Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles?

advertisement

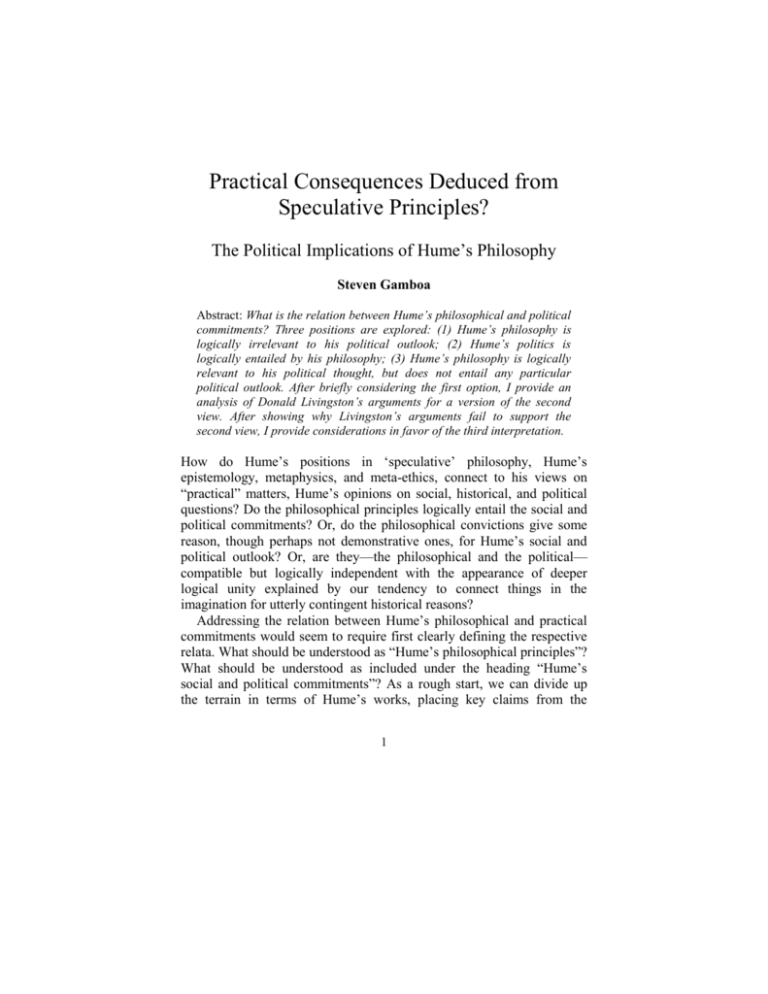

Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles? The Political Implications of Hume’s Philosophy Steven Gamboa Abstract: What is the relation between Hume’s philosophical and political commitments? Three positions are explored: (1) Hume’s philosophy is logically irrelevant to his political outlook; (2) Hume’s politics is logically entailed by his philosophy; (3) Hume’s philosophy is logically relevant to his political thought, but does not entail any particular political outlook. After briefly considering the first option, I provide an analysis of Donald Livingston’s arguments for a version of the second view. After showing why Livingston’s arguments fail to support the second view, I provide considerations in favor of the third interpretation. How do Hume’s positions in ‘speculative’ philosophy, Hume’s epistemology, metaphysics, and meta-ethics, connect to his views on “practical” matters, Hume’s opinions on social, historical, and political questions? Do the philosophical principles logically entail the social and political commitments? Or, do the philosophical convictions give some reason, though perhaps not demonstrative ones, for Hume’s social and political outlook? Or, are they—the philosophical and the political— compatible but logically independent with the appearance of deeper logical unity explained by our tendency to connect things in the imagination for utterly contingent historical reasons? Addressing the relation between Hume’s philosophical and practical commitments would seem to require first clearly defining the respective relata. What should be understood as “Hume’s philosophical principles”? What should be understood as included under the heading “Hume’s social and political commitments”? As a rough start, we can divide up the terrain in terms of Hume’s works, placing key claims from the 1 2 Steven Gamboa Treatise, the two Enquiries, and the Dialogues concerning Natural Religion in the ‘speculative philosophy’ category, while views expressed in the Essays, The History of England, and Hume’s epistolary writings are filed in the ‘practical social-historical-political’ category. This strategy does nothing to alleviate the many controversies and disputes among Hume’s readers concerning the correct interpretation of both the philosophy and the politics. On the philosophy side, we find interpretations of Hume’s main philosophical aims and methods that emphasize competing verificationist, realist, empiricist, skeptical, and naturalist themes in various combinations. On the political side, there has been even less consensus, both in Hume’s day and our own. In his own time, Hume’s political allegiances were viewed with suspicion by both Whigs and Tories. Thomas Jefferson famously had Hume’s History banned from the University of Virginia because of what he perceived as its pernicious Tory biases, but Hume’s antipathy towards established religion and lack of piety, as well as his general skepticism, made him unacceptable to died-in-the-wool Tories such as Samuel Johnson. Hume’s oft quoted remark, “My views of things are more conformable to Whig principles; my representations of persons to Tory prejudices,”1 did little to allay the suspicions about his politics. Contemporary scholarship has offered up a diversity of readings of Hume’s politics, ranging from staunchly conservative to progressive liberal and many shades in between. Everyone acknowledges that these labels are anachronistic when applied to Hume and his 18th century context, but I do not think it is wrong to expect that a philosophically informed political outlook (assuming that Hume had one) should be relevant to political issues framed in terms of categories different from those of its own specific historical context (though clearly it would be a mistake to demand that Hume fit into one or another contemporary category without remainder). It is not necessary to settle these interpretive disputes before the main question of this essay can be addressed. In fact, the hope is that examining the links between Hume’s philosophical and political commitments can provide some new leverage for addressing longstanding debates within both domains of interpretation. The interpretive options can be grouped into three categories: on one view, Hume’s philosophical commitments carry no logical implications for Hume’s 1 . E. C. Mossner, The Life of David Hume (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980), 311. Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 3 politics; on a second view, there are clear logical and conceptual entailments between Hume’s philosophical principles and a well-defined, articulated political standpoint; on a third (intermediate) view, there are implications for how we should think and converse about political life from Hume’s philosophy, but these implications do not provide a normative grounding for any particular view about the best political and social order. Advocates of the first view might argue that, just as no one seriously expects to find logical or conceptual entailments between someone’s theoretical commitments in physics, chemistry, or mathematics and her political outlook,2 one should not look to discover political implications from someone’s metaphysical and epistemological commitments. On this view, technical philosophy and politics are as much non-overlapping domains as algebra and ornithology. Despite a shared rationalist epistemology, Descartes was a reactionary royal absolutist, and Spinoza, a radical republican. Many have held that there is a logical or conceptual link between empiricism and political liberalism. But perhaps the appearance of logical relevance is, as David Miller puts it, “best explained by the historical fact that certain philosophies have emerged at the same time as their (seemingly) associated ideologies.”3 As