2. The openess-growth debate between 1995 and now

advertisement

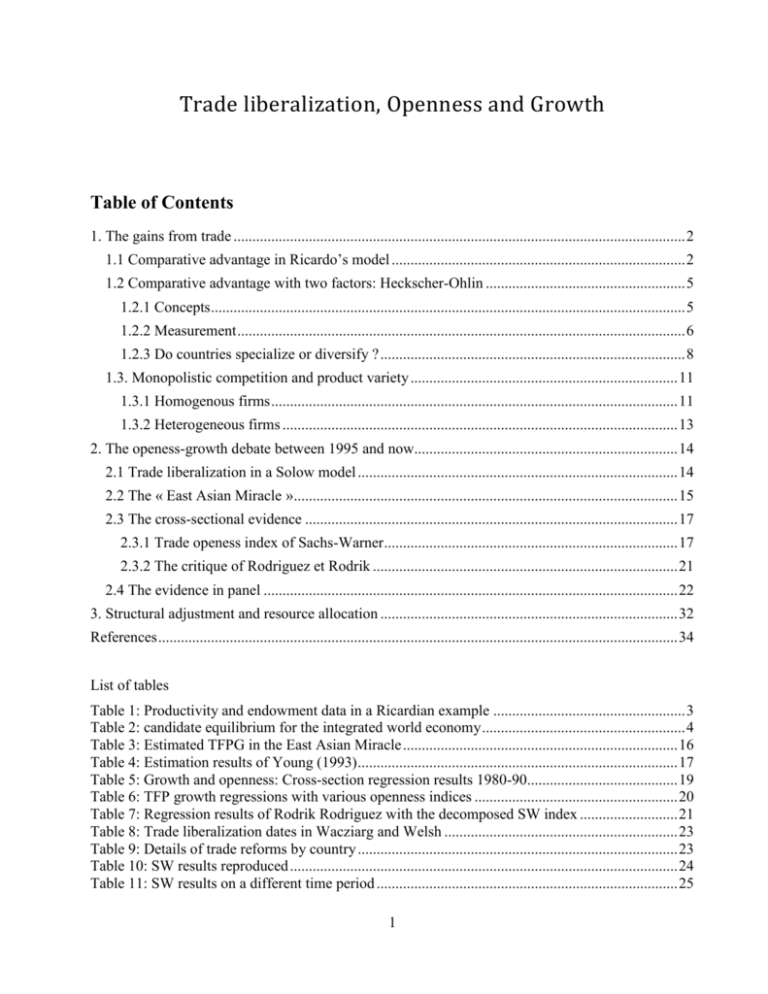

Trade liberalization, Openness and Growth Table of Contents 1. The gains from trade ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Comparative advantage in Ricardo’s model .............................................................................. 2 1.2 Comparative advantage with two factors: Heckscher-Ohlin ..................................................... 5 1.2.1 Concepts .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.2.2 Measurement ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.2.3 Do countries specialize or diversify ? ................................................................................. 8 1.3. Monopolistic competition and product variety ....................................................................... 11 1.3.1 Homogenous firms ............................................................................................................ 11 1.3.2 Heterogeneous firms ......................................................................................................... 13 2. The openess-growth debate between 1995 and now...................................................................... 14 2.1 Trade liberalization in a Solow model ..................................................................................... 14 2.2 The « East Asian Miracle »...................................................................................................... 15 2.3 The cross-sectional evidence ................................................................................................... 17 2.3.1 Trade openess index of Sachs-Warner .............................................................................. 17 2.3.2 The critique of Rodriguez et Rodrik ................................................................................. 21 2.4 The evidence in panel .............................................................................................................. 22 3. Structural adjustment and resource allocation ............................................................................... 32 References .......................................................................................................................................... 34 List of tables Table 1: Productivity and endowment data in a Ricardian example ................................................... 3 Table 2: candidate equilibrium for the integrated world economy ...................................................... 4 Table 3: Estimated TFPG in the East Asian Miracle ......................................................................... 16 Table 4: Estimation results of Young (1993) ..................................................................................... 17 Table 5: Growth and openness: Cross-section regression results 1980-90........................................ 19 Table 6: TFP growth regressions with various openness indices ...................................................... 20 Table 7: Regression results of Rodrik Rodriguez with the decomposed SW index .......................... 21 Table 8: Trade liberalization dates in Wacziarg and Welsh .............................................................. 23 Table 9: Details of trade reforms by country ..................................................................................... 23 Table 10: SW results reproduced ....................................................................................................... 24 Table 11: SW results on a different time period ................................................................................ 25 1 Table 12: Growth and openness in panel ........................................................................................... 26 Table 13: Growth regressed in the liberalization indicator ................................................................ 30 Table 14: Growth regressed on tariff changes ................................................................................... 30 Table 15: Approach 1 with instrumental variable.............................................................................. 31 List of figures Figure 1: Production Possibility Frontier and autarky equilibrium : Portugal..................................... 3 Figure 2: Production Possibility Frontier and autarky equilibrium : Great Britain ............................. 3 Figure 3: The gains from trade............................................................................................................. 4 Figure 4: The gains from specialisation ............................................................................................... 