 January. The largest earthquake was 2.6 on the Richter scale. The nearby town of Vestmannaeyjar, inhabited by about 5,000 people, has been mostly evacuated to the mainland. No casualties." S. Thorarinsson, Science Institute, University of Iceland; Flosi Hrafn Sigurdsson, Iceland Meteorological Office. The New Volcano: Eldfell On the morning of Tuesday, 23rd January 1973, at 1.55.a.m., an eruption began from a 1600metre fissure on the eastern side of Heimaey in the Westman Islands. The eruption came without warning and was totally unexpected. A few mild shocks had been felt from 10 p.m. that night, the sharpest of them occurring at 1.40 a.m. On Monday night, 22nd January, people in Heimaey went to bed at the usual time, as on a normal weekday. All the boats were in the harbor, for during the day there had been a south-easterly gale, force 12, with rainfall. Just before 2 a.m. there was a telephone call to the police station in the town center. Information was received that an eruption had started a short distance above and east of Kirkjubær," the church farm" at the easternmost end of the town. The police officers on duty immediately drove to the area, where they found the fissure east of Kirkjubær had now opened all the way to the sea to the north, and southwards east of Helgafell, as far as they could see. The whole length of the fissure was erupting, with a row of lava fountains so close to one another that it was like an unbroken wall of fire. The eruption began in what is now the main crater of the new volcano, later known as Eldfell. From the beginning lava ran down the slope from the fissure east and north-east. Soon the fire alarm was sounded, while fire and police cars patrolled the streets with sirens going in order to wake people. Within about two hours most of the population was afoot. People then began to stream down to the harbor, having just had time to put on the most necessary warm clothing and gather together a few belongings. Thanks to the gale of the previous day there were between 60-70 boats in the harbor. Vessels and other ships that had taken shelter there were now hurriedly prepared for departure, and the fist left for Þorlákshöfn at 2.30 a.m. followed by a steady stream. For reasons of safety, the town council decided that night to evacuate the whole population, apart from those employed on essential work. There was a danger of the harbor approaches being sealed off, should the fissure extend any further northwards, while the airfield might be closed, too, if it extended southwards. Contact was also made with Icelandair, the smaller airways companies in Reykjavik, and the NATO Defense Force in Keflavik. Aircraft from all these landed on Heimaey, for it was good flying weather, and during the night 300 people, mostly the sick and aged, were transported to Reykjavik by air. Some time after 4 a.m. the State Radio began to broadcast announcements and news reports on the eruption. Thus it may be reckoned that about 5,000 people were evacuated from Heimaey on the first night of the eruption, most of them by boat. The whole operation went remarkably smoothly and without mishap, thanks above all the favorable weather that night, but also to the calmness of the people in face of the calamity that had overwhelmed them. By the morning of Tuesday, 23rd January the most urgent rescue operations had, therefore, been completed and the islanders escaped unscathed from the greatest peril that had ever threatened the population of an urban area in Iceland. Between two and three hundred stayed behind to carry out essential duties. Recent Geologic Activity: Selfoss: June 17th 2000. A large earthquake (6.2 on the Richter Scale) struck southern Iceland at 15:40 local time. The tremors knocked off power in large areas, including the Westman Islands. The telephone system and some radio transmitters were also off the air for a while. This is largest earthquake southern Iceland has seen since 1896 when a lot of buildings were damaged in a large-scale quake On January 23, 1973, a fissure opened on the eastern side of Heimaey at approximately 1:00 a.m. It was 1,100 yards from the center of the town of Vestmannaeyjar. The fissure was one and one-quarter miles long and spread from one side of the island to another. In the beginning, fountains of lava spouted all along the fissure but soon the activity reduced to a small area onehalf mile from Helgafell Mountain. While the fissure was erupting, underwater volcanic activity was occurring at both ends of the fissure vent and it continued for three days. Within a two-day period, a cinder cone developed and projected upwards 110 yards above sea level. This newly created mountain was named Eldfell. Eldfell spewed lava and tephra (airborne ash, rock fragments and volcanic bombs) at a rapid rate. Strong winds developed and caused the tephra fallout to reach the town of Vestmannaeyjar. Many homes were buried. A few weeks later, the tephra activity subsided but a large flow of lava spread to the eastern side of town. The approaching lava headed in the direction of the harbor. This posed a threat to the fishing industry. By the end of February, Eldfell grew larger and was standing at 200 yards high. Lava continued to flow steadily and carried large blocks of rock from the cone, plus volcanic bombs were created. In late March, another lava flow headed for Vestmannaeyjar and covered more houses and obliterated the power plant. Eruptions and lava flows continued for several months. More houses and commercial buildings were buried or caught fire from flying lava rocks. By July 1973, the flow of lava was no longer visible but activity continued below the earth’s surface for a while longer. According to a USGS General Interest Publication, Man Against Volcano: The Eruption of Heimaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland, “preliminary