The Mississippians

advertisement

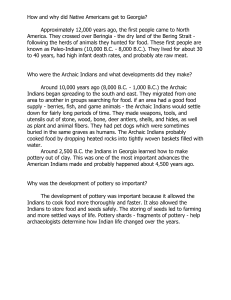

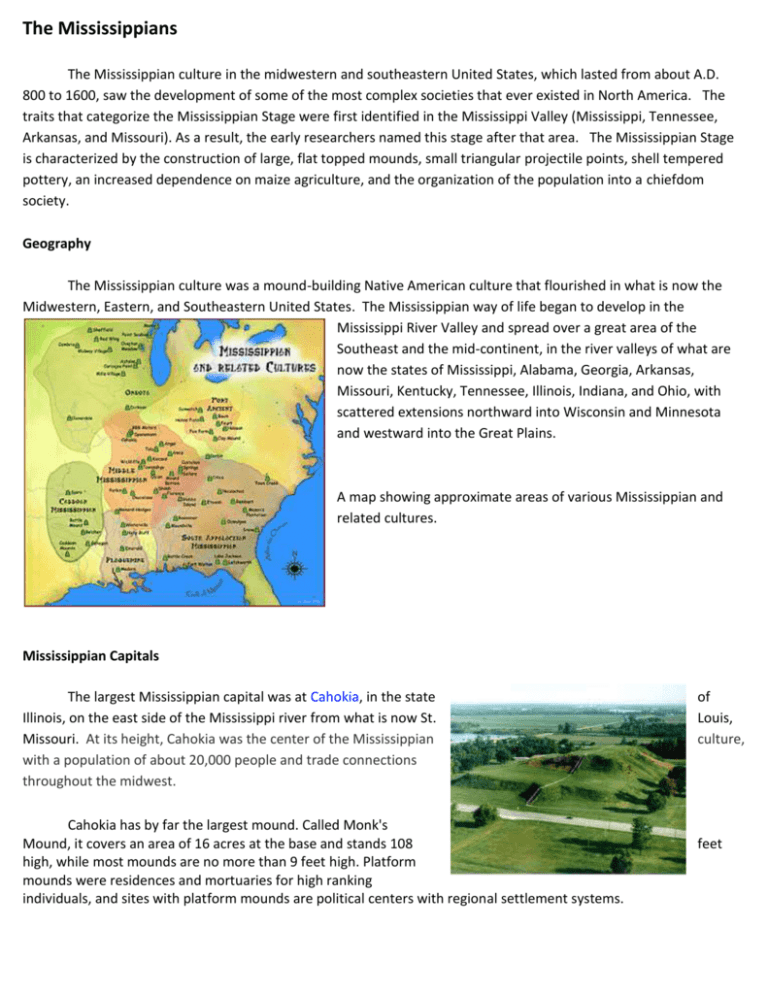

The Mississippians The Mississippian culture in the midwestern and southeastern United States, which lasted from about A.D. 800 to 1600, saw the development of some of the most complex societies that ever existed in North America. The traits that categorize the Mississippian Stage were first identified in the Mississippi Valley (Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri). As a result, the early researchers named this stage after that area. The Mississippian Stage is characterized by the construction of large, flat topped mounds, small triangular projectile points, shell tempered pottery, an increased dependence on maize agriculture, and the organization of the population into a chiefdom society. Geography The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American culture that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. The Mississippian way of life began to develop in the Mississippi River Valley and spread over a great area of the Southeast and the mid-continent, in the river valleys of what are now the states of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, with scattered extensions northward into Wisconsin and Minnesota and westward into the Great Plains. A map showing approximate areas of various Mississippian and related cultures. Mississippian Capitals The largest Mississippian capital was at Cahokia, in the state Illinois, on the east side of the Mississippi river from what is now St. Missouri. At its height, Cahokia was the center of the Mississippian with a population of about 20,000 people and trade connections throughout the midwest. Cahokia has by far the largest mound. Called Monk's Mound, it covers an area of 16 acres at the base and stands 108 high, while most mounds are no more than 9 feet high. Platform mounds were residences and mortuaries for high ranking individuals, and sites with platform mounds are political centers with regional settlement systems. of Louis, culture, feet Settlements Mississippian people, who were mainly farmers, often lived close to rivers, where periodic flooding replenished soil nutrients and kept their gardens productive. They lived in small villages and hamlets that rarely had more than a few hundred residents and in some areas also lived in single-family farms scattered across the landscape. Although there was a great deal of variation across Georgia, a typical Mississippian village consisted of a central plaza, residential zone, and defensive structures. The plaza, located in the center of the town, served as a gathering place for many purposes, from religious to social. Houses were built around the plaza and were often arranged around small courtyards that probably served the households of several related families. Some, though not all, Mississippian villages also had defensive structures. Usually these took the form of a pole wall, known as a palisade; sometimes there was a ditch immediately outside the wall. These helped to keep unwelcome people and animals from entering the village. Certain Mississippian towns featured mounds. These were made from locally quarried soils and could stand as tall as 100 feet. Most were built in stages, sometimes over the course of a century or more. Although Mississippian mounds were made in various shapes, most were rectangular to oval with a flat top. These mounds were used for a variety of purposes: as platforms for buildings, as stages for religious and social activities, and as cemeteries. Mississippian towns containing one or more mounds served as the capitals of chiefdoms. Historical and archaeological information shows that mounds were closely associated with Mississippian chiefs. Only chiefs built their houses and placed temples to their ancestors on mounds, conducted rituals from the summits of mounds, and buried their ancestors within mounds. Linguistic evidence suggests that mounds actually may have been symbols representing the earth. By using mounds as they did, Mississippian chiefs explicitly reminded their followers of their dominance over the earthly realm. Houses Unlike contemporary people, Mississippian people spent much of their lives outdoors. Their houses were used mainly as shelter from inclement weather, sleeping in cold months, and storage. These were rectangular or circular pole structures; the poles were set in individual holes or in continuous trenches. Walls were made by weaving saplings and cane around the poles, and the outer surface of the walls was sometimes covered with sun-baked clay or daub. Roofs were covered with thatch, with a small hole left in the middle to allow smoke to escape. Inside the houses the hearth dominated the center of the living space. Low benches used for sleeping and storage