Proposed Digest of Journal Articles for Public SES

advertisement

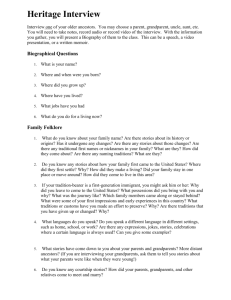

Issue 9 Public service traditions November 2012 APS Human Capital Matters: Public Service Traditions November 2012, Issue 9 Editor’s note to readers Welcome to the ninth edition of Human Capital Matters for 2012—the digest for time poor leaders and practitioners with an interest in human capital and organisational capability. This edition focuses on the role of the administrative tradition in shaping public sector thinking and practice. The recent publication of the Government White Paper on Australia in the Asian Century has focused attention on what Australia must do to work effectively with Asia in the future. A critical aspect of this for the APS will be its interaction with the civil services of these countries and fundamental to this is an understanding that there are differences in the administrative traditions of different countries. Anthony B. L. Cheung asserts that it is necessary to focus on the enduring effects of the Confucian tradition in studying Asia’s public services, especially those of Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, China and Taiwan. For Cheung, each of these societies shares ‘a common Confucian heritage of administrative culture’, but reflects this in distinctive ways1. Although awareness of administrative traditions has been around for a long time (e.g. AngloSaxon [or Anglo-American], Napoleonic), systematic study of the subject began in earnest among Western public administration scholars only in the late 1990s. It is also important to distinguish between the idea of an administrative and a governmental tradition (e.g. the Westminster tradition)—they are different things. One of the early papers on this subject was written by Bevir and his colleagues who advocated the integration of both government and administrative traditions in political and public administration study and practice. Nankervis et al, discuss the role of administrative traditions in the human resource practices of the public sectors of China and India. In their first article, Painter and Peters note the multi-dimensional nature of administrative traditions and while offering categories of tradition, they do so in geographical and historical terms rather than as a classification system. In their second article they argue the importance of administrative history and practice in understanding public sector reform. They also examine the interaction of traditions and external circumstances in shaping public administration. In the final article in this edition, Yesilkagit also examines the role of tradition in shaping public sector reform; the author notes that tradition involves not only the structure of administration but also the enduring beliefs and ideas about administration. About Human Capital Matters Human Capital Matters seeks to provide APS leaders and practitioners with easy access to the issues of contemporary importance in public and private sector human capital and organisational capability. It has been designed to provide interested readers with a monthly guide to the national and international ideas that are shaping human capital thinking and practice. Anthony B. L. Cheung, ‘Public Administration in East Asia: Legacies, Trajectories and Lessons’, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 78, No. 2, June 2012, p. 211. 1 2 Comments and suggestions welcome Thank you to those who took the time to provide feedback on earlier editions of Human Capital Matters. Comments, suggestions or questions regarding this publication are always welcome and should be addressed to: humancapitalmatters@apsc.gov.au. Readers can also subscribe to the mailing list through this email address. Mark Bevir, R. A. W. Rhodes and Patrick Weller, ‘Traditions of Governance: Interpreting the Changing Role of the Public Sector’, ‘Public Administration’, Vol. 81, No. 1, 2003, pp. 1–17. This article is an early and ambitious piece of advocacy for integrating knowledge of governmental, and in a more minor key, administrative traditions into political study and public administration scholarship and practice. The authors discuss the public sector reform approaches and foci which emerged in the 1980s and came to be known as new public management (NPM). They then examine the existing literature on NPM and conclude that it does not adequately explore the ways in which governmental traditions shape reform. Finally, they outline an interpretive approach to the analysis of public sector change built on the notions of beliefs (people’s convictions and desires); administrative traditions; dilemmas (accepting a new belief poses a dilemma that questions existing traditions); and narratives (perhaps the best-known narrative in British governance is the Westminster Model—a longstanding member of ‘the Australian family of governmental traditions’ but not an administrative tradition). The authors define a tradition as ‘a set of understandings someone receives during socialization’ and, more pertinently in this context, a ‘governmental tradition’ as ‘a set of inherited beliefs about the institutions and history of government’. They caution against attributing too much importance to the influence of traditions but conversely question the scant attention given to it by scholars of public administration and political science. The authors’ focus is mixed, moving back and forth between the need to take account of ‘governmental’ and ‘administrative’ traditions. Notwithstanding this approach, they put forward a sound case for pursuing study based on both forms of ‘tradition’ in academic public administration research. They themselves recognise this dualism and the potential pitfalls it presents. Accordingly, they use the term ‘governance’ to describe analysis based on traditions: We use governance as our