with the rationalists Descartes and Spinoza, the shared empiricism of Neurath and Quine clearly did not entail a common political outlook. With respect to Hume’s case, the view advises against expecting to find support for Hume’s political conclusions in his philosophical premises. The view that Hume’s strictly philosophical commitments are irrelevant to his opinions on political matters has been endorsed by a number of prominent figures. Bertrand Russell cited Hume and himself as examples to show the absence of any necessary connection between epistemological and political views: while they agreed on abstract philosophical matters, they disagreed completely in their politics.4 2 . The consensus assumed here is mainly for rhetorical purposes. For an example of the complex interconnections between science/mathematics and politics in the early 18th century, see Stephen Shapin’s “Of Gods and Kings: Natural Philosophy and Politics in the Leibniz-Clarke Disputes,” Isis 72, no. 2 (June 1981): 187-215. 3 . David Miller, Philosophy and Ideology in Hume’s Political Thought (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), vii. 4 . See Bertrand Russell, “A Reply to My Critics,” in The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell, ed. Schilpp (Evanston and Chicago, 1944), cited in Miller, Philosophy and Ideology in Hume’s Political Thought, 13. 4 Steven Gamboa Duncan Forbes may also be included among those skeptical of any entailments. In his major work on Hume’s political thought, Hume’s Philosophical Politics, Forbes uses the term “philosophical” mainly in the sense of being disinterested and non-partisan, and thus seems to deny (at least implicitly) any deeper logical connections between the theoretical side of Hume’s philosophy and his political views.5 Hume’s remarks in section I of the Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding seem to lend support to the ‘no-entailment’ view. Hume writes that The abstruse philosophy, being founded on a turn of mind, which cannot enter into business and action, vanishes when the philosopher leaves the shade, and comes into open day; nor can its principles easily retain any influence over our conduct and behavior.6 If speculative philosophy has little influence on conduct or behavior, it would follow that it can offer no consequences for political life. However, in the remainder of the section, Hume first qualifies, and then reverses, this initial verdict on the relevance of abstract philosophy for practical affairs. First, just as the detailed work of the anatomist is useful to the painter, so the rigors of speculative philosophy may be of benefit to the more practically minded politician by encouraging greater “foresight and subtility” in their reasonings.7 Like a contemporary academic philosopher asked to defend the value of her discipline, Hume here highlights the improvement in critical thinking skills subsequent to the study of philosophy. But beyond improving our reasoning skills, the pursuit of abstract philosophy in the Humean mold offers two services of tremendous importance for practical affairs: one critical, the other positive. First, since it is needed to combat ‘false metaphysics’ and ‘deceitful philosophy’, ‘true philosophy’ provides a philosophical and moral hygienic against superstition and fanaticism that pose serious practical dangers, if left unchecked. Secondly, there is the possibility that philosophy, “if cultivated with care, and encouraged by the attention of the public,” will develop a genuine science of human nature that would . Duncan Forbes, Hume’s Philosophical Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975). 6 David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Tom L. Beauchamp (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), I.3. 7 Ibid., 1.9. 5 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 5 constitute an “addition to our stock of knowledge, in subjects of such unspeakable importance.”8 The view that Hume’s philosophical principles have no relevance for his politics does not appear to have been shared by Hume himself. Contemporary Hume scholarship is much more inclusive in its treatment of all aspects of Hume’s thought than was previously the case— providing a much fuller and richer picture of Hume as philosopher, moralist, historian, and political theorist, developing what might be called a unified ‘Humean outlook’ across a wide range of issues. Stuart Hampshire captured the spirit of much of this work when he remarked that, “it was the application of a true understanding of human nature, with a view to a sane management of human affairs that finally interested Hume, rather than pure philosophy so called.”9 Given these considerations, a view that denies any entailments among these domains should be treated as prima facie unwarranted and avoided unless, and until, attempts to delineate an underlying unity are found to fail. The second view on the relation between Hume’s epistemological and metaphysical principles and his political commitments holds that there are strong entailments between the two domains, such that the former in some sense fix or ground the latter. In his essay “Philosophy and Politics,” Russell maintains that there do exist logical entailments linking various philosophies to political systems, though this position clearly contradicts his earlier pronouncements cited above. With regards to Hume specifically, Russell contends that Hume’s philosophical skepticism was logically related to his Toryism. After setting forth his skeptical conclusions, which, he admits, are not such that men can live by, [Hume] passes on to a piece of practical advice which, if followed, would prevent anyone from reading him. “Carelessness and inattention,” he says, “alone can afford us any remedy. For this reason, I rely entirely upon them.” He does not, in this connection, set forth his reasons for being a Tory, but it is obvious that “carelessness and inattention,” while they may lead to acquiescence in the status quo, cannot, unaided, lead a man to advocate this or that scheme of reform.10 8 Ibid., 1.17. 