4 Figure 5_ Factor Endowment and PPF: The Rybczynski Theorem .................................................... 5 Figure 6: Factor Endowment and Comparative Advantage: The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem............. 5 Figure 7: Factor endowments and revealed factor intensities .............................................................. 7 Figure 8: Comparative advantage and the survival of exports ............................................................ 7 Figure 9: Fuel exports and GDP volatility ........................................................................................... 8 Figure 10: Export concentration and the level of income .................................................................... 9 Figure 11: Concentration: Individual country trajectories ................................................................... 9 Figure 12: The export re-concentration at high levels of income ........................................................ 9 Figure 13: What are the closing export lines? ................................................................................... 10 Figure 14: Effect of an increase in the custom duty rate on capital equipment in the Solow model. 14 Figure 15: Average growthe for closed and open economies ............................................................ 17 Figure 16: convergence among closed economies............................................................................. 18 Figure 17: Convergence among open economies .............................................................................. 18 Figure 18: Growth and import tariffs ................................................................................................. 22 Figure 19: Growth and NTB coverage ratios ..................................................................................... 22 Figure 20: Time profile of growth around liberalization year ........................................................... 27 Figure 21: Time profile of investment around the liberalization year ............................................... 28 Figure 22: Decomposition of productivity growth : within-sector vs. Structural adjustment ........... 32 Figure 23: Correlation between productivity and variation in employment per sector ..................... 33 1. The gains from trade The tradional theory of international trade suggests that: o Trade among countries generates efficiency gains for all countries, whatever their level of productivity. o Countries specialize according to their comparative advantage, generating efficiencies. 1.1 Comparative advantage in Ricardo’s model In the Ricardian model (not to be confused with the Ricardo-Viner model as we will see later, and which has nothing to do!), The assumptions are • Two countries (Portugal et GB) 2 • • • • • • • Two sectors (wine and drape) Only one factor of production (labor), perfectly mobile between the two sectors Constant returns to scale No transport costs No government intervention Perfect competition (price = cost) At the same price, consumers share their budget equally between wine and drape Thus, in the Ricardian model comparative advantage is determined by the relative productivity of labor, which is the only factor of production. Table 1: Productivity and endowment data in a Ricardian example Productivity Portugal UK Wine 8 1 Drape 4 2 Endowments (labor) 5 20 Figure 1: Production Possibility Frontier and autarky equilibrium : Portugal Wine 40 Indifference Curve Point of Consumption in Autarky PPF (Production Possibility Frontier) Drape 20 Figure 2: Production Possibility Frontier and autarky equilibrium : Great Britain 3 Wine PPF Point of Consumption in Autarky 20 Indifference Curve Drape 40 Equilibrium in the world market after openess of the two economies Table 2: candidate equilibrium for the integrated world economy Production Portugal UK Total Wine 40 0 40 Drape 0 40 40 Consumption Wine 20 20 40 Drape 20 20 40 Figure 3: The gains from trade Wine Indifference Curves PPF World Price Line export import Drape Figure 4: The gains from specialisation 4 Wine Point of Production Indifference Curves Lines of World prices PPF Drape 1.2 Comparative advantage with two factors: Heckscher-Ohlin 1.2.1 Concepts Figure 5_ Factor Endowment and PPF: The Rybczynski Theorem Steel The impact of foreign investments PPF initial The impact of immigration Textile Figure 6: Factor Endowment and Comparative Advantage: The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem 5 Point of production after structural adjustment Indifference curves Steel “trade triangle” Relative Price on world market (tissu