ringed the outer walls, while short partitions sometimes divided this outer space into compartments. By today's standards Mississippian houses were quite small, ranging from twelve feet to thirty feet on a side. Mississippian Stage The Mississippian stage is usually divided into three or more periods. Each of these periods is an arbitrary historical distinction that varies from region to region. At one site, each period may be considered to begin earlier or later, depending on the speed of adoption or development of given Mississippian traits. * Early Mississippian cultures had just transitioned from the Late Woodland period way of life (500–1000 C.E.). Different groups abandoned tribal lifeways for increasing complexity, sedentism, centralization, and agriculture. The Early Mississippian period was from c. 1000 to 1200 C.E. Production of surplus corn and attractions of the regional chiefdoms led to rapid population concentrations in major centers. * The Middle Mississippian period is often considered the high point of the Mississippian era. The expansion of the great metropolis and ceremonial complex at Cahokia, the formation of other complex chiefdoms, and the spread and development of Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC) art and symbolism are characteristic changes of this period. The Mississippian traits listed above came to be widespread throughout the region. In most places, this period is recognized as occurring c. 1200–1400 C.E. * The Late Mississippian period, usually considered from c. 1400 to European contact around 1540, is characterized by increasing warfare, political turmoil, and population movement. The population of Cahokia dispersed early in this period (1350–1400), perhaps migrating to other rising political centers. More defensive structures are often seen at sites, and sometimes a decline in mound-building and ceremonialism. Although some areas continued an essentially Middle Mississippian culture until the first significant contact with Europeans, the population of most areas had dispersed or were experiencing severe social stress by 1500. Along with the contemporary Anasazi, these cultural collapses coincide with the global climate change of the Little Ice Age. Scholars have theorized that drought and collapse of maize agriculture, together with possible deforestation and overhunting by the concentrated populations, forced them to move away. Cultural traits of the Mississippians A number of cultural traits are recognized as being characteristic of the Mississippians. Although not all Mississippian peoples practiced all of the following activities, they were distinct from their ancestors in adoption of some or all of these traits. 1. The construction of large, truncated earthwork pyramid mounds, or platform mounds. Such mounds were usually square, rectangular, or occasionally circular. Structures (domestic houses, temples, burial buildings, or other) were usually constructed atop such mounds. 2. Adoption of comparatively large-scale, intensive maize agriculture, which supported larger populations and craft specialization. 3. The adoption and use of riverine (or more rarely marine) shell-tempering agents in their ceramics. Hollow ceramic jug showing the underwater panther from the Mississippian culture, found at Rose Mound in Cross County, Arkansas, U.S., 1400-1600. height: 8 inches. 4. Widespread trade networks extending as far west as the Rockies, north to the Great Lakes, south to the Gulf of Mexico, and east to the Atlantic Ocean. 5. The development of the chiefdoms, or rule by one elite chief over several villages. Mississippian Chief Statue Georgia State Capitol Museum at Atlanta, GA. 6. The development of institutionalized social inequality. 7. A centralization of control of combined political and religious power in the hands of few or one. A Mississippian era priest holding a ceremonial flint mace as envisioned by Herb Roe. 2004 8. The beginnings of a settlement hierarchy, in which one major center (with mounds) has clear influence or control over a number of lesser communities, which may or may not possess a smaller number of mounds. The Kincaid Site in Massac Co., Illinois, showing platform mounds. Illustration by artist Herb Roe 9. The adoption of the paraphernalia of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), also called the Southern Cult. The SECC was based on the similarity of cultural items and beliefs of the Mississippian period between about AD 1000 and 1600. A regional similarity in mound construction, artifacts, ceremonies, and mythology have been found at sites throughout the American southeast; west to Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma and up into the lower Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Within this vast area, people grew maize and beans, built extensive