Co-teaching version 6 - Jennica Brocious` ePortfolio (Masters)

advertisement

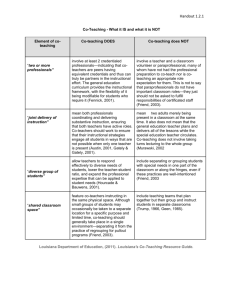

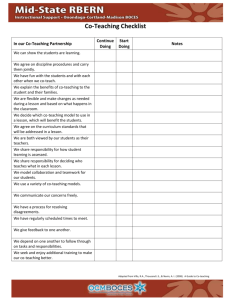

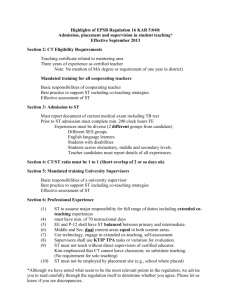

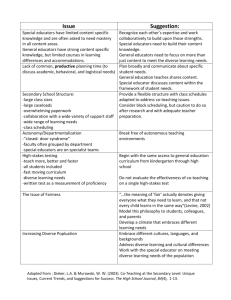

Running Head: CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 1 Co-teaching and Collaboration: Does the model of co-teaching used affect student performance? by Jennica S. Brocious A project submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION IN CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION WEBER STATE UNIVERSITY Ogden, Utah (Date) Approved ____________________________________ Committee Chair, Melina Alexander, Ph.D ____________________________________ Committee Member, Patrick Leytham, Ph.D ____________________________________ Committee Member, Kristine Geier M.ED CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 2 NATURE OF THE PROBLEM Helping students succeed in the classroom has led to schools utilizing their resources with more effective and creative means such as co-teaching (Kohler-Evans, 2006). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires students with disabilities be taught in the lease restrictive environment (LRE) and the co-teaching model is designed to include students with disabilities into a regular classroom while providing necessary accommodations (Nichols, Dowdy & Nichols, 2010). Co-teachers need to work on their relationship and find a balance for their roles as content and process specialists in order to help all students in the classroom (Wilson, 2008). Further research is needed to understand when, where and with whom co-teaching is best implemented (Murawski & Swanson, 2001). Co-teaching is a research-based intervention often used to help students with learning disabilities access the general curriculum and experience success in the education environment. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) support but do not mandate co-teaching as a response to intervention (RTI) (Brown, Howerter, &Morgan, 2013). NCLB has had a major effect on the amount of co-teaching in schools since its implementation. More than half of the students with a specific learning disability spend 80% of their time in the general education setting (Cortiella, 2007). How well co-teaching works in the classroom is often dependent on how well the teachers get along. In a series of four case studies, Mastropieri, Scruggs, Graetz, Norland, Gardizi & McDuffie (2005) found that the relationship of the co-teachers became a critical variable that predicted whether students with disabilities would have success in the inclusive environment. Often, teachers are assigned a co-teaching partner without being given the choice of whom they will be working, and the relationship can be strained from the beginning (Kohler- CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 3 Evans, 2006). The relationship that co-teachers develop throughout the year helps establish protocols and the environment in the classroom impacting the success of the strategy (KohlerEvans, 2006). Although co-teaching has demonstrated effective at giving students needed support, many teachers are unsure how to implement co-teaching into their classrooms. Unless teachers have a clear knowledge of the most effective co-teaching technique, students are unlikely to experience the full benefit of co-teaching. Co-teachers are frequently placed together with little or no training and therefore are unsure about what model to use in the classroom and how to implement a successful co-teaching partnership (Murawski & Dieker, 2004). Often, co-teachers lean toward the model, "one teach, one observe" because they do not know there are other ways to co-teach (Scruggs, Mastropieri, & McDuffie, 2007). Murawski & Swanson (2001) claim that more research will give experts a better understanding of the relationship between the special educator and general educator. This research relates to finding the best model of collaborative teaching to help meet the needs of students with disabilities. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 4 Literature Review This literature review will first discuss the aspects of No Child Left Behind and IDEA in how it relates to classrooms becoming a more inclusive setting when teaching students with disabilities. Second, the literature review will focus on the research about the co-teachers’ relationship and how that can lead to a successful environment. Next, the six universally accepted models of co-teaching will be examined. Lastly, this review will review co-teaching models most frequently used in research and their outcomes. Co-Teaching and No Child Left Behind In 1997, the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) added further amendments with a main goal to allow students with disabilities the opportunity to access the same curriculum given to their non-disabled peers in the least restrictive environment (Nichols, Dowdy & Nichols, 2010). The law was then reauthorized in 2004, with the most recent changes in regulations occurring in 2006. The final regulations regarding the alignment between IDEA and No Child Left Behind (NCLB) set a new standard of how students with disabilities were taught, by encouraging reading first, wanting to ensure that every child could read by the end of third grade (U.S. Department of Education, 2001). Many schools throughout the country opted to allow students with disabilities to be taught in several different ways knowing that it is required through the continuum of services. Some of the more common options include an inclusion classroom instead of being pulled out during the day at the elementary level, a resource classroom, where students are taught in small groups daily, or give students