The Critical Theory of Angela Davis

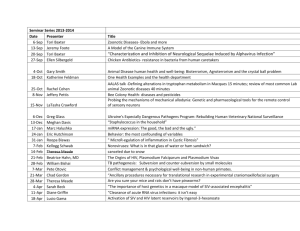

advertisement

Freedom and Resistance: The Critical Theory of Angela Davis Iliana Cuellar California State University, Los Angeles icuella2@calstatela.edu This paper is a draft. Please do not cite without permission from author. It is rare to see women philosophers taught regularly in non-feminist philosophy classes. It is not due to lack of work since there are considerable amounts of women philosophers in every tradition and branch. I attribute it to a willful ignorance in which the only valid reason for the exclusion would be if professors are not familiar with their work, in which case, I have a follow up question; why not? By all means wade through Plato, Hume, Descartes, and even our professor’s work, but why is it not equally as important to wade through Arendt, Beauvoir, Butler, Lloyd, Kristeva? Although the number of women in philosophy is rising, the amount of women of color is still considerably small. Neoliberal concepts of multiculturalism and diversity might address the problem through selective hires for the sake of “not looking bad” and to make their programs “look good.” We risk tokenization in our fields and question whether our work is actually valued in academe. It makes sense for many women of color intellectuals to then be involved locally in their communities and grassroots organizing. On the opposite spectrum, our academic affiliation can be looked down on in our activist circles. Some accuse us of spending too much time in our books, classrooms, reading papers at conferences and not enough time organizing and engaging in direct action. Many know of Angela Davis’ activism, but we forget that she is philosopher. After leaving the Institute for Social Research to participate in Black liberation struggles in the U.S., she continued to study under Herbert Marcuse at the University of San Diego. She is seldom mentioned in discussions and university classes, and almost always excluded from anthologies and readers, on Critical Theory and the ISR. Very few people read her work as a part of the Critical Theory tradition as well, but it is important to recognize her contribution to this school of thought. What distinguishes her critical theory from many of the other Frankfurt school theorists is a philosophy informed around issues that affect her as an African American woman and the larger Black community in the U.S. We can point at the Eurocentric, androcentric nature of philosophy for her exclusion, but I believe the incongruence mostly lies in the need for urgent and immediate action that is indigestible to institutional philosophy and the university as very tools used for social control. Emancipation, Civil Rights Movement, Black liberation movement, and contemporary movements like #BlackLivesMatter recognize that not only is it necessary to further the movement on the page, but physical resistance is absolutely necessary. In this way, Davis most resembles the aims of early critical theory—social criticism and social transformation—informed through Karl Marx’ “Theses on Feuerbach” and his powerful statement, “The philosophers up to now have interpreted the world, in various ways. The point is to change it.” The latter aim of critical theory—social transformation—seemed to at one point become less significant or at least limited only to the page. While Marcuse writes to Davis, “So you felt that the philosophical idea, unless it was a lie must be translated into reality: that it contained a moral imperative to leave the classroom, the campus, and to go and help the others, your own people to whom you still belong-- in spite of (or perhaps because of) your success within the white Establishment.”1 Adorno tells Angela, on her decision to move back to the States to participate in the Black liberation struggle, that the “desire to work directly in the 1 Herbert Marcuse. “Letter to Angela” radical movements of that period was akin to a media studies scholar deciding to become a radio technician.”2 Critical theorist respective aims as doing social philosophy striving for social change were lost in translation. I believe that in many women of color’s writing there lies a strong politic of accessibility; a commitment to stray from educational alienation by making sure that people can access their work. Audre Lorde sums up one aspect of a politic of accessibility beautifully in “Age, Race, and Class” in which she states, “Of all the art forms, poetry is the most economical…the one which can be done between shifts, in the hospital pantry, on the subway, and on scraps of surplus paper.”3 Accessibility politics takes into account the lack of resources in the communities of the audiences we are trying to address. Their writing addresses their communities, which usually systemically lack access to quality education and feed into either the prison-industrial-complex via the school-to-prison-pipeline or exploitative cheap labor. Critical theorists have argued that what is most accessible are products of the culture industry reinforcing positivity. Art, books, philosophy are supposed to counter one-dimensionality, positive thinking and be negative forces thus anything readily accessible is suspect. Accessibility, however, does not necessarily entail conformity. Making negative thinking and writing more accessible to poor communities, communities of color, immigrant communities, or who we can term “active agents” (in lieu of the Marxist concept of a “subject of history” since there exists plurality of subjects) is revolutionary. The relationship between accessibility and negativity, positivity is nuanced. Easier to read and follow does not mean that there isn’t an impenetrability and a struggle to not only grasp but also implement theoretical work. 2 3 Davis, Y. Angela. “Marcuse’s Legacies” Lorde, Audre. “Age, Race, Class, and Sex,” Her choice to demonstrate her critical theory centered on a philosophical concept of freedom through the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, a former slave, rather than hypotheticals and counterfactuals is demonstrative of her divorce from what Marcuse terms “one-dimensional philosophy.” Of this decision she states, “The history of Black literature provides, in my opinion, a much more illuminating account of the nature of freedom, its extent and limits than all the philosophical discourses on this theme in the history of Western society” and later she states, “Philosophy is suppose to perform the task of generalizing aspects of experience, and not just for the sake of formulating generalizations, of discovering formulas, as some of my colleagues in the discipline believe.”4 The use of hypotheticals is infuriating when you are dealing with concepts that are seen realized through people’s actual lives. While an upper middle class white intellectual can sit around and ponder the concept of freedom whether a priori or material, the contradictory nature of being Black and a non-Black person of color in the United States asks for more immediate action that cannot be fully realized in the classroom as they simultaneously try battling discrimination experienced through slurs, physical violence, and lower wages. Davis’ freedom is conceived through a theoretical system rooted in consciousness, and addresses arguments concerning freedom throughout the history of philosophy that are simplified dichotomies of subjective/objective, free-will/deterministic, interior/exterior and conceives of an interconnected mind consciousness and physical resistance constructing a continual process of liberation. Many philosophers have argued that freedom lies a priori within the definition of man summed up in a statement such as 4 Davis, Angela. Lectures on Liberation. San Francisco: City Lights Books. 