9 . Cited in David F. Pears, David Hume: A Symposium (London: Macmillan, 1963), 6. 10 . Bertrand Russell, “Philosophy and Politics” in Unpopular Essays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950), 4-5. 6 Steven Gamboa For Russell, Hume’s thorough-going philosophical skepticism leads logically to a reactionary politics. But beyond these broad strokes, Russell offers little support for his generalizations. The Hume scholar who makes the most forceful case for a strong version of the second interpretation is Donald Livingston.11 In his ambitious and wide-ranging work Hume’s Philosophy of Common Life, Livingston argues that Hume’s semantic and epistemological principles are intended to provide a foundation for a ‘doctrine of limits’ beyond which political criticism of the existing social and political order cannot go. Livingston argues that Hume’s aim is to provide political conservatism with a philosophical response against all forms of political radicalism by showing that they are either incoherent or self-defeating. His account of Hume’s political philosophy requires that he discover, in Hume’s thought, the resources to construct conceptual barriers to the possibility of radical critique of the existing social and political order. For Livingston’s Hume, the authority of the existing social-moralpolitical life-world cannot be challenged in any wholesale way without incurring incoherence. This is intended as a logical result, and not a mere matter of prudence and moderation: The conservative character of Hume’s philosophy is often thought of as an appeal to moderation, but that would be a fundamental mistake. Moderation implies an activity that is acceptable. […] Philosophical criticism of common life…is not an acceptable activity. It is logically incoherent and self-deceptive, and one cannot speak of a proper degree of that activity.12 According to Livingston, while it would be a mistake to categorize Hume among the “metaphysical conservatives” who appeal to divine authority to sanction this-worldly social and political arrangements, Hume “does, . Livingston’s take on the deep connections between philosophical first principles and political ideology are not restricted to Hume. In his Philosophical Melancholy and Delirium: Hume’s Pathology of Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), Livingston says “epistemologies have an ideological and rhetorical dimension, and may be viewed as speeches embedded in a culture and addressed to that culture.” Livingston claims that empiricism is “at the service of … a militant ideology, resolutely forward-looking and hostile not only to religious tradition but to all traditions.” ( 5) Given empiricism’s conceptual links to this ideology of progress, it would be best if we resist the pressure of ideological prejudice and not classify Hume as an empiricist at all. 12 . Livingston, Hume’s Philosophy of Common Life, 334. 11 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 7 in his own way, share with them the conviction that established order has a sacred character and that this sacred character constitutes part of the authority of that order.”13 There is a dilemma faced by anyone wishing to argue for the rational authority of the existing social and political order. How can we know that our existing plan, even if brought to its full potential through gradual internal reform, represents anything more than a local optimum in terms of social utility? The suspicion remains that there might be an alternative social and political arrangement that offers a higher utility optimum, perhaps even a global optimum. Unfortunately, such a peak may not be accessible from our current slope; reaching it would require a radical transformation of our social order, an abandonment of our current plan. This possibility is the source of radical hope. Hume was aware that it is impossible to refute such radical hope from purely empirical or historical evidence. His own historical work showed that radical transformations of existing political structures could, and did, make possible improvements in social utilities that would have been impossible under the previously existing regime. Hume’s treatment of the Puritan rebellion in the English civil war is enlightening in this regard. That he considered the members of the Puritan party fanatics consumed by metaphysical fancy is clear from a casual reading of the first (published) volume of his History of England. Yet, despite his distrust of Puritan fanaticism, Hume concedes that “the new plan of liberty,” which made Britain’s mode of governance the envy of the cultured world, was made possible only by that very fanaticism. So absolute, indeed, was the authority of the crown, that the precious spark of liberty had been kindled, and was preserved, by the puritans alone; and it was to this sect, whose principles appear so frivolous and habits so ridiculous, that the English owe the whole freedom of their constitution.14 Hume’s honesty in assigning credit attests to his integrity as a historian, but it does leave our understanding of the Puritans in a curious state: on the one hand, their religious fanaticism must be regarded as subversive of any kind of political order; but on the other hand, in pursuing their 13 . Ibid., 330. . David Hume, The History of England from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the 14 Revolution of 1688, 6 vols. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1983), vol. 5: 183. 