Paper - CBSM Workshop Papers

advertisement

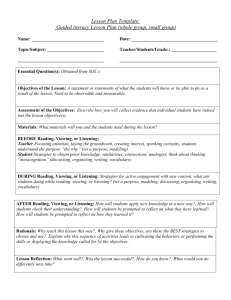

MOBILIZING PROTEST: THE INFLUENCE OF ORGANIZERS ON WHO PARTICIPATES AND WHY Part of dissertation, to be discussed at CBSM Workshop, 2011, Las Vegas Marije Boekkooi Assistant professor Department of Sociology, VU University, Amsterdam M.E.Boekkooi@vu.nl 1|Page INTRODUCTION In this dissertation the focus is on organizers and participants of protest events and the structures that connect them. For protest to occur, someone needs to take the initiative to start organizing and mobilizing for the event. A ‘critical mass’ of people is needed, who are especially motivated, resourceful and willing to put in their time, energy and resources to assume the start up costs of the collective action so that others can easily join (Oliver, Marwell, and Teixeira 1985). The first step of protest is thus the emergence of an initiator who starts assembling a mobilizing structure. This newly formed structure may take any shape from the most formal coalition, to the most informal collection of social networks. This raises the first question to be studied in this dissertation: How do organizers of protest events shape the mobilizing structure (see Figure 1, arrow 1)? FIGURE 1: RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN ORGANIZERS, MOBILIZING STRUCTURE AND PARTICIPANTS MOBILIZING STRUCTURES Coalition MESO Coordination structure Networks SOLID LIQUID 1. MICRO ORGANIZERS 2. PARTICIPANTS When the new structure is assembled, the organizers involved need to cooperate and negotiate together to formulate a campaign plan and set up a campaign. Subsequently, the campaign plan needs to be executed thereby mobilizing participants for the protest event. This raises the second question: How does the shape of the mobilizing structure impact on the actions and motivations of the participants of the protest event (see Figure 1, arrow 2). It has been shown time and again that mobilizing structures impact on who is mobilized. However, which traits of these structures impact on what is still largely unclear (Diani 2004). The exact impact of different mobilizing strategies, the direct impact –thus- of the organizers, has rarely been studied in detail. I will do just that. I will first show that different mobilizing channels reach different and -more importantly- differently embedded people and I will show that different organizers set in motion different mobilizing sequences. And second, I will show that mobilizing strategies also impact on motivations to participate. 2|Page Taken together I thus aim to show how the organizers of a protest event, influence the composition of the demonstration crowd and the motivations of the participants, as their actions and decisions impact on the ‘mobilizing structure’ of the campaign. Who starts organizing and mobilizing and how they do so, shapes the mobilization campaign, which –I propose - has important implications for who will participate and for why. THEORY I expect that initiators of a protest event will start building their mobilizing structure by trying to recruit their strong ties, that is their own submerged networks. Those organizers mobilized in this way, can in their turn start using their strong ties to mobilize their own networks. But to reach beyond their own networks, weak ties are necessary. Often cheap activist channels will suffice to inform a wider circle of organizers who may then enroll themselves to the structure. These channels can reach a wider audience, but not a completely new one. To reach new and unconnected organizers, ‘open channels’ such as the mass media are necessary. Although theoretically initiators may use such channels to recruit new organizers, due to the costs involved it is not likely that they will do so. The mobilizing structure is therefore expected to reflect the initiators networks. Existing networks thus impact on who is recruited. What type of structure these organizers build is expected to depend on the identification of the involved organizers. Organizers who identify with a universalistic group (e.g. the alterglobalist movement), will want to build or strengthen the movement and will therefore want to build a solid, long-lasting mobilizing structure. Those organizers who identify mainly with their own particularistic group (e.g. the Amsterdam Anarchist Group), will join the mobilizing structure to further their own group’s goals and participate on an ad hoc basis. They will not have unconditional support for the structure and therefore prefer to build liquid structures. When organizers who identify with different levels come together in a mobilizing structure, this may lead to problems with regard to what type of structure they will try to build. Identification is also expected to impact on the cooperation within the structure and thereby impact on the sustenance of the structure. The more the other organizers in the structure are seen as ‘us’ the easier cooperation is expected to be. Organizers who identify with universalistic groups are thus expected to be better at cooperating than organizers who identify with particularistic groups. Whether others are seen as part of ‘us’ depends in part on perceived cultural and ideological differences. Such differences not only impact on boundary drawing but also influence negotiation style of the involved organizers, which may increase perceived differences. The greater the perceived differences the more difficult cooperation is expected to be, especially when organizers have to talk about ideological issues. I expect cooperation to be more difficult in solid structures as opposed to liquid structures because there is more need for ideological agreement and they aim to stay together longer. 