2010. “man is free.” She addresses, Sartre’s essential notion of freedom in particular as a contemptible notion of freedom. Davis’ raises the question, as a response to statements such as “man is free,” whether Black men were not human or if there lie incongruence with the essence of humanity and its appearance such that a non-free man could exist. The goal, however, is not to figure out whether any of these are true or false but to challenge the very dichotomies and call them into question. She states, “Most important here will be the crucial transformation of the concept of freedom as a static, given principle into the concept of liberation, the dynamic, active struggle for freedom.” The first step in striving for freedom is the rejection of the present situation and realization of an alternative. Self-consciousness, as Davis details, is a realization of ability to not be subordinate or enslaved and the master’s greater dependence on the slave for affirmation of selfhood or superiority. In her “Lectures on Liberation,” Davis points to Frederick Douglass’ realization that he can be free in his exclaiming, “Let me be free...Why am I a slave...It cannot be that I will live and die a slave.” This exclamation marks a starting point in liberation or a continual struggle for freedom. It does not mean that the moment marks Douglass’ freedom and he is now free but it’s more an inaugural statement to an ontological commitment to liberation. The realization of ability to be free has a material counterpart—a physical retaliation and what Davis’ calls resistance. She states, “…the violent retaliation signifies much more than the physical act: it is refusal not only to submit to the flogging, but refusal to accept the definitions of the slave master.” Of this theoretical framework she states, “The road towards freedom, the path of liberation is marked by resistance at every crossroad: mental resistance, physical resistance, resistance directed to the concerted attempt to obstruct that path.” In the beginning of her lectures she poses the question of whether freedom is fully subjective or objective, we can see that it is hard to imagine one without the other and that freedom requires a mind consciousness with the physical manifestation rejecting white-supremacist ideology. Eugene V. Debs calls for unity with his statement, “While there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” A collective process for freedom is also struggle against a freedom constructed by culture industry as a tool of repression, which can create tensions and divisions among people. Davis’ critical theory engages in praxis and also contains critiques of social movements as a philosophy of activism. Davis’ details this in both Women, Race, and Class, and her autobiography; she mentions issues of racism in women’s suffrage movement and sexism in Black liberation struggles demonstrating the ways in which society can use freedom in order to suppress different oppressed groups of people. Freedom is also commodified. The illusion of freedom created by culture industry uses rhetoric of choice and limits our capacity to think of liberation of all peoples. The idea of freedom centers on free market values and the ability to choose from many options offered where the amount of options you have really depends on capital. The feminist stance of pro-choice is an example of a neoliberal construction of freedom: people have the choice to pick from many different options of birth control and access to abortions of which the government should have no say. Many scholars have argued that this is a simplistic argument and does not account for the systemic racism and classism in “pro-choice” rhetoric because many poor people and people of color could not access these resources without government funded family planning programs. We can see how culture industry constructs freedom and in the U.S. this merges through intersections of gender, race, sexuality, and class. We can then define the Marxist concept “subject of history” as more complex especially in the United States. A radical movement cannot be defined through the proletariat but as several mass movements across the globe towards a new social order. Globalization and mass communication has made this necessary and possible. When the same security company, G4S, is responsible for the borders along Gaza and the West Bank as well as the militarization of the U.S./Mexico border, it becomes clear that Palestinian liberation struggle is connected to justice for immigrants migrating from the Global South usually fleeing countries still recovering from stale economies sucked dry by U.S. imperialism. The “subject of history” needs to shift to encompass the other forms of social control such as white supremacy and cisheteropatriarchy because even within the oppressed there is further stratification. These divisions within a similarly oppressed group perpetuate constructed ideas of freedom as stated before with the example of women and Black suffrage. In the U.S., a documented immigrant is grateful to not be undocumented and the undocumented immigrant is grateful to have fled the poverty or political unrest they faced in their home country. Still, there lies a feeble division between these two people constructed by larger society defined as legality versus illegality in which legality is deemed free and illegality is criminalized and, although feeble, is a powerful weapon of division. We need to start connecting to different movements locally and globally in acts of solidarity and resistance. Through her writing, speeches, demonstrations, and pedagogy, Angela Davis’ calls for a social transformation beyond preexisting philosophical dichotomies of what is and what is not resistant, what is and what is not free, but argues for synthesis and dynamic liberation towards freedom. She strays from a given definition of freedom or the essence of man to challenge the appearance in which unfree men exist. Unfreeness crosses over into racialized, gendered, and sexualized lines. As Frederick Douglass realized that his individual freedom did not abolish slavery and as he connected Black suffrage with women’s suffrage, Davis urges us to realize that our own struggles for justice, rights, and liberation are tied to that of global struggles, local struggles across age, race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, ability, and other intersections.