8 Steven Gamboa fanatical objectives, they struck the spark that ignited the flame of liberty. J. G. A. Pocock captures this point: “The great originality of [Hume’s] history of the Puritan Revolution is his insistence that the fanaticism of the Puritan sect was both an excessive threat to rational freedom and a necessary step towards its establishment.”15 Hume’s account of the Puritan episode makes it plain that no purely historical argument could serve to abolish radical hope in a future, more perfect social and political order. These considerations lead to the dilemma mentioned above: the conservative can either dogmatically reject any change to the status quo, or accept that radical schemes are in principal coherent, and present possible vehicles for social improvement. If I understand him correctly, Livingston’s idea is to use Humean resources to resolve this dilemma for conservatism. In Livingston’s view, Hume does not merely say that radical designs are impractical or fraught with dangers (empirical claims all), but that they are, in principle, incoherent and self-defeating when they engage in a wholesale critique of the “sacred” norms of the existing moral world.16 Demonstrating the incoherence and self-defeating nature of radical projects is what Livingston means by providing “conceptual barriers” to radicalism. If Livingston’s project were successful, it would establish entailments of the strongest logical sort between Hume’s philosophical principles and a fully articulated normative political position. Critical response to Livingston’s work, since he developed these views in the mid-1980s and 1990s, has generally acknowledged its bold originality and insight, but most critics have not been persuaded to accept his more dramatic conclusions.17i Yet, despite Livingston’s prominence among contemporary Hume scholars, there has been no detailed attention to the key arguments he offers to support his interpretation. Dissenting critics have cited textual evidence that seems to tell against Livingston’s bold . J. G. A. Pocock, “Hume and the American Revolution: The Dying Thoughts of a North Briton,” in McGill Hume Studies (San Diego: Austin Hills Press, 1976), 338. 16 . Livingston’s use of the term “moral world” should not be construed as referring to the realm of value per se. Rather, he uses the term to refer to the world of relationships and roles constitutive of a social community understood in the broadest sense (often invoking both Heideggerian and Wittgensteinian tropes). 17 . For critical reception of Livingston’s interpretation, see reviews by John Deigh, Ethics 95, no. 4 (July 1985): 959-960; David Fate Norton, Journal of the History of Philosophy 25, no. 2, (1987): 300-302; Peter S. Fosl, Hume Studies XXIV, no. 2, (November 1988): 355-366; and Marina Frasca-Spada, Mind 110, no. 439 (2001): 783-789. 15 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 9 interpretation, and in favor of their more moderate views, but Livingston’s case for his interpretation deserves consideration in its own right. Livingston is not only offering a novel interpretation of Hume’s thought, but trying to show how certain putatively Humean political positions can be derived from Hume’s philosophical principles. To give such an effort its due requires that, beyond contesting its conclusions, we show where the arguments go wrong. The exercise should also prove helpful in deciding whether any version of the strong entailment view is viable, and if not, what a better understanding of the relation between Hume’s philosophy and politics would look like. In Livingston’s account, Humean conservatism confronts three philosophically or religiously inspired radical challengers: (1) Metaphysical Radicalism; (2) Sacred Providential Radicalism; and (3) Secular Providential Radicalism. Metaphysical radicals hold that the standards governing existing social and political institutions are false until they can be shown to be in accord with intuitively certain propositions. The actual, historically determined social order is judged according to atemporal, abstract standards derived from self-evident axioms. Both types of providential radicalism, sacred and secular, differ from metaphysical radicalism in that they are historically based. Unlike the metaphysically inclined, the providential radical finds the standards for critique of existing social and political arrangements, not in some abstract, atemporal, rational order, but in the historical process itself. In this respect, both varieties of providential political theory share with Livingston’s brand of Humean conservatism the view that normative standards are always derived from an understanding of temporally determined concepts. According to Livingston, however, there is a fundamental difference between providential theories and Humean conservatism: the conservative explicates historical standards as a relation between the normative past and the present, whereas providentialists explain historical standards as a relation between a normative future and the present. For Livingston, the providential framework disposes one to criticize the present in terms of total revolution, rather than one of reform: 10 Steven Gamboa The belief that there is a higher stage on the way enables one to launch into radical destruction of the present with confidence; any excess or mistakes will be, as it were, self-corrected in the next stage [of history].18 For Livingston, the connection between providential theories and social radicalism is clear. Sacred and secular versions of providential theory are differentiated once we ask how knowledge of the future state is supposedly acquired. For the sacred providentialist, social and political knowledge is a form of eschatology based on God’s revelation in history. Secular providential theory accounts for our knowledge of the future by reference to purely secular laws of history. For Livingston, secular providential theory contains “the same destiny-laden modality of the sacred version, the only difference being that the historical process itself takes the place of God’s acts in history.”19 There are plenty of 18th century examples of sacred providentialists, such as Richard Price and Catherine Macaulay. Advocates of secular