Catford`s approach to translation

advertisement

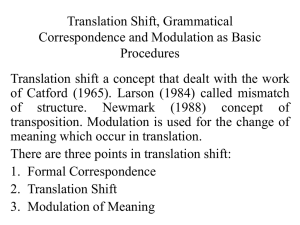

Catford’s approach to translation equivalence Applying a more linguistic-based approach to translation, Catford’s approach to translation equivalence (1965) took another direction from that of Nida and Taber. Influenced by the linguistic work of Firth and Halliday, he refined Halliday’s grammatical ‘rank-scale’ approach to develop the hypothesis that equivalence in translation depends upon the availability of formal correspondence between linguistic items at different structural levels and ranks, particularly at the sentence level. Catford’s main contribution in the field of translation theory is the introduction of the concepts of types and shifts of translation The main translation shifts that may take place in total translation are of two main kinds: 1. Category Shifts. 2. Level Shifts. Category Shifts are usually divided into: a- Structure-shift: e.g. The boy went to school (SPC) ( ذهب الولد إلى المدرسةPSC). blue car (MH) ( سيارة زرقاءHM) The structure of the English sentence is (S.P.C.), whereas the structure of the Arabic equivalent sentence is (P.S.C.). As for the nominal group “blue cars”, its structure in English is (MH), that is the modifier preceded the head; whereas in the case of its Arabic equivalent, the order is the opposite. b. Class-Shift: i.e. the equivalent TL item is a member of a different class compared with that of the SL item: e.g.: green cars (M. i.e. modifier). ( سيارات خضراءQ i.e. qualifier). In spite of the fact the both items “green” in English and " "خضراءin Arabic are members of the grammatical class “adjective” , yet the English one operates as modifier in the nominal group structure,; whereas the Arabic one operates as qualifier in the nominal group structure. This is why it is considered to be a case of (class-Shift). c. Unit-Shift: By unit-shift is meant shifts at the grammatical ranks; i.e. the translation equivalent of an SL item at a certain grammatical rank happens to be an TL item at a different rank. e.g. ذهب الشاب إلى البيتThe young man went home. The English lexical item 'home' which is at the word rank has its translation equivalent at a different grammatical rank, that of the group. This is a case of unit-shift. d. Intra-system translation-shifts: i.e. shifts in such grammatical systems as number, article, etc. e.g.: John and Ali went out. خرج جون وعلي They will be back before midnight. سيعودان قبل منتصف الليل The equivalent of Arabic dual in English is the plural. When it is the case that a singular in one language is given a plural equivalent in another language or vice versa, for instance, one may call such shifts intra-system shifts. The same in applicable to other systems such as the article. For instance. English (SL) A man is an animal. Arabic (TL) اإلنسان حيوان The equivalent of the English indefinite article “A” in this instance happens to be the definite article in Arabic, whereas the equivalent of the second indefinite article “an” in the same sentence happens to be zero. One of the problems with Catford’s formal correspondence, despite its being a useful tool for comparative linguistics, is that it is not really relevant in terms of assessing translation equivalence between ST and TT. This pushed theorists to turn to Catford’s other dimension of correspondence, namely textual equivalence, which he defines as “any TL text or portion of text which is observed to be the equivalent of a given SL text or portion of text" (ibid: 27). Catford goes on to state that textual equivalence is achieved when the source and target items are “interchangeable in a given situation…” (ibid: 49). This happens, according to Catford, when “an SL and a TL text or item are relatable to (at least some of) the same features of substance” (ibid: 50). For this purpose, Catford used a process of commutation, whereby a competent bilingual informant or translator is consulted on the translation of various sentences whose ST items are changed in order to observe “what changes if any occur in the TL text as a consequence” (ibid: 28). Criticism of Catford's approach Catford has faced scathing criticism for his linguistic theory of translation. For example, Snell-Hornby (1988) argues that Catford’s definition of textual equivalence is ‘circular’, and his reliance on bilingual informants is ‘hopelessly inadequate’. In addition, his example sentences are ‘isolated and even absurdly simplistic’ (ibid 1920). She considers the concept of equivalence to be an illusion. Snell-Hornby does not believe that linguistics is the only discipline which enables people to carry out a translation, since translating involves different cultures and different situations which do not always correlate. Bassnett (1980) also criticized Catford’s theory of translation describing it as restricted since it implies a narrow theory of meaning (ibid: 16-17). Fawcett (1997) believes that Catford’s definition of equivalence, despite having a façade of scientific respectability, hides a notorious vagueness and a suspect methodology, adding that much of his text on restricted translation seems to be motivated by a desire for theoretical completeness, which is out of touch with what most translators have to do (ibid: 56).