earthworks and flat-topped pyramids (called platform mounds), and traded raw material like obsidian, copper, and gulf coast marine shells. Most interestingly, the Mississippian also shared religious notions about the world and the way it worked. Mounds One of the characteristics of Mississippian settlements is the construction of large earthen, flat-topped mounds. These were generally built by the local population toting and depositing baskets filled with dirt. The areas where the dirt came from, or was borrowed, are called borrow pits. At Moundville, these were filled with water and stocked with fish. The construction of large building projects, such as mounds, is often indicative of a powerful and influential ruling class. In the case of Mississippian Indians, this ruling class was organized as a chiefdom, in which there are two groups of people, elites and non-elites, or commoners. Organization of Society The Mississippian way of life was more than just an adaptation to the landscape—it was also a social structure. Mississippian people were organized as chiefdoms or ranked societies. Chiefdoms were a specific kind of human social organization with social ranking as a fundamental part of their structure. In ranked societies people belonged to one of two groupings, elites or commoners. Elites, who made up a relatively small percentage of chiefdom populations, had a higher social standing than commoners. This difference rested more on ideology than on such things as wealth or military power. For example, the Natchez of Louisiana, who were still organized as a chiefdom during the early 1700s, believed that their chief and his immediate family were descended from the sun, an important god to the Natchez. It was believed that the Natchez chief, probably like most Mississippian chiefs, could influence the supernatural world and therefore had the ability to ensure that important events like the rising of the sun, spring rains, and the fall harvest came on time. Because of these supernatural connections, elites received special treatment. They had larger houses and special clothing and food, and they were exempt from many of life's hard labors, like food production. The much more numerous commoners were the everyday producers of the society. They grew food, made crafts, and served as warriors and as laborers for public works projects. Elite – Chiefs, priests Commoners – farmers, craftsmen Government – Chiefdoms Very little is known (or can be known) about the form of governance in prehistoric communities. It is assumed that they were complex chiefdoms. There was certainly never anything approaching a centralized, political power structure - a Mississippian Empire. The archaeological evidence suggests regional power centers. A complex chiefdom includes a number of villages or communities under the permanent control of a paramount chief. Based on what we know of historic communities that exhibited Mississippian traits, the chief/high priest was an absolute ruler and maintained his position almost solely due to the belief system of his subjects. From the evidence of archaeology and the obviously public construction works (mounds, palisades, squares, and ball courts requiring large groups of organized laborers and the central planning they imply) we can assume that the position of the chief/high priest in Mississippian communities was an exalted one - certainly with great status and power. The political and religious centers of these chiefdoms are marked by flat topped-mounds on which were built the temples and homes of the elite. The elite were set apart from the remainder of society in other ways as well, including nearly exclusive access to an exchange network that linked the chiefs of different societies and circulated exotic items that marked and legitimized their role as leader of society. These exotic goods included among other things, copper artifacts, non-local pottery, shell ornaments, and stone palettes. The bulk of these goods have been found at the major Mississippian sites, such as Cahokia in Illinois, Moundville in Alabama, and Etowah in Georgia. Art Some of the most impressive achievements of Mississippian people are the finely crafted objects made of stone, marine shell, pottery, and native copper. Although they do not fit the Western conception of art, these items constitute a distinct artistic tradition. Using an essentially Stone Age technology, Mississippian people created gorgets (decorative collarpieces), cups, pendants, and beads made of marine shell. Many of the cups and gorgets bear elaborate decorations. By flaking, carving, and grinding stone materials, Mississippian people created large blades, elaborate eccentrics, pipes, and effigy celts. They developed copper-working techniques to create celts, small ornaments, and large copper sheets bearing