1AC – Plan The United States should legalize nearly all marihuana

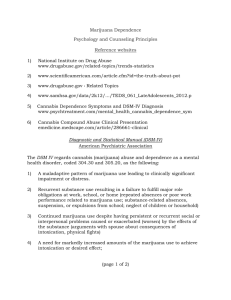

advertisement