Information

advertisement

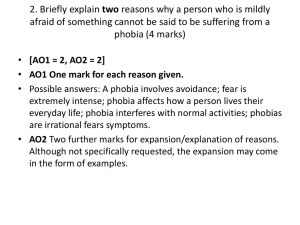

Treatments of Dysfunctional Behaviour The Theories/Studies 1. McGrath (1990) – Successful Treatment of a Noise Phobia 2. Leibowitz (1988) -Treatment of Social Phobia with Phenelenzine 3. Ost & Westling (1995) -Treatments for panic attacks There many treatments for dysfunctional behaviour from all of the approaches however, the three treatments covered in this section reflect the three approaches examined in the explanation of dysfunctional behaviour section. This section therefore, looks at the cognitive, biological and approaches and the behaviourist perspective to treating dysfunctional behaviour. 1. McGrath (1990) – Successful Treatment of a Noise Phobia: Behavioural Background: Behaviour is learnt and has little to do with the individual but instead the situation they are in. Classical conditioning theory, look at previous notes. Aim: To treat a girl with specific noise phobias using systematic desensitisation. Approach/Perspective : Behavioural Type of Data: Method: A case study that details the treatment of a noise phobia in one girl. A single participant design. Details: A nine-year-old girl called Lucy, who had a fear of sudden loud noises, including: balloons, party poppers, guns, cars backfiring and fireworks. . She had lower than average IQ, and was not depressed, anxious or fearful (tested with psychometric tests), so only had one specific phobia. Lucy was brought to the therapy session and told what would happen. Her parents gave consent for further sessions. At the first session, Lucy constructed a hierarchy of feared noises. Lucy was taught breathing and imagery to relax, and was told to imagine herself at home on her bed with her toys. She also had a hypothetical ‘fear thermometer’ to rate her level of fear from 1-10. As she was given the stimulus of the loud noise, she had paired her feared object (the loud noise) with relaxation, deep breathing and imagining herself at home with her toys. This would naturally lead her to feel calm. She then associated the noise with feeling calm. So after four sessions she had learned to feel calm when they noise was presented. She did not need to imagine herself at home with her toys any more. Results; At the end of the first session, Lucy was reluctant to let balloons be burst. At the end of the first session, Lucy was reluctant to let balloons be burst even at the far end of the corridor. When the therapist burst the balloon anyway Lucy cried and had to be taken away. She was encouraged to breathe deeply and relax. By the end of the fourth session, Lucy was able to signal a balloon to be burst 10 metres away. , with only mild anxiety. On the fifth session, Lucy was able to pop the balloons herself. Over the next three sessions, Lucy was able to pull a party popper if the therapist held it. By the tenth and final session, Lucy’s fear thermometer scores had gone from 7/10 to 3/10 for balloon popping, from 9/10 to 3/10 for party poppers and from 8/10 to 5/10 for the cap gun. Conclusions: It appears that noise phobias in children are amenable to systematic desensitisation The important factors appear to have been giving Lucy control to say when and where the noises were made, and the use of inhibitors of the fear response, which included relaxation, conservation and a playful environment 2.Leibowitz (1988) - Treatment of Social Phobia with Phenelenzine: Biological Background: Biological treatments are often the first treatments offered for dysfunctional behaviour, often because diagnosis is made by medical practitioner and the medical approach supports the use of drug therapy. One of the benefits of psychopharmocotherapy is the speed of the effects, some drugs almost instantaneous results. However, other therapies are now used to supplement the biological therapy such as cognitive which can bring about longer lasting change and without the side effects that drug therapy may incur. Aim: To see if the drug phenelzine can help treat patients with social phobia. Approach/Perspective : Biological Method: A controlled experiment where patients were allocated to one of three conditions, and treated over eight weeks. They were assessed for social phobia on several tests such as Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety and the Liebowitz Social Phobia Scale. This had common manifestations of social phobia and patents rated 1–4 for the fear produced and 1–4 for the steps taken to avoid the phobic situation. Details: An independent design with patients being allocated randomly to one of four groups. One group was treated with phenelzine, and one given a matching placebo. A second treatment group was given atenolol and another placebo group was given a matching placebo. 