3|Page RESULTS In this chapter I discussed the building and the cooperation in the most solid mobilizing structure of this study, the Dutch Social Forum (DSF). I expected that building such a solid structure and cooperating in it, would be difficult. Organizers attempting to do so would encounter most problems imaginable. Therefore, the case of the DSF would be an excellent to develop a ‘fullmodel’ for building and maintaining a mobilizing structure. I expected that building the mobilizing structure would start with the personal networks of the initiators, and that this would reflect in the eventual structure. In this case, the initiators had extensive networks. ‘Turn the Tide’ (a large anti-government alliance that initiated the DSF) already included many groups, while the large humanitarian organization (the second initiator of the DSF) had good relationships with many large NGOs. However, it was not possible to include everyone. From the larger and more moderate side, some organizations never joined, and many more never became actively involved in the coalition. Rather, they only showed up to organize a workshop and a stand at the day of the Forum. On the more radical side, some autonomous groups also either did not join or dropped out later, due to the critique they had on the –in their eyes- undemocratic process. The initiators actually never had good relations with these organizers, so the eventual shape of the mobilizing structure reflected the networks of the initiators. Cooperation proved difficult, because of the aim to bring diverse groups together. First of all, many of the groups who joined did not know each other yet and therefore relied on stereotypical ideas about each other. The ‘big ones’ thought the small ones would be too radical and would embarrass them before their members, while the small ones thought the big ones would be too moderate and would try to dominate the mobilizing structure. Groups were thus anxious, and thought the worst of each other. In addition, their differing cultural backgrounds complicated things, as their different negotiation styles reinforced distrust and lead to initial misunderstandings. Stereotypical ideas were strongest between the Horizontals –organized mainly in Dissent- and the Verticals who consisted of the most active group within the DSF. Dissent and other horizontal groups eventually left the DSF. Those in the DSF were not too unhappy to see them leave, from the start they had distrusted them. The Verticals assumed that the Horizontals did not really want to cooperate, but just tried to delay and sabotage the process. They considered the Horizontals to be immature because they did not really try to participate but just criticized. From the side of the Horizontals however, the feeling was mutual. They did not trust the Verticals, felt they were being ignored (which in fact they were), and were sure they would never reach agreement. These ideas did not come from nowhere but where partly based on the experience from previous attempts to build broad mobilizing structures in the past, which had failed. Negative relationships thus lead to negative expectations, which lead to uncooperative behavior and the reinforcement of negative experiences. In this case thus, abeyance structures hindered cooperation rather than facilitated it. In some instances organizers managed to work through their initial problems, thereby overcoming stereotypes and making future cooperation easier. Such a situation however, usually did not last. As the initiators aimed to maintain the structure, it had to be continuously build. Every time a new 4|Page campaign was initiated, new organizers were recruited and the problems started anew. This was a frustrating experience for many of the organizers who did not aim to build a movement but just wanted to organize a Forum. Cooperation was particularly hard when organizers identified with more particularistic groups. Those organizers who identified with the movement wanted to keep everyone in the structure and were motivated to cooperate even when it was difficult. They were motivated to ‘agree to disagree’ as a solution for dealing with ideological issues, and when necessary, were motivated to find practical solutions for pressing problems. For them, forcing a decision was not an option as it would lead to certain groups