providential political theory in Hume’s time are much more scarce— Livingston cites the French philosophe Turgot, with his confidence that all history is the history of progress, as someone of Hume’s acquaintance who conceivably represented this attitude. Clearly Marx provides the paradigm of secular providentialism, and the fact that secular providential political theory is such a markedly 19th century conceptual development presents problems for Livingston’s interpretation of Hume. While I believe Livingston succeeds in developing genuinely Humean arguments against both the metaphysical and sacred providential versions of political radicalism, his attempt to extend these arguments to encompass secular radicalism fails. Of Livingston’s two supposedly Humean arguments against the possibility of secular or naturalistic radical critique, the first is fallacious, and the second is incompatible with fundamental commitments of Hume’s philosophy. In his first supposedly Humean argument against secular radicalism Livingston contends that, since only the past can be normative and constitutive of the moral world, theories that posit a normative future are conceptually incoherent. The following is my reconstruction of his argument: . Livingston, Hume’s Philosophy of Common Life, 298. . Ibid., 292. 18 19 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 11 1. If there were no past existences, the present moral world could not exist. 2. If there were no future existences, the present moral world would remain just as it is. 3. So, the existence of a future is not a necessary condition for the existence of a moral world. 4. If a future is not a necessary condition for the moral world, then the moral world could exist without a future. 5. So, the future, unlike the past, contains no moral entities or values that structure the moral world. 6. If the future contains no moral entities or values, it cannot be used to make rational criticisms of the present social and political order. 7. So, secular providential theory of any sort is impossible. Why does Livingston think that the moral world could not exist if there were no past? The moral world is populated with existences, like senators, fathers, priests, and police officers, which are “past-entailing,” meaning that their existence entails the existence of a past. These existences are defined by concepts that have past-entailing truth conditions. Take the concept ‘priest’. According to Livingston, the application conditions for the predicate “X is a priest” include that “(1) X is a man and (2) that certain propositions about the past are true (e.g., that, among other things, x was confirmed by a bishop in the apostolic tradition).”20 Livingston argues that, though condition (1) is tenseless, the statements that make up condition (2) are irreducibly tensed. Since pasttense expressions cannot be reduced to tenseless expressions, and concepts such as ‘priest’ have past-tense expressions as part of their content, they are past-entailing (true only if there is a past). Thus, the moral world entities such concepts describe exist only if there is a past. A world with no past could have no past entailing existences, i.e., no husbands, wives, judges, civil rights, etc. With regards to the future, however, Livingston contends that the moral world is absolutely independent. Livingston argues that, even if there were no future, what exists now in the moral world would remain unaltered. But if only the future were cut away—if, for instance, the world should end in one hour—the past entailing existences of the normative present 20 . Ibid., 102. 12 Steven Gamboa would remain just as they are. Our hopes and anticipations would be without ontological foundation, but our understanding of what exists in the present world would be unchanged. Presidents, Rembrandts, and friends would be, logically, just as they are now. 21 The considerations Livingston offers for the irreducibility of past-tense expressions to tenseless expressions works just as well for the irreducibility of future tense expressions, so the reason that the future is not necessary for the present moral world must be that the moral world has no future-entailing existences. Future-referring ideas such as “is the heir apparent,” and “is a mother-tobe” can be applied to the present independently of the future. There is no contradiction in saying that someone is the heir apparent but will never become king. But there would be a contradiction in saying that someone is now a senator and that he has no past.22 Livingston’s use of the term “apparent” in the expression “is the heir apparent” gives some insight into the fallacy present in this argument. He equivocates between the truth conditions for a proposition and the epistemic criteria under which accepting a proposition is justified. When he claims that past-entailing propositions entail the existence of the past, he is making a claim about the truth conditions of such propositions. That’s why he can say that, if the world had been created five minutes ago with everything, including everyone’s beliefs, exactly as they are now, the proposition “X was confirmed by a bishop in the apostolic tradition” (which is entailed by someone being a priest) would be false— even if everyone believed it—because the past did not exist. Yet, when Livingston switches to future-entailing concepts, he changes the rules of the game. When we cut away the future, it is no longer the truth conditions for future-entailing concepts that matter, but only our understanding of such concepts. Consider the truly future-referring idea from the previous passage: “… is a mother-to-be” (“heir apparent” is not a future referring idea—“apparent” refers to how things seem now). The proposition “X is a mother-to-be” is true iff x is a mother in the future. If there were no future, saying of a pregnant woman that she is a mother-tobe would be false, for in a futureless world, she will never become a 21 . Ibid., 302-303. . Ibid., 303. 