estimates about 300 million cubic yards of tephra were deposited on and adjacent to Heimaey. By early May this flow as 10 to 23 yards high at its front, averaged more than 40 yards thick, and was as much as 110 yards thick in places.” Damage Caused by the Eruption of Eldfell in Iceland The underwater volcanic activity also severed the water pipeline and electric cable connected to mainland Iceland. As a result, the island of Heimaey had no drinking water or electricity. Further in the USGS General Interest publication, “by early May, 300 buildings were buried by lava flows or destroyed by fire. An additional 60 to 70 homes were buried by tephra.” Part of the harbor was filled in by lava and tephra. This had a negative impact on the fishing industry, which is the main source of employment in Vestmannaeyjar. It also impacted the economy of Iceland because fish is exported to other countries. Although one-third of the town of Vestmannaeyjer was destroyed by the eruption of Eldfell, crews of volunteers and emergency services reduced potential damage by spraying seawater onto the lava flows. They managed to stop or re-route the lava. The volunteers also tried to save buildings by clearing tephra from the rooftops and covering the windows with corrugated metal sheets. No lives were lost in Vestmannaeyjer because there was already a disaster plan in place. All residents were evacuated on fishing boats a few hours after the first eruption. The Icelandic town of Vestmannaeyjer is dwarfed by the erupting Eldfell volcano, which formed suddenly on the eastern edge of the city in January 1973. Eldfell destroyed much of Vestmannaeyjer and prompted the evacuation of the entire island of Heimaey. Today, Vestmannaeyjar is once again the premier fishing port in Iceland, and townspeople have planted grass on the lower slopes of the now-silent volcanic cone. On the morning of Tuesday 23rd January, 1973, at 1.55.a.m., an eruption began from a 1600metre fissure on the eastern side of Heimaey in the Vestmann Islands. The eruption came without warning and was totally unexpected. A few mild shocks had been felt from 10 p.m. that night, the sharpest of them occurring at 1.40 a.m. On Monday night, 22nd January, people in Heimaey went to bed at the usual time, as on a normal weekday. All the boats were in harbour, for during the day there had been a south- easterly gale, force 12, with rainfall. Just before 2 a.m. there was a telephone call to the police station in the town centre . Information was received that an eruption had started a short distance above and east of Kirkjubær," the church farm" at the easternmost end of the town. The police officers on duty immediately drove to the area, where they found the fissure east of Kirkjubær had now opened all the way to the sea to the north, and southwards east of Helgafell, as far as they could see. The whole length of the fissure was erupting, with a row of lava fountains so close to one another that it was like an unbroken wall of fire. The eruption began in what is now the main crater of the new volcano, later known as Eldfell. From the beginning lava ran down the slope from the fissure east and north- east, and at once started to form a lava salient out to sea. Soon the fire alarm was sounded, while fire and police cars patrolled the streets with sirens going in order to wake people. Within about two hours most of the population was afoot. People then began to stream down to the harbour, having just had time to put on the most necessary warm clothing and gather together a few belongings. Thanks to the gale of the previous day there were between 60-70 boats in the harbour. Both island boars and others that had taken shelter there were now hurriedly prepared for departure, and the fist left for Þorlákshöfn at 2.30 a.m. followed by a steady stream. For reasons of safety the town council decided that night to evacuate the whole population, apart from those employed on essential work. There was a danger of the harbour approaches being sealed off, should the fissure extend any further northwards, while the airfield might be closed, too, if it extended southwards. Contact was also made with Icelandair, the smaller airways companies in Reykjavík, and the NATO Defence Force in Keflavík. Aircraft from all these landed on Heimaey, for it was good flying weather, and during the night 300 people, mostly the sick and aged, were transported to Reykjavík by air. Some time after 4 a.m. the State Radio began to broadcast announcements and news reports on the eruption. Thus it may be reckoned that about 5,000 people were evacuated from Heimaey on the first night of the eruption, most of them by boat. The whole operation went remarkably smoothly and without mishap, thanks above all the favourable weather that night, but also to the calmness of the people in faxe of the calamity that had overwhelmed them. By the morning of Tuesday 23rd January the most urgent rescue operations had therefore been completed and the islanders escaped unscathed from the greatest peril that had ever threatened the population of an urban area in Iceland. Between two and three hundred stayed behind to carry out essential duties One of the most destructive volcanic eruptions in the history of Iceland began in the early morning of January 23, 1973, near the Nation's premier fishing port, the town of Vestmannaeyjar (Vést-mun-ayar), on Heimaey (Háme-a-ay), the only inhabited isle in the Vestmannaeyjar volcanic archipelago. ... The 1973 eruption on Heimaey was also the second major eruption (the other being Surtsey) definitely know to have occurred in Vestmannaeyjar since the settlement of Iceland in the ninth century, although there is evidence of a submarine eruption in the archipelago in September 1896. ... The 1973 eruption began just before 1 a.m., January 23, on the eastern side of