appliedethics1 squire foundation.prefad

advertisement

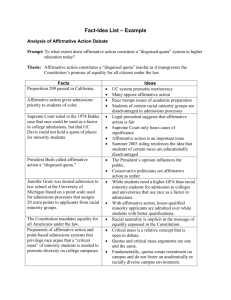

Applied Ethics Module Applied Ethics: Introduction This module addresses questions in three topics drawn from applied ethics: the moral status of animals, affirmative action in universities (i.e., preferential admissions), and bioethics (commercial surrogacy, conceiving one life to save another). The format for this module is consistent from question to question. Two days are suggested for each question, although it is possible to discuss relevant cases in one day or to extend analysis for a longer unit. Each question begins with cases intended two to spark and anchor discussion. Cases are followed by important considerations and guiding questions, as well as directions for analysis of the relevant arguments. Although readings are suggested for each question, it is possible to guide good discussion with the cases alone. Footnotes also direct teachers to additional sources for their own background reading. Applied Ethics: Preferential Admissions Day 1 The Issue Among society’s goods are opportunities for admission to competitive colleges and universities. Given the scarcity of seats and abundance of applicants, how should opportunities for higher education be distributed fairly? Are preferential admissions for groups who historically have been targets of discrimination a just or fair practice? Or is it unjust to consider factors such as race in university admissions? Affirmative action in education, or preferential admissions, is a policy that favors qualified minorities over qualified nonminority candidates with the goals of remedying discrimination, achieving diversity, and attaining equal opportunity. Assign Hopwood v. State of Texas (1996) as reading for Day 1, or use the capsule summary of the case and court ruling below.1 The Case of Cheryl Hopwood2 Review with students the following summary of the Hopwood case, including her personal and academic background, the University of Texas (UT) Law School admissions policy, the basis for its decision not to admit Hopwood, and Hopwood’s case against the UT School of Law: Cheryl Hopwood did not come from an affluent family. Raised by a single mother, she worked her way through high school, community college, and California State University at Sacramento. She then moved to Texas and applied to the University of Texas Law School, the best law school in the state and one of the leading law schools in the country. Although Hopwood had compiled a grade point average of 3.8 and did reasonably well on the law “Hopwood v. State of Texas” can be found in Justice: A Reader, ed. Michael Sandel (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 240-243. 2 Teachers also might introduce the Bakke case. In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly upheld an affirmative action admissions policy of the medical school at University of California at Davis. The Bakke case is discussed in suggested Ronald Dworkin reading for Day 2. 1 1 Applied Ethics Module school admissions test (scoring in the 83rd percentile), she was not admitted. Hopwood, who is white, thought her rejection was unfair. Some of the applicants admitted instead of her were African American and Mexican American students who had lower college grades and test scores than she did. The school had an affirmative action policy that gave preference to minority applicants. In fact, all of the minority students with grades and test scores comparable to Hopwood’s had been admitted. Hopwood took her case to federal court, arguing that she was a victim of discrimination. The university replied that part of the law school’s mission was to increase the racial and ethnic diversity of the Texas legal profession, including not only law firms, but also the legislature and the courts…In Texas, African Americans and Mexican Americans comprise forty percent of the population, but a far small proportion of the legal profession. When Hopwood applied, the University of Texas law school used an affirmative action admissions policy that aimed at enrolling about fifteen percent of the class from among minority applicants. In order to achieve this goal, the university set lower admission standards for minority applicants than for nonminority applicants. University officials argued, however, that all of the minority students who were admitted were qualified to do the work, and almost all succeeded in graduating from law school and passing the bar exam. But that was small comfort to Hopwood, who believed that she’d been treated unfairly, and should have been admitted.3 Guided Discussion of Arguments For and Against Hopwood Ignoring the legal dimension, does Hopwood have a legitimate case from a moral point of view? Were her rights violated by UT admissions policy? After dividing students into groups, introduce the following questions and ask each group to discuss the merit of Hopwood’s case from a moral point of view. After discussing the case, each group should share its evaluation of competing arguments on the broad issue of preferential admissions and present its conclusion on whether Hopwood’s rights were violated in her particular case. Consider: 1. What factors are taken into account in college admission? How is race like or unlike these other factors? [Discuss which factors are outside the student’s control.] 