22 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 13 mother. Of course, it would be perfectly understandable and reasonable for someone to hold this false belief. Given the current pregnancy evidence, and the general ceteris paribus presumption that things will go smoothly, applying the “is a mother-to-be” predicate is rationally justified. It is just not true. To choose an example from Hume’s moral vocabulary, consider the concept of “is in the interest of.” It would be epistemically appropriate for me to think that some action is “in my interest” iff I have solid evidence for believing that it will provide me with utility in the future. If the world ended in five minutes, my belief about what is in my interest remains unchanged in terms of its epistemic respectability, but it is not true for the obvious reason: in a world without a future, nothing is in my interest. Livingston wanted to say that, since our understanding of the present moral world would remain unchanged even if the future did not exist, therefore the future is irrelevant to our moral world. But if our understanding is all that matters, then there is no reason to think that the past is necessary for the moral world either. If the moral world necessitates past existences, then it necessitates future existences as well, and only Livingston’s equivocations between metaphysical truth conditions and epistemic warranted assertability conditions could obscure such a fact. In his second purportedly Humean argument, Livingston argues that secular providential radical theories are self-defeating. 1.Secular providential theory attempts to evaluate the present social and political order with providential narrative propositions. 2.Providential narrative propositions are truth-functional conjunctions of present-tense and future-tense propositions. 3.So, secular providential theories are true if and only if future-tense propositions are true. 4.The truth of future-tense propositions entails fatalism. 5.So, secular providential theories entail fatalism. 6.Fatalism is incompatible with human action and freedom. 7.So, secular providential theories, understood as programs for radical political action, are self-defeating. The crucial idea in this argument is premise 4. According to Livingston, belief in determinate truth-values for future-tense propositions implies a view in which future events are “thought of as, in some sense, already having happened and in the light of which our 14 Steven Gamboa present is seen as a passing phase of a process.”23 Livingston contends that fatalism can only be avoided by holding that future-tense propositions have an indeterminate truth-value, but in that case secular providential theories cannot be true. Either way, plans for radical social and political transformation are undermined. Debate over the “problem of future contingencies” has a long pedigree, running from Aristotle’s famous sea battle in De Interpretatione IX to present day battles between proponents of multivalued logics and adherents to bivalence. One might say that Livingston has made a serious mistake to rest his argument on such a contentious premise, and let it rest at that. However, if the premise were one that Hume would accept, i.e., one entailed by genuine Humean principles, then its controversial status would not matter. So if the claim that “the truth of future tense propositions entails fatalism” were one Hume would endorse, then the fact that lots of other folks disagree with it would be irrelevant for our purposes. Unfortunately for Livingston, this premise is incompatible with Hume’s epistemological principles. Why would anyone believe that the truth of future-tense propositions entails fatalism? The basic idea seems to be the following: if every future tense sentence must be either true or false, then, of each pair consisting of a future tense sentence and its denial, one must be true, the other must be false. The inference moves from a commitment to bivalence for a future tense proposition S, (S S), to the claim that either S must be true or S must be false, (S S). In other words, no matter what happens, it happens of necessity, and there’s nothing we, or anyone else, can do about it, i.e., fatalism. To avoid fatalism and salvage the contingency of the future, we are encouraged to reject determinate truthvalues for future tense propositions. What are we to make of this argument in the light of an examination of the links between Hume’s epistemological principles and his political views? Many philosophers, such as Susan Haack24, contend that the inference is guilty of a clear modal fallacy. While it is true that necessarily if the proposition S is true, then S, i.e., (S S), it is not true that if the proposition S is true, then necessarily S, i.e., (S S). The fallacy Haack identifies involves slipping from true claims about logical necessity to false claims about metaphysical necessity. Haack’s 23 . Ibid., 143. . Susan Haack, Philosophy of Logics (Cambridge University Press, 1978), 78. 