decorations like those on the gorgets and cups. This technique did not involve smelting, but instead involved the cold-hammering of native copper nuggets into thin sheets that were then shaped, cut, and embossed with designs. These items belong to what is known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC). The SECC is a set of objects and symbols usually found in ritual settings or as offerings in elite graves. Rather than being art simply for the sake of art, many of these were important ritual items or parts of elite costumes. The objects themselves, or elements of their decoration, almost certainly represent supernatural beings, mythological objects, and mythical events. Their clear association with elites shows the important role elites must have played in ritual, and it also indicates how important the supernatural world was to Mississippian elites. Mississippian Vocabulary Chiefdom: Societies headed by important individuals with unusual ritual, political, or entrepreneurial skills. The societies tend to be kin-based, but is more hierarchical, with power concentrated in the hands of powerful kin leaders, who are responsible for the redistribution of resources. Chunkey: This game was played by almost all of the southeastern Indians, some variation. All of the games made use of a smooth stone disk, usually with concave sides, and two long slender poles were used. Usually only two persons played at one time, but the onlookers wagered on the game. The idea game was to start the stone disk rolling along a smooth piece of ground, after the two players threw their poles after it, with the idea of either hitting the or coming as near as possible to it, when the stone came to a rest. with of the which stone, Context: the relationship artifacts have to one another and the situation in which they are found. Adze: A tool, typically made from stone, that was presumed to be used like a modern woodworker's chisel to work wood. Canoes For Indians, the primary mode of transportation was by canoe. Canoes were made by hollowing out large trees with fire. Then the canoe was shaped with the use of stone tools, such as an adze. This canoe is currently on display at the Moundville Archaeological Park Museum. It was found in Florida. Similar canoes have been found in the Tombigbee, Alabama, Escawtaba, and Mobile Rivers and the Mobile Delta. Celts, or hoes, were used to tend gardens. They could be made of any stone, or lithic, material type, but perhaps the most impressive are made from greenstone. Many greenstone celts have been recovered from burials at Moundville without any indication that they were used to tend crops. Rather, they have been polished in such a way that archaeologists believe these celts were used more for ceremonial purposes. Photograph courtesy of the Office of Archaeological Research, University of Alabama Museums. Palettes Commonly found at Moundville and throughout the Southeast at larger Mississippian towns are stone palettes. In several contexts, these palettes have been found with traces of graphite, red ocher, and other pigments, suggesting that either they were used for mixing pigments or were painted themselves. The Rattlesnake disk is perhaps one of the more recognizable palettes and was found by a farmer while plowing his field in the vicinity of Moundville. Photograph courtesy of the University of Alabama Museums. Palisade: A walled enclosure built around a village or town, a stockade. Palisades and other structures such as residences, were constructed of wattle and daub. First, wooden posts were set into holes or trenches dug in the ground, and then cane (wattle) was weaved through the posts. Finally, the entire structure was pastered with mud (daub) on the inside and outside. Palisaded Village—the competition for ever more scarce resources compelled the tribes to fortify their villages with tree trunks set into the ground in a circular enclosure around those structures deemed most important to protect— those which stored corn and foods for over-winter survival, the chief’s dwelling and usually a sufficient number of other dwellings to provide housing for the local population—it was very rare for an entire village’s structures to be surrounded by such enclosures, called palisades. A narrow opening was usually created by overlapping the two ends of the encircling palisade. Ditches and earthworks of a protective nature were sometimes employed as well. Mound—an earthen structure or mound created by the Indians who carried baskets of earth from local sources to create a burial or ceremonial earthen mound. Mound Complexes—groups of mounds, often arranged in geometric patterns or in alignment with astronomical phenomenon, or forming groups or clusters focused upon river banks and bluffs overlooking rivers, probably served as ceremonial centers