2. What factors should be taken into account in college admissions? If race shouldn’t be taken into account, what other factors also should be excluded? Which factors should be the sole basis for university or college admissions? 3. Is an admissions policy based partly or entirely on traits that are outside the control of the applicant inherently unfair? 4. Who should determine the goals, social good, or mission of a university? Should a university be free to define their admissions policies to serve any social purpose they deem desirable? Does it matter whether the university is a public or private institution? 5. Can the concept of rights apply with justification to collectives as well as individuals? 6. Has UT violated Hopwood’s rights? If so, what rights are at stake? At the end of the discussion, take a poll. How many students agree that UT treated Hopwood unjustly? 3 Michael J. Sandel, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009), pp.167-68. 2 Applied Ethics Module Court Ruling and Consequences Share with student the finding of the court in the Hopwood case and its consequences for UT School of Law admissions. In Hopwood v. Texas (1996), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit argued that an educational institution can only justifiably implement an affirmative action program if it is designed simply to correct for the past discrimination of that very institution. The goal of educational diversity was judged not sufficient to justify an affirmative action policy. Prevailing on equal protection grounds, Hopwood made the first successful legal challenge to a university’s affirmative action policy in student admissions since Bakke (1978).4 After seven years as a precedent in the 5th Circuit, the Hopwood decision was abrogated in a U.S. Supreme Court decision which judged that race can be used as a factor in admissions as long as quotas are not used. Assign reading for Day 2: Ronald Dworkin, “Bakke’s Case: Are Quotas Unfair?” in Justice: A Reader, ed. Michael Sandel (New York: Oxford, 2007), pp. 248-255 Day 2 Spend the second day probing the central backward and forward-looking arguments surrounding preferential admissions. Note that both supporters and critics share the assumption that admissions are justified in terms of the principle of equal opportunity. Supporters of preferential admissions argue that the principle must be enforced to eliminate discriminatory practices. Critics argue that a group standard is inconsistent with the basic ideal of individual merit underlying the principle of equal opportunity. Invite a critical response from students to the arguments sketched below: Which set of arguments is stronger? What objections might be raised against each argument? How would the advocate of preferential admissions reply to each objection? Backward-Looking Argument: Rectifying Historical Injustice5 Backward-looking arguments justify affirmative action as compensation for past unjust injuries. Represent the two chief arguments: 1. Affirmative action compensates blacks for injuries they suffer as a result of unjust racial prejudice and discrimination directed at them. This argument has two versions: (a) compensation for specific acts of discrimination (e.g., denial of admissions to a university solely because of one’s race) or (b) compensation even if they have never have personally suffered specific acts of racial discrimination because, as Justice Thurgood Marshall said, racism is so pervasive that no blacks have managed to escape its impact. At UT School of Law, the percentage of the entering class that was African American dropped from 5.8% in 1996 to 0.9% in 2007. See James P. Sterba, Affirmative Action for the Future (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), pp. 21-22. 5 This overview of the chief backward-looking and forward-looking arguments draws extensively from two sources. See Bernard Boxill and Jan Boxill, “Affirmative Action” in A Companion to Applied Ethics, ed. R. G. Frey and Christopher Heath Wellman (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp.118-141; Walter Feinberg, “Affirmative Action” in The Oxford Handbook of Practical Ethics, ed. Hugh LaFollette (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 272-297. 4 3 Applied Ethics Module 2. Affirmative action is justified as compensation to present-day blacks for injuries they have sustained as a result of the enslavement and unjust racial treatment of their African and African-American ancestors. Consider: Explore with students two ways that the legacy of slavery has arguably harmed the present black population and benefited the white population: (a) the black population starts off with less wealth and education than other people because their ancestors were slaves who had less wealth that might be passed down to their descendants; (b) historical exploitation of the black population conferred undeserved benefits upon the white population that have been passed down to their descendants. Objections: Then explore with students possible objections to backward-looking arguments: (a) Legislation aimed at eliminating present discrimination against individuals is sufficient to address the effects of historical racial prejudice. It is better to end current discrimination than to introduce a group-sensitive policy that would justify special treatment for historically oppressed groups.