DOCX file of Building Professions and Technicians

advertisement

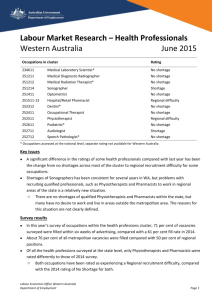

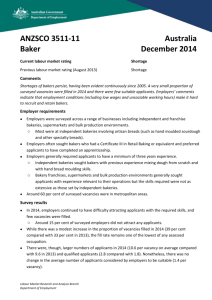

Labour Market Research Building Professions and Technicians Australia Occupations in cluster Rating 2014-15 Number of years in shortage 5 years to 2014-15 * Building professions 1331-11 Construction Project Manager No Shortage 1 2321-11 Architect No Shortage 0 2322-12 Surveyor Shortage 4 2326-11 Urban and Regional Planner No Shortage 0 2332-13 Quantity Surveyor Shortage 3 Building technicians 3121-11 Architectural Draftsperson No Shortage 0 3121-12 Building Associate No Shortage 0 3121-14 Construction Estimator Recruitment Difficulty for positions in residential construction requiring five to 10 years experience. 2 * Ratings based on research undertaken in the June quarter 2015. Key issues The labour market for building professions and technicians has been soft in recent years and there have been few shortages. o There was very little change in employers’ recruitment experiences in the year to 2014-15, and shortages remain limited, with large fields of applicants vying for most vacancies. Figure 1: Proportion of vacancies filled (%), average number of applicants and suitable applicants per vacancy (no.), Building professions and technicians, Australia, 2007-08 to 2014-15 Applicants per vacancy - RHS ISSN: 2201-2931 100 90 80 70 60 (%) 50 40 30 20 10 0 Suitable applicants per vacancy - RHS Proportion of vacancies filled - LHS 75 70% 57% 70% 73% 74% 74% 60 63% 45 (no.) 32.4 39% 24.9 21.4 13.9 11.9 30 23.3 12.3 15 4.9 0.9 1.9 1.9 1.7 3.0 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 4.1 3.3 2.4 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 0 Source: Department of Employment, Survey of Employers who have Recently Advertised. Occupational coverage varies slightly over the time series. Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 1 Vacancies for graduate and junior positions were generally readily filled, and Graduate Careers Australia (GCA) data1 suggest that some graduates are finding it difficult to gain initial employment. Reflecting the soft demand for workers, a small number of vacancies were withdrawn and some employers showed a lack of urgency in their recruitment, being willing to wait for the ideal candidate. Some employers noted that they receive unsolicited applications or that they had little need to recruit That said, across the assessed occupations, 4 per cent of employers did not attract any applicants and a further 16 per cent did not attract any suitable applicants. o This was most evident for vacancies for surveyors, quantity surveyors and construction estimators. Unfilled vacancies were more likely to be for senior positions and some senior roles were filled through head-hunting, networking or engaging a recruitment agent. Survey results Surveyed vacancies were across a broad range of sectors and specialisations, but the majority were for residential work. The results for 2014-15 are very similar to those for 2013-14. o Around 74 per cent of vacancies were filled (unchanged from last year) and there were 23.3 applicants, of whom 2.4 were considered by employers to be suitable (compared with 24.9 and 3.3, respectively, in 2013-14). It is, however, markedly easier to recruit than it was prior to the global financial crisis. o Since 2007-08, the proportion of vacancies filled has increased by 35 percentage points and the numbers of applicants and suitable applicants have also risen (up by 18.4 and 1.5, respectively). Results by occupation Building technician vacancies were more readily filled than those for building professions. o About 81 per cent of building technician vacancies were filled and there were 26.4 applicants per vacancy on average, of whom 2.9 were suitable. o By comparison, 70 per cent of building professional vacancies were filled and there were averages of 21.6 applicants and 2.2 suitable applicants, per vacancy. There are marked differences in employers’ recruitment experiences across the assessed building profession and technician occupations, although there were relatively large applicant numbers for every occupation (Table 1). o Employers recruiting for building associates filled the highest proportion of vacancies (92 per cent) and attracted notably large fields of applicants and suitable applicants (31.4 and 4.9 respectively, on average, per vacancy). o Applicant fields were also large for construction manager positions, with an average of 40.5 applicants per vacancy. 1 GCA, Graduate Destinations, 2014 Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 2 o Those recruiting for surveyors and quantity surveyors had the most difficulty, filling the lowest proportion of vacancies (45 per cent and 56 per cent, respectively) and attracting few small number of suitable applicants (1.4 and 1.3 per vacancy on average). Table 1: Proportion of vacancies filled (%), average number of applicants and suitable applicants per vacancy (no.), Building professions and technicians, Australia, 2014-15 Occupation Building professions Construction Project Manager Architect Surveyor Urban and Regional Planner Quantity Surveyor Building technicians Architectural Draftsperson Building Associate Construction Estimator Proportion of vacancies filled (%) 70 83 80 45 85 56 81 78 92 70 Applicants per vacancy (no.) 21.6 40.5 19.2 15.2 18.9 13.6 26.4 22.8 31.4 27.4 Suitable applicants per vacancy (no.) 2.2 3.1 2.4 1.4 2.3 1.3 2.9 2.0 4.9 1.8 Source: Department of Employment, Survey of Employers who have Recently Advertised Results by location Vacancies were difficult to identify in some states and territories and employers suggest that demand for these workers varies significantly across jurisdictions. Possibly reflecting this, recruitment experiences also varied markedly across the states (Figure 2). o Recruitment was easiest in South Australia, with the highest proportion