moins cher) Point of consumption after structural adjustment PPF Autarky relative price Textile 1.2.2 Measurement When there are more goods than factors of production, in general the direction of trade (who exports what) is not determined.1 However, overall countries tend to export goods corresponding more or less to their factor endowments Traditionally, we calculate the Balassa index of revealed comparative advantage : denote xin the exports of product n by country i, xi the total exports of country i, xn world exports of product n, and x world exports. The Balassa index then is: in xin / xi xn / x The problem with this index is that it assumes that if country i exports product n, it has a comparative advantage in this product; but the index does not use the factor endowment of country i. Using data on factor endowments from UNCTAD, we can determine the « revealed » factor intensity of each product by taking the average endowments of the countries that are exporting it. If i is the endowment of capital of country i, the capital intensity of the good n is: n i in i where in is a modified version of the Balassa index since i in 1 . 2 The advantage of this normalization is that it allows us to put together national factor endowments and the products’ revealed intensities in the same formula. If the theory is true, the exports of countries should be relatively less scattered around their endowments. 1 Can be found in trade flows with a continuum of goods as in Dornbusch Fisher Samuelson. Caution: If some countries subsidize the exports of products that do not correspond to their comparative advantage, the computation is distorted (e.g. agricultural products to Europe). We must therefore correct for this bias in the computations. 2 6 Figure 7: Factor endowments and revealed factor intensities Pakistan 2003-5 4 10 8 6 4 6 8 10 Revealed Human Capital Intensity Index 12 12 Costa Rica 1993 2 0 0 2 Endowment point 0 50000 100000 150000 Revealed Physical Capital Intensity Index 0 200000 50000 100000 150000 Revealed Physical Capital Intensity Index 200000 Figure 7 (ctd) Tunisie : new export products 0 50000 100000 150000 Revealed Physical Capital Intensity Index 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Revealed Human Capital Intensity Index 12 12 Tunisie 2003-5 200000 0 50000 100000 150000 Revealed Physical Capital Intensity Index 200000 Moreover, the more the exported goods are far away from the factoral endowment of the countries, the less they survive on the world markets, despite the effect is quantitatively small : Figure 8: Comparative advantage and the survival of exports 7 2 3 4 5 6 7 Length of trade relationship and distance to CA 2 2.2 2.4 2.6 (mean) std_dist_1 (mean) length 2.8 3 Fitted values 1.2.3 Do countries specialize or diversify ? On the other hand, the theory suggests that countries should specialize in their comparative advantage rather that to diversify. But specialization in raw materials, for example, can be synonymous of "imported volatility": .8 .6 .4 .2 GAB 0 Coefficient of variation of GDP, 2000-2007 1 Figure 9: Fuel exports and GDP volatility 0 20 40 60 Fuel share in exports 80 100 Recent studies also suggest that the decline in the volatility of GDP observed in recent decades in the United States is largely linked to the diversification of the economy (in services). On the other hand, generally the concentration of exports follows a non-monotone path as countries develop : first diversification, then reconcentration. We measure the concentration of exports in similar way as we measure the concentration in income, by three indices: (i) Gini, (ii) Herfindahl, and (iii) Theil. Here we considered the index of Theil, whose formula is : 8 1 xi xi ln i n x x T (1) 8 Figure 10: Export concentration and the level of income Uganda 2000 Predicted 6 More concentrated than predicted 4 Uganda 2010 2 Less concentrated than predicted 0 20000 40000 60000 GDP per cap, 2005 PPP dollars Theil index Fitted values 80000 Theil index, Uganda And the reconcentration ocurred in the individual trajectories of countries : 4 5 Figure 11: Concentration: Individual country trajectories IRL 3 GRC 2 ESP 15000 GBR 20000 25000 30000 35000 GDP per capita, PPP (constant 2005 international $) 40000 Which countries are those that re-concentrate? Figure 12: The export re-concentration at high levels of income 9 7 5000 6 4000 5 Theil index 3000 2000 4 Theil index 3 0 1000 number of exported products # active export lines 0 20000 40000 GDP per capita PPP (constant 2005 international $) 60000 Active lines - quadratic Active lines - non parametric Theil index - non parametric Theil index - quadratic How can we explain the reconcentration? Essentially the inertia of trade flows, export lines that are closed have factor intensities corresponding to weaker endowments than those of countries that close. For example, the average of trade lines closed by the EU corresponds to the combined endowment of human and physical capital of Indonesia. These lines should be long gone, but they remain open by inertia. Figure 13: What are the closing export lines? 