Heimaey, approximately 1,100 yards from the center of town. A north-northeast-trending fissure rapidly opened to a length of about 1.25 miles, traversing the island from one shore to the other. Spectacular continuous lava fountains (curtain of fire) played in the initial phase of the eruption, but the activity soon consolidated to a small area along the fissure about one-half mile northeast of Helgafell. Also during the first 3 days, submarine volcanic activity occurred just offshore at the north and south ends of the fissure vent. Within 2 days a cinder-spatter cone rose more than 110 yards above sea level and was later named Eldfell or "fire mountain" by the official Icelandic place name committee. The output of lava and tephra (a collective term for fragmental volcanic materials initially airborne, such as ash and bombs) was estimated to be about 130 cubic yards per second. Within a few days after the eruption, strong easterly winds resulted in a major fall of tephra on the town of Vestmannaeyjar, completely burying homes close to Eldfell. By early February the tephra fall slackened markedly, but a massive lava flow approached the eastern edge of the town and threated to fill in the harbor of Iceland's most important fishing port. Also in early February submarine activity just north of the fissure severed an electric power cable and a water pipeline which supplied electrical power and water from the Icelandic mainland. ... By the end of February the cinder-spatter cone was more than 200 yards high. The central crater of Eldfell fed a massive blocky (aa lava) flow which moved slowly but relentlessly toward the north, northeast, and east. By early May this flow as 10 to 23 yards high at its front, averaged more than 40 yards thick, and was as much as 110 yards thick in places. Its upper surface was littered with scoria (cinderlike fragments of dark cellular lava) and volcanic bombs, as well as large blocks from the main cone which broke off and were carried along with the flow. The largest block soon was dubbed "Flakkarinn" (The Wanderer). Some of these blocks of welded scoria were about 200 yards square and stood 20 yards above the general lava surface and were rafted more than 1,000 yards. Measurements made from a series of aerial photographs taken from the end of March to the end of April indicated that the lava was flowing as a unit about 1,000 yards long by 1,000 yards wide with an average speed of 3 to 9 yards per day. As the flow advanced to the north and east, large blocks slumped from the cone on February 19 and 20 and moved toward the southeastern part of town. Also in late March a second large lava flow moved northwest on the west side of the main flow and covered many houses and the town powerplant. By February 8, lava ejection dropped from about 130 cubic yards per second to 80 cubic yards per second; and by the middle of April to about 7 cubic yards per second. As noted before, easterly winds blew tephra over the town during the early stages of the eruption. By January 29, the thickness of tephra varied from less than 1 yard in the northwest part of town to more than 5 yards in the southeast part. The eruption stopped in early July 1973; flowing lava was no longer visible, although hidden subsurface flow may have continued for a while. ... According to preliminary estimates about 300 million cubic yards of tephra were deposited on and adjacent to Heimaey. ... The prolonged destruction related to the course of the eruption was twofold: the highly visible destruction of homes, public buildings and installations, commercial properties, and partial infilling of the harbor by tephra falls and lava flows; and the economic and social impact on the residents of Vestmannaeyjar, local commerce, and the national and international economy of Iceland. Within 6 hours after the eruption began, nearly all of Heimaey's 5,300 residents had been evacuated safely to the mainland. This rapid evacuation was accomplished through the foresight of the Icelandic State Civil Defnese Organization, which had a continency evacuation plan ready for just such a disaster. The fishing fleet in port expediated the evacuation. Homes and farmsteads close to the rift were soon destroyed by tephra burial or fire from lava bombs and flows. The heavy tephra fall caused severe property damage a few days after the onset of the eruption. Numerous homes were completely buried by tephra, set afire by glowing lava bombs, or overridden by the advancing front of lava flows. Although many structures collapsed from the weight of the tephra, dozens were saved by crews of volunteers who cleared the roofs of accumulated tephra and tacked corrugated iron "shutters" over the windows. ... By early May, some 300 buildings had been engulfed by lava flows or gutted by fire, and another 60 to 70 homes had been buried completely by tephra The eruption caused a major crisis for the island and nearly led to its permanent evacuation. Volcanic ash fell over most of the island, destroying many houses, and a lava flow threatened to close off the harbour, the island's main income source via its fishing fleet. An operation was mounted to cool the advancing lava flow by pumping sea water onto it, which was successful in preventing the loss of the harbour. After the eruption finished, the islanders used heat from the slowly cooling lava flows to provide hot water and to generate electricity. They also used some of the extensive tephra, fallout of airborne volcanic material, to extend the runway at the island's small airport, and as landfill, on which 200 new houses were built. Eldfell is a composite volcanic cone just over 200 metres (660 ft) high on the Icelandic island of Heimaey. It formed in a volcanic eruption which began without warning just outside the town of Heimaey on 23 January 1973. Its name means Mountain of Fire in Icelandic.