of vacancies filled (92 per cent) and the largest number of applicants and suitable applicants (28.6 and 3.8, on average, per vacancy). o Although very few vacancies were identified during the research period in Tasmania, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory, employers in the two territories experienced the greatest difficulty recruiting. They filled a low proportion of vacancies and attracted the smallest fields of suitable applicants. The majority of surveyed vacancies were in metropolitan areas, but the research results suggest that recruitment is more difficult in regional locations. o Employers in regional areas filled 66 per cent of their vacancies compared with 76 per cent filled by their metropolitan counterparts. o Candidate fields were also smaller in regional areas (an average of 18.0 applicants per vacancy, of whom 1.9 were considered by employers to be suitable, compared with 24.4 applicants and 2.5 suitable applicants in metropolitan areas). Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 3 Figure 2: Proportion of vacancies filled (%), average number of applicants and suitable applicants per vacancy (no.), Building professions and technicians, by state, 2014-15 Applicants per vacancy - RHS Suitable applicants per vacancy - RHS 100 80% 75% 74% 60 40 74% 40 65% 70 (%) 50 50 92% 90 80 Proportion of vacancies filled - LHS 28.6 26.8 27.6 30 23.3 22.9 (no.) 19.2 20 30 20 10 10 1.8 3.1 1.7 3.5 3.8 2.4 0 0 NSW VIC QLD SA WA Australia Source: Department of Employment, Survey of Employers who have Recently Advertised. Figures for other states and territories have been omitted due to the low number of surveyed vacancies Reasons applicants were unsuitable The most common reasons applicants were considered by employers to be unsuitable related to experience. Many applicants o lacked experience in a particular sector or specialisation (experience was not seen as readily transferable) o did not meet employers’ expectations in terms of length of experience o did not have local experience (often defined as the state or city in which the vacancy was located) o were unable to demonstrate experience in managing projects or leading staff (required for senior roles). A number of employers regarded applicants who had obtained their qualification overseas as being unsuitable, in part, due to their lack of familiarity with Australian standards and regulations. Other reasons employers considered applicants to be unsuitable included o being unqualified o unfamiliarity with particular software, such as Revit, AutoCAD or GIS systems o not being registered or holding relevant endorsements or licences o poor soft skills, including communication and interpersonal skills. Demand trends Employment Employment of building professionals and technicians averaged around 193,200 over the year to May 2015.2 Employment growth has been strong, up by 4.3 per cent over the year to May 2015 and by 28.2 per cent over the past ten years (compared with growth of 1.8 per cent and 19.1 per cent, respectively, for all occupations). 2 ABS, Labour Force, May 2015, four quarter average Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 4 Vacancies Advertised vacancy numbers remain relatively low by historical standards, but have risen over the past year (Figure 3).3 o There were 19.0 per cent more vacancies advertised in the year to June 2015 than there were over the same period in the previous year, but the number of vacancies remains around half the peak level recorded in the year to October 2008. Figure 3: Vacancy levels, Building professionals and technicians, Australia, December 2006 to June 2015 (indexed) 250 200 150 100 50 0 Source: Department of Employment, Internet Vacancy Index, 12 month moving average (Dec 2006 = 100). Data are for ANZSCO unit groups and include occupations not assessed by the Department. Industry activity Construction activity is the main driver of demand for building professionals and technicians. There has been a considerable difference in activity levels between the construction sectors in recent years (Figure 4). o Engineering construction drove activity from early 2011 until late 2013. Since then, there has been a downturn in engineering construction with most mining-related construction being completed. The value of engineering construction work done fell by 18.6 per cent over the year to March 2015.4 o Low interest rates have contributed to a recovery in residential building construction and there was an 11.4 per cent increase in residential building activity over the year to March 2015. Non-residential building, however, fell by 0.4 per cent over the period.5 o The Performance of Construction Index confirms the reduced activity in the engineering and commercial sectors and stronger activity across the residential housing and apartment building sectors.6 3 Department of Employment, Internet Vacancy Index, June 2015 ABS, Engineering Construction Activity, March 2015, chain volume measures, trend 5 ABS, Building Activity, March 2015, chain volume measures, trend 6 Australian Industry Group, Performance of Construction Index, July 2015 4 Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 5 Figure 4: Value of construction activity work done ($ billions), Building and engineering construction, March 2005 to March 2015 40 35 Building construction Engineering construction ($ billions) 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Source: ABS, Building Activity and ABS, Engineering Construction Activity, chain volume measures, trend Training Workforce educational profile New supply to the building professions and technicians workforce is difficult to estimate due to the multiple entry pathways to these occupations. This diversity is highlighted in their educational attainment profiles (Table 2) and employers’ requirements. o The proportion of surveyed employers who required applicants with qualifications ranged from 15 per cent