2 4 6 8 10 12 Human capital 0 50000 100000 Product intensities 150000 200000 Country endowments Capital In short, the theory seems to stick quite well with empirical observation, although the "content factors" does appear to explain only a small part of international trade. We therefore need other models to have a more complete view of its determinants. On the other hand, so far everything discussed was essentially static: allocative efficiency considerations tell us nothing about the growth. In the models of endogenous growth, growth is mainly due to innovation ; international trade plays only an indirect role (i.e. through innovation). 10 So we will discuss the relationship between trade and growth from an essentially empirical point of view, except a small detour to the Solow model in Section 3 1.3. Monopolistic competition and product variety 1.3.1 Homogenous firms The monopolistic competition model The Heckscher-Ohlin model explains trade by differences in factor endowments. It cannot explain the trade between countries with similar endowments, and even less intra-industrial trade. We will now focus on an alternative model proposed by Krugman (1980), called « monopolistic competition». The ingredients for a model of monopolistic competition are : o Product differentiation that generates a finite elasticity for each firm o Economies of scale The gains of trade in the MC model come from competition, which compresses margins and prices. Consider the following example from Krugman, Obstfeld and Mélitz (2012), pp 168-177 Let S be the volume of national trade, which we take as exogenously given (independant of the prices of the firms active in this market) which is of course unrealistic but simplifies the analysis greatly. Let n be the number of firms active in the market, b a parameter of demand (linear), Qi the quantity sold per company i, pi its price and p the average price in the market. Total cost is the sum of a fixed cost F and a marginal cost c : Ci F cQi which gives average cost of : ACi F c Qi (2) Demand function facing firm i : 1 Qi S b pi p n (3) In a «symmetric equilibrium» where all firms set the same price pi p , it can be seen from (12) that Qi S / n ; market shares are equal. Optimal pricing by profit-maximizing firms equalizes marginal cost and marginal revenue. To derive marginal revenue, invert (3) to get the demand price: pi 1 Qi p bn bS Revenue is price multiplied by quantity 11 (4) piQi Qi Qi 2 pQi bn bS (5) and marginal revenue is the derivative of revenue w.r.t. quantity: 1 2Qi p bn bS 1 Qi Q p i bn bS bS RM i (6) pi pi Qi bS Marginal cost is simply c. Optimal pricing is therefore pi Qi c bS (7) Qi bS (8) Or pi c "mark-up" In the symmetric equilibrium where all firms adopt the same price, Q = S/n , optimal pricing simplifies to pi p c 1 bn i (9) In this equilibrium, average cost is found by substituting Q = S/n in (4), which yields AC c Fn S (10) With free entry, profits must be zero, which means that price has to equal average cost: c 1 Fn c bn S (11) S bF (12) or n2 which determines the number of firms compatible with zero profits in the market (no incentive for additional entry). In this model, gains from trade arise because of o Economic integration that creates a bigger market o Increasing competition, reducing margins This can be seen by « merging » two countries with equal size S as part of a big-bang tradeliberalization experiment. 12 Effects of trade liberalization We do the comparison that is commonly done in international trade between an equilibrium in autarky and an equilibrium with free trade where all barriers are eliminated. The effect is illustrated in a numerical example in the excel file Exemple concurrence monopolistique.xlsx. Suppose that the two countries are of equal size and that there is no transportation cost. Then their combined size is S ' 2S , so the total number of firms is n' S' 2S S 2 1.414n bF bF bF and the equilibrium price and quantity are p' c Q' 1 p bn ' S ' 2S S 2 2Q Q n' n 2n So : o The total number of varieties available to any consumer in the two-country area increases (there are fewer in each country but consumers have access to both) o The equilibrium price is lower, and so are profit margins (not shown but easy to calculate) o Output per firm increases. Damn it, everything is fine in this world? 