for the large populations inhabiting nearby hamlets and villages. The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (traditionally Southern Death Cult, later also as Southern Cult or Chiefly Warfare Cult) is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture that coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom social organization from 1200 CE to 1650 CE. This ceremonial complex represents a major component of the religion of the Mississippian peoples, and is one of the primary means by which their religion is understood. Sedentary – Sedentism is the term archaeologists use to describe the process of settling down to live in groups for periods of time. Horticulturalist – People who grow their food and research how to cultivate crops, increase produce, breed and engineer different kinds of crops, as well as study the biology and physiology of plants. Horticulturalists study fruits, berries, nuts, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs, and turf. Horticulturists work to improve crop yield, quality, nutritional value, and resistance to insects, diseases, and environmental stresses. Horticulture usually refers to gardening on a smaller scale, while agriculture refers to the large-scale cultivation of crops. The word horticulture comes from the Latin hortus meaning garden, and cultus, meaning to cultivate. Shell-tempered pottery – Pottery that has crushed shell added to the paste used to make the object. The shell makes the object harder and more durable. Gorgets - Gorgets are pendants that are worn on the chest, hung from a string or a necklace. Ancient Native Americans made gorgets of rare materials such as copper or marine shell, which had to be obtained through trade. Mississippian Government Very little is known (or can be known) about the form of governance in prehistoric communities. It is assumed that they were modified chiefdoms. There was certainly never anything approaching a centralized, political power structure - a Mississippian Empire. The archaeological evidence suggests regional power centers that more closely approached the Greek city-state model. Based on what we know of historic communities that exhibited Mississippian traits (principally the Natchez) the chief/high priest was an absolute ruler and maintained his position almost solely due to the belief system of his subjects. However the Natchez may not have been (and almost certainly were not) representative of the Mississippian cultural governance system everywhere and at all times. From the evidence of archaeology and the obviously public construction works (mounds, palisades, squares, and ball courts requiring large groups of organized laborers and the central planning they imply) we can assume that the position of the chief/high priest in Mississippian communities was an exalted one - certainly with much greater status and much more power to command than that wielded by chieftans in non-Mississippian cultures encountered by Europeans at time of first contact. Mississippian Religion The Mississippians were a culture of sun worshipers - or rather people who worshiped the all-powerful, allknowing deity ruling the universe for whom the sun was the physical manifestation. Fire, because of its light and heat, was also symbolic of the sun on earth and a perpetual sacred fire was kept in nearly every village of any size. This fire was extinguished once a year and a new one kindled as part of a thanksgiving celebration at the time of the first corn harvest. This sacred fire - and particularly maintaining its ritual purity - was a central religious feature in village life throughout the year. If the sacred fire was extinguished for any reason, or became ritually polluted, it was a cause for great concern since without the protection of the fire the community was laid open to disaster. In their central cities dwelt the sun's representative on earth referred to by the Natchez as the Great Sun. This person was part chieftan and part high priest and always dwelt, with his attendants, in a large house on top of an earthen mound. He performed ritual duties and led the people in ritual activities during festivals and ceremonies. The Great Sun's position was entirely dependent on his mother's status since (like Egyptian pharoahs) power descended through the female line. Mississippian Economy Agriculture Life revolved around farming and agriculture - a task performed almost exclusively by the women - and was supplemented by hunting, fishing and gathering - almost exclusively performed by the men. Corn was the chief crop of Mississippian communities but they cultivated a wide variety of other plants as well - squash, sunflowers, goosefoot, maygrass, sumpweed, amaranth, knotweed and others. Beans appear to be a late addition to the Mississippian agricultural communities appearing