preferred shorthand phrase for encapsulating the changing form and role of the state … a key facet of these changes is public sector reform … The point is to identify the different ways in which recent changes are constructed and see if we can place these constructions in long-standing but continuously evolving traditions (pp. 13, 14). At the time of writing, Mark Bevir was an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley; R. A. W. Rhodes and Patrick Weller were Professors of Political Science at The Australian National University and Griffith University, respectively. Alan R. Nankervis, Fang Lee Cooke, Samir R. Chatterjee and Malcolm Warner, New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India, Routledge, Oxford, UK, 2013. Chapter 2, ‘Cultural and Traditional Legacies, Leadership Values and Human Resource Management Principles’, pp. 27–45. This book is a collective enterprise of the four authors, with Professor 3 Chatterjee having primary responsibility for the chapter discussed here (APS Commission Library). The book, of which this chapter forms a part, presents a comprehensive analysis of the similarities and differences between contemporary human resource management systems, processes and practices in two increasingly important economic great powers in Asia: China and India. It also sets the subject in its historical, social and cultural contexts. The author stresses the similarities between the key elements of the management systems of these ancient civilisations. The concept and practice of bureaucracy, for example, guided organisational practice in China for thousands of years before Max Weber (1864–1920) popularised it in Europe. Ethical precepts for leadership behaviour advocated by Confucius informed the ideals of the Indian emperor Asoka (or Ashoka) in the third century BC, and the Sreni system of management was widespread in India by 800 BC. This system guided management ideas for centuries before the Roman ‘proto-corporation’ model was established. Indeed, the first known treatise on public management in the world (Arthashastra), was written around 300 BC by ‘the greatest strategic thinker of the time’, Kautilya (also known as Chanakya), who was based at the world’s oldest international university, Taxila. The work set out principles for good governance and encouraged the emergence of complex bureaucratic systems. Chatterjee argues that in order to understand how the Chinese and Indian civil services—and more specifically their human resource management roles—influence governance, knowledge of their structures and administrative traditions is essential. Confucianism, Marxism and Maoism have been key factors in framing Chinese bureaucratic practice; each retains a partial potency in influencing today’s practice despite the reforms of the last thirty years. As the author concludes, ‘… the relevance of the core Confucian values is undeniably a very powerful force in shaping the leadership culture in China. Such ideas have served as a proxy for a legalistic approach and a less adversarial mode of organizational dynamics’ (p. 31). In a classic case of transfer between administrative traditions, the reformist leadership in China has since the late 1970s adopted Western management ideas and adapted them to the local context—‘Chinese characteristics’. In India, British practice from the days of the Raj, for example, the ancient influences already referred to, and post-Independence reform all continue to shape Indian human resource management and wider public administration practice. Under Ashoka, often described as the greatest and most idealistic Indian emperor, democratic and leadership principles were propagated. Pillars emphasising the importance of moral and ethical precepts, behavioural codes and guides to the best managerial and leadership ideals were erected literally across his empire. The Sreni system of management was for centuries the principal form of organisation for the armed services and local government (as well as business) in India. Sreni dharma specified the need for complex organisational structures and detailed rules to guide supervisors, managers and even monarchs. Government leadership appointments were required to be merit-based, with central managerial practices including the use of ‘incentive’ (i.e. performance) pay. Perhaps the most significant feature of the Sreni dharma was its democratic spirit (equity/equal treatment of employees) and its focus on training and development. The Indian cultural (and administrative) traditions were based on: Human Values; Social Values; and Organisational Values, with distinctive and specific tradition-anchored belief systems and leadership emphases rooted in each. Chinese scholars in many cases spent decades at Indian places of learning, taking back to China selected principles and practices which were later incorporated into Chinese bureaucratic practice. The task of tracing these influences—how those of China shaped India’s bureaucratic practice and vice versa—and over so many centuries, as well as the influences of later developments such as British rule, is a demanding but worthwhile one. As Chatterjee states, this work ‘… not only 4 reframe[s] discussions about emerging trends in managerial leadership and human resource management models and practices in the two countries, but also the very purpose of management itself’ (p. 35). As a result, he concludes, ‘The embracing of new capacities for engaging in each other’s cultures and traditions may well define how corporate strategies, and in particular HRM practices, may emerge’ (p. 44). Alan R. Nankervis is Adjunct Professor of Human Resource Management at Curtin Business School, Western Australia; Fang Lee Cooke is Professor of Human Resource Management and Chinese Studies at Monash University, Melbourne; Samir R. Chatterjee is a Professor at Curtin