Thesis word docBW - ARAN - Access to Research at NUI Galway

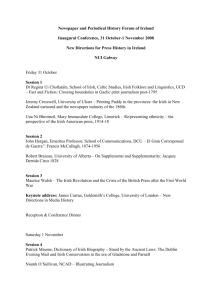

advertisement