only a century of two before the arrival of the Europeans. Agricultural production was supplemented by gathering wild foods - nuts, berries and other fruit - as well as hunting, with deer, turkey, fish, shellfish, and turtles making up the majority of animal protein consumed. Mississippians grew much of their food in small gardens using simple tools like stone axes, digging sticks, and fire. Their fields looked quite different than those we see today. They were not divided by crops as ours are today. Instead, beans, corn, squash, and other crops grew alongside of one another. This was an efficient use of land because the corn stalks provided shade for the lower crops and acted as supports, or stakes, for the beans to wind around. Trade The Mississippians also engaged in extensive trading activities obtaining obsidian from the Yellowstone area, copper from the Lake Superior region, mica from the Alleghenies, and shells from the Gulf coast - all areas outside their principal sphere of influence. From what we can discern at this late date these items were used principally for the manufacture of ritual and status items for high caste individuals rather than being integrated into the general economy. Conch shell (Busycon) dipper, unknown source. Marine shell, such as the example illustrated here, and a variety of other materials were obtained from distant locations through trade. The city of Cahokia was a Mississippian marketplace where one might obtain marine shell, different types of stone for making arrowpoints or woodworking tools, or finished goods like Mill Creek chert hoes from Union County, Illinois. In the marketplace, one might have exchanged white-tailed deer hides or beaver pelts for marine shell or another exotic good. Mississippians made cups, gorgets, beads, and other ornaments of marine shell such as whelks found in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. By this time, Native Americans had been involved in long- distance trade for at least 3,000 years, and Mississippian people continued to exchange material and objects with distant communities. For example, Mississippians living along Mill Creek in Union County used high-quality stone found along the creek to make hoes for farming. These hoes were traded throughout Illinois and the Midwest. Birger figurine, BBB Motor site, Madison County. They used Missouri flint clay to make large pipes and statues. This soft stone could be carved and finished with harder stones. In this image, we see a woman with a hoe in her hand kneeling over the back of a serpent. Like their Archaic and Woodland ancestors, Mississippian people continued to acquire copper from the Great Lakes region. They pounded copper nuggets into flat sheets. In this example, a thin sheet of copper with an embossed sun symbol was applied onto an earspool. Copper-covered earspool, Greene Co. Engraved Mississippian bean pot, Frazier site, Fulton County. Abstract symbols such as the ones illustrated here adorned many objects including pottery jars and marine shell. This pot was also decorated with a red slip, a mixture of liquid clay and an iron-rich pigment, which was painted on the exterior of the vessel. Archaeologists also have found evidence that ideas, often in the form of specific designs found on pottery or engraved into marine shell, were widely distributed during Mississippian times. Abstract images of forked eyes, hand and eye motifs, birds of prey, sun symbols, and the circle and cross are found throughout the country east of the Mississippi River and west to the Spiro site in Oklahoma. Mississippian trade involved much more than material and objects. It appears that ideas were also widely exchanged. Mississippian Period Warfare There appears also to have been an element of ritualized warfare. In Mississippian times this may have been performed by a special warrior caste. The exact role warfare played in Mississippian life is unknown and still under active investigation and evaluation. Warfare affected the lives of Indians in many significant ways. Indian men considered themselves warriors and trained to use the bow and warclub. Valor in battle, demonstrated through the killing of enemies, was a primary means of social advancement as recently as the nineteenth century. Warfare also became a prominent theme in the Indians' belief systems and greatly affected the development and organization of their societies. Significant warfare first began to develop among Indians in the Mississippian Period (A.D. 800-1600), a time when relatively large societies called chiefdoms evolved throughout southeastern North America. During this period defensive fortifications were first built around some towns. These included log palisades that completely encircled large towns such as the one at the Etowah Mounds in north Georgia. Palisades were