24 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 15 have not been the last words on future contingencies. Supplementing its premises with certain metaphysical principles regarding natural necessities may salvage the inference. It may be possible to establish its validity in some such manner, but, here, one would surely betray Hume. If Hume’s epistemology de-legitimizes anything, it has to be the notion that we can know any metaphysical necessities concerning matters of fact. Thus, Livingston’s second purportedly Humean argument against secular radicalism is at odds with Hume’s core philosophical commitments. Having dealt with the crucial arguments in support of Livingston’s provocative vision of Hume as philosophical defender of the existing social and political order, we can now better appreciate what is misguided in his interpretation. While offering many insights along the way, Livingston’s interpretation portrays Hume as an ideologically dogmatic conservative committed to the ‘sacred’ status of our present political and social life world. For Livingston’s Hume, the current social and political dispensation is not merely to be given deference on pragmatic and prudential grounds—its strictures and norms must be venerated on philosophical and logical principle. Peter S. Fosl (a former student of Livingston’s) offers the following apt assessment of where Livingston’s interpretation of Hume goes wrong: Livingston is right, of course, to see in Hume a profound respect for custom, habit, and tradition. He is right to see Hume’s criticism of false philosophy and of various political events as animated by his respect for custom and his appreciation of the situatedness of human beings within common life. It is, however, one thing to appreciate and respect tradition. It is quite another to venerate it. The gap between my own position and Livingston’s on this point is the gap between acknowledgment and sanctification, between appreciation and fetishization, between respect and piety. In my own estimation, Livingston’s positive doctrines concerning tradition are not well grounded in Hume’s text—and they are not philosophically tenable.25 Among contemporary Hume scholars, Livingston makes the most sustained effort to go beyond mere generalizations and affinities and to establish clear logical entailments between Hume’s ‘speculative’ . Peter S. Fosl, “Donald W. Livingston’s Philosophical Melancholy and Delirium,” Hume Studies XXIV, no. 2 (November 1988): 355-366. 25 16 Steven Gamboa philosophical commitments and a completely articulated political stance; in that effort, Hume is rendered unrecognizable. This negative result should encourage us to look for less constraining connections between Hume’s speculative and political sides. The third alternative for understanding the relationship between Hume’s philosophical and political writings offers an intermediate view between the ‘no-entailment’ and ‘complete determination’ extremes. The intermediate view expects Hume’s epistemic and metaphysical principles to be rich in implications for how we should think and converse about our shared social and political situation, but these implications are not interpreted as providing a prescriptive grounding for any unique position on what the normatively best political system has to be. In David Miller’s words, the intermediate interpretation claims that “Hume’s philosophy is logically relevant to his political thought without entirely determining its character.”26 Where do Hume’s philosophical convictions have political upshot? The best interpreter of Hume’s thought is Hume himself, and in the passages from the first Enquiry cited above, Hume informs us of two kinds of practical benefits abstract philosophy can afford. First, abstract philosophy provides the resources for effective critique of politically dangerous ‘false philosophy’, or more broadly ideological thought. And secondly, philosophical reflection on human nature can provide the theoretical framework for a genuine science of man and society, a science that we may hope will provide a deeper understanding of the laws that govern human social and political organization. Hume’s social and political thought has a clear critical realist aim: to expose the distortions of ideology that inflame fanaticism and superstition, attitudes which threaten the institutions that make cooperative social life possible and undermine the possibility of future improvements in civil society. We can witness his critical realist approach most directly in his Essays and History of England, where Hume aims to unmask the delusions of both Whig and Tory ideologies regarding the sources of English political legitimacy (the myth of the pre-Norman ‘ancient constitution’ for the former, divine sanction for the latter). In opposition to these explanatory fictions of normativity, Hume’s emphasis, especially in the History, is on the historicity of contingent connections between the motives of historical agents and the outcomes . Miller, Philosophy and Ideology in Hume’s Thought, 14. 26 Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 17 their actions produced. We must learn to acknowledge “the great mixture of accident, which commonly concurs with a small ingredient of wisdom and foresight, in erecting the complicated fabric of the most perfect government.”27 The prominent role Hume ascribes to accumulated chance in producing both the liberty cherished by Whigs and the obedience cherished by Tories effectively sweeps away the philosophical and historical ideologies that made compromise and cooperation between these factions so difficult. Humean critique of ideology is thus meant to have a therapeutic effect on political life: by replacing pursuit of ideological purity with pursuit of real interests, common ground and compromise between competing parties should be easier to find, and partisanship opposition should diminish. The relevance of Hume’s epistemology to the critique of ideology and political wishful thinking is obvious, with special importance going to Hume’s account of testimony in the first Enquiry. While a commitment to critical realism is one implication of Hume’s philosophical principles, clearly no substantive political program, conservative or otherwise, is directly prescribed by this essentially negative, debunking activity. The second source of discernible connections between Hume’s philosophical and political views comes from Hume’s positive contributions to a science of human nature. Specifically, Hume’s naturalistic explanations in both the Treatise (III.ii.2) and the second Enquiry (IV and V) for the emergence of the artificial virtues of justice, respect for property, and the obligation to abide by promises, provide a rich philosophical resource for political thought. The case for a conservative interpretation of Hume’s politics finds support in his account of how our conception of the artificial virtues, such as justice, “arises gradually, and acquires force by a slow progression, and by our repeated experience of the inconveniences of transgressing it.”28 The norms of justice cannot be justified on purely a priori grounds (otherwise the sensible knave would not be possible).29 They gain our approval and acquire motivational efficacy once we experience their benefits in social 27 . Hume, History of England, vol. II. . David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton 28 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000), 3.2.2, para 10. 