80 patients meeting DSM criteria for social phobia aged 18–50 years. They were medically healthy and had not received phenelzine for at least two weeks before the trial. Each was assessed to see that there were no other disorders and each signed a consent form before the research. Patients were assessed at the beginning, and then given their drug or placebo, with gradual increases in dosage of phenelzine or atenolol in the treatment groups. Each patient was then reassessed on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety and the Liebowitz Social Phobia Scale. Independent evaluators were used to carry out clinical assessments in a double blind situation. Results; After eight weeks significant differences were noted for the phenelzine groups, with better scores on the tests for anxiety compared to the placebo groups. There was no significant difference between the patients taking atenolol and those taking a placebo Conclusions: Phenelzine but not atenolol is effective in treating social phobia after eight weeks of treatment. 3.Ost & Westling (1995) - Treatments for Panic Attacks: Cognitive Background: Cognitive Behavioural uses cognitive approach to restructure thoughts as well as behaviourism (relaxation) the way the person behaves. Does not look at the Cause but focuses on the present symptoms. How the person thinks about an event and its effect on what they did. If negative thought can be reinterpreted then the person will feel better and the behaviour will change. Aim: To compare cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) with applied relaxation as therapies for panic disorder. Approach/Perspective Cognitive Method: A longitudinal study with patients undergoing therapy for panic disorder. Independent design experiment with participants randomly allocated to one of two conditions, cognitive or drug therapy. The patients with DSM diagnosis of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. Recruited through referrals from psychiatrists and newspaper advertisements. 26 females and 12 males, mean age 32.6 years (range 23–45 years). From a variety of occupations and some married, some single and some divorced 38 patients were diagnosed with moderate to severe depression were assessed using Beck’s Depression Inventory and two other rating scales. Details: Pre-treatment: baseline assessments of panic attack, using a variety of questionnaires (e.g. the Panic Attack Scale, Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire, etc.) Patients recorded details of every panic attack in a diary. Each patient was then given 12 weeks of treatment (50–60 minutes per week), with homework to carry out between appointments. Applied relaxation was used to identify what caused panic attacks, and then relaxation training started with tension-release of muscles. This was gradually increased so that by session 8 rapid relaxation was used and patients were able to practise their techniques in stressful situations. CBT was used to first identify the misinterpretation of physical symptoms and then to generate an alternative cognition in response. For example, not to feel panic when something stressful happened, but to come up with an alternative explanation (e.g. my heart racing is not a heart attack but a normal physical reaction to stress and it will slow down in a minute). This was then tested in situations where participants had panic situations induced, but were not allowed to avoid them, so that eventually they had to accept that their restructured thoughts were right. Patients were then reassessed on the questionnaires. After one year a follow up assessment using the questionnaires was carried out. The therapy session were prescribed and controlled and observed to ensure reliability. Results; Applied relaxation showed 65% panic-free patients after the treatment, 82% panicfree after one year. CBT showed 74% panic-free patients after the treatment and 89% panic-free after a year. These differences were not significant. Complications such as generalised anxiety and depression were also reduced to within the normal range after one year. Conclusions: Both CBT and applied relaxation worked at reducing panic attacks, but it is difficult to rule out some cognitive changes in the applied relaxation group even though this is not focused on in this research. Summary: Treatments of Dysfunctional Behaviour The treatments of dysfunctional behaviour are not limited to those in this booklet; there are other approaches beyond the specification, such as humanistic client-centred therapy and psychodynamic therapies. Who can forget the case of Little Hans and Freud in the AS course? Within the approaches that have been covered, there are many more treatments, for example there are biological treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy. Similarly there are many therapeutic techniques based on the assumptions of operant conditioning, such as token economies, and on classical conditioning such as flooding, in addition to Mc Grath’s systematic desensitization described here.