often plastered with clay to keep them from being ignited by burning arrows. Sometimes they incorporated defensive towers (bastions) that allowed archers to shoot at enemies who got close to the wall. Ditches similar to moats were also dug around some palisades and were part of the fortifications of both the Etowah site and the Ocmulgee site at Macon. Warriors honed their archery and war club skills through lifelong training. According to early historical accounts, they demonstrated impressive skill in using war clubs and were favorably compared to European fencing masters. The warriors also played a lacrosse-type sport called "the ball game" in which they employed war club–sized ball sticks reminiscent of combat with war clubs. The most common type of warfare was a raid carried out by a small group of men; a raiding party would surreptitiously enter an enemy chiefdom's territory to attack unsuspecting households or ambush people. Warriors typically used war clubs in these raids. Trophies from the victims, such as scalps, were taken to prove their success in the encounter. In many Indian cultures the killing of one's kinsman by an enemy necessitated reprisal. This could result in long-term, chronic raiding between enemy chiefdoms as each side in turn sought revenge on the other. Historical accounts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries also describe a few large-scale battles between the armies of enemy chiefdoms. Each army consisted of a few hundred men arranged in a formation, with the chief acting as overall commander. They would shoot their arrows at one another until the supply was expended; then they would engage in hand-to-hand combat with war clubs. Weapons Bows and arrows were widely used in Indian warfare beginning in the Late Woodland or Early Mississippian Period. Warriors used a thick D-shaped simple bow made from hickory, ash, or black locust that was fifty to sixty inches in length and had a pull weight of about fifty pounds. These bows could send arrows long distances and were typically used to shoot at enemy villages or units of warriors at a distance. Natchez Indian Warrior War clubs also came into significant use during the Mississippian Period. They were carved from a hardwood such as hickory and were usually about one-and-a-half to two feet long, although some may have reached three feet in length. There were several types, the most common form being the atassa, which was actually a wooden sword shaped like a pirate's cutlass. Other common types were the globe-headed club, which had a three-inch spherical knob at the end of a slightly curved handle, and the tomahawk, a stone axe head attached to a wooden handle. Indian War Clubs War clubs were the preferred combat weapon because Indian warriors could raise their social status by killing enemies in single combat. They were widely depicted in Mississippian Period art in association with images and symbols of warfare. In historic Creek and Cherokee myths they were associated with the Lightning or Thunder deity, sometimes in the form of a falcon. Chiefs and warriors possessed ceremonial forms of war clubs that incorporated symbols of the Sun and Thunder deities and served as markers of their ceremonial status. These were made entirely from stone that had been chipped or ground into the desired shape, or alternatively, were tomahawks that had copper heads affixed to wooden handles. Indian War clubs Mississippian Symbols Our grasp of Mississippian symbolism is only rudimentary. A culture as rich, vibrant and diverse as the Mississippians no doubt had an iconography equally rich and vibrant. Since we do not know the myths and stories attached to these symbols we can only view them "through a glass darkly". What their true meanings were and the emotions and devotion they elicited from those who held them sacred can never really be known. The meanings attached to the following symbols are the best guesses we can make based on the frequency of their occurrence in the archaeological record and their current use and interpretation by contemporary tribes that are presumed to descend from the Mississippian tradition. Cross-in-Circle The trademark symbol for Mississippian culture is the cross enclosed by a circle since it is encountered at every Mississippian site excavated. This symbol apparently reflected the Mississippian's world view of the division of the earth into quarters. It was also used as a symbol of the all powerful Sun as well as the sacred fire (a reflection of the sun). The Hawk Man Among the Mississippians it was the hawk (rather than the eagle) that was considered the messenger of the gods. Their art has numerous representations of the sharp-breasted hawk and/or hawk man. Among historic tribes these sharp-breasted hawks were sky spirits who used their razor- like breasts as