at least one period a day when they receive special education services at the secondary level. Co-teaching was not mandated by either IDEA or NCLB but was supported. It has become a trend for providing CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 5 educational services to students with disabilities in the general education environment (Ploesl, Rock, Schoenfeld, & Banks 2010; Pugach & Winn, 2011). In a study reviewing Nichols, Dowdy and Nichols (2010) noted that from the twentyfour school districts observed, many implemented co-teaching as a way to meet the mandate of NCLB. A problem arose when schools initiated co-teaching without proper staff development for both the special education teacher and the regular education teacher. It appeared that educators were implementing co-teaching to comply with NCLB and as an RTI for students with disabilities (Nichols et al., 2010). NCLB also set out a requirement that all students, including those with disabilities, be taught by a highly qualified teacher in the least restrictive environment. By implementing co-teaching in the school, legislative expectations were being met while students with disabilities were being taught with the instruction and support they required (Friend, et al., 2010). Co-teaching is not a product of NCLB. Prior to NCLB, co-teaching was already initiating collaborative opportunities between general educators and special educators. In 1993, discretionary funds of the IDEA act were granted to the Northwestern State University of Louisiana special education department to bring about a collaborative effort between teachers (Duchardt, Marlow, Inman, Christensen & Reeves, 1999). The co-planning and co-teaching arrangements found nine positive outcomes: collaborating and developing trust, finding time to co-plan, learning by trial and error, meeting the needs of diverse learners, learning to be more flexible and collegial, helping teachers to become problem solvers, forming and building partnerships, solving problems as a team, and lastly challenging oneself and developing professionally. Limitations were not listed in the study, but making time to meet together as coteachers seemed to be inherent (Duchardt et al., 1999). CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 6 What is co-teaching? There are many forms of co-teaching, but the overall definition is two educators, -- for special education this means a special education teacher and a general education teacher, in the classroom providing instruction and support to all students (Kohler-Evans, 2006). Co-teaching is not a teacher and an assistant, teacher’s aide, or paraprofessional; co-teaching is two or more coequal faculty members working together (Dieker & Murawski, 2003). Co-teaching involves both the general educator and the special educator jointly giving instruction to a diverse group of students. Student needs influence the type of co-teaching that is executed in the classroom (Friend, Cook, Hurley-Chamberlain &Shamberger, 2010). Co-teaching can look different in a classroom depending on the model used for a lesson. Types of Co-Teaching Many researchers have agreed that there are six different types of co-teaching (Friend, Cook, Hurley-Chamberlain &Shamberger, 2010; Sileo, 2011; Solis, Vaughn, Swanson & McCulley, 2012). One Teach, One Observe: One of the teachers is responsible for the instruction and lesson of the classroom while the other teacher observes classroom behavior. The co-teachers are given the opportunity to collect data on their students' academic, social and behavioral skills as well as each other. Parallel Teaching: Students are separated into two equal groups and placed at different ends of the classroom. Each small group is taught by one of the teachers teaching the same material. This allows for students to be taught in a small group setting and gives more opportunities for students to respond to the different forms of instruction. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 7 Station Teaching: Students are divided into three groups and are directed to a station in the classroom. At two stations a teacher will teach the students material and at one station the students will work individually. The material presented at each station is nonsequential so that it does not matter at what station the students start. This allows for students to have plenty of student-to-teacher interaction as they will be with a teacher in two out of the three stations. Alternative Teaching: One teacher is teaching the majority of the classroom while the other teacher takes a small group and teaches them separately. The small group can change according to the needs of the students. Students can be pre-taught concepts, given additional help on harder concepts, work on vocabulary development or enrichment activities for a short period of time. One Teach, One Assist: One teacher gives instruction to the whole classroom while the other teacher monitors students to assess who needs individual help. This helps students receive individualized help in the classroom without leaving the classroom. Team Teaching: Both teachers are in front of the classroom instructing by taking turns. Teachers may show opposite views and lead a discussion in the classroom. They may also show a variety of ways on how to solve a problem. This type of co-teaching benefits students by enabling them to see different points of view. Friend, et al. (2010) agreed that with the co-teaching approach, teachers are able to address students with disabilities individualized educational program (IEP) goals and objectives while still being taught in the least restrictive environment and obtaining access to the general curriculum. Understanding that there are six different models of co-teaching, teachers need to