Business School; and Malcolm Warner is Professor and Fellow Emeritus at Wolfson College and Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, UK. Martin Painter and B. Guy Peters, ‘Administrative Traditions in Comparative Perspective: Families, Groups and Hybrids’, in M. Painter and B. Guy Peters (eds), Tradition and Public Administration, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK, 2010, pp. 19–30 (APS Commission Library). The authors explore the principal global administrative traditions, whose member-nations share a common administrative inheritance. They are careful to note, however, that such traditions are multidimensional in nature. As a result their list of categories does not follow any rigid ‘classificatory’ logic; rather, each tradition is described in ‘geographical, historical and cultural’ terms. This chapter represents in many respects the culmination of extensive work on this subject (especially that of Martin Painter) going back to 2000. The nine traditions identified are: Anglo-Saxon (or Anglo-American) (main member nations: the UK, Ireland, the USA, Australia, (British) Canada, New Zealand). Defining characteristic: ‘the state’ (as distinct from ‘the government’) is not part of the discourse of law or politics (and rarely appears as a concept in academic writing about public administration). Napoleonic (France, Spain and a number of other Southern European countries). Defining characteristic: the law is utilised by the state as an instrument for intervening in society rather than serving as a means for resolving conflict between social actors— administration is closely bound to the law. Germanic (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands). Defining characteristic: a strong and all-encompassing body of public law governs every administrative sphere— the prime example of a ‘statist’ view of governance. Scandinavian (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland). Defining characteristic (but there are notable variations between them): The so-called ‘Nordic variant’, while similar to the Germanic tradition, is more firmly rooted in a ‘social compact’ arising from a deep-seated democratic and communitarian tradition—hence the strong state-welfare orientation in these countries. Latin American (the majority of the nation-states of Latin and Central America). Defining characteristic: derived from Spanish and Portuguese colonisation of these countries is their heavy reliance on hierarchy and elaborate systems of law and rules, though with independence in the nineteenth century many of these nations looked to other models such as that of the Napoleonic state. In fact, a local variant of the latter emerged: excessive legalism and formalism on the surface combined with wide latitude for administrators to deploy their discretion as they saw fit. Postcolonial South Asian and African. The authors recognise the apparent oddness of considering together the nations of South Asia and Africa, particularly given the fact that South Asia has a distinct, ancient tradition of indigenous administration and imperial 5 rule. However, they argue that the administrative structures and practices imposed on nations and reimposed on others justifies their inclusion in this category. For example, the district administration system developed by the British to support their rule of India was adapted for ‘subsequent reexport’ to Malaysia, Uganda, Hong Kong and elsewhere. Understanding the public services of these specific countries would therefore require knowledge of how their structures and practices had been developed elsewhere in colonial times and subsequently modified. East Asian. Traditions at work in the principal East Asian nations have been shaped greatly by the religion of each country and the degree of colonisation which has produced ‘a complex process of layering’ in this context. The authors admit that the ‘diverse combinations of local traditions and foreign imports’ lead to ‘a bewildering variety of permutations’, but they identify two factors as key to understanding a nation’s administrative workings: the imperial power which colonised it; and the influence on it of East Asia’s own dominant administrative tradition, Confucianism. Soviet. The Soviet administrative tradition combined one-party rule with a unitary bureaucratic state; it was adopted elsewhere (e.g. the People’s Republic of China, Vietnam and Cuba), though its legacy in the post-communist states of Eastern and Central Europe is ambiguous and difficult to measure accurately. Islamic (Defining characteristic: it stresses the role of a hierarchical, centralised state, with the bureaucracy often central to political rule. But it generally does not exist as the predominant element in a country’s administration; for example, administration in Bangladesh and Malaysia is a mixture of some Islamic elements, components of Asian administrative traditions and elements inherited from British colonial administration). Martin Painter is Professor of Public Administration at the City University of Hong Kong; B. Guy Peters is Maurice Falk Professor of Government at the University of Pittsburgh, USA. Martin Painter and B. Guy Peters, ‘The Analysis of Administrative Traditions’, in M. Painter and B. Guy Peters (eds), Tradition and Public Administration, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK, 2010, pp. 3–16 (APS Commission Library). Painter and Peters establish a place for the study of administrative history and practice in understanding public sector developments and reform. In doing so, they explore the interaction of traditions, politics and external circumstances in shaping public administration. They begin by acknowledging the challenges involved in this branch of comparative public administration but argue that the enterprise is a valuable one. They see administrative traditions