weapons. As creatures of the sky they were in constant warfare with the spirits of the underworld. The Horned* Rattlesnake (Feathered Serpent) Rattlesnakes were/are sacred animals among historic tribes that are presumed to descend from Mississippian cultures. The art of the Mississippians are filled with numerous depictions of horned (and sometimes winged) creatures with the bodies of rattlesnakes and the antlered heads of panthers. These "water panthers" were creatures of the underworld and were locked in a perpetual war with the creatures of the sky. Their battles were responsible for thunderstorms, tornadoes and earthquakes. The horned serpents were also Masters of the Rain and gifts of tobacco and food were sometimes given them to induce rain for parched crops. * - Antlers and horns signified spiritual power, especially when applied to animals that didn't ordinarily have them birds, snakes, humans, etc. The Weeping Eye The Weeping Eye (aka Hawk Eye) was another presumed symbol of deity. While it was a common motif in Mississippian art its precise attributes are less well defined than many of the other symbols in use by this culture. The Hand and Eye The Hand and Eye motif - a human hand with an eye gazing out from the palm - was yet another symbol of deity. It was one of the most common motifs in Mississippian symbology and rock art but like the Weeping Eye its exact meaning is obscure. The Bilobed Arrow The Bilobed Arrow is often seen in the headdresses of the Hawk Men although it's meaning is obscure. It is presumed to have something to do with warfare and battle and is (according to Howard) a stylized representation of the atlatl - a weapon formerly in wide use until superceded by the bow and arrow. Mythology The mythology of the Mississippians was based on their view of the earth as a visible sacred landscape that reflected the unseen spiritual one. The earth was alive with spiritual forces - both good and bad - that had to be propitiated and acknowledged. It was the duty of humanity to bring itself into line with, and intercede in, the spirit world so that the many warring and discordant elements of the cosmos could be brought into harmony thereby bringing about order, stability and peace. The Mississippians lived in a three tiered universe since they (as far as we can tell) divided their universe vertically into three sections: An underworld ruled by spirit snakes who had command over the waters and who dwelt in deep pools in rivers. When unhappy or affronted they caused floods and tipped over canoes full of travelers.... An upper world ruled by spirit birds who commanded the winds and the clouds. They lived in the far west and on occasion carried a human off for some unknown purpose... And a world between these two - the earth which itself was divided into four parts that corresponded with their four cardinal directions. It was humanity's unfortunate fate to be caught between these frequently squabbling spiritual superpowers The powerful spirit beings who ruled the Upper and Lower Worlds were often unhappy with each other and since each possessed prickly egos and were easily offended they were constantly at war with each other. Their battles resulted in crop flattening windstorms, thunderstorms, tornadoes, hail and floods. It was the duty of humans, by intervening and communicating with these beings, to effect a kind of truce and keep everybody happy. While it's impossible to know the mythologies of non-literate and prehistoric cultures, archaeologists and anthropologists believe they can approach the reconstruction of some myths based on traditions preserved by historic tribes in the region formerly occupied by the Mississippians. Based on common artistic conventions and motifs discovered archaeologically that are identifiable elements of stories and myths passed down by historic tribes the bare outlines of certain myths can be deduced. The story outline below - while common to many different tribes and cultures - is believed to be a survival of a Mississippian legend: Spider Steals Fire At one time humans living on earth had no fire because it was jealously guarded by Others who would not share. The people and the animals held council to procure it and it was agreed that someone should go steal it. Each time the call for a volunteer to do this went out - the Spider volunteered first - but was ignored. Several Animals of various sorts (with greater status or strength or cleverness) were chosen over Spider. They attempted to steal fire from the Others but the fire always burned them and they failed. At last Spider was allowed to go. It spun a basket of silk which it slung on its back, placed a piece of fire in it and returned successfully to the council where the first fire was kindled. http://www.naturealmanac.com/fixtures/sidebars/mississippians.html#who