meet with one another and plan out units to be taught with more than one model in mind. It is CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 8 important for teachers to choose a structure that complements the students' abilities in the classroom and the lesson given (Sileo, 2011). By planning together what type of model should be taught, teachers help strengthen and build their relationship to create a successful learning environment. Co-Teachers Relationship Murawski and Dieker (2004), stated that a co-teaching collaborative relationship can be doomed from the start if one teacher leads in a different direction than the other teacher expects, or if one partner is more domineering over territory and content area. Some schools may decide to thrust co-teaching onto teachers. This could be more harmful than beneficial to students because veteran teachers could feel insulted and special educators could feel homeless by not being welcome into the general education teachers classroom (Kohler-Evans, 2006). In the Kohler-Evans (2006) survey, research found that 77% of the participants said that co-teaching led students to achieve academic gains. The overall impact was positive on the students and the teachers. The majority of teachers replied a positive working relationship with the other teacher involved was the most important feature in a co-teaching relationship (Kohler-Evans, 2006). There are three main phases in a classroom that teachers need to discuss once their partnership is established: the planning, the instruction, and how the assessment will be handled. By meeting together and communicating, teachers are able to determine what instructional technique will be most effective and efficient in helping all students meet the academic standards (Murawski & Dieker, 2004). Teachers should try to get the same planning period if they are able or coordinate a time during the week to meet and build their relationship. Co-teachers should be doing just that, co-teaching: the special education teacher is planned to teach certain days or certain lessons and not just observe behavior the entire time. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 9 The most daunting aspect according to Murawski & Dieker (2004), of co-teaching is that co-teachers overcome how to share the instruction time in the classroom. Since the implementation of NCLB, high stakes testing has become a focal point of the classroom. Due to NCLB’s implementation, it is important that teachers not only plan lessons together, but also assessments. Teachers should talk about assessment, grading preferences, and philosophies about co-teaching to help provide purposeful assessment and prevent later misunderstandings or conflicts (Conderman & Hedin, 2012). Wilson (2008), researched how co-teachers can utilize their time in the classroom to create a beneficial learning environment for the students while the other teacher is presenting a whole class instruction. The co-teacher can walk around the room overseeing student performance and behavior, and cue students to focus and stay on task. The co-teacher can help by targeting a specific student or forming a mini-group. Observing student behavior, questions, and responses allows for the co-teachers to adjust the lessons for future instruction. The coteacher can help make assignments, and adjust them for modifications that may need to be made for students with disabilities. The co-teacher is able to help by verbalizing possible confusion, sharing a different point of view, as well as helping with notes and homework (Wilson, 2008). Austin (2001) examined teachers’ beliefs about co-teaching. Results indicated that both special educators and general educators found that scheduled planning time, administrative support, and in-service training are needed to create a successful co-taught environment. One of the questions in the survey asked the teachers how they viewed their main role in the classroom. Special educators said their main role was to modify lessons and remediate. General educators felt they were responsible for the majority of the lesson planning and instruction (Austin, 2001). CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 10 By establishing roles in the classroom and sharing responsibilities rather than one teacher becoming the leader, co-teachers are able to grow and maintain a healthy relationship. Kohler-Evans (2006) also recommended that the main aspect for co-teachers in establishing a healthy relationship is to “communicate, communicate and communicate more.” Teachers can create unobtrusive signals to help communicate during a lesson, create the agenda together, and discuss their teaching style preferences (Murawski & Dieker, 2004). Co-teaching should be fun and give room for practice and mistakes. Co-teachers should remember that one size does not fit all. The key to a successful co-teaching partnership is compromise and collaboration (Sileo, 2011). Co-teaching Outcomes The research findings detailed above indicate teachers want a positive environment in their classroom but co-teaching can create tensions. Bouck, (2007), illustrated how this tension could be seen as a constraint or an opportunity for teachers. The co-teachers had more freedoms, supported each other and could play a new role in the classroom, but at the same time the coteachers felt that their role was devalued (Bouck, 2007). The relationship built by teachers allows for the classroom to either succeed or have difficulties. The benefits of co-teaching can be analyzed by the perceptions of students with disabilities, general education students, and the teachers involved. A three year study by Walther-Thomas (1997) looked at 18 elementary schools and seven middle schools, involving 119 teachers and 24 