OceanFluxGHGEvolution_RB_D60_v1-2

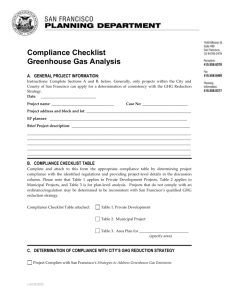

advertisement