(b) Why do preferential admissions give special consideration to some historically discriminated groups but not to others (e.g., Italians, Irish). (c) If a debt is owed, its costs are an unfair burden on neither the non-discriminating offspring of immigrants who were neither victimizers nor beneficiaries of slavery. (c) Why should affluent members of historically oppressed groups benefit from preferential admissions when the same opportunities are closed to economically disadvantaged but equally talented white males? Any group-sensitive preferential admissions policy should be guided by socioeconomic differences rather than race or sex. Reply: Students then may wish to offer replies to the above objections: Comparing the plight of slaves to immigrant groups ignores the distinction between forced and voluntary immigration. The slave trade also was much worse than discrimination directed at other immigrant groups. Finally, the color of white immigrants’ skin enabled them to integrate within generations. The argument for needs-based preferential admissions ignores the role of deep cultural stigmas in both cultural and economic deprivation. Forward-Looking Arguments Forward-looking arguments argue the future benefits from affirmative action, chiefly improved educational environments and the reduction of racial stratification and prejudice. According to this argument, the consequences of affirmative action help make opportunities more equal. According to the equal opportunity principle, places and positions should be awarded to those who are best qualified for them. All individuals must be evaluated for these positions strictly on the basis of their qualifications and forbids discrimination based on irrelevant considerations. Invite students to discuss the question of what makes one candidate more highly “qualified” than another. Then introduce the following arguments. Argument for Equal Opportunity If talented people are not properly educated, society is not making the best use of the talents available to it. Those who defend affirmative action say that formal equality of opportunity is not enough. Being allowed to enter a race and toe the starting line is not necessarily an equal opportunity to compete or to win if one has never received opportunities for adequate training. For example, if historical stereotypes discourage women from studying engineering, affirmative action is necessary 4 Applied Ethics Module to afford women greater opportunities to become qualified and to compete for positions in the profession. Objection: Justice Harlan famously claimed that the American Constitution is color-blind. On his view, the equal opportunity principle is violated if (a) we assume that citizens have the right to be evaluated for desirable positions solely on the basis of their qualifications and (b) if color and sex are irrelevant factors used to justify unequal treatment. If we give special consideration to race, gender, or ethnicity, we only perpetuate the discriminatory practices of distributing opportunities unequally and unfairly. The consequences of affirmative action may be desirable for blacks and women, but the practice is still unacceptable because it violates the rights of whites to be evaluated solely on the basis of their qualifications. If we accept this argument, affirmative action is reasonably characterized as “reverse discrimination.” Reply: The above objection rests upon the questionable assumption that scores and grades alone indicate qualifications for positions. Each state establishes law schools to train their graduates for service in its communities. If the state believes that black lawyers are far more likely than white lawyers to practice in black communities, and if the law school gives equal weight to the interests of black and white people in receiving legal service, consideration of race would be relevant as a qualification for admission. On this view, affirmative action can help society give more equal consideration to the like interests of all without being guilty of arbitrarily favoring one group at the expense of another. Argument for Enhanced Educational Environment: Promoting Diversity Another important forward-looking argument is that preferential admissions produce a better educational environment for everyone, including white students. On this view, the optimal education is not one in which all students share the highest possible grades and scores. Differences in experience, background assumptions, and social attitudes are critically important for an educational atmosphere of pluralism, dialogue, and open inquiry. Objection: The purpose of a university is not social engineering for the sake of