administrators. The aim of the study was to help understand the benefits and problems faced by students and educators (Walther-Thomas, 1997). Students with disabilities were observed experiencing more self-confidence and self-esteem by being included in the regular education setting. Researchers noted that students struggled at first to adjust to the higher CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 11 expectations of the classroom, but by the end of the year all students, including those in the general education population, showed academic progress. General education students were given teacher time and attention that they otherwise would not see in a one teacher environment. Also, general education students were able to learn new strategies and study skills. Co-teaching increased all students' social skills and peer relationships by helping create a classroom community (Walther-Thomas, 1997). Not only can co-teaching benefit students but also benefit teachers by allowing teachers to professionally grow. Teachers reported in the study to be professionally satisfied with their jobs and indicated they saw the programs improving over time. Co-teaching helped teachers support one another and additionally increased collaboration among the faculty members. Conversely, Walther-Thomas (1997), noted many problems, some becoming more serious the longer they were not addressed. Those problems included finding planning time to work together due to different preperation periods at a secondary level. Students with disabilities would often be scheduled into another resource class at the same time a co-taught class was taught, limiting their chances of being placed in a co-taught class. Another concern for the special educator was that co-teaching took time away from working on their case load. Some of the special educator's caseloads in the study were so large, they could not help the general education teacher meet demands for the co-taught class, creating a stressful situation. All participants in the study expressed they had administrative support, but would like more time to work on staff development to create a more cohesive environment (Walther-Thomas, 1997). Not every study concludes with mostly positive reactions to co-teaching. The studies of Magiera & Zigmond (2005) found when students with disabilities were co-taught they had more interaction with a teacher, yet if the special educator was not in the room the general educator CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 12 would interact less frequently with the student with disabilities. Whole classroom instruction was prevalent throughout the eleven middle schools that participated in the study, which suggests there was little training on co-teaching before it was implemented in the classroom (Magiera & Zigmond, 2005). Overall research suggests that co-teaching is beneficial for the students and if anyone is falling behind, it is the teachers in the classroom. In the survey by Bacharach, Heck & Dahlberg (2011), they noted five critical elements of co-operating teachers were: sharing leadership in the classroom, trust and respect for each other, communicating, along with planning, and teaching together. When looking at research, teachers should understand what type of co-teaching model is being used when planning lessons based on research. Co-Teaching Methods in Research Research by Gurgur & Uzuner (2011), studied the benefits of team teaching and station teaching in a second-grade classroom in a low-income district located in Turkey. The classroom had 33 students, with two students identified as needing special education. This was the first time that either teacher had worked with each other, and also the first time that either teacher was in a co-teaching assignment. The teachers tried to implement a team teaching approach where they would take turns teaching the classroom. In this classroom when the general educator was teaching, they often would forget to explain the objectives of the lesson and only provide whole classroom instruction. When the special educator was teaching, the general educator would interrupt the special educator to remind them about discipline problems happening in the classroom (Gurgur & Uzuner, 2011). When this particular pair of teachers then tried station teaching in the classroom the results were both positive and negative (Gurgur & Uzuner, 2011). Students were placed in CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 13 groups well, but there was a lack of instruction and management on how the groups rotated and how students were to manage themselves at the station where they were independent. During this time, the teachers were given co-planning and reflection meeting times, however, the meetings were not held or were short. This was due to the general educator not wanting to be involved in the process of co-teaching. The special educator cited that the general educator would arrive late and come unprepared to meetings. This behavior hindered the success of station teaching and team teaching in the classroom. The researchers noted that when cooperation from the general education teacher could not be accomplished, the co-teaching model of one-teach/one-assist would then be applied in the classroom as it requires less cooperation between the teachers (Gurgur & Uzuner, 2011). Embury (2010), researched student engagement and teacher perception when teachers changed their teaching strategy of one teach/one assist to parallel, team and station teaching. Embury looked at two students in three different classrooms, one with an IEP and one who was teacher recommended without any known disabilities, to compare their engagement levels between the co-teaching. The teachers participating in the study also received