for those recruiting for construction estimators to almost 100 per cent of those recruiting for building professionals. Table 2: Highest educational attainment, Building professions and technicians, 2011 (% share) Occupation Construction Project Manager Architect Surveyor Urban and Regional Planner Quantity Surveyor Architectural Draftsperson Building Associate Construction Estimator Diploma or Bachelor Postgraduate Advanced degree qualification Diploma (% share of workers with qualification) 27.4 16.0 31.2 8.1 0.5 5.9 68.0 21.0 7.8 23.5 43.9 4.1 2.7 6.0 48.5 33.8 6.3 13.5 58.7 3.4 12.5 38.2 20.5 5.1 56.6 10.0 5.6 1.0 31.2 16.9 16.9 3.0 Certificate III or IV Source: ABS, Census of Population and Housing Graduate outcomes Higher education Over the past five years, employment outcomes have weakened for graduates in all of the key fields leading to employment in these building professions (Table 3). Outcomes for bachelor degree graduates in Urban Design and Regional Planning and masters by coursework degree graduates in Architecture are now below average.7 7 GCA, Graduate Destinations, 2014, customised tables, Australian resident graduates. Outcomes are proportion of those available for full-time work who were employed full-time four months after completion of their qualification. A masters degree is required for new registration as an architect. Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 6 o The averages for bachelor and masters by coursework graduates across all fields of education were 68.1 per cent and 80.5 per cent, respectively. There is, though, a good match in terms of training and occupational employment for these fields of education, with the vast majority of those graduates who are working full-time being employed in the occupation for which they trained. Table 3: Graduate outcomes, Proportion in full-time employment for selected fields Field of education (qualification level) 2014 (%) Building Construction Management (Bachelor) Architecture (Masters) Geometric Engineering/Surveying (Bachelor) Urban Design and Regional Planning (Bachelor) 88.5 71.3 83.9 65.0 5 year change (percentage points) -6.6 -13.3 -8.1 -23.7 Source: GCA, Graduate Destinations, Australian resident graduates Vocational education and training Employment outcomes for students who complete a vocational education and training qualification for architectural, building and surveying technician are strong, with 88.3 per cent of graduates employed after graduation (67.2 per cent employed full-time), compared with 77.6 per cent across all occupations.8 Almost three quarters of those who are employed work in the intended occupation or in other occupations for which the training is relevant. Outlook The Department projects employment to increase over the five years to November 2019 for all of the unit groups in this cluster (Table 4), but expects growth for urban and regional planners and architectural, building and surveying technicians to be weaker than the all occupations average (10.0 per cent). Table 4: Projected employment growth, Building professionals and technicians, 5 years to Nov 2019 Occupational unit group Construction Managers Architects and Landscape Architects Cartographers and Surveyors Urban and Regional Planners Architectural, Building and Surveying Technicians Change - 5 years to Nov 2019 (no.) (%) 13,800 17.1 5300 18.0 1600 13.0 400 4.3 5100 9.1 Source: Department of Employment. Data are for ANZSCO unit groups and include occupations not assessed as part of the Skill Shortage Research There is a pipeline of residential building work to support a recovery in the construction sector. o The number of building approvals increased by 14.4 per cent over the year to June 2015.9 o The Treasury forecasts private dwelling investment to increase by 6.5 per cent in 2015-16 and by 4.5 per cent in 2016-17.10 8 NCVER, Student Outcomes, 2014, data combine two survey periods. Outcomes are the proportion in employment (full-time and part-time) six months after completion of their training 9 ABS, Building Approvals, June 2015, trend 10 The Treasury, Budget Strategy and Outlook, 2015-16 Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 7 o The Australian Industry Group and Australian Constructors Association forecast that growth in commercial construction will be subdued over the next two years, but anticipate solid growth in multi-level apartment development.11 o Master Builders Australia (MBA) reports that, despite earlier optimism about a recovery in commercial construction, conditions in this sector have fallen but for the residential sector, the index for current conditions indicates that conditions are good.12 Demand for labour from the engineering construction sector is expected to be moderate as the pipeline of engineering work is diminishing. o The value of engineering construction work yet to be done by the private sector fell by 26.4 per cent over the year.13 o The Australian Industry Group and Australian Constructors Association indicate that the current downturn in engineering construction is expected to continue.14 o The Department of Industry and Science reports a decline in the number of resource sector related projects (particularly, those at the feasibility and publically announced stages).15 o That said, the Government’s Infrastructure Growth Package (which includes the $5 billion Asset Recycling Initiative) will likely boost demand for building professionals and technicians.16 11 Australian Industry Group, Construction Outlook, May 2015 MBA, National Survey of Building and Construction, June 2015 13 ABS, Engineering Construction Activity, March 2015, original 14 Australian Industry Group, Construction Outlook, May 2015 15 Department of Industry and Science, Resources and Energy Major Projects, April 2015 16 The Treasury, Budget Paper No 3: Federal Financial Relations, 2015-16 12 Labour Market Research and Analysis Branch Department of Employment Page 8