Social Capital Formation in Urban Elementary Schools: Teachers

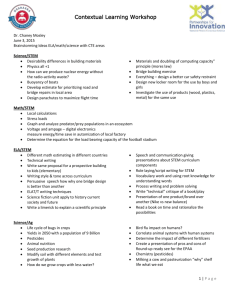

advertisement