1.3.2 Heterogeneous firms Note that the trade liberalization induces firm exit, since n ' 2n 2n . In a symmetric equilibrium, which firms will exit is indeterminate. But suppose now that potential entrants differ in their marginal cost ci, in accordance with new “heterogeneous-firm” models. Those with marginal cost higher than the « choke price » don’t enter. Intercept of demand facing each firm: Using (13), Qi = 0 implies p choke 1 p bn And the slope of the demand curve is : dpi 1 dQi bS Trade liberalization means that pchoke goes down as n goes up, while the slope becomes “less negative” as S goes up. Thus, under the effect of an increase in S and the induced increase of n, the demand curve rotates anticlockwise. o The demand increases for big firms with low marginal cost o But it decreases for firms with higher marginal cost, which leads to the exit of some firms. 13 2. The openess-growth debate between 1995 and now 2.1 Trade liberalization in a Solow model Everything that we saw at the beginning of this chapter was static. Is there any reason to think that trade liberalisation could accelerate the growth? Yes if trade liberalization affects the price of capital goods, for example. To see this, we take the Solow model and assume that the domestic price of capital goods (the capital) is : pK pK* 1 tK where pk* is the world price of one unit of capital (one « machine ») and tk is the customs duty on imported capital. Assume, to simplify, that pk* 1 , that is if we measure the capital in dollars, then one unit is worth a dollar . Rewrite the law of motion of capital as : K I I K K pK 1 tK Then we have : I K dk 1 tK k kLˆ dt L 1 I K ˆ kL L 1 tK L 1 1 tK sk n k . A high customs duty therefore lowers the curve in Figure 14; the steady state (the intersection of the curves, that are respectively representing the first term on the right of the equation above, and the second term) moves to the left (at a level of capital per worker lower) and the rate of growth during the transition to steady state, slows. Figure 14: Effect of an increase in the custom duty rate on capital equipment in the Solow model 14 In the particular case of capital goods, the link between trade liberalization is therefore direct (and obvious). This explains the 'climbing' structures of tariffs, prevailing in most developing countries : low or zero tariff on capital goods, moderate tariff rates on intermediate products used as inputs in the industry, and the highest rates on consumer goods. 2.2 The « East Asian Miracle » Empirically, what can we say about the relationship between trade and growth? The « East Asian miracle » is the title of a World Bank report published in 1994 and dedicated to the spectacular growth of the Asian tigers (compared to other continents, in particular Africa and Latin America). This report had considerable visibility although it was highly controversial. The approach was a “growth accounting” one based on a Cobb-Douglass production function : Yit Kit Lit H it yit ln Yit (0.13) Log-linearizing gives an estimable growth equation yit kit it hit uit where ui is the error term. Let ei be the residual of the estimation in (14), i.e. 15 (14) eit yit ˆ kit ˆ it ˆhit (0.15) We will give a name to this residual : TFP (Total Factor Productivity). Taking first differences (i.e. growth rates, since everything is in logs) we define Total Factor Productivity Growth (TFPG) as eit eit eit 1 TFPGit (0.16) This gives us a decomposition of sources of growth in two components : o Accumulation, i.e. what is predicted by (14), o TFPG or improved Efficiency (the residual) This decomposition is very important. If accumulation (especially capital) is the dominant contribution to growth, the recipe for economic policy is the "mobilization of savings" for investment. This can be done - and has been historically - abruptly by taxing agriculture to generate the resources needed for investment. Extreme cases: the Soviet Union under Stalin. It is also what inspired many economic policies in Africa. On the other hand, if the TFPG is dominant, then is something else. The problem is that as the TFPG is a residual, by definition it is not known what it is, and we could put what we want as interpretation. Table 3: Estimated TFPG in the East Asian Miracle Average TFP 1970-90 (% per year) Taiwan Hong-Kong Korea Japan Thailand Singapore Malaysia 3.76 3.64 3.10 3.48 2.49 1.19 1.07 Latin Am. Afr. sub-sah. 0.13 -0.99 There is clearly a difference in the nature of growth between the SE Asia and the remainder (AL and ASS). The TFPG is dominant in Asia, not elsewhere. Explanation: trade openness that forces local businesses to restructure and improve the efficiency. Unfortunately, the same year when the preliminary draft of the « East Asian Miracle » circulated, Alwyn Young published a paper that showed the labour factor was improperly measured (underestimated) for SEA (South East Asia) countries in the report of the Bank, the residual measured correctly was a bit smaller for these countries. Even more of a miracle! 