29 . David Hume, Enquiries Concerning the Human Understanding and Concerning the Principles of Morals, ed. L. A. Selby-Bigge, 2nd ed. (1902; Oxford, 1972), IX.ii, 282283. 18 Steven Gamboa life. Only within the institutions of an existing shared social life, where the norms of cooperative behavior have become internalized in mechanisms of shame and guilt and thus second nature, do the benefits of justice make it rational for us to adhere to its requirements. All this will make us extremely distrustful of any schemes to dismantle or replace existing social institutions. However, Hume’s explanation of the emergence of artificial virtues in his science of human nature also provides fertile material for a much more liberal interpretation of Hume’s political outlook. For Hume, the main challenge for any decent political system is to strike a balance between the needs of social life and the desires of individuals, i.e., between social cohesion and liberty. For Tory traditionalists, order was construed as passive obedience to an ultimately transcendent authority. Political liberalism is in part the idea that we can have political order without subservience to external authority. The main social contract tradition following Hobbes and Locke tries to both explain and justify political authority by showing how it can be established on the basis of rational consent. Hume is famously skeptical both about the coherence of this sort of contractual explanation, and about the ability of reason to play this role on its own. But while Hume disagrees with the standard social contract explanation for the source of our commitment to obey the laws of the state, he does not dispute the essential liberal idea that the political authority of the ruler depends on the opinion of the ruled. According to Hume’s liberal realism, the basis for political order and obedience is explained in a naturalistically plausible way, and without requiring the passive submission to a transcendent authority (even the authority of tradition, pace Livingston). Given that there are strains of what we would consider both conservative and liberal thought in Hume’s science of human nature, what forms of political organization are consistent with Hume’s philosophical principles? The evidence points to a fairly broad and diverse range of political attitudes as, at least, consistent with Humean principle. Staunchly conservative views that reject any systematic meddling with the existing social and political status quo may not be entailed by Hume’s philosophical principles, but they are certainly consistent with them. From the other side of the political spectrum, and Practical Consequences Deduced from Speculative Principles 19 inspired by Hume’s essay “That Politics may be reduced to a Science,”30 Douglass Adair and Duncan Forbes have argued that Humean political theory is best understood as, in Forbes’s words, “constructive, forwardlooking, a programme of modernization, an education for backward looking men.”31 John B. Stewart likewise sees Hume as a dynamic, scientifically-minded transformer of opinion, political practice, and society.32 An important inspiration for Stewart is Hume’s essay “Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth,” where Hume lays out the components of the ideal political constitution. There is debate about how seriously to take Hume’s speculations in this essay, especially since Hume implies that he is among those who “regard such disquisitions both as useless and chimerical,” and provides at best a luke-warm endorsement of his own plan: “Here is a form of government, to which I cannot, in theory, discover any considerable objection.”33 But ironic endorsement or not, the essay does provide further evidence that Hume did not think that radical political projects need be irrational, delusional, or otherwise philosophically suspect. On condition that they are empirically responsible (in other words, non-dogmatic, tentative, open to revision), and also grounded in social and historical reality, then even political views that advocate radical transformations to our current plan are consistent with Hume’s core philosophical principles. Hume’s epistemic commitments have implications for his views on how we should think about politics and our political institutions, but these commitments are not intended to provide a normative prescription for any specific political platform, and are, indeed, consistent with a wide range of diverse political attitude. 30 . David Hume, Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, ed. Eugene F. Miller (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1985). 31 . Douglass Adair, “‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science’: David Hume, James Madison, and the Tenth Federalist,” Huntington Library Quarterly 20, no. 4, (August 1957): 343-360; Duncan Forbes, “Hume’s Science of Politics,” in The Bicentenary Papers from the Edinburgh Hume Conference, ed. C. Morice (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1977), 39-50. 32 . John B. Stewart, Opinion and Reform in Hume’s Political Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992). 33 . Hume, “Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth,” in Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, II.XVI.6.