to leave the structure. This was a constant tension in the mobilizing structure. Such a tension is inherent to all mobilizing structures; organizers want to cooperate and make decisions together, but the more decisions are made, the more difficult it is to keep everyone involved. Some organizers may want to strengthen their structure by unifying and voicing clear demands. Others may want to strengthen the structure by including as many groups as possible, which necessarily means they need to remain vague to give space for diversity. The initiators seemed to have made a clear choice in this trade-off; they wanted to include as many groups as possible. Others however, often wanted to press for stronger language and clear decisions. Those who identified with more particularistic groups, were less concerned about the needs of the others involved in the structure, and were therefore more competitive. This lead to tension in the structure. Competitiveness was seen by the core group, as not wanting to cooperate. Therefore groups who behaved competitively, were ignored, as they were perceived to be trying to frustrate the building of the structure. Organizers earned respect by ‘participating’, whereby participation was conceived of as engaging in the discussions, making concessions and trying to come up with a compromise when they found disagreement. People who ‘only’ voiced their opinion and wouldn’t let themselves to be convinced, lost respect. They were accused of not wanting to cooperate, to obstruct cooperation, and consequently they did not have to be taken seriously. This meant it became very difficult to function in the structure for those who held strong ideological stances, combined with a particularistic identification. As they were unlikely to make concessions, they were excluded from the debate. A practice developed, whereby these ideological groups got the space to voice their opinion, after which everyone just ignored their contribution and continued business as usual. Many of these groups therefore eventually stopped voicing their opinion and became inactive or disengaged. This withdrawal from the structure was then in turn held against them by the others. It was seen as proof that they really did not want to cooperate, and it started a downward spiral. So there was no active exclusion, only self-exclusion. Disengagement by these groups, was often however considered a relief, especially by those who did not aim to build a movement, and therefore did not mind seeing them leave. Those who identified with more particularistic groups were also prone to drop out for another reason. As they did not aim to build a movement, strengthening the own group was their main goal; they participated for instrumental reasons. They did not care too much to include everyone, and mainly wanted the process to be efficient. They saw the DSF as a coordination structure, designed to coordinate efforts to organize an (bi-)annual Forum, rather than a means to build a movement. These instrumentally motivated organizers, preferred to cooperate on a more ad hoc basis, and with more freedom for their own group. They preferred a liquid structure as opposed 5|Page to a solid one. When they felt the structure was not contributing to the good of their group anymore, they left the structure. Their instrumental motivation thus inspired a constant evaluation and reevaluation of the costs and benefits involved in participating in the structure. Although organizers could not change the identifications and motivations of the others, they could however, do something to make cooperation smoother. First of all, organizers stressed that it was very important to never try and push through a decision on an ideological issue. As consensus would never be reached, making a decision would mean to lose part of the participants, and thus weaken the mobilizing structure. In addition, organizers felt that a good preparation of the meeting, particularly making sure that everyone had enough information about the issues and previous meetings, using experienced discussion leaders, and steering the discussion towards a clear proposal, helped meetings to progress more orderly. Linked to the aspect of preparation is the problem of time pressure. Quarrels tend to start when the pressure is high and decisions have to be made. Although this is linked with preparation, in the end, most would agree that a decision eventually needs to be made, as in the end a Forum does need to be set up. Lastly, when problems of distrust and style differences occurred, it helped to split up in smaller groups. In large groups there is not much room for nuances or discussion, everyone makes a declaration of their viewpoints and the points they do, or do not, agree with. Such a practice is likely to enforce stereotypical ideas, especially when people do not know each other yet, see each other as different, and do not trust each other. Breaking up in small groups enables people to get to know each other, overcome stereotypes and discuss a compromise. 6|Page