16 Table 4: Estimation results of Young (1993) Source : Young, 1993 2.3 The cross-sectional evidence 2.3.1 Trade openess index of Sachs-Warner Idea: correlate the growth in the period 1980-90 with a measure of trade openess. Bianary measure : either open or closed country. « Closed » if one of more of the following criteria are satisifed: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Average tariff greater than 40% Rate of coverage of non-tariff barriers (quotas etc.) greater than 40% of imports Black market currency premium greater than 20% during the decade Export State Monopoly Socialist Economy SW found a strong correlation between growth and their measurement of the opening. Already in descriptive statistics, the difference is clear : Figure 15: Average growthe for closed and open economies 17 Source : Sachs Warner (1995) In addition there is convergence among the open countries but not closed countries: Figure 16: convergence among closed economies Source : Sachs Warner (1995) Figure 17: Convergence among open economies 18 Source : Sachs Warner (1995) The cross-section regression results confirm the descriptive statistics (table 5). Table 5: Growth and openness: Cross-section regression results 1980-90 Source : Sachs Warner (1995) Edwards (1998) attempted to show that the results of Sachs and Warner were robust and not the effect of a particular approach. It includes all of the openess measures (Sachs and Warner and other) and systematically explores the correlation between these measures and the TFPG. 19 OPEN Sachs-Warner WDR Openess Index of the World Bank (composite) LEAMER Residual of an equation of openess BLACK Balck market premium on currrencies TARIFF Average import tariff QR Rate of coverage of quantitative trade barriers HERITAGE Trade-distortion perception index CTR Revenue on import taxes in proportion of the value of imports WOLFF Another residual of a regression of openess SW results are robust; several other similar exercises give the same results Table 6: TFP growth regressions with various openness indices Source : Edwards 1998. 20 Basically, the message is that regardless of the measure of openess that we take, the correlation with the TFPG seems well-established. The message of the East Asian Miracle was fundamentally correct even if the measures are differentgood this is. 2.3.2 The critique of Rodriguez et Rodrik Rodriguez et Rodrick (2001) show the opposite. They do an exercise of brutal deconstruction of all this econometrics, in particular of the econometrics of Sachs Warner. 1 si tariffs < 40% & NTB < 40% et pas SOC SQT sinon 0 1 si BMP < 20% & pas de MON BM sinon 0 Table 7: Regression results of Rodrik Rodriguez with the decomposed SW index 21 Figure 18: Growth and import tariffs Source : Rodriguez et Rodrik (2001) Figure 19: Growth and NTB coverage ratios Source : Rodriguez et Rodrik (2001) So what explains the differences of TFPG, is not so much trade policy stricto sensu, but rather macroeconomic policy (the overvaluation of the exchange rate measured by the premium on currencies) and export monopolies. But what country had exchange rates overvalued in the 1980s? But that had exchange rates overvalued in the 1980s? Latin America. Which country had export monopolies? Africa. 2.4 The evidence in panel 22 All first generation studies were cross-sectional. Wacziarg and Welsh (2008) remake the estimates in panel data by carefully identifying the date of trade liberalization (while SW did not date, since they were using a cross-sectional over a decade). Employing a panel allows to use the fixed-effects estimator (dummy variables that capture country-invariant characteristics over time). The effect is much better identified, as it is "within-country" that is to say, it filters the heterogeneity between countries due to unrelated trade openness factors. Table 8: Trade liberalization dates in Wacziarg and Welsh Table 9: Details of trade reforms by country 23 Results : Reproducing exactly the exercise of SW, they find the same findings : Table 10: SW results reproduced 24 Contrariwise, when running the same regressions on another time period (the 90s) , nothing stays significant : Table 11: SW results on a different time period 25 What to make of it? The answer comes with panel regressions where the fundamental explanatory variable is the date of trade liberalization; the