as being composed of both ideas and structures and define a tradition as ‘a more or less enduring pattern in the style and substance of public administration in a particular country or group of countries’ (p. 6). They add that traditions live through both the thoughts and actions of practitioners and scholars (‘actors’) and are carried on (and constrained to varying degrees) by inherited structures. The authors go on to specify the variables that define traditions and the ways in which these variables affect public administration. They identify four such variables among the many that might be used. An example in each category and how consideration of it could assist in understanding how a tradition shapes bureaucratic behaviour in a nation is set out below: Relationships with Society: In some Islamic nations the state is in essence subordinate to society because of the theocratic nature of these regimes (e.g. Iran). In such cases the strength and balance between the state and the theocracy influence governance considerably. 6 Relationships with Political Institutions: While the Anglo-American tradition assumes the overriding advantages of a complete separation between politics and administration, in the Germanic model the upper echelons of the public service have clear political allegiances. Law vs Management: In some administrative traditions the public servant is seen primarily as a legal figure enjoying the requisite powers and protections attaching to such an office; in others his/her responsibility is regarded as encompassing management, execution of policy or delivery of services—albeit within a legal framework. Accountability: Although all political systems embed the conception of accountability into their structures and practice, this can differ considerably between jurisdictions. In some nations, law is seen as the main mechanism for controlling bureaucracy (e.g. administrative courts within the public service itself). The chief alternative to the legalistic form of accountability is to rely on political entities, especially parliament. The authors offer four reasons for analysing administrative traditions in attempting to provide an answer to ‘the central puzzle’ of this subject: ‘the extent to which a concept of administrative tradition can help account for change’. Briefly, these are: 1) Jurisdictional (and historical) work is an invaluable tool for comparative analysis; 2) This activity assists in assessing the likelihood of reform success; 3) Traditions work helps considerably in evaluating the strengths of respective governance and bureaucratic systems (e.g. Anglo-Saxon vs Continental); and 4) Such analysis enables public servants and academics to look at their own traditions and ways of working through different lenses. Martin Painter is Professor of Public Administration at the City University of Hong Kong; B. Guy Peters is Maurice Falk Professor of Government at the University of Pittsburgh, USA. Kutsal Yesilkagit, ‘The Future of Administrative Tradition: Tradition as Ideas and Structure’, in M. Painter and B. Guy Peters, Tradition and Public Administration, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK, 2010, pp. 145–157 (APS Commission Library). The author discusses the impact of the traditions approach in driving and interpreting contemporary public administration reform. In doing so, he poses and provides answers to four questions: 1) When and under what conditions do national policymakers implement public sector reforms? 2) Why do some countries’ national policymakers implement certain reforms earlier than others? 3) Why do certain countries never implement a specific reform at all? 4) If a similar reform is implemented in a range of countries, why does the outcome of the implementation vary across these countries? From a comparative perspective, he concludes, the interesting question is not when an administrative system but how much later another administrative system undergoes reform. To which could be added the consideration: why in some instances does reform not occur at all? Yesilkagit argues that in answering these key questions the factor of administrative tradition must take a prominent place. Whether it is seen as consisting primarily of ‘historical legacies’, ‘administrative culture’ or a combination of enduring ‘cultural’ and ‘institutional’ considerations, it must be included in public administration analysis. The author asserts that it plays a central role in filtering and adapting new reforms to the local context or enabling administrative systems to resist new reforms. Yesilkagit stresses, too, that the term administrative tradition can refer to both ideas and beliefs about public administration as well as the structure of administration. Therefore, in the interests of methodological clarity, he frames his analysis in terms of these two analytically independent attributes. 7 However, while arguing for the importance of the administrative tradition approach, Yesilkagit is careful to stress that it should be considered as one of a number of factors in explaining the course of public sector events and change. It is ‘one of the several partial determinants of reform’ to be examined along with political, economic, demographic and situational variables which also exert pressure on the processes and outcomes of reform. Accordingly, he concludes, in order to fully appreciate the weight of administrative tradition in explaining change it is necessary to understand how an administrative tradition is connected to these other variables as well. Other elements in play at the respective levels of government (i.e. international, national, regional, local) also influence the potential of the tradition to shape change. Kutsal Yesilkagit is an Associate Professor in the School of Governance at the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands. 8