training prior to the collection of data. In the classroom that was modeling station teaching, students’ engagement increased, and students took responsibility for their own learning (Embury, 2010). The seventh grade math co-teachers who Embury studied were open to new ideas; both licensed in the content area, and had already worked with each other for quite some time. These teachers used the team teaching model and found that acknowledging each other’s skills helped to establish effective practices in the classroom (Embury, 2010). Embury (2010) then looked at student engagement levels and found that the mean of the engagement level of the six students observed during one teach/one assist was at 84.83%. There CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 14 was a higher engagement level for team teaching and station teaching among all six students with station teaching mean engagement levels at 93.83% and team teaching mean engagement levels at 91.16%. Two students were observed four times in a parallel teaching model and were measured with mean engagement levels of 94% (Embury, 2010). The goals in another study by Mageria, Smith, Zigmond & Gebauer (2005) sought to ascertain how co-teaching looked in the classroom and how it benefitted students. They found that in 24 of the 49 observed classrooms the special educator assumed the role of being an observer or assistant. Team teaching was observed in only nine out of the 49 classrooms, and across their entire study, only twenty minutes of observed time was small group or alternative teaching happening (Magiera, et al., 2005). The researchers concluded that special education teachers should examine their role as facilitators to help students understand the material. The special education teachers should also work with the general education teachers to enrich the lessons to be more dynamic than what normally happens in a mathematics classroom (Magiera, et al., 2005). Case studies conducted by Mastropieri et al. (2005) evaluated four different co-teaching examples. The first case study observed two teams of teachers during a unit on the ecosystem taught at the upper elementary and middle school grades. The research noted that these teams worked well due to their collaboration efforts but did not mention what models of co-teaching they used in the classroom. The second case study looked at how a middle school social studies team had struggles in their co-taught efforts due to co-planning, teaching style and behavior management. The third case study monitored three teams of co-teachers in a high school history setting and noted the roles each teacher played and how end-of-year testing had an emphasis in the classroom. A significant deficiency of the entire study is that only one model of co-teaching CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 15 was described across the studies, limiting the data analyzed. The classroom in the last case study identified as using the one-teach/one-assist model in a high school chemistry course. Due to lack of content knowledge, the special education teacher played more of a role as an aide, rather than a teacher (Mastropieri et al., 2005). Many special educators do not have a degree in the content taught. In these situations, it is important for special education teachers to become co-learners, and ask questions so they can be prepared to understand the main ideas of the lesson (Rice, Drame, Owens & Frattura, 2007). A noted deficit in the literature reviewed was the lack of specificity as to what coteaching model was implemented in the research (Solis, Vaughn, Swanson & McCulley, 2012). Even though there are six models of co-teaching, some models appear to be forgotten or overlooked in research such as one-teach/one observe. Instead it appears as a definition in a literature review before the research, rather than actual data studied. Also, research tends to lean toward station teaching and not on alternative teaching. Summary Closing the achievement gap has been a goal of the educational system. School districts have utilized co-teaching as a way to help reach that goal. The research suggests that some districts used co-teaching as a response to intervention rather than a research based decision to increase student performance. Co-teaching can be successful if the teachers are willing to put forth the effort and the time. Co-teaching presents challenges, yet by understanding what challenges can teachers work together to increase student success. There are different models of co-teaching yet research fails to illustrate if any particular model helps students more, but instead, it shows how the co-teaching model implemented in the classroom is more of a personal CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION preference. If presented well, co-teaching can help students succeed not only academically, but also personally. 16 CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 17 PURPOSE Based on the literature reviewed, co-teaching can provide benefits for teachers and students. Even though there are six models of co-teaching, the dominant model is “one-teach, one assist” which is not highly recommended, nor the most effective (Scruggs et al., 2007). Murawski & Swanson (2001) claimed more research into co-teaching models will help teachers build their relationship in order to help all students in the classroom. The purpose of this research is to assess students’ opinions and performance levels when taught using different models of coteaching, (a) team teaching and (b) a mixture of small group teaching combined with alternative teaching. By assessing students’ opinions and performance levels, the research will show what type of co-teaching model can be effective in helping increase student achievement and