date of the liberalization contains additional information that is not distorted by other unexplained differences between countries entre pays (since we use the difference in time for each country). Table 12: Growth and openness in panel 26 Once doing this, the results become correct for all periods – far more convincing. Figure 20 displays the results in a more intuitive way. Time is normalized to be zero in the year of trade liberalization for each country (so if Colombia liberalises in 1995, 1994 = -1, 1995 = 0, 1996 = 1 for Columbia ; if Chile liberalises in 1970, 1969 = -1 etc.). Each point on the curve is the average of the sample growth at t = -10, t = -9, etc. We observe an accelaration of growth of about 1.5 percentage points around the year zero. Figure 20: Time profile of growth around liberalization year 27 Figure 21 shows the same finding for investment. We observe a spectacular rise in the rate of investment after the liberalization. Figure 21: Time profile of investment around the liberalization year On the other hand, the identification problem remains still unsolved in Wacziarg and Welsh due to the fact that the trade reforms were often implemented at the same time as reform packages that affected several other sectors of the economy (macroeconomic stabilizations, privatizations, governance reforms, etc.) and oftentimes also coincide with changes in government. So : is it really the trade liberalization causing the effects or other simultaneous developments? Estevadeordal et Taylor (2009) revisited the question in the different ways where the second one is interesting in itself to understand for the used methodology. Approach 1 (« simple differences ») The regress the change in growth on the change in tariffs in a panel of countries—a standard technique. With i representing a country, t the time, git the growth of country i at time t, 28 xit hit , zit a country-specific vector (human capital and characteristics of governance), and it the average of tariffs of country i in time t. git git gi ,t 1 (17) And the same for other variables put in differences. The equation becomes git 0 1gi ,t 1 xit α2 3 ln 1 it uit (18) Approach 2 (« differences in differences ») E&T use as natural experiment the liberalization implemented by a number of countries during trade negotioations in Uruguay (the « Uruguay Round » that took place between 1986 and 1994). Certain countries liberalized their tariffs; they form the « treatment group » ; other countries that didn’t liberalize are put in the « control group ». Again, the sample structure is a panel, but now the estimation technique is called « differences in differences ». This term expresses that we compare the performance before and after a certain date where the treatment starts (the first difference), but for two groups, the treatment and the control group (second difference). This estimation technique is commonly used in medical sciences. With Di being a dummy variable marking belonging to the treatment group and Tt the treatment period (after the Uruguay round) ; so 1 if t 1994 Tt 0 if t < 1994 The basic equation becomes git 0 1Di 2Tt 3 Di Tt xi 0α4 uit (19) Treatment _ effect And the coefficient 3 gives the treatment effect. We can also re-write (19) in a simpler way with fixed effects for countries and years: git Di Tt i t uit (20) Treatment effect Finally a third way of writing and estimating this equation consists of defining two long periods ( t0 1975 1989 and t1 1990 2004 ), which gives us a two-period panel, and taking the change between those two periods : gi gi ,t1 gi ,t0 (21) gi 0 1 gi ,t0 x i α 2 3 Di ui (22) Which yields The basic results of the Diff-in-Diff approach (DD) are displayed in Error! Reference source not ound.. The first column uses the average of tariffs for all goods as regressor of interest (« liberalizer indicator »); the second column uses the average of tariffs only on consumption goods, the third 29 uses the average on tariffs on equipment goods and the fourth uses the average tariff on intermediate goods. We find that the coefficients are significant and estimated more precisely for the equipment goods than for consumption goods. However, the effects are rather weak. Table 13: Growth regressed in the liberalization indicator The results of the first approach are very similar, but with the opposite sign since lower tariffs accelerate growth : Table 14: Growth regressed on tariff changes 30 Again, the coefficients are very small (signalizing a very weak effect) and only significant at the 10% level (signalizing that the effect is not well measured). Contrariwise, the coefficient on the tariffs for equipment good sis two times higher than the coefficient