a social goal, however laudable. Its mission should be to promote and reward academic excellence based upon the merit of individual student achievement and promise. (See “A Final Pass” below for reply.) Argument for Reduced Racial Stratification and Prejudice Preferential admissions will reduce racial stratification through greater opportunities for minorities in universities and the professions. As a consequence, racial prejudice will be reduced as well. Objection: Historical precedents challenge the conclusion that reduced racial stratification results in reduced racial prejudice. For example, assimilated Jews living in Europe after legal emancipation gained access to high positions yet suffered from growing anti-Semitism due, at least partly, to their success and resentment among non-Jews. Even if preferential admissions have the effect of undermining stereotypes, this is no reason to assume that racial prejudice will decrease. Blacks may be resented precisely because they hold positions successfully. Reply: It may be true that the reduction of racial stratification is not enough to justify preferential admissions. But what must be considered is not only the racist attitudes of whites but the effect of preferential admissions on blacks’ response to racial prejudice: “With the elimination of racial stratification, it will no longer be rational for blacks to infer that they can succeed…Affirmative 5 Applied Ethics Module action is justified because it provides for compensation in the form of restored hope…What really robbed blacks of hope was not only racism, but the apparent effects of racism in keeping them down.”6 Black conservative Shelby Steele expresses a dissenting view that preferential admissions are a salve to the guilt of white liberals who patronize blacks and thereby reinforce their condition of dependency. A Final Pass: The Question of Merit and Purpose of a University7 After discussing the above arguments, return to the case of Cheryl Hopwood. Take a second poll to see whether students have changed their minds or have found new reasons for their position. Were Hopwood’s rights violated? Specifically what rights? Possible answers include: (a) the right not to be judged according to factors outside her control; (b) the right to be judged according to academic merit alone. Evaluate the argument of Ronald Dworkin, summarized in Michael Sandel’s Justice, that preferential admissions is justified once we recognize that (a) most criteria used in university decisions involve factors outside applicants’ control (e.g., home state, athletic prowess, musical talent, aptitude for standardized tests) and (b) that no student has a right to be judged by merit. The argument rests on Dworkin’s central distinction: Moral Desert: a reward or honor that acknowledges individual virtue, merit, or excellence. Legitimate Expectation of Benefit: a consistent allocation of society’s benefits based on publicly stated social goals Dworkin argues that university admissions should depends solely on whether the applicant meets the admission standards set according to the specific social goals of the university’s mission (i.e., legitimate expectation of benefit). As Sandel writes, “…Admission is justified insofar as it contributes to the social purpose the university serves, not because it rewards the student for her merit or virtue, independently defined.”8 Consider: Students should critically assess Dworkin’s claim that legitimate expectation to benefits should replace moral desert in deciding the justice of preferential admissions. If we accept Dworkin’s distinction, should colleges and universities be free to define their missions as they wish? Note that at one time UT Law School was segregated, denying admission to Heman Marion Sweatt on the grounds that the school did not admit blacks. His case led to a landmark Supreme Court decision, Sweatt v. Painter (1950), which challenged segregation in higher education. Is there a principled distinction between the discrimination practiced by universities in the days of the segregated South or “restricted” admissions of Jews and the use of race in contemporary preferential admissions programs? Boxill and Boxill, “Affirmative Action,” p. 126. Also see Feinberg, “Affirmative Action” for his appeal to the “strategy of simultaneity,” pp. 293-94. A culture can be created and maintained that perpetuates discriminatory practices even when no one wishes to discriminate. For example, if a high school coach knows that no opportunities for black quarterbacks are available at the college level, he will train black athletes for other positions. Preferential admissions is a strategy of simultaneity that breaks such cycles: “It is intended both to affect the way in which members of targeted minorities think about their opportunities for a good life within established institutional structures, and to change the way in which established institutional structures respond to minorities” (294). 7 See Michael Sandel, “Arguing Affirmative Action” in Justice, pp. 167-183 6 8 Sandel, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? p. 174. 6 Applied Ethics Module 7