engagement levels. The research will focus on the following questions: 1) Which method of co-teaching do students prefer and why? 2) Which method of co-teaching do teachers prefer and why? 3) Does the model of co-teaching positively/negatively influence student academic performance? CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 18 METHOD In order to address the questions of this study, a survey approach will be used to gather data from students and teachers, as well as look at student outcomes and assess it by descriptive quantitative research methods. Two surveys will be used to answer research questions one and two, a student survey assessing student co-teaching preference and a teacher survey assessing teacher co-teaching preference. The last question to be addressed in this study will look at students’ pre and post test scores during the units taught and measure progress. Participants Participants chosen for this research will include a general education teacher with a coteaching background and a convenience sampling of 30 students in an eighth grade general education classroom at a Title One junior high located in northern Utah chosen due to their accessibility to the researcher. Approximately seven of the 30 students will be students identified as having disabilities. Teacher consent and parent consent/student assent will be obtained before students are allowed to participate in completing the survey. The special education co-teacher is also the researcher and will not fill out the survey due to possible bias. The co-teachers have received no formal training on co-teaching but will be familiarized with the different co-teaching models to be used. In addition teachers will share the same prep period to help with their coplanning. Instrumentation Each student will be given a multiple choice question test before each unit and the same question test after each unit (See Appendix A). The researcher created a survey (see Appendix B & C) for students and teachers based on the best practices determined by Johnson & Christensen (2008). Students will be given an online survey with a Likert scale to analyze which unit they CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 19 found helped them learn more at the end of both units. The teacher will also be given an online survey at the end of both units, to analyze which co-teaching method she preferred. In addition student performance will be collected on curriculum based assessments. Participants will receive the online survey to help the researcher collect data efficiently, the Likert scale is being used to obtain feedback and opinions from participants. Reliability and validity will be assured by checking questions by giving the survey to a pilot group. Procedure The researcher will first obtain Internal Review Board (IRB) approval for the proposed research. Once approved, the researcher will contact and obtain permission from the district and school to implement the research involving the students (See Appendix D & E). At the beginning of the school year, students will be given a letter of intent with consent informing parents about their students’ involvement in the research and asking for permission that they fill out a survey at the end of the study (See Appendix F). The survey will be created using SurveyGizmo and distributed to the students and teachers with a link attached to the researcher’s website for easy access. The survey consists of questions that will be answered by a Likert scale. The multiple choice question tests given to the students will be created by the researcher, who is the special educator co-teacher in the classroom, and the general education teacher. The test questions will vary in difficulty but will assess what the students know about the unit previous to the unit and what they have learned after the unit is over. One survey will assess students’ opinions on how they like to be taught. Another survey will assess which method of co-teaching teachers prefer to teach. By looking at both student and teacher opinions, the data will be analyzed as to whether there are agreements or disagreements depending on point of view. Before surveys are given, students in an eighth grade math class will CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 20 be taught two units using different methods of co-teaching. The first unit will be taught using a team teaching approach. The second unit will be taught using a mixture of small group and alternative teaching. The researcher and co-teacher will teach the units in this order as they have used the team teaching method in the past. The second unit, which will be taught with small group and alternative methods of co-teaching calls for more activities that can be implemented during its instruction. The first unit will be on the number system and will take approximately two weeks to complete. This unit will be taught with a team teaching approach. The general educator and special educator will take turns introducing the concepts and showing examples of how to solve the problem, giving students different points of view. The second unit is about one variable linear equations and will take about four weeks to complete. During this time the teachers will have activity days where students will be placed in small groups and rotate to stations in order to solve for the variable. Also there will be at least one day in each week of this unit where the teachers will identify students who need remediation to be pulled out and given a modified lesson and assignment. Remediation for the first unit will consist of flex time tickets where students will be flagged on an individual basis by their coordinating teacher. At the start of each unit students will be given a five question quiz to see what they know beforehand. Then at the end of each unit students will be given the same five question quiz and their progress will be charted along with other test and quiz scores taken in between. When both units are finished, students and teachers will be given a survey with a Likert scale asking questions about which approach to co-teaching they preferred. Data Analysis CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 21 Pre and post test quizzes for each unit will be analyzed to determine how students achieve academically when taught differently. Data will be collected from the surveys taken by the students and by the teacher. Data will be collected via the survey tool. Data will then be analyzed by looking at the means and percentages of each response. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 22 References Austin, V. L. (2001). Teachers' beliefs about co-teaching. Remedial and special education, 22(4), 245-255. Bacharach, N. L., Heck, T. W., & Dahlberg, K. R. (2011). What makes co-teaching work? Identifying the essential elements. College Teaching Methods & Styles Journal (CTMS), 4(3), 43-48. Bouck, E. C. (2007). Co-teaching…Not just a textbook term: Implications for practice. Preventing School Failure, 51(2), 46-51. Brown, N., Howerter, C. S., & Morgan, J. (2013). Tools and strategies for making co-teaching work. Intervention In School & Clinic,49(2), 84-91. doi:10.1177/1053451213493174 Conderman, G., & Hedin, L. (2012). Purposeful assessment practices for co-teachers. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(4), 18-27. Cortiella, C. (2007). Rewards and roadblocks: How special education students are faring under No Child Left Behind. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities. Retrieved from: http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Evaluatingperformance/Special-education-At-a-glance/Special-education-References.html Dieker, L. A., & Murawski, W. W. (2003). Co-teaching at the secondary level: Unique issues, current trends, and suggestions for success. The High School Journal, 86(4), 1-13. Duchardt, B., Marlow, L., Inman, D., Christensen, P., & Reeves, M. (1999). Collaboration and co-teaching: General and special education faculty. Clearing House, 72(3), 186. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 23 Embury, D. (2010) Does co-teaching work? A mixed method case study evaluation of coteaching as an intervention. University of Cincinnati. Friend, M., Cook, L., Hurley-Chamberlain, D., & Shamberger, C. (2010). Co-teaching: An illustration of the complexity of collaboration in special education. Journal Of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 20(1), 9-27. doi:10.1080/10474410903535380 Gurgur, H. & Uzuner, Y. (2011). Examining the implementation of two co-teaching models: team teaching and station teaching. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15:6, 589-610. doi: 10.1080/13603110903265032 Johnson, B. & Christensen, L., (2008). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Kohler-Evans, P. A. (2006). Co-teaching: How to make this marriage work in front of the kids.. Education, 127(2), 260-264. Nichols, J., Dowdy, A., & Nichols, C. (2010). Co-teaching: An educational promise for children with disabilities or a quick fix to meet the mandates of No Child Left Behind? Education, 130(4), 647-651. Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2005). Co‐teaching in middle school classrooms under routine conditions: Does the instructional experience differ for students with disabilities in co‐taught and solo‐taught classes?. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 20(2), 79-85. CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 24 Magiera, K., Smith, C., Zigmond, N., & Gebauer, K. (2005). Benefits of co-teaching in secondary mathematics classes. Teaching Exceptional Children, 37(3), 20-24. Mastropieri, M. A., Scruggs, T. E., Graetz, J., Norland, J., Gardizi, W., & McDuffie, K. (2005). Case studies in co-teaching in the content areas: Successes, failures, and challenges. Intervention In School & Clinic, 40(5), 260-270. Murawski, W. W., & Dieker, L. A. (2004). Tips and strategies for co-teaching at the secondary level. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36(5), 52-58. Murawski, W. W., & Swanson, H. L. (2001). A Meta-Analysis of Co-Teaching Research Where Are the Data?. Remedial and Special Education, 22(5), 258-267. Pugach, M.C., & Winn, J.A. (2011). Research on co-teaching and teaming: An untapped resource for induction. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 24, 36-46. Rice, N., Drame, E., Owen, L., & Frattura, E. M. (2007). Co-instructing at the secondary level. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(6), 12-18. Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & McDuffie, K. A. (2007). Co-teaching in inclusive classrooms: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Exceptional Children, 73(4), 392416. Sileo, J. M. (2011). Co-teaching: Getting to know your partner. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(5), 32-38. Solis, M., Vaughn, S., Swanson, E., & Mcculley, L. (2012). Collaborative models of instruction: The empirical foundations of inclusion and co-teaching. Psychology In The Schools, 49(5), 498-510. doi:10.1002/pits.21606 CO-TEACHING AND COLLABORATION 25 U.S. Department of Education, Elementary and Secondary Education Act. (2001). No Child Left Behind. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/nclb/overview/intro/execsumm.html Walther-Thomas, C. S. (1997). Co-teaching experiences: The benefits and problems that teachers and principals report over time. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 30(4), 395. Wilson, G. (2008). Be an active co-teacher. Intervention In School & Clinic, 43(4), 240-243.