for consumption goods, which is in line with the basic growth model of section 2.1. Endogeneity The two approaches face similar problems, firstly endogeneity and secondly selection. They only handle the first problem, where the problem is that the variation in tariffs and the variation in growth could be explained by the same omitted variable, for example a change in government.3 The instrumental variable is the interaction between two things: 1. The intensitiy of the Great Depression in the observed countries 2. The level of tariffs in the countries before the Uruguay round. The idea of the first element is that suffered more in the Depression have more than others lost the faith in liberalism and adopted more protectionist policies afterwards, which could have survived until today and resulted in less willingness for a liberalization. The idea of the second element is that for liberalzing, countries must have entered the Uruguay round with high tariffs (otherwise no need for liberalization) So low intensity of the Great Depression × high level of tariffs predict a strong liberalization in the Uruguay round. Table 15: Approach 1 with instrumental variable 3 In the seond approach, we face a selection problem. The approach relies on the hypothesis that the decision to take the treatment is uncorrelated with the potential effect of the treatment. In fact, if the countries that liberalized were systematically more likely to benefit from the treatment, we cannot use the equation (7) to deduct that the same effect would have worked in the countries that were not treated. Therefore we have to control for this selection effect that is always present when the treatment is not given at random, but this control is not done here. 31 We note that the effect is now stronger and more significant (it’s the « second stage » that we care about; we have -0.05 now vs. -0.03 before, and the effect is significant at 5%). 3. Structural adjustment and resource allocation Is this the end of the debate ? Not yet. In a recent paper, McMillan et Rodrik (2010) have decomposed the growth of productivity and shown a result opposing the message of the beginning of the course : o The productivity growth in a sector is comparable across countries ; particularly there is no substantial difference between Africa and America as before o In contrast, in favour of a structural adjustment : in these two regions ressources have moved from sectors with high productivity growth towards sectors with low productivity growth. Supposing that the productivity of the manufacturing sector was a weighted average of the productivity of several sectors. qt j j q j with j j 1 . We can express its variation, qt qt qt 1 as q q j j j Croissance "within" j q j j j j q j Structural adjustment small--we ignore it! Representing the first term in grey and the second in black in averages per region, McMillan and Rodrik (2011) obtain in Figure 22: Figure 22: Decomposition of productivity growth : within-sector vs. Structural adjustment 32 Source : McMillan and Rodrik (2011). The grey component doesn’t really vary from one region to the other. However, the black part really makes a difference. The structural adjustment has moved resources to the wrong place! The case of Argentina is particularly interesting (Figure 23). Figure 23: Correlation between productivity and variation in employment per sector Source : McMillan and Rodrik (2011). 33 References Edwards, Sebastian (1998); “Openness, Productivity and Growth: What Do We Really Know?”; Economic Journal 108, 383-98. Estevadeordal, Antoni, and Alan Taylor (2009), “Is the Washington Consensus Dead? Growth, Openness, and the Great Liberalization, 1970s-2000s”; IDB working paper IDB-WP-I38; Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. McMillan, Margaret S. and Dani Rodrik, “Globalization, Structural Change and Productivity Growth,” Working Paper No. 17143, NBER (http://www.nber.org/papers/w17143), June 2011. Rodrik, Dani, and F. Rodriguez (2001), “Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptic's Guide to the Cross-National Evidence”; in Ben S. Bernanke and Kenneth Rogoff, editors, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, Volume 15, p. 261 – 338; Boston, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Sachs, Jeffrey, and Andrew Warner (1995), “Economic Reform and the Process of Global Integration”; Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 26, 1-118. Wacziarg, Romain, and K. Welch (2008), “Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence”; World Bank Economic Review 22, 187-231. The World Bank (1993), The East Asian miracle : economic growth and public policy; Washington, DC: The World Bank. 34